This article first appeared in the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL, volume 35, number 06 (2012). The full text of this article in PDF format can be obtained by clicking here. For further information or to subscribe to the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL go to: http://www.equip.org/christian-research-journal/

SYNOPSIS

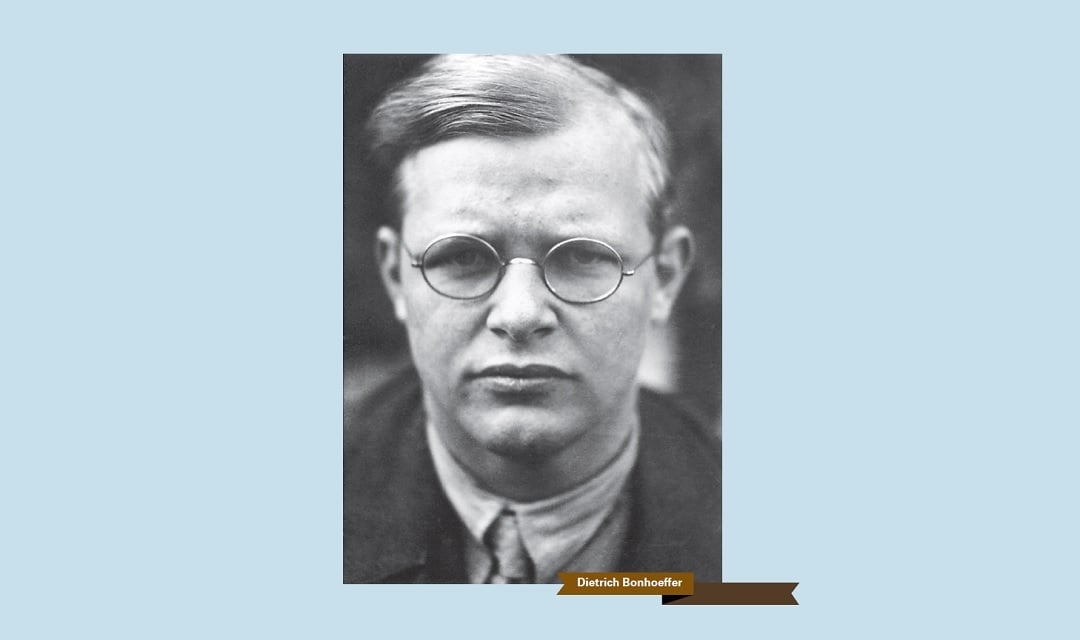

Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s theology seems to appeal to just about everyone. After reading The Cost of Discipleship, I was excited by Bonhoeffer, but my zeal for him waned after reading Letters and Papers from Prison. I discovered later that Bonhoeffer’s theology was different from my evangelical views. Most evangelicals appreciate Bonhoeffer’s stress on the importance of Scripture that led him to meditate daily on it. However, during the last few years of his life, Bonhoeffer discontinued his daily Bible meditation, opposing the practice as too “religious.” Bonhoeffer did not believe in biblical inerrancy, but followed Karl Barth’s view that Scripture is true, even if it is not empirically accurate. Because of this, he rejected apologetics, considering it a category mistake. Under the influence of Nietzsche, he also denied that Scripture contains any universal, timeless principles or propositions.

Bonhoeffer’s view of salvation was also quite different from the views of most evangelicals. Though he experienced some kind of conversion around 1931, he hardly ever mentioned it. Later he expressed distaste for Christians talking or writing about their conversions. He even stated that the gospel was not primarily about individual salvation. While in prison, he preferred the Old Testament to the New Testament. He complained that the New Testament was tainted by “redemption myths,” but he liked the this-worldliness of the Old Testament. Besides all this, Bonhoeffer was a universalist. In sum, Bonhoeffer’s theology was neo-orthodox, and his position was even more liberal than Barth’s.

