Theological Trends Column

This article was published exclusively online in the Christian Research Journal, Volume 48, number 02 (2025).

When you support the Journal, you join the team and help provide the resources at equip.org that minister to people worldwide. These resources include our ever-growing database of more than 2,000 articles, as well as our free Postmodern Realities podcast.

Another way you can support our online articles is by leaving us a tip. A tip is just a small amount, like $3, $5, or $10, which is the cost of a latte, lunch out, or coffee drink. To leave a tip, click here.

Summary Critique

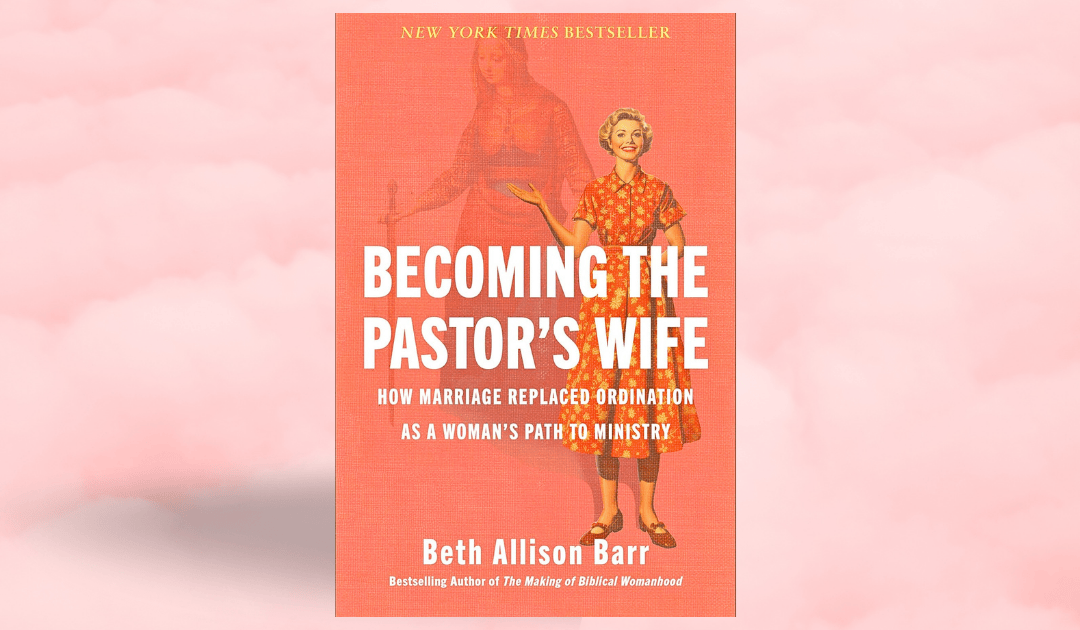

Becoming the Pastor’s Wife:

How Marriage Replaced Ordination as a Woman’s Path to Ministry

Beth Allison Barr

Brazos Press, 2025

In Becoming the Pastor’s Wife: How Marriage Replaced Ordination as a Woman’s Path to Ministry (Brazos Press, 2025), Dr. Beth Allison Barr sets out to make a historical and cultural case for the ordination of women. A lifelong Southern Baptist and the wife of a youth pastor, Barr’s academic research and focus on medieval history served as a catalyst to re-examine the place of women in the home and the church. How did it come to be that the role of pastor’s wife holds such prominence and power and yet, in most denominations, women cannot be ordained? Was it always this way? Barr came to believe that something strange happened in the aftermath of the Reformation. Whereas women had been on a trajectory to eventual and widespread ministry as priests and perhaps even bishops, the sudden ability of the clergy to marry spelled the re-subjugation of women.

In a review for Eikon: A Journal for Biblical Anthropology,1 I address Barr’s idea that women did and should exercise “independent” ministry alongside men. Here, I would like to examine some of the conclusions she draws from her historical scholarship. First, I will examine her claims about the Priscilla Catacombs, then those of Milburga, and finally those of Dorothy Patterson. I find, in conclusion, that though there may be some obscure evidence for women in clerical roles down the centuries, the tumult of the Industrial Revolution and subsequent overturning of normative gender assumptions created a vastly different theological milieu in which these issues came to be litigated. By viewing the past through girlboss lenses, Barr is blind to the full scope of the issues in play. Thus, her concluding “Can you imagine?” and “What if?” questions do not constitute the rhetorical coup she intends.

