This article first appeared in the Viewpoint column of the Christian Research Journal volume 39, number 01 (2015).

Viewpoint articles address relevant contemporary issues in discernment and apologetics from a particular perspective that is usually not shared by all Christians, with the intended result that Christians’ thinking on that issue will be stimulated and enhanced (whether or not people end up agreeing with the author’s opinion).

For further information or to subscribe to the Christian Research Journal please click here.

Luther’s assertion of individualism seemed novel and dangerous to many. However, this assertion of individual conscience was a different kind of individuality, for the medieval individual saw himself as part of a great chain of being, intimately linked to a great order that shaped the natural, religious, cultural, and political worlds. Luther’s assertion of individual conscience changed this understanding. As both a historian and a Protestant, Mark Noll regrets that the idea of individuality that emerged has brought “radical changes to European Christendom, and that some of those changes have been anything but healthy for Christian life and thought.”2

THE MADMAN

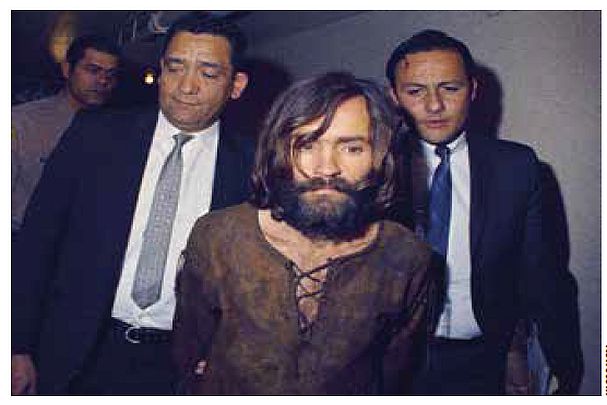

Almost half a millennium after Martin Luther’s stand before Charles V, another man stood accused, like Luther arguing his defense in Latin. However, in contrast to Luther’s compelling oration, this man’s Latin chant was erratic, and he was soon led from the court, scuffling with security. This disheveled man was the cult leader Charles Manson, charged with inspiring his followers to commit heinous killings.

Manson’s demented performance reflected an inner reality of megalomaniacal self-belief, and in the ultimate expression of radical individualism, the construction of his own religion. Manson’s religion was represented by a range of religious fragments—Christianity, Scientology, Nazism, and the self-help literature of Dale Carnegie. This belief system saw him attract a harem of impressionable female followers in the ‘60s counterculture epicenter of San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury. Such fragmentary thinking has long been linked to madness, and this was obvious in the case of Manson. However, Manson’s fusion of beliefs (absent his psychopathic application of them) would become typical of the American DIY (Do It Yourself) approach to religion in the coming decades and the increasing fragmentation of the contemporary individual.

INDIVIDUALITY, COMMUNALITY, AND FRAGMENTATION

Manson’s cult of personality was attractive to a countercultural movement that was attempting to break free from established forms of authority. It pursued a paradoxical goal. As writer Andrew Keen explains, “On one hand, the counterculture promoted the new man — a strongly individualistic free thinker liberated from the shackles of traditional community; on the other hand, however, it promised a return to the communitarian womb of the preindustrial village.”3 The seemingly warm and carefree “summer of love” labored under this impossible goal, moving into a darkness of fragmentation, exploitation, and narcissism, of which the Manson killings were emblematic.

Journalist Michael Walker4 notes that the killings rocked the counterculture’s belief that extreme communality and individuality could exist side-by-side if external authorities were rejected. Manson and his followers, as well as thousands of others, rejected vertical modes of authority. Yet this saw the birth of a dangerous and unbound form of tyrannical rule—a violent assertion of individuality in Manson’s complete control over his followers and a descent into a violence unseen in the mainstream it was rebelling against.

ICH BIN EIN BERLINER

Of course this had happened all before on a more terrifying scale. The ‘60s of Haight-Ashbury was in many ways a replay of the German Weimar Republic of the ‘30s, in which Berlin saw the rise of a counterculture in which “all authority was questioned,” writes historian Modris Eksteins, and a cultural mood existed that sought “to destroy all convention…because all existing standards were evil.”5

Like the hippies of Haight-Ashbury, the counterculture of the Weimar Republic looked to the horizontal to find authority, rejecting Europe’s Judeo-Christian heritage found in a vertical sense of authority. This horizontal search for authority looked to peers, to the collection of elements of various philosophies, and esoteric spiritualities. Sexual conventions were rejected; sound and motion was preferred over stability and tradition; experience was preferred over objective truth. Politics shattered into a kaleidoscope of parties and factions. Under the burden of trying to birth a culture that held together both individual autonomy and meaningful communal expression, life had fragmented.

Political scientist Robert Nisbet warned that a “society so inherently atomized” would yearn for a return to the stability of powerful, and often violent, authority. The Weimar Republic philosopher Ernst Von Aster noted that amongst this youth counterculture of “mutiny against authority and tradition,” there was a “blind discipline toward” an authoritarian leader.6 The journalist Peter Suhkamp worried that the young people who had thrown off authority “are ready for anyone who will command them.”7 The multimedia political movement known as Nazism, with its fragmentary and demented ideology, would soon be issuing the commands.