When President George W. Bush ordered the invasion of Iraq, he invoked Dietrich Bonhoeffer to help justify his action. Some Bonhoeffer scholars were indignant, arguing that Bonhoeffer would have decisively opposed the “war on terror.”1 In 1966 Joseph Fletcher honored Bonhoeffer as a key inspiration for his book Situation Ethics; he argued that situation ethics meant that (among other things) abortion was permissible in some situations.2 The Presbyterian minister Paul Hill, on the other hand, murdered an abortionist in Florida in 1994, claiming that his violence was the same as Bonhoeffer’s resistance to the Nazi regime.3 In the 1960s, radical death-of-God theologians claimed that they were building on Bonhoeffer’s insights in Letters and Papers from Prison, but a couple of years ago the evangelical biographer Eric Metaxas told Christianity Today that Bonhoeffer was as orthodox as Saint Paul.4 Bonhoeffer seems to have become all things to all men, beloved by all, everybody’s saint.

But how can Bonhoeffer appeal to so many contradictory constituencies? One Bonhoeffer scholar, Stephen Haynes, has devoted an entire book to dissecting the many conflicting interpretations of Bonhoeffer. Indeed, Haynes’s own interpretation of Bonhoeffer changed as his theological convictions shifted. As a young man, Haynes identified with evangelicalism and considered Bonhoeffer a fellow evangelical. However, as Haynes became more liberal in his theological views, he discovered that Bonhoeffer was a fellow liberal. At all times, it seems, he was a fan of Bonhoeffer’s, despite the changes in his own theological perspective.5

MY ENCOUNTER WITH BONHOEFFER

As an undergraduate in the late 1970s, I (like many other evangelicals) first encountered Bonhoeffer by reading The Cost of Discipleship. Brimming with admiration for this theologian who sacrificed his life to oppose the evils of Nazism, I enthusiastically recommended his book to my friends. Bonhoeffer’s understanding of radical discipleship and self-denial resonated with me. I also esteemed him for rejecting racism and anti-Semitism, and for his works of compassion for the poor and oppressed. Bonhoeffer was my hero.

Several years later I read Bonhoeffer’s Letters and Papers from Prison, expecting spiritual nourishment. However, it baffled me. Was this the same Bonhoeffer I knew and loved? Had he changed? What did he mean that we have to live “as if there were no God”? Why did he castigate Rudolf Bultmann’s opponents?6 Since Bultmann rejected miraculous events in Scripture, I opposed Bultmann. Bonhoeffer apparently did not share my concerns.

My next exposure to Bonhoeffer came in the late 1980s, when I was working on my Ph.D. in modern European history. In a church history course at a liberal seminary both the textbook and professor admired Bonhoeffer, considering him a fellow liberal. It struck me forcefully that Bonhoeffer was praised by just about everyone across the theological spectrum, from fundamentalists to evangelicals to neo-orthodox to liberals to death-of-God theologians, not only for his courageous life, but also for his theology. How could this be?

Divergent Discipleship

I decided to find out, so I began a systematic study of Bonhoeffer that led me to some rather unsettling discoveries.7 I found that Bonhoeffer’s views about Scripture, salvation, and other crucial doctrines were quite divergent from my evangelical beliefs. Bonhoeffer was not the theological conservative I had earlier assumed him to be.

Why, if what I am saying is true, have many evangelicals embraced Bonhoeffer so uncritically? First, most evangelicals read The Cost of Discipleship and maybe Life Together, works where Bonhoeffer’s theological problems are not so obvious. Second, Bonhoeffer was a courageous individual who uniquely combined a powerful intellect with compassion for the disadvantaged. Third, most evangelicals do not understand Bonhoeffer’s intellectual context. He was a sophisticated thinker completely conversant in—and heavily influenced by—Continental philosophy, including Kant, Hegel, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Heidegger, and others. Fourth, many evangelicals applaud Bonhoeffer for rejecting liberal theology, not realizing that the neo-orthodox theology he embraced is still far from evangelical theology. Even if it rejects nineteenth-century-style liberal theology, neo-orthodox theology is on the liberal side of the theological spectrum, since it rejects biblical inerrancy and other doctrines central to genuine Christianity.

