This article first appeared in the Christian Research Journal, volume 44, number 01 (2021). For further information or to subscribe to the Christian Research Journal please click here.

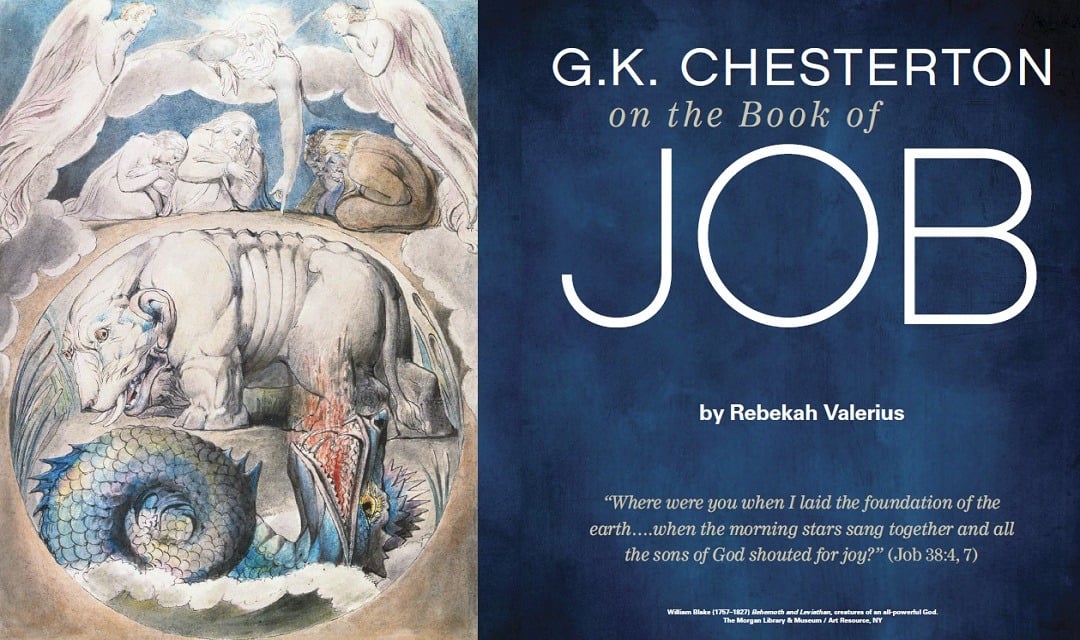

“Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth….

when the morning stars sang together and all the sons of God shouted for joy?”

(Job 38:4, 7)

Every cosmology is a theodicy or anti-theodicy. Every philosophy endeavors either to explain suffering or to explain it away. In other words, like the infamous elephant in the room, the problem of evil looms large in our attempts to understand existence. For the modern materialist, evil and suffering are illusions — evolutionary ploys that ensure survival in an indifferent universe. For the ancient pagan, suffering was the result of man’s failure to keep the gods happy, human existence being granted only as far as it served divine needs. For pagan and materialist alike, suffering is ultimately meaningless and existence is not a great good. There were no shouts of joy at the Big Bang.

A young G. K. Chesterton found himself immersed in the materialist view during his time in school. Unlike many who could compartmentalize the meaninglessness, he felt it acutely. He came to see that the only creed capable of challenging it must begin from the foundation that existence is good — that something is always better than nothing — even if it means a degree of suffering. “Our attitude towards existence,” he wrote, “if we have suffered deprivation, must always be conditioned by the fact that deprivation implies that existence has given us something of immense value.”1 Arguably, the goodness of existence is the grounding premise that led Chesterton to Christ, and it is one of the primary themes in his writing. “At the back of our brains,” he wrote, there lies “a forgotten blaze or burst of astonishment at our own existence.” He concluded that “the object of the artistic and spiritual life was to dig for this submerged sunrise of wonder; so that a man sitting in a chair might suddenly understand that he was actually alive, and be happy.”2

Chesterton’s determination to unearth this “submerged sunrise of wonder” is why an irrepressible note of joy rings throughout his literary corpus. Yet it is this element of joy that led many of his contemporaries to dismiss him as a superficial optimist — someone who was able to maintain the goodness of existence only by ignoring its pain. “The real paradox about Mr. Chesterton,” wrote one critic, “is that, with a tender and overflowing affection for all sentient things, he seems almost completely ignorant of the existence of sorrow and suffering.”3 Only a lack of genuine engagement with the problem of evil, many surmised, could account for Chesterton’s determined defense of the indefensible. Therefore, it might come as a surprise that Job, the book that plunges headlong into the problem of unjust suffering and where the central character curses the day he was born, was Chesterton’s favorite book of the Bible.

