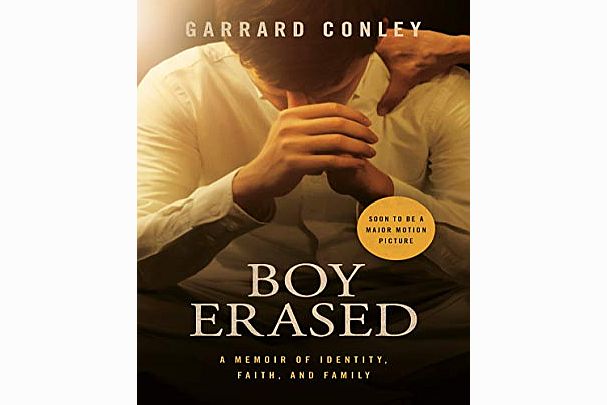

A book review of

Boy Erased: A Memoir

by Joe Dallas

(Riverhead Books, 2019)

This is an online review from the Christian Research Journal. For The full text of this article in PDF format can be obtained by clicking here. For further information or to subscribe to the Christian Research Journal please click here.

The personal narrative is today’s tool of persuasion, the best stories winning debates over more reasoned but less artful arguments. With that in mind, I closed Garrard Conley’s memoir and said aloud, “He’ll win.”

Boy Erased (Riverhead Books 2016) is painfully enjoyable — painful in that it chronicles a young man’s trajectory from faith to confusion to rebellion. Enjoyable, though, in that Conley is an exceptional writer; a poet autobiographer whose book, is a thoroughly engaging read.

Yet for Christian readers, it should be seen as an unverified account of a ministry experience which, if true, is a cautionary tale describing what not to do when someone says, “I’m Christian. I think I’m gay; so now what?” Whether substantially accurate or embellished, it will no doubt be used as a weapon against all ministries efforts to help same-sex attracted people lead godly lives.

Full disclosure: I was associated professionally with the organization Conley writes in detail about, the Memphis-based Love in Action (LIA) program, when I served as president of Exodus International (a coalition of ministries that both LIA and I were a part of).

I find myself commiserating with Conley over his experiences while disagreeing with his conclusions. His experiences are especially informative to Christian readers who want to better understand the struggles of those growing up in church, sincere in their faith, but experience sexual feelings they never chose.

He was raised in a devout Baptist home by parents he describes affectionately, even when detailing their imperfections, especially his father’s. When as a young man he confesses his homosexual yearnings to them, they respond by insisting he get help.

That began his participation in the LIA program, a participation marked by ambivalence from the beginning. “God, I don’t know who You are anymore, but please give me the wisdom to survive this,” he prays as he enters the program. The fact that it was viewed as something to survive, and that God was viewed as Someone Unknown, tips the reader off that shades of gray will dominate these pages.

What emerges in black and white, though, are examples of errors. Conley’s are easy to spot, especially his final and enduring one. But it’s more instructive to review the errors of others in his story, as Christian families and minsters repeat them often.

Conley was coerced — the first of many serious wrongs. With the best of intentions, his parents thought pressuring their son into a program would move him away from homosexual sin and toward holiness. On the contrary, it set him up for a me-versus-them mentality, which permeates the book. While he never writes about his parents as enemies, he clearly feels pushed into a sanctification he didn’t feel personally motivated to pursue. Parents should learn from this that taking a position with your adult son or daughter is right, but seeking to push them into that position is counterproductive and damaging.

The ministry’s insistence (per Conley’s account) that homosexuality constituted addiction was another wrong. A common error has been to treat homosexual desire as one treats alcoholism but, as Conley’s case attests, he was not addicted to sex with men; he was simply attracted to them. They’d have served him better by helping him manage sexual temptations when they arose, understand them from a biblical perspective, and feel no shame in being tempted, as that is part and parcel of the believer’s experience.

A biblical perspective, for example, would have emphasized the fact that homosexuality is, like a number of other sexual sins, condemned in both Testaments (Lev. 18:22 and 20:13; Rom. 1:26–27; 1 Cor. 6:9–10; 1 Tim. 1:9–10). Yet the Bible promises deliverance from the power of sin (Rom. 6:14), strength to resist the pull toward sin (1 Cor. 10:13), and transformation of the total person (2 Cor. 3:18). Any biblically sound ministry dealing with sexuality should emphasize this.

Finally, in a part of the story that will be replayed ad infinitum by people wishing to discredit all ministries like LIA, Conley is commanded to admit, in a group setting, how angry he is at his dad. This stems from the notion that male homosexuality indicates a father–son problem, an idea applicable to many; inapplicable to many, as well. It’s an error to insist that any one theory on the origins of homosexuality will hold true in all cases, and a virtue to adhere to the biblical explanation of our sin nature as the final explanation.

Boy Erased draws a portrait of a loving, imperfect family struggling to respond to a difficult problem, which is commendable. What’s lamentable, though, is the fact it also draws, however artfully, the unbiblical and the oh-so-wrong conclusions. ––Joe Dallas