BONHOEFFER’S ATTITUDE TOWARD SCRIPTURE

Probably nothing about Bonhoeffer appeals to evangelicals more than his insistence on the authority of Scripture. He professed, “I believe that the Bible alone is the answer to all our questions and that we need only to ask insistently and with some humility for us to receive the answer from it.”8 This message appears in many of his writings, especially Life Together, where he encouraged Christians to integrate meditation on Scripture into their daily lives.

Bonhoeffer’s doctrine of Scripture did not change appreciably during his career, but his attitude toward Scripture did fluctuate. Sometime around 1931, Bonhoeffer had a significant religious experience, which some describe as a conversion experience. Bonhoeffer rarely mentioned this experience, but in a private letter he testified, “For the first time I discovered the Bible.”9 Afterward, Bonhoeffer meditated daily on Scripture and insisted that his theology students do likewise. Many evangelicals wrongly conclude that Bonhoeffer was urging all Christians to follow this example. However, Bonhoeffer was directing his exhortations primarily to theologians, not to the laity. In Ethics he explicitly stated this: “Scripture belongs essentially to the preaching office, but preaching belongs to the congregation. Scripture must be interpreted and preached. In its essence it is not a book of edification for the congregation.”10 This is a startling statement by a Lutheran theologian, since it flies in the face of Luther’s insistence on the priesthood of all believers.

Struggles with Scripture

After 1939 or so, Bonhoeffer seems to have lost his earlier zeal for the Bible. In January 1941, June 1942, and March 1944, he admitted to his friend and confidant Eberhard Bethge that he went days and weeks without reading the Bible much, though sometimes he would read it voraciously.11 He wrote, “I am astonished that I live and can live for days without the Bible— I would not consider it obedience, but auto-suggestion, if I would compel myself to do it….I know that I only need to open my own books to hear what may be said against all this….But I feel resistance against everything ‘religious’ growing in me.”12

Bonhoeffer thus recognized that his devotional life in the 1940s did not match his earlier writings. By justifying his growing indifference about reading Scripture as part of his rejection of “religion,” he signaled that he was moving away from his earlier teachings.

BONHOEFFER’S DOCTRINE OF SCRIPTURE

However, Bonhoeffer’s doctrine of Scripture remained constant throughout his career. Though he studied under liberal theologians, he became entranced with Karl Barth’s dialectical theology (also known as neo-orthodox theology). Barth rejected nineteenth-century-style liberal theology, which saw Scripture as fallible human words expressing the writers’ subjective religious experiences. Instead, Barth insisted that all Scripture is the Word of God. However, by this he did not mean that Scripture was historically accurate; in fact, he did not think Scripture had anything to do with empirical reality. Barth divided knowledge into two separate realms—religious and empirical, and the Bible is religious truth, not empirical truth. Barth never embraced biblical inerrancy and readily admitted that higher biblical criticism had academic legitimacy. However, he thought that the historical accuracy of Scripture was irrelevant. Thus Barth (and Bonhoeffer) considered apologetics misguided, because it transgressed the boundaries separating the empirical and religious realms.13

Bonhoeffer shared Barth’s view that Scripture is completely true, but only in a religious sense, not as a report of empirical reality. Bonhoeffer often criticized the doctrine of verbal inspiration. He accepted the validity of biblical criticism, but maintained that even those passages that are not historically accurate are nonetheless the Word of God. According to Bonhoeffer, even though historical criticism has proven that Jesus did not speak some words ascribed to Him in the Bible, this makes no difference in interpreting Scripture. We must still rely on and preach the whole Bible and keep moving, like one crossing a river on an ice pack that is breaking up.14