The Priscilla Catacombs. Reprising the same breezy, colloquial style of The Making of Biblical Womanhood: How the Subjugation of Women Became Gospel Truth (Brazos Press, 2021),2 Dr. Barr weaves together her own experiences as a pastor’s wife with her scholarship, anecdotes from the classroom, and her opinions about Dorothy Patterson, whom she is not shy to excoriate. One of the pillars supporting her case that women in the past exercised independent authority in the church rests on the Veiled Woman of the Priscilla Catacombs. On a trip to Rome with students, Barr took some time on her own to see the fresco. Buried underneath the city, the catacombs were the early gathering place of Christians. They hold a treasure trove of archeological data from the first centuries of the church. The Priscilla Catacombs, according to Barr, “contain so many images of women that, in trying to make sense of them, some scholars have postulated that the catacombs were a site of women’s worship” (p. 35). They contain one of the earliest depictions of Mary, the mother of the Lord, as well as His friends, Mary and Martha. For Barr, one of the most significant images “shows a veiled woman presiding” over “a communal meal,” the famous Fractio Panis (or Breaking of the Bread) (35).

It was another room, though, the Cubiculum of the Valeta, that ignited Barr’s imagination. This is the Room of the Veiled Woman.3 Scholars whom Barr trusts speculate that the woman is dressed in “what could be liturgical garb” and that the way she is holding her hands “would have been understood as religiously authoritative in the Greco-Roman world: the orans position” — standing with arms extended upward and palms open (36). This, for Barr, leaning on Karen Jo Torjesen, is “evidence of the earliest tradition of women preachers” (36). According to Torjesen, the order of widows commended by Paul to Timothy was, by the third century, “consistently listed with the clergy” (38).

The orans position alone, for Barr, is significant, but the figures on either side of the woman are pregnant with evocative feminist and liturgical meaning. They could be construed as that which “represents her ordination” and “her ministry” (39). Barr believes the scene shows a ceremony. “The seated man (the seat is a sign of authority) appears to wear a liturgical robe (the dalmatic) with a cloak (a pallium) around his shoulders.” He is “laying his hand on her shoulder” (38). In this scene, she holds a scroll, but in another scene, mirroring the other, she is “seated in a high-backed chair” (38). The scroll has been exchanged for a baby. What does this series of images signify? Barr’s tour guide believed they were “scenes from the deceased woman’s life — that in the center image she is shown praying in paradise, the left image is her wedding, and the right image is her as a mother” (39).4 Barr doesn’t think so. “It is also possible,” she writes, “that the threefold image represents an entirely different range of events from her life — that the center image portrays the woman in a religiously authoritative position, the left image depicts a consecration ceremony, and the right image depicts her fulfilling the function of her office, caring for unwanted babies” (38).

Barr believes “the Priscilla Catacombs present an abundance of depictions from the early centuries of Christianity representing women, many of whom are in authoritative positions” (40). Admitting that they do not “conclusively prove female leadership in the earliest centuries of the church,” Barr believes there is enough evidence to “undermine the claim that male-only leadership is a matter of ‘fundamental biblical authority’” (41).

Barr is wise to hedge her claims. While certainly gathering places of faithful Christians in times of persecution, the Catacombs were first and foremost funerary. They were monuments to the dead more than anything else. A quick search on the subject shows that the scholars Barr relies on fall outside mainstream opinion, which doesn’t necessarily make them wrong, but certainly increases the burden of proof for their arguments. In other words, we don’t know who she was and can only guess, which is what Barr has done.