THE PHANTOM PUBLIC

Viewing history, we notice that a pattern emerges. Ironically, the search for individual autonomy leads to a horizontal mode of authority, in which the public becomes the dominant authority. This public is, however, as Søren Kierkegaard noted, “A phantom, its spirit, a monstrous abstraction, an all-embracing something, which is nothing, a mirage.”8 A phantom cannot lead nor inform; it can only offer a hall of mirrors, and eventually the fragmented individual and the mob yearn for order and discipline, of which there is no shortage of dictators and powerful leaders to oblige. One would hope that Western culture would learn from its history, yet our cultural amnesia sees this pattern repeated.

Today we see the search for individual autonomy alongside a quixotic search for community that does not cost, and all around we see fragmentation. The tendency of modern life to separate our lives into compartments, combined with a flood of information and pressures to self-create, has given birth to what Kenneth Gergen has labeled the saturated self,9 a mosaic form of being human. We seek individual autonomy, we worship freedom, yet philosopher Gilles Lipovetsky notes,

The individual appears more and more opened up and mobile, fluid and socially independent. But this volatility signifies much more a destabilization of the self than a triumphant affirmation of a subject endowed with self-mastery—witness the rising tide of psychosomatic symptoms and obsessive-compulsive behavior, depression, anxiety and suicide attempts, not to mention the growing sense of inadequacy and self-deprecation the more freely and intensely people wish to live, the more we hear them saying how difficult life can be.10

This fragmented self ultimately becomes what historian of psychology Philip Cushman calls the empty self, which “has made it much easier for advertising to exert influence and control.”11 This process is exacerbated as the Haight-Ashbury dream of radical individualism alongside utopian community is given new life by Silicon Valley, which offers us the mirage of a vibrant and connected online social life, without the restrictions and responsibility of traditional community. We seek connection but instead find online marketing gurus rewriting the very fibers of our neural pathways. Yes, we find some connection online, but increasingly a large portion of modern life is spent gazing into our screen, engaged in passive and solitary scrolling through the endless abundance of online options. Again, the individual in search of autonomy instead finds himself manipulated and led.

DISCIPLING THE FRAGMENTED SELF

The church is now challenged with an emerging understanding of the self that is fragmented and ethically contradictory. Those who go by the name Christian will be part religious and part pagan; much of the church will simply provide religious muzak for a secular culture. Instead, we must live out a reality in which the gospel touches every part of our lives. At this crisis point, we must return to Martin Luther. Luther was not rejecting the rule of the Roman Catholic Church and the political rule of Charles V in preference of his own personal authority. Rather, Luther was dramatically demonstrating in public form one of the foundational beliefs of the Reformational movement he would lead—sola scriptura. This was an assertion of the primacy of the Bible as the defining authority for the believer and the church.

The reassertion of this belief indeed opened up a sense of individuality. Yet it was an expression of individuality that flowered under the Lordship of Christ and was informed by the authority of Scripture that found home in the community of the church. Yes, it found meaning horizontally in community and in culture, but only when the horizontal impulse was met by the vertical authority of God. The horizontal and the vertical held together the symbol of the Cross, pointing a way to being truly individual, and truly in communion with humanity, under the ultimate authority of the King who gave His life, who leads us into holiness and wholeness, a world and a life coherent.— Mark Sayers

Mark Sayers is the senior leader of Red Church. He is the author a number of books, including Facing Leviathan: Leadership, Influence, and Creating in a Cultural Storm (Moody, 2014) and the forthcoming Disappearing Church: From Cultural Relevance to Gospel Resilience (Moody, 2016).

- Mark A. Noll, Turning Points: Decisive Moments in the History of Christianity (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 1997), 156.

- Ibid., 157.

- Andrew Keen, Digital Vertigo: How Today’s Online Social Revolution Is Dividing, Diminishing, and Disorientating Us (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2012), 104.

- See Michael Walker, Laurel Canyon: The Inside Story of Rock-and-Roll’s Legendary Neighborhood (New York: Faber and Faber, 2006).

- Modris Eksteins, Solar Dance: Van Gogh, Forgery, and the Eclipse of Certainty (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012), 65.

- Ernst Von Aster, quoted in Peter Gay, Weimar Culture: The Outsider as Insider (New York: Norton, 1968), 143.

- Peter Suhkamp, quoted in Weimar Culture, 143.

- Søren Kierkegaard, The Present Age: On the Death of Rebellion (New York: HarperPerennial, 1962), 33.

- See Kenneth J. Gergen, The Saturated Self: Dilemmas of Identity in Contemporary Life (New York: Basic, 2000).

- Gilles Lipovetsky, Hypermodern Times (Cambridge, UK: Polity, 2005), 55–56.

- Philip Cushman, Constructing the Self, Constructing America: A Cultural History of Psychotherapy (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1995), 80.