Inspired but Inaccurate

In a 1925 essay, Bonhoeffer wrote that even if biblical critics proved that the person of Jesus is unhistorical in the empirical sense, this would not affect the content of God’s revelation, since His truth is revealed even through fallible words spoken or written by human instruments, such as the apostles. “By all means we must ascertain the fallibility of the [Scripture] texts and thereby recognize the miracle, that we always hear the Word of God from this human word.” Bonhoeffer stated that it really did not matter if particular miracles actually occurred as reported in the Bible. What is important is that we not dismiss them as irrelevant, but rather interpret them as testimony to God’s revelation.15 When he was an assistant pastor in Barcelona in 1928, Bonhoeffer told his congregation unequivocally that the Bible is filled with material that is historically unreliable. Even the life of Jesus is “overgrown with legends” and myth so that we have scant knowledge about the historical Jesus. Bonhoeffer concluded that “Vita Jesu scribe non potest” (the life of Jesus cannot be written).16

Bonhoeffer’s religious experience in 1931 did not alter his doctrine of Scripture. In one section of The Cost of Discipleship, Bonhoeffer affirmed the truth, reliability, and unity of the Scriptures in the strongest possible way. However, to avoid misunderstanding, he added this clarifying footnote: “The confusion of ontological statements with proclaiming testimony is the essence of all fanaticism. The sentence: Christ is risen and present, is the dissolution of the unity of the Scripture if it is ontologically understood….The sentence: Christ is risen and present, strictly understood only as testimony of Scripture, is true only as the word of Scripture.17

What Bonhoeffer is calling fanaticism here is the belief that the testimony of Scripture has ontological significance, that is, that Scripture is referring to things that really exist or have existed in the past. Bonhoeffer thus presented the truth of Scripture as nonhistorical, not testimony about some actual event.

Bonhoeffer’s doubts about the historical accuracy of Scripture are evident in Letters and Papers from Prison, too. For example, in a letter to Bethge, he expressed doubt about the historicity of Jesus’ prayer in the garden of Gethsemane, which, he surmised, the disciples surely could not have known, but nevertheless reported. He wondered how this could be.18

TRUTH, LANGUAGE, AND ETHICS

Bonhoeffer’s theology was on a completely different wavelength than American evangelical theology, because Bonhoeffer embraced a different view of truth and language. Bonhoeffer did not believe that truth can be contained in propositions or timeless principles. While working on The Cost of Discipleship, he wrote to a friend, explaining that truth is not timeless and universal, as many people assume it to be. Thus, when reading the Bible, “we may no longer seek after universal, eternal truths.”19

A Good Book

This view that Scripture does not contain any universal, timeless truths profoundly influenced Bonhoeffer’s ethical thought. In a 1929 lecture permeated with Nietzschean allusions, Bonhoeffer rejected the idea that Christian ethics is based on eternal principles or norms. “The New Testament contains no ethical precept which we may or even can adopt literally,” he stated.20 In The Cost of Discipleship, Bonhoeffer called fellow Christians to radical discipleship, to follow Jesus with abandonment. However, most evangelicals miss one of his key points: Discipleship does not involve learning the content of Jesus’ teaching and following it, according to Bonhoeffer:

What is said [in the Scriptures] about the content of discipleship? Follow after me, run along behind me! That is all. To follow him is something completely void of content…. Again it [discipleship] is no universal law; rather it is the exact opposite of all legality. It is nothing other than bondage to Jesus Christ alone, i.e., the complete breaking of every program, every ideal, every legality. Thus there is no further content possible, since Jesus is the only content.21

This may look good at first glance—of course Jesus is more important than anything else in the world, and we need to avoid legalism. However, Bonhoeffer is going further than that. He meant that no Scripture is to be taken as timeless truth, but only as God’s Word for today. The editor of the German edition of The Cost of Discipleship explained that this book “is not written, in order to be true ‘forever’; for Bonhoeffer was seeking what is true just for ‘today.’”22

This rejection of timeless, universal truths is a major theme in Ethics, where Bonhoeffer stated, “Principles are only tools in the hand of God that are soon thrown away as useless.”23 In one section of Ethics, Bonhoeffer explicitly rejected the idea that the Sermon on the Mount should be understood as ethical principles that could be applied to present situations.24 He also explicitly rejected the picture of Jesus as an ethical teacher or even an ethical model that Christians should pattern their lives after.