Chesterton’s Work on Job

Scholars have noted that Chesterton’s most popular novel, The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare (1908), could be read as a meditation on Job. Likewise, in two extended essays, Chesterton writes on Job exclusively: “Leviathan and the Hook” (1905) and “An Introduction to Job” (the latter being included in an illustrated edition printed in 1916). In various other works, we find Chesterton returning to the ancient poem again and again. He refers to it as an “inexhaustible religious classic,” writing that “centuries hence the world will still be seeking for the secret of Job, which is in a sense the secret of everything.”4 Chesterton could not help but join in on the search.

Chesterton and Cosmic Justice

Chesterton observes that the book of Job stands out in all of antiquity because of its unique views on justice. As mentioned, the pagans believed that the gods were fickle. The operations of the cosmos were reduced to a simplistic retribution principle: suffering was an indication that one had offended the gods in some way. Piety for polytheists centered on keeping the needy gods happy, mainly through ritualistic performance, something referred to by scholars as the Great Symbiosis.5 It was in one’s best interest to serve the gods, for prosperity would result. This is what the Challenger implies in the prologue of Job when he asks, “Does Job fear God for no reason?”6 In essence, he is asking if righteousness is its own reward, a question virtually unheard of in the ancient world.

In the pagan view, maintaining one’s innocence in the face of suffering was futile, for the capricious gods could not care less about righteousness. Justice aside, power must be appeased. Chesterton notes that Job’s friends affirm this view, for “all that they really believe is not that God is good but that God is so strong that it is much more judicious to call Him good.”7 It is important to see that these defenders of the Great Symbiosis receive God’s harshest rebuke: “My anger burns against you…for you have not spoken of me what is right.”8 Chesterton remarks that this rebuke “may have saved [the Jews] from an enormous collapse and decay.”9

For when once people have begun to believe that prosperity is the reward of virtue their next calamity is obvious. If prosperity is regarded as the reward of virtue it will be regarded as the symptom of virtue. Men will leave off the heavy task of making good men successful. They will adopt the easier task of making out successful men good. This…is the ultimate Nemesis of the wicked optimism of the comforters of Job. If the Jews could be saved from it, the book of Job saved them.10

Justice cannot be reduced to a simple equation, and for Chesterton, this was precisely what made existence so exquisite. He writes that “the true secret and hope of human life is something much more dark and beautiful than it would be if suffering were a mark of sin.”11 Instead, the book of Job communicates that the cosmos has not been imbued with God’s justice alone (if it were, who of us would survive?).

Chesterton and Cosmic Riddles

“The book of Job is chiefly remarkable,” writes Chesterton, “for the fact that it does not end in a way that is conventionally satisfactory.”12 The book seizes the simple justice formula of Proverbs — namely, that the wicked suffer and the righteous prosper — and summarily turns it on its head. As readers, we are left dazed by the operation, and when God finally enters the scene, His words do little to put justice back in its proverbial place.

In the prologue of Job, we learn that Job is chosen to suffer not because he is the worst of men but because he is the best: “Have you considered my servant Job, that there is none like him on the earth, a blameless and upright man, who fears God and turns away from evil?”13 Adding to our dissatisfaction, God then refrains from sharing this information with Job. George Bernard Shaw, the famous playwright and friend of Chesterton, summarized well the angst we feel: “If I complain that I am suffering unjustly, it is no answer to say, ‘Can you make a hippopotamus?’”14

Yet Chesterton reminds us that it is God’s evasive reply that brings comfort to Job, not his friends’ exhausting attempts to make exhaustive sense of his suffering.

Verbally speaking the enigmas of Jehovah seem darker and more desolate than the enigmas of Job; yet Job was comfortless before the speech of Jehovah and is comforted after it. He has been told nothing, but he feels the terrible and tingling atmosphere of something which is too good to be told. The refusal of God to explain His design is itself a burning hint of His design. The riddles of God are more satisfying than the solutions of man.15

In God’s response, Chesterton likewise discovered a refuge from oversimplified solutions to the problem of evil, most of which simply explain it away (like the materialist) or implicate God (like Job’s comforters). God reserves His fiercest rebuke to the “solutions of man” that purport to fully explain the cosmos: “God says, in effect, that if there is one fine thing about the world, as far as men are concerned, it is that it cannot be explained.”16 Though it is the great pleasure of mankind to seek to understand creation, we must keep at the back of our minds the reality of our finitude, especially when it comes to matters of cosmic justice.

