This article first appeared in the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL, volume 36, number 05 (2013). The full text of this article in PDF format can be obtained by clicking here. For further information or to subscribe to the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL go to: http://www.equip.org/christian-research-journal/

Among the great powers and gifts of the world’s literature is its ability to convey not only an overt ideology or simple plot but also an entryway into a culture not one’s own. In reading and reflecting on the words of another, the reader is given the opportunity to see from a foreign perspective—even if the book was written within blocks of the reader’s home. Especially through the development of characters, an author will present a window into what it may be like to be someone outside of the reader’s usual frame. By spending time with a book’s protagonists and witnessing their interactions with personal and ideological conflict, readers take up the privilege of practicing empathy in low-impact ways, without risk of actual attachment. And prospering our sense of empathy is essential as Christians so that we may learn to interact with others responsibly and with compassion.

Comic books, as one of the several vehicles for narrative communication, provide the same opportunities for enlarging our understanding of others that we find in prose fiction. In some ways, characters conveyed simultaneously through words and images may connect even more immediately with readers than those we encounter through text alone. It is little surprise, then, that we should discover a wealth of opportunities for gaining greater empathy through manga (comics produced in Japan).1 Manga, after all, covers as broad a range of stories as the American literary terrain.

Expanding in Empathy through Exploration. In Children of the Sea, Daisuke Igarashi’s five-volume cosmological realist-fantasy, we find exploration of a thoroughly non-Christian theory of galactic unification through what the book terms “the ghosts of the sea.” Igarashi might be the Haruki Murakami of comics, presenting handfuls of ideas through ephemeral terms, leaving the interpretive heavy lifting largely in the reader’s hands. While wading into heady grounds, the author alleviates much of the burden by presenting winning characters with fascinating backstories. Additionally his illustrations deftly capture the wonder of the undersea half of God’s earthly creation; this further offers the reader the option to be swept up into something larger than the oversea world to which we are accustomed.

The benefits of reading Igarashi’s work are varied. By becoming comfortable with the kind of people who might believe the things to which Children of the Sea’s characters acquiesce, we are less surprised when encountering new belief paradigms in our real-life encounters. As long as people remain alien to us, we are unable to empathize with them— and if we are unable to empathize, then it is likely we are unable to love them and to communicate with them.

Igarashi succeeds at conveying the idea that there are realities whose truth is damaged by the restrictions imposed by our finite, inadequate use of language. Through his story, we might for a moment be given a vantage into the difficulty others may have in understanding our fumbling explanations of matters such as the Trinity, the kenosis, and such seemingly simple concepts as law and gospel.

Love and Loss. But ideological concerns are not the only aspects by which an appreciation of manga can benefit the neighbor-loving Christian. Mitsuru Adachi’s eight-volume baseball-and-romance series Cross Game concerns itself with the forms that love and filial loyalty can take as these relationships develop over several years. Adachi is well known for his fluid art style and subtle storytelling techniques. While conscientiously dropping clues to his intent, Adachi prefers to trust his readers to take up the interpretive responsibility with a minimum of the usual handholding. His stories tend to explore concepts of life, love, and loss (usually through the veneer of high school sports, often baseball)—and do so in a manner that his predominantly young male audience will find thrilling and humorous.

An early tragedy in the first volume (of eight) colors the remainder with a sense that we are observing families and friends who are learning to cope with grievous loss. While Cross Game most immediately tracks a fledgling baseball team’s efforts to go to Koushien (the Japanese high-school-level championships), the meat of the book concerns an exploration of love. Love for a girl. Love for family. Love for friends. Love for neighbors. Love for the departed. As a people whose principal tangible identification is to be their love one for another (John 13:35), Christians should find value in observing the variety of ways love can be expressed.

Compassion for the Conflicted. And while Christians’ hope that their identity is marked by love, establishing identity for the characters inhabiting Takako Shimura’s continuing series Wandering Son is a struggle that is becoming commonplace in contemporary cultural expression. On the cusp of junior high, Shuichi and Yoshino struggle with gender expression. Shuichi, a boy, finds himself increasingly wishing to dress as a girl, while Yoshino, a tomboy who already dresses in a nonfeminine manner, pushes against her culture’s suggestion that she ought to be more ladylike.