AVERSION TO CONVERSION

Aside from his faulty view of Scripture, Bonhoeffer’s doctrine of salvation was also problematic. As a Lutheran he embraced baptismal regeneration. Despite the heavy emphasis on calling people to radical discipleship, Bonhoeffer never showed any interest whatsoever in “converting sinners.” He did not believe that the salvation of souls was a central theme of Scripture, declaring in a 1935 sermon, “We must finally break away from the idea that the gospel deals with the salvation of an individual’s soul.”25 In Letters and Papers from Prison he reinforced this, stating that he did not think Sheol, Hades, or Christian redemption were metaphysical realities that exist somewhere in the past or will exist in the future. Rather, they are pictures of that which exists in the here and now.26 During his time in prison, Bonhoeffer complained that the New Testament was too overgrown with “redemption myths.” He preferred the Old Testament, since it seems less concerned with an afterlife, focusing instead on redemption coming in this present world. He stated, “In contrast to the other oriental religions, the faith of the Old Testament is not a religion of redemption. But Christianity has always been regarded as a religion of redemption. But isn’t this a cardinal error, which separates Christ from the Old Testament and interprets him according to the redemption myths?”27 Bonhoeffer thus wanted to replace the New Testament emphasis on individual salvation with a this-worldly view of life.

A Sweeping Salvation

Bonhoeffer’s view of salvation was also reflected in his distaste for conversion stories. Bethge observed that Bonhoeffer “was incensed by people who allowed themselves to be led full circle into reflecting upon their own beginnings, and was most strongly averse to any interpretation of The Cost of Discipleship or Life Together as special pleading on behalf of conversion.”28 Even though he experienced something of a conversion in 1931, he rarely mentioned it and later considered continuity, not conversion, a more apt description of the course of his own spiritual life.29 He even remarked late in life that he considered himself a “‘modern’ theologian who still carries the heritage of liberal theology within himself.”30

Bonhoeffer’s lack of interest in individual salvation may derive in part from his embrace of universalism. Although not easily apparent in The Cost of Discipleship, elsewhere in Bonhoeffer’s corpus it is more obvious. In Ethics Bonhoeffer stated:

In the body of Jesus Christ God is united with humanity, all of humanity is accepted by God, and the world is reconciled with God. In the body of Jesus Christ God took upon himself the sin of the whole world and bore it. There is no part of the world, be it never so forlorn and never so godless, which is not accepted by God and reconciled with God in Jesus Christ. Whoever looks on the body of Jesus Christ in faith can no longer speak of the world as if it were lost, as if it were separated from Christ.31

This is about as clear a statement supporting universalism as one could imagine, and it is reinforced elsewhere in Bonhoeffer’s writings.

EVALUATING BONHOEFFER

What then should we make of Bonhoeffer? While recognizing his many admirable traits—compassion, courage, commitment, and integrity—we should be wary of many elements of his theology. He imbibed large doses of Continental philosophy, including Kant, Hegel, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, and Heidegger—that profoundly influenced his worldview. His theology reflected Barth’s neo-orthodox theology, which called Christians to get back to Scripture as the source for religious truth, but without believing that Scripture is historically true. Bonhoeffer always considered himself a follower of Barth, though most Bonhoeffer scholars rightly consider Bonhoeffer more liberal than Barth. Stephen Haynes and Lori Hale, for instance, accurately present Bonhoeffer as a theologian “charting his own course in the charged space between liberalism and dialectical theology.”32

Richard Weikart is professor of history at California State University Stanislaus, and author of From Darwin to Hitler: Evolutionary Ethics, Eugenics, and Racism in Germany, as well as a book and essays on Bonhoeffer.

NOTES

- Jeffrey Pugh, Religionless Christianity: Dietrich Bonhoeffer in Troubled Times (London: T and T Clark, 2008).

- Joseph Fletcher, Situation Ethics: The New Morality (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1966), 149.

- Pugh, Religionless Christianity, 7.

