This is an online Viewpoint article from the Christian Research Journal.

When you support the Journal, you join the team of to help provide the resources at equip.org that minister to people worldwide. These resources include our ever growing database of over 1,500 articles, as well as our free Postmodern Realities podcast.

Another way you can support our online articles is by leaving us a tip. A tip is just a small amount, like $3, $5, or $10 which is the cost for some of a latte, lunch out, or coffee drink. To leave a tip, click here

DON’T HEAR WHAT I’M NOT SAYING

It’s been called “a marvel”1 and “the Protestant magnum opus on sexual ethics we’ve been waiting for.”2 It’s also been called “Sacred Pornography,”3 a “Protestant bowdlerization” of Theology of the Body,4 and “a rhapsody over a very male-centered experience of sexual intercourse.”5 If you haven’t heard of it by now, welcome to the Twitterstorm. Josh Butler’s newly released book Beautiful Union,6 and the excerpt from chapter one titled “Sex Won’t Save You (But It Points to the One Who Will),” edited and posted by The Gospel Coalition (TGC),7 faced enormous backlash from evangelicals online — resulting in Butler’s resignation as a fellow for the newly formed Keller Center for Cultural Apologetics, but more recently from his role as a lead pastor at Redemption Church in Tempe, Arizona.8 Plenty of people read the book excerpt before it was removed from TGC and replaced with the whole of chapter one for more context. But at the pitch of the controversy, very few had actually read the entire book (it hadn’t yet been released). That snippet caused quite the scrap.

A common phrase in my home that comes up during arguments is don’t hear what I’m not saying. I believe many evangelicals missed what Butler was trying to say about the divinely iconic nature of marital sex, and instead heard something not only “gross” and theologically incorrect, but dark and dangerous (especially for women). What Butler meant in the book’s entirety and intention, and what people heard in that misbegotten article, were quite different; the reasons for this difference are emblematic of evangelicalism and worth understanding.

In Beautiful Union, Butler argues that marital sex is an icon we can look through to greater things, like a stained-glass window in a cathedral. The beautiful union of husband and wife, particularly as it’s enacted in fruitful and faithful marital sex, is meant to give us a vision of the transcendent mystery of God’s love, of Christ’s union with the church. Butler believes his iconic vision of sex contains encouraging truth for everyone, not just for married couples. Anyone can enjoy the substance of union with Christ, Butler writes, even if they don’t participate in the symbol of that union in this life.9 He maintains that the iconic nature of sex makes intuitive sense of the various biblical prohibitions surrounding it. Those boundary lines form the contours of a picture of God, such that sexual sin tells the wrong story about our Creator. Butler grounds his ideas in Scripture, especially in the opening chapters of Genesis and in Ephesians 5, though many have questioned the soundness of his exegesis. “I want to introduce you to an ancient vision,” Butler writes, “more poetic in nature.”10 He attempts to teach Christians embedded in a culture that is both porn-saturated and contraception-dependent how to see through marital sex to the beautiful, biblical, fruitful union of heaven and earth, which is the story of our redemption.

When Butler says, “sex is an icon,” he’s not just talking about body parts or mechanics. He routinely uses the word “sex” as a synecdoche, as a shorthand for a part (sexual union) that stands in for the whole (marriage), such that his references to the microcosm of sex are embedded in this larger macrocosm of marriage — and the macrocosm of marriage is itself embedded in the archetypal pairings of creation seen in the litany of Genesis 1 (heaven and earth, day and night, land and sea). This fractal picture of nested parts within wholes is his strongest defense against the accusation that what he’s talking about is pornographic. Porn is always and only about parts.

Butler clarified in an interview that his language surrounding the sexual symbolism of male and female — giver/receiver and generosity/hospitality — refers primarily to procreation.11 The husband gives his seed outside of himself (generosity) and the wife gestates the child of their love inside of herself (hospitality). The language isn’t meant to refer to genitals (who “penetrates” whom) or to positions (who’s on top) or to roles (who initiates): removing the assumption of fertility from sexual union turns Butler’s language into a dynamic of dominance and submission, which is not what he intended.