Not being a scholar of medieval Christian history, I, of course, do not wish to tread where I have earned no hearing. Nevertheless, in the description of the veiled woman, and the consideration that she might have been enrolled among the widows, and even consecrated to perform some office, I do find it a bit curious that the “office” Barr believes she might be fulfilling is caring for unwanted babies. In the first place, is there any evidence that the infant is not the natural offspring of the woman? In the second place, I expect women would be given the “office” of caring for unwanted babies, not because of their independent ecclesiastical authority, but because the best person to care for a baby is a woman who knows what she’s doing. It is quite marvelous to think that the church would elevate and bless such a calling — the one of women caring for the lost, the vulnerable, the precious soul that had been cast down by the way. A woman lifting up her hands to heaven to receive such a blessing, the hand on the shoulder of commendation and grace, I’m not sure this is a picture of women’s liberation so much as an integrated and devout community of faithful men and women who love the Lord. And on that note, let’s turn to the second pillar of Barr’s historical argument, Milburga.

Milburga. Barr turns next to a seventh-century abbess near Shrewsberry, Milburga, who is sometimes depicted holding a crozier, the staff normally wielded by a bishop (57). Barr is captivated by the possibilities of Milburga’s long, “thirty-year tenure” as head of the double-monastery of Wimnicas (64). For Barr,

Milburga’s position casts doubt on claims from Christian leaders today that women have never exercised the pastoral role. Her story shows a time when women’s independent leadership in the church was more normative; it shows a woman whose ministry derived from her social status as an elite woman and from her ordination by a bishop rather than from her dependent status as a wife; most important, it shows how our understanding of terms like pastor and ordination stem more from historical context than the Bible. (55)

As one who is obedient to a bishop even in the modern day, though without any elite social status, I cannot help but ask what the word “independent” means in this context. Barr, throughout, views a relationship with a husband as one of “dependence” and ministerial possibilities as “independent.” This comes to the fore in her discussion of Milburga. Comparing the Southern Baptist Convention’s definition of a pastor to the role of abbess, Barr finds “similarities.” The modern pastor’s chief responsibility is to “preach and teach” (55). Milburga did just that. She was “charged with providing spiritual leadership to men and women” (56). Barr believes that Milburga not only taught both men and women but also likely celebrated the Eucharist in her local context. “Some scholars,” Barr insists, “charge that some historians have been ‘too quick to assume women’s total dependency on male priests, especially for the early medieval period.’ Evidence suggests some female communities could perform liturgies, including celebrating the Eucharist, and provide their own pastoral care without male clergy” (56).

Barr briefly discusses the evolution of liturgical practice through the Middle Ages. Essentially, as beliefs about the sacrament changed, the maleness of the priest became a crucial consideration (61–62).5 She marshals evidence that Milburga wasn’t merely a powerful abbess with sizable land holdings but acted in the capacity of an actual bishop. Barr uses the term bishop “intentionally to describe Milburga’s role as abbess for two reasons. First, I have found that when my students hear a feminine office (such as deaconess or abbess), they often presume the position is less authoritative than a male office (such as deacon or abbot)” (57–58). “This,” she says, “is an incorrect and anachronistic presumption, applying to the early church a modern complementarian understanding of women’s ministry that says women are only qualified to teach women and children (which, for some reason, makes them less authoritative because women and children are less important than men?)” (58). The second reason she calls Milburga a bishop is that the ecclesiastical hierarchy we see today “was still developing” (58).

Barr, though a “medieval historian who studies women and religion” (64), nevertheless found it hard to imagine what it would “have been like to grow up with the expectation (not just the possibility)” that a woman “could be an ecclesiastical leader as important as a bishop” (65). Barr believes that Milburga’s “ordination” would have been “celebrated and overseen by one of the most important religious leaders in her world” (65). Milburga “naturally would have provided pastoral care to men as well as women” (65).

Throughout Barr’s discussion of Milburga, I began to be uncomfortable with the term leader. From Stephen and James of the New Testament era (16) to “women’s ministry leaders” (7) to “SBC [Southern Baptist Convention] leaders” (5, 65, 159, etc.), the word applies to a whole range of actions and positions within the church. Is the modern concept of “leadership” something that maps well over Christian ecclesiastical concepts? I think this question is crucial for understanding the roles of men and women in the church today. The answer, at least from my point of view, is that it does not correspond well at all. What Christ in the church would consider a “leader” differs fundamentally from contemporary “leadership” ideals. To understand the dissonance, we must first consider Barr’s thoughts about the expectations imposed on the pastor’s wife.