Chesterton and Cosmic Joy

Chesterton classed Job as one of the greatest poems ever composed, primarily because of its enigmatic ending. “A more trivial poet,” he observed, “would have made God enter in some sense or other in order to answer the questions.”17 Yet the book of the Bible in which God gives His longest speech will not resort to a deus ex machina resolution. Instead, in God’s “colossal monologue,” He catalogues the works of His hands, unfolding “before Job a long panorama of created things.”18 Chesterton writes,

He so describes each of them that it sounds like a monster walking in the sun. The whole is a sort of psalm or rhapsody of the sense of wonder. The maker of all things is astonished at the things He has Himself made….Job puts forward a note of interrogation; God answers with a note of exclamation. Instead of proving to Job that it is an explicable world, He insists that it is a much stranger world than Job ever thought it was.19

Chesterton goes on to say that the genius of the poem is shown in how God’s descriptions of Creation imply not only that it is wonderful, but that it is good, its formation being an occasion for shouts of joy. He writes of the poet’s rendering of God’s speech:

Lastly, the poet has achieved in this speech, with that unconscious artistic accuracy found in so many of the simpler epics, another and much more delicate thing. Without once relaxing the rigid impenetrability of Jehovah in His deliberate declaration, he has contrived to let fall here and there in the metaphors in the parenthetical imagery, sudden and splendid suggestions that the secret of God is a bright and not a sad one — semi-accidental suggestions, like light seen for an instant through the cracks of a closed door.20

Comfort in Suffering

The book of Job tells us that all human attempts to resolve the problem of evil are inescapably oversimplified. This is at the heart of God’s question: Is Job — made a little lower than the angels, indeed, but infinitely farther removed in wisdom from God than the hippopotamus is from him — wise enough to govern the universe? Chesterton notes that Job, being an honest man, is silenced by this question. But Job is also comforted in knowing that the world is more complex than any human explanation can account for, especially when it comes to matters of suffering. Proverbial wisdom holds, yes, as we see at the end of the poem when Job’s fortunes are restored, for God takes pleasure in rewarding righteousness. But Proverbs is not the entire picture. The workings of the cosmos are far more intricate, and they do not run according to God’s justice alone, but in accordance with all of His attributes — His mercy and grace, as well as His love. This is the most important message that Chesterton gleaned from Job and one he sought to embody in all of his writing, causing that distinctive note of joy.

We must rest in God’s wisdom in how He laid the foundation of our world. And in the innocent suffering of Job, Chesterton concludes, the foundation was also laid for the “high and strange…paradox of the best man in the worst fortune” that is at the heart of the gospel of our salvation.21 The book of Job prepares us for the most extraordinary of all riddles — that comfort can be given through a God that suffered, encouraging us to take heart through our own tribulations.22

Rebekah Valerius holds a BS in biochemistry from the University of Texas at Arlington and an MA in apologetics from Houston Baptist University.

NOTES

- G. K. Chesterton, “The Philosophy of Gratitude,” The Chesterton Review 14, no. 2 (May 1988), 177–79.

- G. K. Chesterton, Autobiography (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2006), 99.

- Mark Knight, Chesterton and Evil (New York: Fordham, 2004), 17.

- G. K. Chesterton, “Leviathan and the Hook,” The Speaker, September 9, 1905, http://www.gkc.org.uk/gkc/books/Articles_for_Speaker.html#b05.

- See John Walton, The NIV Application Commentary: Job (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2012). 6 Job 1:9. All Scripture quotations are from the English Standard Version.

- G. K.Chesterton, “The Book of Job,” in G. K .C. as M. C.: A Collection of 37 Rare G. K. Chesterton Essays, ed. J. P. de Fonseka (London: Methuen and Co., 1929), 43.

- Job 42:7.

- Chesterton, “The Book of Job,” 50.

- Chesterton, “The Book of Job,” 51.

- G. K. Chesterton, “Leviathan and the Hook.”

- Chesterton, “The Book of Job,” 51.

- Job 1:8.

- As quoted in Walton, The NIV Application Commentary: Job, 397. This quip from Shaw is only reputed to have occurred.

- Chesterton, “The Book of Job,” 46–47.

- Chesterton, “The Book of Job,” 47.

- Chesterton, “The Book of Job,” 44.

- Chesterton, “The Book of Job,” 48.

- Chesterton, “The Book of Job,” 48.

- Chesterton, “The Book of Job,” 48–49.

- Chesterton, “The Book of Job,” 51–52.

- John 16:33.