This article first appeared in the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL, volume 36, number 02 (2013). The full text of this article in PDF format can be obtained by clicking here. For further information or to subscribe to the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL go to: http://www.equip.org/christian-research-journal/

SYNOPSIS

The Christian thinkers who developed just war theory (JWT) never could have foreseen the types of warfare in which we find ourselves engaged today. Their moral reasoning was sound and served as a powerful means to evaluate and constrain the actions of nation-states in conflict. Our challenge in applying JWT today is that modern warfare rarely consists of conflict between morally accountable nation-states. Instead, it is marked by “asymmetrical” wars between nation-states and widely dispersed but ideologically connected combatants who are driven by a mindset completely antithetical to the tenets of JWT. In that context, the moral considerations of warfare must remain consistent with JWT while taking the realities of modern conflict into consideration. We have the technological expertise to strike enemy combatants at a distance with little risk of personal harm. But that capability should never allow us to use it in ways that would make it easier to justify going to war in the future. JWT was developed based on objective moral standards of justice. For that reason it is, and will remain, applicable to all manner of war fighting. Though the tactics with which we wage war may evolve, Paul’s charge that the institution of government is the only proper authority to “bear the sword” (Rom. 13:4) requires that the reasons we consider war, and the ways in which we conduct war, cannot betray or dilute a godly standard of justice.

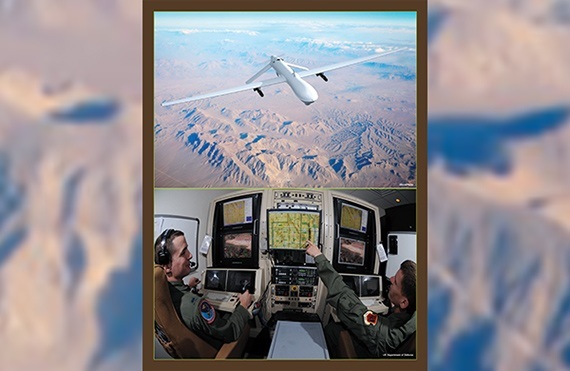

The twenty-first-century battlefield is unique in human history. Though fighting still results in spilled blood and the physical sacrifices entailed with “boots on the ground” in foreign lands, it is also a war waged amidst the air-conditioned comfort of humming computers and high-definition video feeds. In rapidly emerging ways, it is conflict at a distance, marked by the mind-boggling reality that an Air Force lieutenant in Las Vegas, Nevada, can unleash the hell of war on human beings on the other side of the planet, and then go home for dinner with his wife and kids.

St. Augustine and Thomas Aquinas were two of the most powerful intellects in the history of Christian theological/philosophical thinking and the primary architects of just war theory (JWT), but neither of them could ever have imagined the possibility of this type of scenario. The fact is that modern technology and the nature of asymmetric warfare have added new dimensions to the moral consideration of war. Earlier treatments of JWT in the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL provided valuable summaries of the tenets of the just war tradition in general.1 Here I will address some specific features of the ongoing Global War on Terror (GWOT) and explore ways in which Christian thinkers might apply the tenets of JWT to the contemporary battlefield.

To that end, it is important to understand that JWT actually consists of three areas of consideration: (1) The reasons that would validate a nation entering into war (jus ad bellum); (2) The ethical considerations for how to conduct war once engaged in it (jus in bellum); and (3) The moral obligations for actions taken once the war is over (jus post bellum).

The moral defensibility of the myriad of decisions that led dispersed aggressor with very limited means of supply and to entering the GWOT has been bantered about for the last decade. With the understandable disagreements about the Iraq War aside, there does seem to be a consensus that the United States was justified in entering what we now know as the GWOT. That being said, we should recognize that jus ad bellum and jus in bellum are not mutually exclusive. There has always been a legitimate debate about whether it is even possible to conduct a war justly if it was entered into unjustly. Likewise, a nation could wage a justly declared war unjustly. In response to these actualities, some have claimed that JWT is nothing but an obsolete and untenable window dressing used to rationalize national self-interest. I disagree. Instead, I suggest that the tradition itself remains fundamentally intact but is simply in need of revision that takes modern realities into account.

Just war ethicists have argued about these issues for centuries. Their discussions have led to conclusions that span the spectrum from the demand for absolute pacifism to the view that going to war is the only morally justifiable position. JWT was developed because the nature of war inevitably brings objective moral principles into conflict. We are bound by the objective moral duty to value and protect human life— an obligation that always requires us to differentiate between murder and justified killing. While the pacifist impulse should always attract our moral sensibilities, JWT attempts to identify what constitutes morally legitimate exceptions for the taking of human life.