Dorothy Patterson. If the reader could draw only one conclusion from Becoming the Pastor’s Wife, it would be that Beth Allison Barr disapproves of Dorothy Patterson, wife and “first lady” of Paige Patterson of the Southern Baptist Convention. For Barr, Dorothy Patterson is the icon of what ails women today. What was the chief sin of Dorothy Patterson? Summing up, it is that “Dorothy Patterson taught women that their primary ministry was to support their husbands and submit to male leadership.” Patterson believed that “women in early Christianity never served in leadership roles and that Jesus himself had ‘elevated’ the ministerial value of women’s domestic labor that supported the work of men” (35). Women, thus, would never be “leaders” in the sense that Barr advocates; and worse, they would always be “dependent” upon their husbands, always helping and never getting to be in charge.

According to Barr, this led Patterson to place weighty and unreasonable expectations on pastors’ wives. “A good pastor’s wife,” complains Barr in her description of Patterson, “was always ready to host; her home welcomed guests. A good pastor’s wife kept her house clean and safe for her children, providing a nurturing environment. A good pastor’s wife made sure her home was comfortable and orderly, filled with good food, love, and even a ‘company box’ that included ingredients ready to serve a quick meal for unexpected guests. The pastor’s wife, like her home, was always ready to serve” (87).

Patterson’s book, A Handbook for Ministers’ Wives (B&H, 2002), was one of the collection Barr had her research assistants glean for bad advice. In all, Barr and her assistants looked at 150 books published between 1923 and 2023 (xiii). They found a pervasive expectation that the pastor’s wife be “a ‘total partner’” (xiii). The pastor’s wife will often “participate” in the husband’s work. They are “in a ‘two-person single career’” (xiii). Patterson, for her part, believed that “the pastor’s home ‘should welcome the family and others whom God may send through its doors. If a minister never knows whether he has clean clothes to wear or if he must wash his plate before dinner, he is defeated before he begins’” (87–88).

Barr doesn’t object to good housekeeping and hospitality. For her, it is “when the advice becomes a universal demand.” Patterson got into the nitty-gritty of home decor (“should be furnished with taste and creativity,” she said), presentation (“keeping at least the entry and living room presentable and ready”) and sustenance (know how to make “a good cup of coffee” or, if Patterson herself is visiting, “a wonderful cup of tea”) (88). All of these instructions, and those of many more obscure authors, transform, for Barr, the simple fact of being a pastor’s wife into an intolerable burden.

It’s So Unfair. “Before the early twentieth century” — when, it’s worth noting, the Industrial Revolution was well underway — being married to a pastor “was not much different from marrying any other Protestant man” (109). The authority women had always had in the church and society at large was not particularly controversial, and pastors’ wives weren’t held to an extraordinary standard. But, after that, says Barr, “something significant had changed” (110). Marriage in the 20th century became “an expectation for good Protestant women, which meant that even women called to ministry were also expected to be wives” (110). This “blurred” roles women could occupy and “subsumed women’s work under that of a male household head,” especially in terms of wages (110). This affected the wives of the clergy. “As the correlation increased between being a wife and a godly woman, so did the correlation between being a woman in ministry and being the wife of a minister” (110). And, as she was already there, meekly in the background, there was no need to ordain her for the unpaid work she was expected to perform.

In the final chapter of the book, Barr asks a lot of questions intended to shake the reader out of complacency. “Can you imagine,” she asks, “if, when SBC women expressed a call to ministry, they weren’t told it was probably a call to marry a minister?” “Can you imagine,” she begs, “if pastors’ wives like [Joyce] Rogers and Dorothy Patterson had followed the lead of the 1983 resolution — encouraging women who worked outside the home as much as they encouraged homemakers?” (186). A few pages later she broadens the scope of her wondering. “What if,” she asks, “instead of fighting against one another, women encouraged one another in their callings — whatever those callings may be? What if our churches made room for both pastors’ wives and female pastors, for those who happened to marry pastors and those who chose not to marry at all?” (192–193). It’s so straightforward for Barr. If only Christians would, through a study of history, discover that the injunction against women holding ecclesial and spiritual authority is unnecessary. Women needn’t find a pastor to marry to enjoy meaningful work in the kingdom of God. If only.