Because Protestantism has by and large incorporated contraception as a normal aspect of family planning, many are accustomed to thinking of sex as something that’s solely for bonding and pleasure. Only if and when you want to, you can opt in and upgrade your sex plan to include the “child bonus pack,” otherwise your default fertility setting is off. With the unitive and procreative aspects of sex experientially severed most of the time for most couples, that changes the way we hear euphemisms about sex in the manner Butler uses them. Generosity and hospitality make sense only within the framework of potentially fruitful non-contraceptive sex in which children are a blessing: this is the frame the Bible assumes. Outside of that frame, everyone is thinking in terms of body parts, positions, or roles in the sexual encounter, and this gets both overly explicit and weird really fast. Our habits affect our field of vision: we shouldn’t be surprised that contraception shapes perception.

Butler is first and foremost a pastor. He addresses his readers as “dearly beloved,” gently acknowledging the places of brokenness they may be coming from: the unhappily single and the unhappily married; the divorced, heartbroken, betrayed, or widowed; the sexually abused and the porn-addicted; the mother drowning in five kids and the woman grieving a stillborn child; the lonely, the cynical, those who hate their bodies, and those who’ve been rejected because of their same-sex attraction. The pages are peppered with personal anecdotes, pastoral consolations and warnings, and the liberal use of subheadings and italics that are common to blog posts (with the occasional “LOL!” and “Whoa!”). As such, it’s neither scholarship nor a “magnum opus”: it’s a popular book for folks in the pews.

Although Beautiful Union has flaws, the overall theological idea — the iconicity of nuptial union — is lasting: it already has lasted for two thousand years. The concept is venerable even if Butler’s rendering of it is not. I don’t agree with everything in it: the manner in which he works the metaphor becomes awkward, strained, and idiosyncratic at times (revealing his shaky grasp of the allegorical tradition), but I’m also convinced that the book’s content is neither pornographic nor pagan. The disgust with which Butler’s ideas were greeted says as much about evangelical assumptions regarding sex and icons as it does about his imprudent language and his offhand use of iconography as a framework. When it comes to misunderstandings this deep, it takes two to tango: both Butler and his readers are on the hook.

Butler is a non-denominational Reformed (in the broad definition as a Calvinist and a complementarian but a non-confessional Reformed Christian)12 evangelical attempting to reconnect to a mode of perception and biblical interpretation that thrives in Eastern Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism but has been largely untapped (and at times rejected) by Protestants for centuries. I think this deep cross-cultural difference accounts for the lion’s share of the misunderstandings fueling the controversy.

