This article first appeared in the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL, volume 38, number 03 (2015). The full text of this article in PDF format can be obtained by clicking here. For further information or to subscribe to the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL go to: http://www.equip.org/christian-research-journal/

Connoisseurs of human nature will be quick to identify the manifold behavioral extremes of their fellow men. Once the boundary from moderate to extreme is crossed, social propriety is thrown to the wind, and any imaginable absurdity is made possible. Skiing, for example, is a rather normal winter sport. But skiing off a cliff in an avalanche-prone region is rightly labeled an “extreme” sport. Bathing is an expected part of modern hygiene—only insofar as it doesn’t involve the “extreme” of throwing oneself into a freezing lake for the sheer exhilaration of it. Chocolate ice cream is good, but double the chocolate, and it can be marketed as “extreme.”

Extremism, however, refers to much more than velocity and flavor. The mere mention of extremism rightly evokes images of ideologically motivated shootings, beheadings, and bombings, along with destructive governmental policies.1 Those caught in the middle find themselves living in fear of the extremes.2 To be labeled “extreme” is to be alienated to the fringe—the wasteland of violent and feral outcasts.

Myriad recent books and articles, both popular and academic, have defined and delineated the horrors of so-called “extremism.”3 The word is so regularly employed in the media that its connotations are well ingrained in the Western consciousness. A quick glance at Merriam-Webster divulges the meaning of the “extreme” as a reference to the greatest possible extent—that which exceeds the ordinary. The extreme is the last, the end, and a very high degree. When applied to the world of ideas, a philosophical position may be taken to its logical conclusion, that is, the farthest extreme to which it can be realized while still retaining its internal coherency. Yet, for all its lexical richness, the word extreme says very little until it is coupled with an ideology, philosophy of life, or religious view—that is, right wing extremism, Islamic extremism, and so on.

The extreme devotion of a parent toward her child will be characterized by love and self-sacrifice, whereas extreme devotion to Marxist political policies may likely result in violence and suppression.4 Likewise, a schoolteacher shows little moderation or equability when he insists on the fact of the Earth’s solar orbit over and against the fixed Earth view. He might be labeled an extremist for insisting on his belief in such an unbudging way and to such a high degree. But this is hardly a bad thing.

Though devoted parents and diligent teachers would hardly be considered extremists by the majority, these examples reveal that extremism is itself an ambiguous title until it is attached to an ideology. But since extremism is rarely detached from the political or philosophical outlooks it qualifies, criteria are necessary for a proper evaluation of the merit or demerit of extreme belief or behavior. These criteria will help demonstrate that perhaps “extremism” itself is less a problem than we might think.

EXAMINING ORIGINS

A proper evaluation of any extremism must begin with the historical and philosophical origins of the adjective that precedes it, be it environmental, Christian, feminist, Islamic, Hindu, or the like. Since extremism is only as shocking as the worldview to which it is attached, the initial question must examine the source of the ideology under investigation.

In taking the example of feminist extremism, the question must be posed as to what kind of feminism is being evaluated. Are we referring to an exiguous current found within another worldview; are we speaking of the militant ideology that grew out of twentieth-century continental philosophy; or are we referring to something else entirely? Moreover, who were the major players in founding the movement? What are the philosophical assumption of its founders and principal representatives?

The same applies to religious extremism. With so much talk of Islamic extremism, especially following 9/11, it is worth asking about the origins of Islam and how this relates to current extreme applications of Islamic devotion. Who was this Muhammad who founded Islam? What beliefs and behaviors characterized his life? When Muhammad lived his philosophy of life to its greatest possible extent—to its logical conclusion—what form did his religion take? Similar questions are valuable when considering the origins of any worldview.

EXAMINING CONTENT

The origins of a belief, however, will reveal only so much. Evaluating the content of the worldview is of utmost importance. Understanding the philosophical foundations of a worldview is key to knowing what those foundations will look like when they are taken to their extreme. If self-sacrificial love is at the heart of a belief system, then its extreme form will look much different from a belief system that centers on territorial conquest or sociopolitical control.

