This article first appeared in the Christian Research Journal, volume 40, number 06 (2017). The full text of this article in PDF format can be obtained by clicking here. For further information about the Christian Research Journal click here.

SYNOPSIS

Malcolm X is arguably one of the most important people in African American religious and political thought. He was a man heavily influenced by his own personal experiences and the historic moment into which he was born. Along with the societal hardships that accompanied being Black in America when Jim Crow discrimination was enforced by law, Malcolm’s family endured racial violence. His life trajectory began to be characterized by his rejection of the society that had rejected him. This landed him in prison, where he was converted to the Nation of Islam.

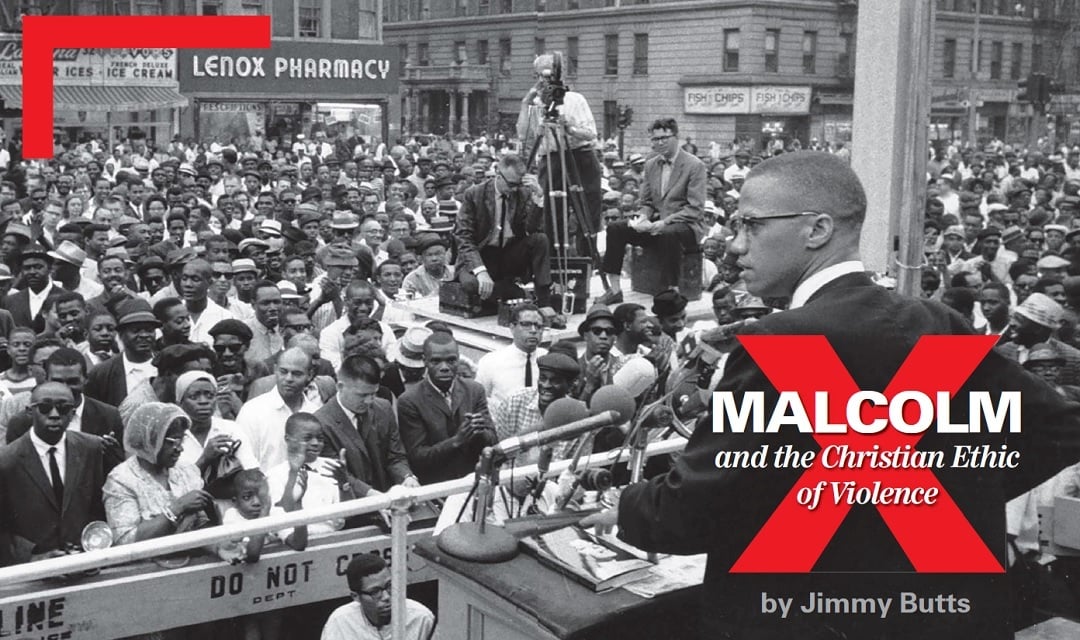

On release from prison, Malcolm rose in the ranks of the Nation of Islam and spread the message of Elijah Muhammad across America. His ministry developed in the context of the civil rights movement and was characterized as the violent alternative to the peaceful solutions that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. offered the nation.

Many who have rejected Malcolm’s social philosophy unfairly have interpreted him as a preacher of wanton violence against White people. However, this has left them susceptible to the charge of hypocrisy because there are elements within his ethic of violence that many Christians would defend if applied to their own lives.

Malcolm’s ethic of violence has at least three essential parts: self-defense, revolutionary, and retaliatory. A full theological examination of each of these exceeds the limitations of this article. However, one can conclude that Christian ethics allows for violence in the act of self-defense. Contrarily, Malcolm’s advocacy of retaliatory violence conflicts with biblical Christianity. Rather than softening the critique of Malcolm, I believe that this strengthens the argument against his philosophy because its precision protects the apologist from condemning what God allows. Therefore, African Americans should reject Malcolm’s teaching on retaliation because it conflicts with biblical Christian ethics.

