A movie review of

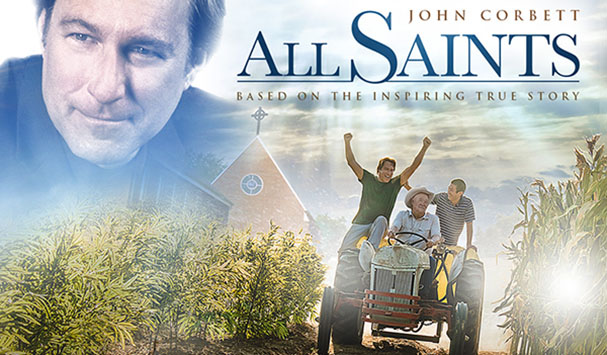

All Saints

Directed by Steve Gomer

(Sony Films, 2017)

The movie All Saints marks an interesting moment in American culture that apologists should note. The movie tells the true story of a salesman-turned-pastor whose dying church in rural Tennessee is revitalized after its members welcome a group of Christian refugees from Burma. It is a good story that’s worth telling, and the movie tells it well. The acting is good, there are some unpredictable plot twists to keep viewers interested, and the film’s portrayal of Christian faith is inspiring. The movie is especially good at showing the challenges that refugees face, especially in terms of mutual cultural misunderstandings with the locals.

But the reception of the film — how audiences reacted to it — is perhaps more instructive for cultural apologetics than the story of All Saints itself. This is a small, faith-based movie that only opened to $1.5 million its first weekend at the box office this August. That might sound like a lot for a film that only cost $2 million to produce and could possibly go on to make up to $10 million before all is said and done. That’s pretty good; but it is nothing compared to recent faith-based films.

Earlier this year, The Shack opened at $16 million and went on to make $57 million. Those numbers are fairly typical nowadays when movies like God’s Not Dead and War Room regularly gross around $60 million or more. Even a decade ago, Fireproof, the movie that started the recent trend of faith-based movies, made $33 million.

Obviously, Christian audiences liked these movies a lot more than All Saints. But critics didn’t. According to the movie review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes, only about 20 to 30 percent of reviews for faith-based movies tend to be positive. Fireproof was one of the better-reviewed movies (at 40 percent), but only 15 percent of reviews for God’s Not Dead were positive.

Suffice it to say that faith-based movies don’t have a good track record among film critics. So when All Saints got a 93 percent rating on Rotten Tomatoes, something is happening. Mainstream, non-Christian film critics really like this film. And these are the “liberal elites” writing in places like the Los Angeles Times!

Resisting the Culture War. Critics seem to appreciate that All Saints is not preachy like most Christian movies are — at least it is not preachy about theology and doctrine. All Saints focuses instead on preaching social justice, and it portrays Christians doing good work in the world. Now, one response an apologist could have is to dismiss mainstream reviewers as “liberals.” The church in the movie is an Episcopal congregation, after all, not an evangelical one. So perhaps mainstream critics only like All Saints because they care more about social justice than biblical truths like salvation through faith and the truth of the resurrection — the sorts of things preached in movies like God’s Not Dead that reviewers hated.

There is undoubtedly something to this cultural critique. It is not surprising that liberal film critics prefer movies about liberal Christians. But I would suggest that this “culture war” approach to interpreting the reception of All Saints is unhelpful for apologetics. The temptation to reduce everything to liberal-vs.-conservative politics not only results in alienating the non-Christians we claim to be witnessing to but also blinds us to the apologetically helpful suggestions the film is actually making about the church’s role in society.

Shining the Light of Good Works. All Saints starts with a backward-looking congregation, literally flipping through old photo albums, nostalgic for the days when their church was an important part of the town. They want to keep doing what they have always done, but their attendance is dwindling, and they find themselves in conflict with a church institution that focuses more on budget deficits than pastoral care.

But then the church’s routine is disrupted by the sudden presence of people in need, and All Saints becomes the inspiring story of renewal as the church becomes a community of self-sacrificial love willing to step out in faith to welcome strangers and to serve their material needs as well as their spiritual ones. In the end, there is a resurrection of sorts. We see a church raised from the dead to regain the social relevance it once had.

Importantly, this revival happens when the church turns outward, looking both to help those who showed up as outsiders and also to receive help from the wider community, instead of focusing inward on maintaining self-sufficiency. When the church faces a crisis toward the end of the film, even non-Christians show up to help out, because they can see the good work the church is doing. It is like Matthew 5:14–16 in action. In simplest terms, All Saints makes the argument that love is the best apologetic for the truth of the gospel.

The Apologetics of Love. If apologetics is defending the faith, then we should think about what are common objections to the faith. Many people have intellectual objections. They think it is irrational to believe in God or the Bible. But that is not the whole story. The majority of Americans still say they believe in God, yet fewer people are calling themselves Christians and attending church today. For some people, rational objections seem less decisive than moral objections.

We often think that non-Christians today are relativists who don’t believe in truth or moral conviction, but I’m not so sure. Young people today have strong moral convictions, as seen in their willingness to engage in political protest. They reject Christianity not because they think Christians have too many moral absolutes but because they think Christians don’t really care about morality. The refugee case raised by the movie is a good example. Christians say we believe in love and hospitality and helping those in need — and evangelical leaders have actually been speaking out in support of refugees lately — but evangelical Christians are still the most reliable supporters of politicians who demonize refugees and other immigrants. A similar story could be told about racial justice. This is why Christians have a reputation as hypocritical and judgmental.

Truth in Action. Now along comes this film that portrays Christians as actually good people, not hypocrites, and non-Christian critics respond positively. They like this image of the church. This might tell us something about how the church ought to respond to our culture. If we get out in the neighborhood and actually love people — before asking them to believe in Jesus, not after — then that would be the best proof that Christianity is true.

If the Resurrection is just a historical fact that happened 2,000 years ago, then non-Christians couldn’t care less. But if the risen Christ is someone whose transformative love we can know by experience in our lives today, then that makes all the difference. Christianity becomes a communal practice of love that we invite people into, not simply an abstract idea we affirm but which may not actually affect the way we treat those in need. —John McAteer

John McAteer is associate professor at Ashford University where he serves as the chair of the liberal arts program. Before receiving his PhD in philosophy from the University of California at Riverside, he earned a BA in film from Biola University and an MA in philosophy of religion and ethics from Talbot School of Theology.