JUSTIFYING JUST WAR

There are assumptions embedded within the just war tradition that force us to consider some aspects of our engagement in the modern GWOT. One of these is that JWT developed from an amalgam of several similar schools of ethical thought as a way to restrain nations from going to war, and to put curbs on the conduct of those nations in the event they did go to war. For those reasons, the theory is quite relevant and applicable to what is termed a symmetrical conflict between sovereign nation-states. But today’s GWOT is almost always an asymmetrical struggle between nation states on one hand and ideologically affiliated combatants who owe no allegiance to any particular national government on the other.

This asymmetry renders some tenets of JWT hard to evaluate. For example, it is difficult to legitimize the authority to wage war in the case where one of the belligerents lacks any legally recognized leadership. It is equally difficult to assess the proportionality of a response between a nuclear-armed superpower that is the victim of an attack and a surreptitious, nonuniformed aggressor who fades into the shadows after the attack. Likewise, it is almost impossible to determine the reasonability of success for either side in a conflict where a superpower with an overwhelming weapons arsenal responds to an organizationally and geographically

support. History has proven that the reasonability of success for either side in this case is very low. For reasons like these, the conduct of warring parties requires a nearly case-by-case consideration of what constitutes jus in bellum.

ROBOTIC ARMS

It should come as no surprise that the capability for a drone attack as described above is no longer a scene from some science-fiction action film. Combat incursions similar to this occur nearly every day against targets in the Middle East. In fact, the expansion of the use of unmanned aerial vehicles in offensive air combat operations is happening so rapidly some have speculated that the current crop of fighter jets rolling off the assembly lines will be the last of the manned fighter aircraft in the U.S. defense inventory.2

The move to remote-control combat is not just an aviation anomaly. Robots are being designed and deployed in all manner of missions to include battlefield surveillance, anti-sniper, IED disarming, night sentries, and equipment carriers.3 Future plans include ground and seaborne attack and even space-based weapons systems. As it relates to JWT, the ethical considerations that come with this technology are two-sided. On one hand, the benefit of mechanical warfare at a distance is that it provides a greater level of safety to the real people that would otherwise be tasked with accomplishing these missions. This is a good thing. But the margin of safety for those conducting the attack must be balanced with the probability that remote targeting leaves noncombatant, innocent human beings in danger of suffering harm.

It is a fact that there have been numerous incidents where jus in bellum has been violated by errant remote weapons deliveries. Going forward, this should be of grave concern for those who take JWT seriously. Perfecting sensor technology may reduce noncombatant casualties in the future, but it can never erase them. However, it is also true that the lengths to which our political and military leadership go to prevent this from happening through self-imposed rules of engagement are laudable. Continued advancements in technology have made our ability to discriminate between targets historically unprecedented. For this reason, I believe a more troubling issue with regard to remote warfare is that it exposes yet another hidden assumption within JWT—that the obligation to conduct war justly exists partly in light of an inherent risk of personal harm to those who wage it. This is a risk that robotic weapons systems effectively remove.

In the words of a Russian Orthodox chaplain in Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s epic, The Red Wheel, “War divides, yes—but it also creates comradely union, it calls on us to sacrifice ourselves—and how readily men answer the call! When you go to war, you risk being killed yourself. Say what you like, war is not the greatest of evils.”4

Historically, the threat of personal injury to those who make the decision to go to war has always tempered their actions, either by the motivation to be honorable, professional warriors, or through the pure practicality of avoiding unnecessary human suffering on either side of the fight. Though the technologies that have allowed mankind to wage war from a distance have mitigated much of the personal risk that comes with that choice, until recently even these types of weapons systems have required their operators to at least be present somewhere in the theater of operations. But with the advent of remote controlled robotics, a person who decides to kill another may literally do so from the other side of the world, far removed from the risk of any physical danger to himself.

HAND SANITIZER

The fallout from this attribute of the GWOT remains to be seen but there can be little doubt its implications are vastly different from what combatants experienced in more conventional forms of war. One’s gut reaction to the personal effects of combat is haunting. As a former Army Ranger and psychology professor at West Point describes it:

[There is] tremendous and intense remorse and revulsion associated with a close-range kill. [As one veteran told me]: “I dropped my weapon and cried…I felt remorse and shame. I can remember whispering foolishly, ‘I’m sorry’ and then just throwing up.” Some are psychologically overwhelmed by these emotions and they often become determined never to kill again…The killer’s remorse is real, it is common, it is intense, and it is something that he must deal with for the rest of his life.5

To be fair, there is evidence of some level of post-traumatic stress disorder among drone operators who experience burnout and moral angst from the long hours spent tracking and attacking their targets.6 But it seems incongruous to compare this form of trauma with the visceral response to killing entailed by personal combat.