Malcolm X is one of the most important figures in African American history. His social philosophy in response to the racial terror of the 1950s and ’60s is seen as the ideological opposite of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. He is most commonly known for and charged as an advocate of violence.1 However, professor Victor Okafor, scholar of African American Studies, argues that Malcolm’s social philosophy was a logical response to the challenges of his time.2

Contrarily, there are a variety of views about violence posited by members of the Christian faith; for example, Martin Luther King Jr. approached the same problem but arrived at a different conclusion. He explains, “The basic question which confronts the world’s oppressed is: How is the struggle against the forces of injustice to be waged? There are two possible answers. One is resort to the all too prevalent method of physical violence and corroding hatred. The danger of this method is its futility. Violence solves no social problems; it merely creates new and more complicated ones.”3

King argued that nonviolent resistance is a superior alternative to militant resistance. In fact, he stated that nonviolent resistance is “the most potent weapon available to oppressed people.”4 Another scholar who has considered the question of violence argues that Jesus’ crucifixion demonstrates what the Christian response to violence should be.5 South African theologian Desmond Tutu suggests that, although violence is evil, it is the lesser of two evils when used to stop oppression.6 Another perspective held by James Cone, founder of Black Liberation Theology, asserts that it is normal for Westerners to view violence expressed by disenfranchised people as unchristian.7

Where should the Christian land in this debate? Is the pacifist position the official biblical stance? Even Martin Luther King Jr. rejected the idea that all violence is evil.8 Viewing its position within the historic development of Christianity, evangelical ethicist John Jefferson Davis contends that “pacifism was a significant, though not dominant, presence in the early church.”9 With this diversity of thought, how should the Christian assess Malcolm X’s teachings about violence? We will look first at Malcolm’s life before examining his philosophy of violence.

THE LIFE OF MALCOLM X

Malcolm was born to Earl and Louise Little on May 19, 1925, in Omaha, Nebraska.10 Earl Little was a Baptist minister who was also an organizer for the UNIA,11 led by Marcus Garvey.12 Louise Little was from Grenada but looked like a White woman because her father was White. This gave Malcolm the distinct features of light skin and reddish brown hair.13

As a boy, Malcolm was greatly discouraged by a teacher who told him not to pursue law as a career but rather a career working with his hands, since he was Black.14 This encounter had a very negative effect on how Malcolm viewed Whites. During his youth, he would accompany his father on his preaching engagements, but Malcolm did not accept what his father taught about Jesus.15 This rejection of the biblical Jesus would continue throughout his life.

The Little family would eventually endure a tragedy from which they were never able to recover. Earl Little suffered the same fate as one of his brothers16 and was murdered by racists.17 As a result, Malcolm’s mother deteriorated psychologically from the many pressures of being a single mother of eight children. Malcolm was removed from the home and placed with a foster family because his mother was viewed as incompetent.18 Reflecting on this time, Malcolm stated, “I truly believe that if ever a state social agency destroyed a family, it destroyed ours. We wanted and tried to stay together. Our home didn’t have to be destroyed. But the Welfare, the courts, and their doctor, gave us the one-two-three punch.”19

As Malcolm grew older, he turned to the street lifestyle. During this era of his life, he sold marijuana,20 used cocaine, and committed armed robberies.21 He visited Harlem, was mesmerized by the experience, and decided that he could not be happy anywhere else.22 While in New York, Malcolm obtained the name “Detroit Red” to distinguish him from other “Reds” in town.23 His life of crime finally came to an end when he was caught by detectives after picking up a stolen watch from a jeweler’s shop where he had left it to be repaired.24

Malcolm was sentenced to ten years, but got out of prison after seven.25 This experience put him on a spiritual journey that began with hostility toward religion. Because of his antireligious attitude in prison, Malcolm gained the name “Satan.”26 However, Malcolm eventually obtained a hunger for learning and was an autodidact. In order to sharpen his ability to read and write, Malcolm began copying the entire dictionary. From that point on until the time he left prison, every free moment of time he had was spent reading books.27 He took courses in English and Latin,28 and was also on the debate team.29 Because of letters from his brothers Philbert and Reginald, Malcolm was introduced to the teachings of the Nation of Islam30 and became a convert.