Take Buddhism for example. The foundation of Buddhist thought centers around the Four Noble Truths, which state that life is full of suffering (dukkha), that there is an origin to our suffering (samudaya), that suffering can be ceased (nirodha), and that this cessation of suffering (marga) can be achieved by following the Noble Eightfold Path, which focuses on certain observances.5 Though praxis varies within the numerous Buddhist strains, the exercise of meditation as an escape from the physical world of suffering is central to understanding the Four Noble Truths.

If these core Buddhist teachings are then taken to the extreme, what will this look like? A thorough response is more complex than can be elucidated here, but if the life and teaching of Siddhartha Gautama, the founder of Buddhism, is to be imitated to its greatest possible extent, Buddhist extremism, at best, would require complete emotional and intellectual withdrawal from the world with all of its cares.6 An extremism of this kind, though largely innocuous, would offer little in the way of scientific or artistic advancement, nor would it contribute to the social or economic wellbeing of the larger community.

EXAMINING INCENTIVES

Further evaluation of a worldview in its extreme form requires an examination of the incentives it offers its adherents. In the same way an athlete is driven forward by his love for the game or his desire to win, religion adherents and political activists are driven by various incentives. For example, obedience to God and hope of eternal recompense is the motivational propeller that is thought to drive Islamic terrorism forward.

Every philosophical outlook or religious position will offer some reason for commitment. Self-satisfaction, internal peace, heavenly reward, fear of hell, threat of punishment, monetary gain, health, security, strength, dominance—all of these can be used to motivate. And while these incentives may not be wrong in and of themselves, worldviews that demand significant accomplishments or regimented application in exchange for either divine or earthly compensation can tend toward violence or other extreme practices, such as self-flagellation. That which drives a worldview forward—be it love or hate, goodwill or oppression—is significant to predicting how extremism will be applied in that worldview.

EXAMINING RESULTS

The driving impetus of a worldview is closely related to its proposed results. Understanding the ultimate goal of a religion will clarify what an “extremist” hopes to accomplish by his extremism. One of the intended results of Hitler’s Nazism was to purge the Aryan race of perceived human contaminants, making the extreme application of Nazism a genocidal horror. On an individual level Nazi extremism would have meant complete devotion to the Nazi project. On the contrary, an intended result of Christianity is the conversion and baptism of the nations (Matt. 28:18–20). On an individual level, this is achieved by repentance and genuine faith in Christ (Rom. 10:9).

What then is the intended result? Where does a particular worldview ultimately take us? What does it want—a church on every street corner? A minaret dominating the skyline of every city? The eradication of international borders? The destruction of a certain ethnicity? The repression of religion? The abolition of all moral restraint? Extremists may be nothing more than those who know what they want and who are devoted to making it happen in one way or another.

EXAMINING LIMITATIONS

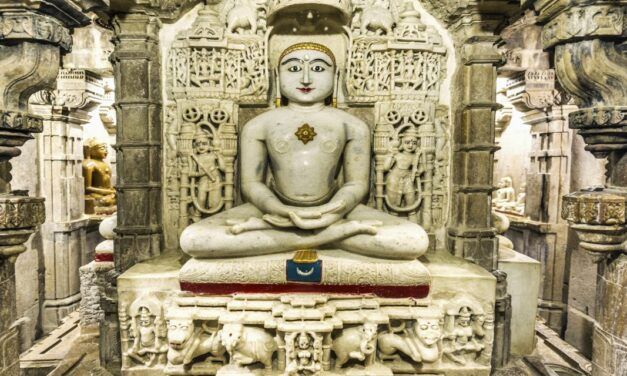

While extremism refers to the greatest, farthest, and most, a worldview may put limits on how its objectives can be obtained. Certain restrictions may quash violence or oppression even when a worldview is taken to its logical conclusion or practiced to the greatest possible extent. A passionate evangelist, whose proclamation of the gospel is driven by a desire to obey Christ, is not consistent with Scripture if he uses coercion and violence to make converts. Faithful application of the gospel of grace by faith simply does not allow for such behavior. A Jainist, who lives by the principle that no living thing should be harmed, may go to “extremes” in protecting life by ensuring the preservation of creatures with which he comes in contact. He is, however, under strict obligation to refrain from violence.

While some religions deem violence a necessary requisite to devotion,7 many theistic religions that rely on either divine revelation or highly developed systems of tradition often contain moral codes that are intended to limit certain behaviors among devotees. Such religions often issue lists of dos and don’ts that are not to be bypassed.