While Shuichi himself thus far only expresses through transvestitism and remains heterosexual, the book eventually and additionally treats discussion of transsexuality, gender identity, and what the experience of coming of age in such turmoil might entail. Wandering Son is a brilliant work and will be valuable for interested Christians, as it presents deeply sympathetic characters rendered with realism and compassion. And if believers are to interact with their friends and neighbors who have lived with similar experiences of sexual complexity, it is essential that we see them not as a kind of bizarre Other but as real people who are neither monsters nor unworthy of our compassion.

Exploring Our Humanity. Much further down the contemporary road of identity discovery, Naoki Urusawa’s eight-volume Pluto investigates the question of artificial intelligences, sentience, and personhood. Urusawa adapts an old arc of Osamu Tezuka’s Astro Boy, bringing the story’s elements into the twenty-first century and selling it as a detective thriller. Urusawa’s protagonist is a top-level detective with Interpol (and one of the seven most powerful robots on earth) and is investigating a series of murders of other powerful robots and civil rights advocates for robots. It’s an exciting story, told across the canvas of a futuristic society where robots live alongside humans in a kind of separate-but-equal paradigm.

As with much of the robotics-concerned science fiction of the twentieth century, Pluto explores the line between the artificial and the real—whether man might be capable of creating life in a manner mirroring his own creator. In the end, though, as with most science fiction, Pluto doesn’t take its own questions on this tack seriously enough to engender any real discussion of the matter. Robots as people, so far as Urusawa uses them here, function more as window-dressing for a good story than as futurist manifesto. What Pluto does do that may be of special interest to Christian readers develops as a byproduct of its robotic protagonists. In all the questioning of what it means to be a sentient robot, Pluto actually proposes more forcefully what it means to be human. With the rise of transhumanist endeavor, these questions are powerful fodder for the thoughtful believer. Urusawa’s own answer to the question of human identity is particularly grim and may find sharp resonance with the Christian expression of original sin. In asking ourselves to understand Urusawa’s perspective, we’ll almost certainly come to a better grasp of our own nature and that of our neighbors.

War. Urusawa’s explanation of human nature (and what may set humans apart from sentient robots) rests in our capacity for violence and hatred. Fumiyo Ko ̄no’s single-volume Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms investigates those themes across the aftermath of the bombing of Hiroshima. Set initially a decade after World War II, Ko ̄no’s bittersweet story concerns a young woman who survived the blast but seems lost in the question of what kind of person must be on the other end of the decision that killed so many of her family members.

In an era when America almost constantly finds itself involved in military applications of force, reading books such as Town of Evening Calm can be valuable in learning to empathize with those who may be on the other end of our national war efforts. As illustrated aptly in one of Robert McNamara’s eleven lessons in Fog of War, considering enemy targets as human is essential for maintaining proportionality in war. We are called to love our enemies, and as Christians we recognize that even those who oppose our national concerns may be either our brothers and sisters in the kingdom of Christ or perhaps future co-heirs in that citizenry should God’s grace prevail. In any case, if we are to show those of foreign soils the love, compassion, charity, and mercy of Christ, we must be willing to see them not as alien, but as our neighbors, created and cherished by God.

Cultural Differences. Even as we are called to relate to the lives and experiences of our enemies (and thereby love them), so too can we come to consider the lives and circumstances of those in cultures made foreign by time as well as by language and geography. Kaoru Mori’s ongoing series, A Bride’s Story, concerns marital customs and pairing in the nineteenth-century Caspian region. A principal storyline follows the early days of the marriage between twenty-year-old “old maid” Amir and her husband, twelve-year-old Karluk. Both characters are an adorable mix of insecurities as they attempt to negotiate a relationship in which culture dictates the husband ought to be the sturdy one while recognizing the wife’s age-born strengths and wisdom.