From 1952 through 1960, “Malcolm virtually built the Nation of Islam into a coast-to-coast organization, attracting thousands of members and even more sympathizers. In this phase Malcolm not only expanded the Nation of Islam from a virtual back-street cult to a prominent new religion, but he himself elevated Elijah Muhammad on a platform of his own religious enthusiasm.”31 Malcolm grew as a national figure and was married to Betty X in January 1958.32 Eventually tensions within the religious organization mounted, and Malcolm was suspended on December 4, 1963. He subsequently announced his departure from the Nation of Islam on March 8, 1964.33

Reflecting on his time in the Nation of Islam, Malcolm explains that his break with the movement was based on his realization that what Elijah Muhammad taught in America was different from what was taught in the Muslim world.34 His pilgrimage to Mecca revealed to him that the teachings of Elijah Muhammad were not true.35 Further, Malcolm found out that Elijah Muhammad had impregnated some of his own secretaries.36 These were the two main reasons Malcolm left the movement. This new direction was never able to culminate because on February 21, 1965, Malcolm was assassinated.37

MALCOLM’S ETHIC OF VIOLENCE

Much of Malcolm’s ethic of violence is an articulation of his rejection of nonviolence. He argued that the expectation of African Americans to be nonviolent in the face of White terrorism was hypocritical. Pointing to the violence expected of African American soldiers to protect the country, he questioned, “How are you going to be nonviolent in Mississippi, as violent as you were in Korea? How can you justify being nonviolent in Mississippi and Alabama, when your churches are being bombed and little girls are being murdered, and at the same time you are going to get violent with Hitler, and Tojo, and somebody else you don’t even know?”38

Additionally, he criticized the societal expectation for Blacks to be nonviolent while no one expected Whites to be nonviolent in the face of attack.39 Agreeing with Malcolm, James Baldwin stated, “In the United States, violence and heroism have been made synonymous except when it comes to blacks.”40

Malcolm also rejected the philosophy of nonviolence from a utilitarian perspective. One can summarize his ethic of resistance to oppression by his oft-repeated statement: “By any means necessary.”41 He taught that it was necessary to conquer power with more power because that is the only way it can be defeated.42 For this reason, Malcolm believed nonviolence was an ineffective response to oppression.

In Malcolm’s opinion, nonviolence was also dishonoring to Black men. He suggested that “everything in the universe does something when you start playing with his life, except the American Negro. He lays down and says, ‘Beat me, daddy.’”43 Further, children will be ashamed of parents who take a nonviolent stance.44 In summary, as Cone explains, “Malcolm felt that nonviolence was ‘unmanning.’”45

Malcolm also asserted that the teaching of nonviolence was a trick by White society to cause Black people to be defenseless.46 He argued that Black preachers who advocated nonviolence were being used by Whites to disarm discontented Blacks, comparing them to Novocain, which enables you to suffer peacefully.47 Malcolm scholar Louis DeCaro argues that “Malcolm’s response to the prevailing ‘Christian’ philosophy that undergirded the civil rights campaign was, in this sense, quite sound. He instinctively understood that Christ’s famous words about loving one’s enemies and turning the other cheek had been taken out of context.”48

Having considered Malcolm’s critique of the philosophy of nonviolence, we now turn to examining three aspects of his ethic of violence. The first aspect of Malcolm’s ethic of violence is self-defense. He goes so far as to say that it is criminal to teach a person not to defend himself.49 In fact, he argued, “In areas where our people are the constant victims of brutality, and the government seems unable or unwilling to protect them, we should form rifle clubs that can be used to defend our lives and our property in times of emergency.”50 This demonstrates that he taught individual and organized

groups of people to use self-defense. Malcolm even offered to send people down to Florida and Mississippi to protect Martin Luther King Jr. using his “by any means necessary” ethic.51

Another aspect of Malcolm’s ethic is revolutionary violence. Drawing from what he understood as the tradition of the American Revolutionaries, he argued that African Americans were justified to use violence to overthrow the corrupt American government. He saw Patrick Henry as the embodiment of his social philosophy: “As old Patrick Henry said — I always like to quote Pat because when I was going to their school they taught me to believe in it. They said he was a patriot. And he’s the only one I quote. I don’t know what any of the rest of them said. But I know what Pat said: Liberty or death.”52 According to Malcolm, Henry’s reasoning was connected with his “ballots or bullets” philosophy.