Secular philosophies also contain moral applications that ensue logically from their metaphysics, restricting the extremes to which the philosophy might be taken. Unlike theistic traditions, however, secular philosophies lack the “divine authority” of scriptures, making them more easily prone to moral open-endedness. The moral limitations put on secular philosophy in its extreme forms are only as good as the best argument given or the prevailing consensus of the community at any given moment. This is not to say that secular philosophies are more disposed to violent extremism. All it means is that the limitations a worldview places on its “extreme” application must be examined carefully before that worldview is falsely accused of violence.

EXTREMISM AND CHRISTIANITY

Christians believe that their religion originates with the Triune God, revealed in Scripture and in the person of Jesus Christ. They believe that the cross of Christ is central to human history and salvation. Their call and objective is to love the Lord with all their heart, soul, mind, and strength, and to love their neighbor as themselves (Mark 12:30–31). Christ demands everything of His followers, asking that they take up their cross and lay down their lives (Matt. 16:24). Christ demands that Christian love be taken to its logical conclusion, and that Christian commitment exceeds the ordinary.

Some, however, are reluctant to embrace the extreme to which Christ called His church. The editor of a popular Christian publication recently argued that “the world desperately needs an energetic renewal of intelligent moderation in politics and in religion.”8 But this is hardly the way of truth. Thinking such as this is a fearful reaction to a world where a plurality of religions and philosophies vie for dominance. Thinking such as this demands that people go on half-heartedly, careful not to believe anything too strongly. And while there is a place for moderation, it is difficult to imagine how Christ would want moderate faith, moderate obedience, moderate devotion, or moderate defense of truth. Religious moderation demands that Christian theologians and philosophers refrain from thinking too hard. Moderation is a call to disengagement—to abandon truth for the false security of interreligious accord. Moderation of belief requires that Christians live for Christ only insofar as not to ruffle the delicate feathers of the politically correct media and not to upset the extreme tolerance of the self-proclaimed intelligentsia who are often against extremism to the extreme.

Extremism itself may not be the problem. The real problem is the worldview to which extremism attaches itself. We should not be surprised when people take their worldviews seriously and live them out to their logical conclusions. We should not be surprised when a religious view is believed to the greatest possible extent, and when a practice is lived out to the very end. When ultimate reality, truth, and eternity are on the line, moderation of commitment and belief is of no value. The shocking solution to our world’s many problems may not be moderation, but attachment to the right kind of extreme.

Jonah Haddad has an MA in philosophy of religion from Denver Seminary and is the author of Insanity: God and the Theory of Knowledge (Wipf and Stock, 2013). He is involved in apologetics ministry in France.

NOTES

- See, e.g., Dan Bilefsky and Maïa de la Baume, “Terrorists Strike Charlie Hebdo Newspaper in Paris, Leaving 12 Dead,” New York Times, Jan. 7, 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/ 2015/01/08/world/europe/charlie-hebdo-paris-shooting.html; and Shreeya Sinha, comp., “Ottawa Shooting Is Latest in Growing Number of Attacks Linked to Extremism,” New York Times, Oct. 23, 2014, http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/24/world/americas/in-the-west-a-growing-list-of-attacks-linked-to-extremism.html, which compiles a list describing recent attacks carried out in the name of Islam.

- Both the political right and left have used the label of extremism to ostracize and defame their opponents. See Norm Ornstein, “When Extremism Goes Mainstream,” The Atlantic, July 23, 2014, http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2014/07/when-extremism-goes- mainstream/374955/.

- For an example, see Reza Aslan’s Beyond Fundamentalism: Confronting Religious Extremism in an Age of Globalization (New York: Random House, 2010).

- For more on the horrors of the application of Marxist philosophy, see Jean-Louis Panné et al., The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression, trans. Mark Kramer and Jonathan Murphy (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1999).

- Thich Nhat Hanh, The Heart of the Buddha’s Teaching: Transforming Suffering into Peace, Joy, and Liberation (New York: Broadway, 1999), 9–11.

- Winfried Corduan, Neighboring Faiths: A Christian Introduction to World Religions (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1998), 222–23.

- See, Kali worship in Hinduism, Corduan, Neighboring Faiths, 207.

- John M. Buchanan, “Moderate Wisdom,” The Christian Century 131, 17 (2014), 3.