It’s Going to Be Ok. It is so curious to me that Barr, in her description of the place of women in the church and the home, even dating a “significant” change in attitudes to the early 20th century, would never venture into the fascinating realm of technology and its fraught relationship with anthropology. The last century has been studied to the point of exhaustion, particularly the relationship between men and women. The least a person should be willing to acknowledge is that there are no easy answers, that nothing is as straightforward as it seems.

For Barr, the problem with the Dorothy Pattersons of the world is not that they thought women should try to make a nice home, but that they hung, relentlessly, onto the idea that women should not be ordained. Patterson had the audacity to impress these ideas on women who have no connection to the gendered world of the past.6 For no matter what Barr might suppose, whoever is painted in the Pricilla Catacombs and Milburga and all the other women she writes about in Becoming the Pastor’s Wife, they all had something essential in common. They lived in a world where the differences between men and women were so deeply assumed that no one would have ever been able to articulate them.

We don’t live in that world. Everything we say, think, and do is continually litigated in the public square. There are no givens — except that autonomy, independence, and “leadership” are unquestioned social and personal goods. The trouble for Christians is that we have to live simultaneously in secular, ideological egalitarianism and a pre-modern world governed by ancient Scriptures whose very first statement is that God created us “male and female” in His image (Genesis 1:26–27). How this works has been uncomfortably debated for over a century. Isn’t it curious that over and over and over again, orthodox Christian bodies have maintained a hard line against women in the pulpit and presiding over the Eucharist? It isn’t that they just haven’t learned enough history, or that they are culturally myopic, or that they don’t value the contributions of women. What if someone as well educated as Barr took the trouble to really understand why they won’t relent?

Anne Kennedy, MDiv, is the author of Nailed It: 365 Readings for Angry or Worn-Out People, rev. ed. (Square Halo Books, 2020). She blogs about current events and theological trends on her Substack, Demotivations with Anne.

NOTES

- See Anne Kennedy, “Book Review: ‘Becoming the Pastor’s Wife: How Marriage Replaced Ordination as a Woman’s Path to Ministry,” Eikon: A Journal for Biblical Anthropology, Spring 2025, https://cbmw.org/journal/book-review-becoming-the-pastors-wife-how-marriage-replaced-ordination-as-a-womans-path-to-ministry/. Eikon is the journal of the Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood.

- I offer a critical review of this book in Anne Kennedy, “Be Free! The Making of Biblical Womanhood — A Summary Critique of The Making of Biblical Womanhood: How the Subjugation of Women Became Gospel Truth by Beth Allison Barr,” Christian Research Journal 44, no. 03 (2021), https://www.equip.org/articles/be-free-the-making-of-biblical-womanhood-a-summary-critique-review-of-the-making-of-biblical-womanhood-how-the-subjugation-of-women-became-gospel-truth-by-beth-allison-barr/.

- For video of the images, see Beth Harris and Steven Zucker, “Catacomb of Priscilla, Rome,” Smarthistory, December 16, 2015, YouTube, video 11:04, the image of the veiled woman appears at 8:15ff, accessed June 13, 2025, https://smarthistory.org/catacomb-of-priscilla-rome/.

- Harris and Zucker believe that the high-backed chair resembles an ancient birthing stool, and that her position of prayer corresponds to depictions of the faithful in paradise. “Catacomb of Priscilla, Rome.”

- This is a fascinating shift in history that has been written about from as wide-ranging scholars as Hans Boersma to Ivan Illich and is probably not a good grounding upon which to litigate the ministry of women in the modern day.

- Ivan Illich, “Vernacular Gender,” Gender (Marion Boyars, 2009), 67–89.