This difference is significant. Human nature is very adept at excusing morally problematic behavior. The propensity to do so is magnified when that behavior becomes impersonal and can provide a means to justify giving more and more autonomy to the robots we employ in battle. From legitimizing decisions made by remote operators during “the fog of war” and under rapidly evolving tactical situations, to allowing a future where autonomous weapons systems are capable of responding to “other weapons systems” without regard to bystanders who may be in the vicinity of those systems, the nature of remote warfare at some level sanitizes direct accountability for the consequences of those actions.7

Each of these factors can lead to what I believe to be the most insidious and harmful consequence that comes with removing human contact with the horrors of war: it anesthetizes our collective moral conscience in ways that will make it easier to rationalize future decisions about whether, and how, to conduct war. The young military officers who are pushing buttons today will be the generals and politicians making decisions about morally significant combat actions tomorrow.

We have already seen a glimpse into where this kind of thinking might lead in the bipartisan and rapidly expanding use of presidential “kill lists” of individual human targets in the GWOT. President George W. Bush approved forty-four such attacks in his eight years in office. In his first three years, President Obama sanctioned 239. This policy is “the assertion of a presidential prerogative that the administration can target for death people it decides are terrorists—even American citizens—anywhere in the world, at any time, on secret evidence with no review.”8

JWT was partially constructed on the notion that war should not serve solely as a means for revenge. The practice of “hitting terrorists before they hit us” does hold an appeal to pre-emptive justice for those who mean us harm. And while it is also true that the public is not, and should not be, privy to the intelligence that leads to these targeted kills, someone with accountability does need to be.

The inherent possibility of a misapplication of moral authority to a single individual’s decision should arouse our moral sensibilities. Perhaps this policy is only carried out against persons who pose a credible and imminent threat to America or its allies. If so, the Congress can and should be informed about these threats and can thereby provide oversight regarding the proposed action and whether it would be permissible under JWT. There is no doubt that our complacency on this point has awakened the moral indignity of our enemies and plays some part in their continuing zeal for jihad.

HOW DO YOU SOLVE A PROBLEM LIKE TAQIYYA?

This is not to say that the practice of targeting individuals on presidential “kill lists” violates JWT in and of itself. It is simply an observation that adherence to JWT demands that such a weighty moral decision should not lie in the hands of a single individual or even his small circle of advisers. That said, the very nature of asymmetrical warfare is what has brought this type of policy to fruition.

This war is being fought against a dispersed enemy who embraces an ethical mindset completely contrary to a Judeo-Christian worldview and the very sense of justice that led to the development of JWT in the first place. In contrast, the Islamist understanding of a just war is quite different from that which exists under JWT: “[The] western distinction between just and unjust wars linked to specific grounds for war is unknown in Islam. Any war against unbelievers, whatever its immediate ground, is morally justified….The usual Western interpretation of jihad as a ‘just war’ in the Western sense is, therefore, a misreading of the Islamic concept.”9

Here any moral restraints on the conduct of war are more likely to appeal to the expansion of the territory under Islamic control, to the Islamic warrior’s sense of honor rather than justice, and to “peace” as defined by a state of submission to the fulfillment of the Qur’anic command to spread Islam.10 Embedded within this philosophical framework, jihad contains a lesser-known doctrine that is highly relevant to this discussion. Based in the Qur’an, the Hadith, and in Islamic law, the doctrine of taqiyya allows that lying and deception are not only permissible, but can be obligatory, for Muslims dealing with unbelievers in order to achieve jihad’s “honorable” and “peaceful” ends.11 The resultant tactics— which JWT would deem reprehensible—have become perfectly acceptable to Islamists in their advancement of jihad.

This is the mindset that allows jihadists to conduct attacks from within mosques, knowing that our just war–based rules of engagement do not allow retaliation. It is what allows Taliban warriors to infiltrate the American-trained Afghan National Army, knowing that they can use their trusted insider status as an opportunity to murder American troops. It is what allows the use of women and children as decoys and the employment of suicide bombers in the killing of noncombatants. And it is what haunts U.S. planners with the possibilities for “suitcase” delivery of weapons of mass destruction or the waging of “cyber warfare,” either of which could be brought to bear by a single individual yet cause widespread destruction and noncombatant suffering and casualties.

Facing an enemy who embraces these tactics and threatens these kinds of possible scenarios forces us to reexamine the morality of our response in two ways. First, as discussed above, the technological capability to respond to combatants who operate in this manner allows that the targeting of individual persons may lie well within the realm of JWT even if it does not relieve us of the commitment to jus in bellum principles. Second, as the war in Afghanistan aptly demonstrates, I submit that the nature of asymmetric warfare has forced us to violate the just war tenet of proportionality.