ONE DOES NOT SIMPLY BORROW AN ICON

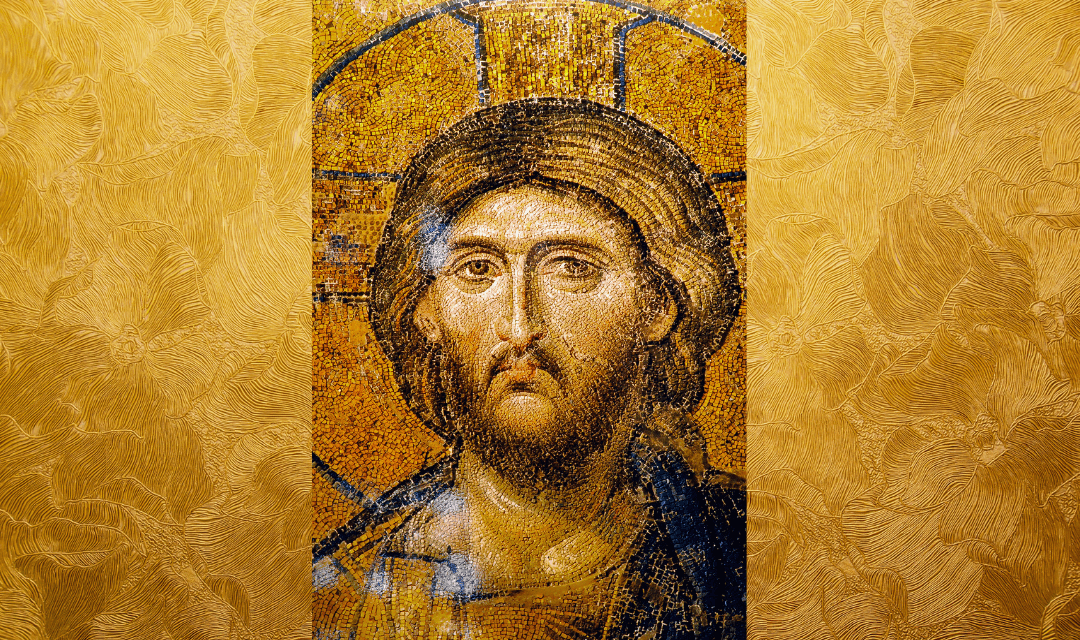

Butler opens the book with a brief introduction to the idea of seeing iconically, so brief in fact that it can be summed up in two sentences: “Historically, icons were not meant to be looked at, so much as to be looked through. They pointed to something beyond themselves” (emphasis in original).13 He illustrates his point with the famous Christ Pantocrator icon, and then applies this approach to the “profound mystery” of marital one flesh sexual union, which God designed to point to Christ and the church (Eph. 5:30–32). “The love of God is the endgame of this book,” Butler writes, “for it is what the icon points to…So, let’s pull back the veil on the icon. Like gazing through Christ Pantocrator, our ultimate goal is a fresh vision of Jesus.”14

That’s all we get when it comes to iconography and its place in Christianity. A religious practice that has obtained for nearly two thousand years in the Eastern church, a practice that lies at the very heart of Eastern Orthodox liturgy and theology, so central to their faith and to the dogma of the Incarnation that many have been martyred in its defense — this iconic worldview is detached from its complex meaning and history, and is borrowed as a premise for a book written within and for a Reformed evangelical subculture that is iconoclastic. Iconic thought and practice is largely alien to evangelicalism and to the Reformed tradition, and yet Butler brings it in the front door without commenting on the oddity (or the implications) of such a pairing.

I write this as someone who has studied iconography and the Eastern Orthodox symbolic perspective for years, and who has icons in her home (including the Christ Pantocrator). I write this as someone who recently converted from evangelicalism to an older Christian tradition after having my faith rearranged by the iconography of the patristic church. Once I started seeing through icons to the glory, I couldn’t stop. I want to say to Butler: one does not simply borrow an icon to make a point and write a book. Iconography comes with some serious strings attached — liturgical, sacramental, ecclesial, theological, moral, and Marian strings.

You may bring a painted icon into your house assuming it will function like wall decor; you may bring a Scripturally typological icon into your mind (like Beautiful Union offers), assuming it will function like a neat thought experiment. But sacred art and iconic thought are not spectator sports. You may be surprised to find iconography rather more like that painting of a ship on Eustace Scrubb’s wall in C. S. Lewis’s The Voyage of the Dawn Treader (1952). It can draw you into the gospel story as a participant instead of an observer: you’re going to get wet, and you’d better learn how to swim.

Everything about Christian traditions (Protestant and Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox) that focuses on liturgy and church tradition — from the architecture of the church to the icons on the walls, from the sacraments and prayers to the liturgy and hymns, from the Scripture readings and the incense to the kneeling, bowing, genuflecting, and processing — is structured like a microcosm of reality that is anything but arbitrary. It is designed not merely to point you to heaven but to transport you there. In this light, iconoclasm is the safest (and driest) option for the modern person, as Eustace, who wanted to “smash the rotten thing,”15 intuited: you maintain more control, and you’re less likely to get dragged into an arduous spiritual adventure, if the walls are bare.

Iconography has a theological coherence to it, a symbolic grammar, in which each part of an icon is connected to every other part, and every icon is in conversation with a host of others. Icons exist in relation to time (the liturgical calendar and church history) as well as space (church architecture and the placement of icons within the church). Just as a verbal language is composed of an alphabet, words, sentences, grammar and syntax, paragraphs, and an overarching meaning, so do all the parts and wholes of iconography fit together and live within the church’s liturgical worship, theological tradition, and biblical interpretation.

While it’s possible to extract and adopt a single word from another language into your lexicon, such as entrepreneur or karaoke, it’s quite another thing to become fluent. Fluency entails a new perspective on the world and participation in a different culture: you become a new person in relation to a living tradition. It’s the difference between trying something on for size and letting something rearrange you from the inside out.