As the couple grows beyond the purely political motivation for their union and into a more easygoing mutual love and respect for each other, contemporary Western readers will find the opportunity to understand a culture and its people a little better. After all, social mores prompt us to see such practices as barbaric and rapacious. A twenty-year-old marrying a preteen strikes us as a horrifying picture. And yet the people whose cultures practiced (and may still practice) such customs are as much to be the focus of our love, earnest interest, compassion, and consideration as those whose traditions are more in line with our own. If we can empathize with those in a society that practices child-marriage, we may find ourselves better prepared to interact with those in cultures who cover their heads in public, think abortion a social good, or believe religion to be the source of most earthly evils.

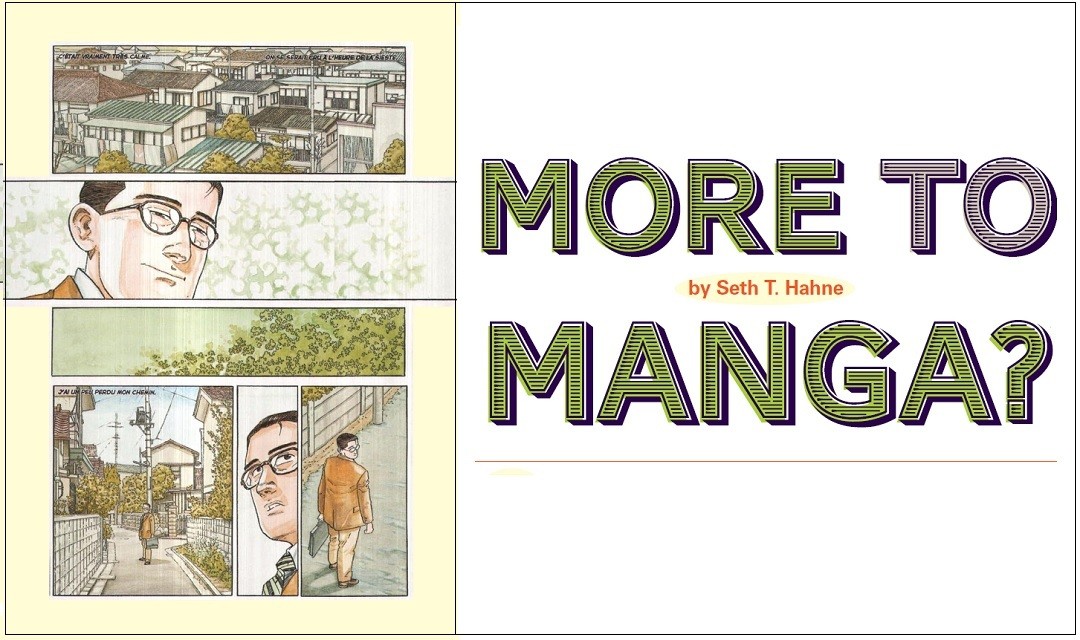

Finally, in better coming to appreciate the physicality of the environments in which others dwell, we may find ourselves able to empathize with the unique circumstances of others. The works of Jiro ̄ Taniguchi are beautiful, and they conspicuously detail the settings in which his characters exist and move. Perhaps the most luscious example of this is The Walking Man, in which a nameless protagonist simply goes on nearly silent walks, exploring a different aspect of his new town in every chapter. Taniguchi luxuriates in the world his walking man inhabits, giving the reader the opportunity to take in the wonder of the mundane. He allows us to better understand what this man’s life and world are like, and therefore some of the walker’s unique circumstances as well. From this we may learn to better appreciate how the worlds in which others live and grow might also affect who they are, who they may become, and the influences that bear on them day in and out.

This small selection of manga is only the slimmest gateway into a vast collection of works that, among other things, can encourage us to relate better to those who are not like us. As we find ourselves becoming interested in the foreign lives of these fictional figures, we will almost certainly discover the keys by which we may open the doors to better empathizing with those we would seek to reach with the good news of the Christian hope. —Seth T. Hahne

Seth T. Hahne is the founder of Good OK Bad, an Internet resource devoted to helping readers find worthwhile comics, graphic novels, and manga.

NOTES

- Some of the manga titles contain mild nudity, violence, and/or language.