As further encouragement toward revolutionary violence, Malcolm insisted that Black Americans should observe how Africans have obtained their freedom from Western colonialism using violence and apply those same tactics in America.53 He also pointed to historic figures such as Nat Turner, Toussaint L’Ouverture,54 and John Brown55 as examples of how to respond to Black oppression.

The final aspect of Malcolm’s ethic of violence is retaliatory violence. He argued that he reserved the right for maximum retaliation against racists.56 Malcolm believed that this concept was consistent with his religious convictions: “That’s why I am a Muslim, because it’s a religion that teaches you an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.”57 Malcolm went as far as encouraging murder-for-hire to communicate to the Klan that “we can go tit for tat, tit for tat.”58 He also wanted to start a fund to offer a reward for someone to kill a Mississippi sheriff who murdered some civil-rights workers.59

How should a Christian respond to this ethic?

A CHRISTIAN ETHIC OF VIOLENCE

A Christian ethic of violence does not require a pacifist position but allows for certain types of violence. Self-defense is a type of violence that Scripture allows. Thomas Aquinas brings a helpful biblical inference from the legal permissiveness of killing a home invader in Exodus 22:2: “Now it is much more lawful to defend one’s life than one’s house. Therefore neither is a man guilty of murder if he kill another in defense of his own life.”60 Going further, he suggests that since the intention of the defender is to save his own life, he is not at fault because his act has the additional effect of slaying the aggressor.61

Those who disagree usually point to the passage in Matthew 5:38–40, which seems to require Christians to endure violence passively. However, this passage was misused during the civil rights movement and is often misused currently. John Calvin argued that this passage refers to Christians being patient when wronged.62 In other words, Christians should have a greater amount of endurance for receiving wrong than those in the world.

Evangelical ethicist John Jefferson Davis comments:

The pacifist tradition is based largely, as we have seen, on a literal interpretation of the sayings of Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount. Such a hermeneutical approach is difficult to maintain consistently, since it overlooks the hyperbolic mode of speech deliberately used in order to arrest the listener’s attention and lodge the saying in the memory. Jesus also said that the lustful eye or hand was to be torn out or cut off, a forceful and memorable way of teaching the gravity of sin in the disciples’ life.63

Davis contends that love for neighbor does not require a pacifist ethic, but it is permissible to use “whatever force necessary” to protect yourself and your family.64 For this reason, the Christian can accept a self-defense ethic.

However, Malcolm’s teaching on retaliation is inconsistent with a biblical Christian ethic. Proverbs 20:22 addresses this issue directly: “Do not say, ‘I will repay evil,’ wait for the Lord, and he will deliver you.” The Christian is instructed to leave retaliation for an evil in the hands of God. Additionally, when Paul takes up this issue in Romans 12:17–19, he is not restricting self-defense but rather retaliation, according to John Calvin.65 Calvin goes on to rebut the misapplication of Matthew 5:39 as forbidding any form of self-defense, but, to the contrary, he argues that it forbids retaliation.66

As one reflects on the life and ministry of Malcolm X, it is understandable how he reached many of his conclusions. This, however, does not place him beyond criticism. I have demonstrated that Malcolm’s ethic of violence is multifaceted. If one desires to engage critically with his thought, indiscriminate condemnation must be avoided. When denouncers simplistically classify Malcolm as a hate-filled teacher of violence, they risk attacking a concept that the Bible allows. I have argued that self-defense is permissible within the scope of biblical ethics. The apologist must be careful not to allow his examination of Malcolm’s arguments to be prejudiced by his position on other issues. Rather than allowing an inconsistency to weaken his critique, the apologist can be more effective by making a precise assessment. I contend that Malcolm’s teaching of retaliation cannot be reconciled with biblical Christian ethics. For this reason, African Americans should reject Malcolm’s doctrine of retaliatory violence.

Jimmy Butts holds an AB in Bible and a BA in Christian Ministry. He is a pastor at Forest Baptist Church in Louisville, Kentucky. He has ministered to adherents of African American religions for the past ten years and is currently completing a Master of Divinity in Islamic Studies.