Normally the jus in bellum tenet of proportionality is thought of in the sense of refraining from the use of excessive force against an overwhelmed enemy. But asymmetric warfare has turned that notion on its head. Instead, Afghanistan has shown that using too few troops violates the tenet of proportionality because it results in excessive losses to an underwhelming allied force.12 The long-term effect of this violation of JWT is that, instead of our breaking the enemy’s will to continue the fight, insider and IED attacks on our forces have succeeded in torpedoing our own political and economic resolve to endure, prolonged the indiscriminate killing, and thereby led to yet another violation of JWT—that we have no reasonability of success in such a fight.

JUST WAR – REVISED EDITION

In its earliest form, “classical” JWT addressed the ways in which individual Christians should approach conflict because it was “individual persons, not states, who kill and are killed in war.”13 Later, nation-states developed and the more “traditional” form of JWT evolved into the one we recognize today. But as the nuances of asymmetric warfare have become more prevalent, there is a small but growing community of academicians who are promoting a “revisionist” approach to the subject of just war. Not knowing the full implications of the views of this revisionist movement, it would be premature to endorse it. But it does seem appropriate to reconsider some tenets of JWT in light of modern realities and to treat some of the specific issues discussed above in a parallel category of just war thinking that is applicable to asymmetric warfare while still remaining consistent with the goals of traditional JWT. What we cannot do is compromise on the objective moral obligation to value and protect human life made in God’s image to the greatest extent possible.

Pro-life advocates are often accused of hypocrisy for speaking out against abortion and the like while seeming to show little opposition to wars that also kill human beings. This type of criticism betrays a misunderstanding of the difference between the intrinsic evil inherent in the intentional taking of innocent human life, and the contingent evil that results from the difficult decisions that characterize our consideration of JWT. But if we are to maintain a morally defensible position in these types of debates, we cannot look the other way when remote warfare threatens to diminish our abhorrence for war; when the ability to target individuals tempts us toward an unchecked and unhealthy enthusiasm for revenge; or when the asymmetric actions of our enemies goad us into continuing to spill the blood of our youth pursuing a victory we cannot define, while conducting a campaign we have no hope of winning.

Bob Perry, M.A. (Christian apologetics) Biola University, is a speaker with the Life Training Institute. A Naval Academy graduate and former Marine Harrier pilot, he has two sons who are currently serving their second combat tours as infantrymen in Afghanistan. Access his website and blog on Christian worldview issues at http://truehorizon.org.

NOTES

- See Michael McKenzie, “Just War Tradition,” Christian Research Journal 19 (Fall 1996), 10–17 (available at http://www.equip.org/articles/just-war-tradition/); James A. Borland, “A Nation Responds to Terrorism and War,” Christian Research Journal 24, 2 (2002): 32–41 (available at http://www.equip.org/articles/a-nation-responds-to-terrorism-and-war/.

- “The Last Manned Fighter,” The Economist, July 14, 2011, available at http://www.economist.com/node/18958487.

- John Markoff, “War Machines: Recruiting Robots for Combat,” The New York Times, November 27, 2010, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/28/science/28robot.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0.

- Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, November 1916: The Red Wheel/Knot II, trans. H. T. Willetts (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1999), 53–54. Emphasis added.

- Col. Dave Grossman, On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2009), 238–39.

- Rachel Martin, “Report: High Levels of Burnout in U.S. Drone Pilots,” NPR, http://www.npr.org/2011/12/19/143926857/report-high-levels-of-burnout-in-u-s-drone-pilots.

- Val Wang, “Robots at War,” Popular Science (April 2009 interview with P. W. Singer, Wired for War), available at http://www.popsci.com/military-aviation-amp-space/article/2009-04/robots-war?page=1.

- Katrina vanden Heuvel, “Obama’s ‘Kill List’ Is Unchecked Presidential Power,” Washington Post, June 12, 2011, available at http://www.washingtonpost.co#m/opinions/obamas-kill-list-is-unchecked-presidential- power/2012/06/11/gJQAHw05WV_story.html.

- Bassam Tibi, quoted in Jean Bethke Elshtain, Just War against Terror (New York: Basic Books, 2003), 130. Tibi is a professor of international relations and an internationally respected scholar of Islam.

- Ibid., 130–31.

- John Guandolo et al., Sharia: The Threat to America (Washington, D.C.: Center for Security Policy, 2010), 98.

- Nicholas Fotion, War and Ethics (New York: Continuum International Publishing, 2007), 115–16.

- Jeff McMahan, “Rethinking the ‘Just War,’” New York Times, November 11, 2012, available at http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/11/11/rethinking-the-just-war-part-1/.