- Eric Metaxas (interview), “The Authentic Bonhoeffer,” Christianity Today (July 2010), at www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2010/july/7.54.html, accessed October 25, 2010.

- Stephen Haynes, The Bonhoeffer Phenomenon: Portraits of a Protestant Saint (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2004), xiv.

- Bonhoeffer to Eberhard Bethge, July 16, 1944, June 27, 1944, May 5, 1944, in Letters and Papers from Prison, trans. Reginald Fuller (New York: Macmillan, 1971), 360, 336–37, 285.

- See Richard Weikart, The Myth of Dietrich Bonhoeffer: Is His Theology Evangelical? (San Francisco: International Scholars Publications, 1997); Weikart, “So Many Different Dietrich Bonhoeffers,” Trinity Journal 32 NS (2011): 69–81; and Weikart, “Scripture and Myth in Dietrich Bonhoeffer,” Fides et Historia 25 (1993): 12–25 (these articles are available at my website: www.csustan.edu/history/faculty/weikart).

- Bonhoeffer to Rüdiger Schleicher, April 3, 1936, in Testament to Freedom: The Essential Writings of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Geffrey B. Kelly and F. Burton Nelson (San Francisco: Harper San Francisco, 1990), 448.

- Bonhoeffer to friend, January 1936, in Bonhoeffer, Gesammelte Schriften, 6 vols. (Munich: Christian Kaiser Verlag, 1958ff.), 6:367–68.

- Bonhoeffer, Ethics, trans. Neville Horton Smith (New York: Macmillan, 1965), 294–95.

- Bonhoeffer to Bethge, January 31; 1941, June 25, 1942, in Gesammelte Schriften, 5:397, 420; and March 19, 1944, in Letters and Papers from Prison, trans. Reginald Fuller (New York: Macmillan, 1971), 234.

- Bonhoeffer to Bethge, June 25, 1942, in Gesammelte Schriften, 5:420.

- Karl Barth, Der Römerbrief (Munich, 1922); The Word of God and the Word of Man, trans. Douglas Horton, (n.p.: Pilgrim Press, 1928).

- Bonhoeffer, “Christologie,” in Gesammelte Schriften, 3:204–5.

- Bonhoeffer, Dietrich Bonhoeffer Werke, vol. 9 (Munich: Christian Kaiser Verlag, 1986), 318–20.

- Bonhoeffer, “Jesus Christus und vom Wesen des Christentums,” in Gesammelte Schriften, 5:137–38.

- Bonhoeffer, Nachfolge, in Dietrich Bonhoeffer Werke, vol. 4 (Munich: Christian Kaiser Verlag, 1989), 219–21.

- Bonhoeffer to Bethge, January 23, 1944, in Letters and Papers from Prison, 193.

- Bonhoeffer to Rüdiger Schleicher, April 8, 1936, in Gesammelte Schriften, 3:28.

- Bonhoeffer, “Grundfragen einer christlichen Ethik,” in Dietrich Bonhoeffer Werke, vol. 10 (Munich: Christian Kaiser Verlag, 1991), 332.

- Bonhoeffer, Nachfolge, 46.

- “Nachwort der Herausgeber,” in Bonhoeffer, Nachfolge, 307.

- Bonhoeffer, Ethik, 1–36.

- Bonhoeffer, Ethik, 228–36.

- Bonhoeffer, Gesammelte Schriften, 4:202.

- Bonhoeffer to Bethge, June 27, 1944, in Letters and Papers from Prison, 336–37.

- Ibid., 336.

- Eberhard Bethge, Dietrich Bonhoeffer: Man of Vision, Man of Courage, trans. Eric Mosbacher (New York: Harper and Row, 1970), 388–89.

- Bethge, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, 153–56.

- Bonhoeffer to Bethge, August 3, 1944, in Widerstand und Ergebung, 257.

- Bonhoeffer, Ethik, 53.

- Stephen R. Haynes and Lori Brandt Hale, Bonhoeffer for Armchair Theologians (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2009), 13.