NOTES

- Karl Lampley, A Theological Account of Nat Turner: Christianity, Violence, and Theology (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 13. See also Robert Jenkins and Mfanya Donald Tryman, The Malcolm X Encyclopedia (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2002), 495.

- James L. Conyers and Andrew P. Smallwood, Malcolm X: A Historical Reader (Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 2008), 225.

- Martin Luther King Jr., A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr., James Washington (New York: Harper Collins, 1986), 7.

- , 25.

- Charles Villa-Vicencio, Theology and Violence: The South African Debate (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1988), 271.

- , 76.

- James Cone, Black Theology and Black Power (New York: Orbis Books, 2011), 138.

- King, Speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr., 32.

- John Jefferson Davis, Evangelical Ethics: Issues Facing the Church Today, 3rd ed., (New Jersey: P and R Publishing, 2004), 242.

- Malcolm X and Alex Haley, The Autobiography of Malcolm X (New York: Ballantine Books, 1999), 1–3.

- The Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) was a Black nationalist organization formed in the early twentieth century as a means of uplift for African Americans. Wilson Jeremiah Moses, The Golden Age of Black Nationalism, 1850–1925 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978), 264.

- X, Autobiography, 1.

- Ibid., 2–3.

- Ibid., 38.

- Ibid., 5.

- Ibid., 2.

- Ibid., 10.

- Ibid., 14–20.

- Ibid., 22.

- Ibid., 101.

- Ibid., 112.

- Ibid., 76–78.

- Ibid., 99.

- Ibid., 151–52.

- Ibid., 154–56.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 174–75.

- Ibid., 157–58.

- Ibid., 185.

- Ibid., 158.

- Louis DeCaro Jr., Malcolm and the Cross: The Nation of Islam, Malcolm X, and Christianity (New York: New York University Press, 1998), 98.

- Manning Marable and Garrett Felber, The Portable Malcolm X Reader (New York: Penguin Books, 2013), 120.

- George Breitman, Malcolm X Speaks: Selected Speeches and statements (New York: Merit Publishers, 1965), 18.

- Malcolm X, Malcolm X: The Last Speeches, ed. Bruce Perry (New York: Pathfinder Press, 1992), 85.

- Ibid., 84–85.

- X, Autobiography, 301-305.

- Marable, Portable Malcolm, 389–94.

- Breitman, Malcolm X Speaks, 7–8.

- George Breitman, ed., Malcolm X: By Any Means Necessary (New York: Pathfinder Press, 2012), 192.

- Toni Morrison, ed., James Baldwin: Collected Essays (New York: Penguin Random House, 1998), 320.

- Breitman, By Any Means Necessary, 84.

- Breitman, Malcolm X Speaks, 150.

- Breitman, By Any Means Necessary, 66.

- Breitman, Malcolm X Speaks, 33–34.

- James Cone, Martin and Malcolm and America: A Dream or a Nightmare (New York: Orbis Books, 1992), 107.

- Breitman, By Any Means Necessary, 143.

- Breitman, Malcolm X Speaks, 12.

- DeCaro, Malcolm and the Cross, 192.

- Breitman, Malcolm X Speaks, 22.

- Ibid.

- Breitman, By Any Means Necessary, 93, 95.

- Ibid., 124.

- Breitman, Malcolm X Speaks, 65–68.

- Breitman, By Any Means Necessary, 108.

- , 109–110.

- Breitman, Malcolm X Speaks, 76–77.

- Breitman, By Any Means Necessary, 172.

- Breitman, Malcolm X Speaks, 113.

- Ibid., 104.

- Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica (Claremont, CA: Coyote Canyon Press, n.d.), 54962–9, Kindle.

- Aquinas, Summa, 54969.

- John Calvin, Commentaries on the Epistle of Paul the Apostle to the Romans, trans.Henry Beveridge (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2009), 298–301.

- Davis, Ethics, 244.

- Ibid., 246.

- Calvin, Romans, 471–73.

- John Calvin, Commentary on a Harmony of the Evangelists, Matthew, Mark, Luke, trans.William Pringle (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2009), 298–99.