The use of “sex as icon” that Butler utilizes in Beautiful Union is closer to the karaoke kind of borrowing than it is to cultural-linguistic immersion, and this will necessarily be the case for any non-liturgical evangelical who adopts a portion of the iconic perspective without being adopted into the tradition itself. Butler is bringing an icon to evangelicals for them to try out, but his audience is still recovering from the disturbing memory of Mark Driscoll’s salacious sermons on Song of Solomon (the last time a young, restless, and Reformed pastor encouraged us to think a lot about sex, and we all know how that went16).

Because he’s coming from the outside, Butler can’t immerse the imaginations of others into this language and culture in the manner of someone like Eastern Orthodox icon carver and symbolic thinker Jonathan Pageau, whose work I highly recommend.17 Dabbling in iconic thought without living it liturgically and sacramentally is bound to result in misconceptions, both for Butler and for his readers. Iconic thought is a package deal.

THE MISTRUST OF METAPHOR

To “get” the iconic perspective, you’ve got to be game. That implies trust — trust that the world can convey heavenly realities, and that our human intuitions can pick up on them. While describing the way that the family is an icon of the Trinity, Butler writes, “This works, of course, by analogy. God is not the same thing as a literal human family….There are differences. Yet while God is not exactly like a human family, God has designed the family to reveal something true of himself into the world. While the things of this world cannot contain God, they can speak of him.”18

Butler is using a mode of thought that is rooted in the patristic tradition but sits somewhat awkwardly within Protestantism. He’s working analogically rather than univocally, assuming that metaphors have roots in the real and aren’t just ornamentation. A univocal perspective (uni = one, vocal = voice) assumes that reality is simpler: things just “are what they are,” which makes analogies and metaphors a dangerous game, more likely to obscure and complicate the truth than to reveal it.

Since the Reformation, Protestants have tended to hold analogical thought about God at arm’s length, worried that metaphors would limit God’s power or distort His transcendence. To some, analogies run the risk of being too fleshy, almost pagan. I noticed this hesitancy and even disgust in some of the negative reactions to Butler’s article and first chapter. Even though Butler is careful to mention the limits of analogy, he was still accused of taking it too far and describing Zeus instead of Yahweh.19

Roman Catholics and Eastern Orthodox work from a hermeneutic of beauty in which the natural world is viewed primarily through the lens of creation, and therefore nature can speak truthfully of God through the way things fit together fractally and holistically. Protestants tend to work from a hermeneutic of suspicion in which the natural world is viewed primarily through the lens of the Fall, and therefore nature’s voice and vision (and humanity’s eyes and ears) are sufficiently, perhaps even totally, corrupted.

With the Fall as the frame, we can’t trust what nature appears to be saying — we can’t distinguish the signal from the noise, the ought from the is — and therefore earthly metaphors reaching toward heaven are more likely to generate idols than icons. If earth is a window into heaven, how dirty is the glass, and how degraded is our eyesight? The fundamental question of, “How much damage did the Fall do to creation and to us?” separates Protestantism from both Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy. Butler thought he was offering something inspiring to the evangelical community, but he clearly struck a nerve. He was aiming at heaven and earth’s “beautiful union,” but many evangelicals thought he was pointing at paganism and porn.

“It is contexts, and the disposition of the mind of those who partake in them…which enable metaphors to work,” Iain McGilchrist writes about the losses associated with the birth of modernity.20 “There are obvious continuities between the Reformation and the Enlightenment,” he continues. “They share the same marks of [the brain’s] left-hemisphere domination: the banishment of wonder; the triumph of the explicit, and, with it, mistrust of metaphor; alienation from the embodied world of the flesh, and a consequent cerebralisation of life and experience.”21

Metaphorical thought presumes a world saturated with layers of meaning, a “thick” world in which one thing can be itself and a symbol of something else at the same time. It was the world that existed before “just,” “only,” and “nothing but” became our adverbs of choice. The simplified world clean-shaven by Occam’s razor, disenchanted by skepticism, and demythologized by science lacks the context and disposition necessary to make metaphors work. Our cultural default when it comes to perceiving sex is pornographic (seeing mechanics without meaning, looking at rather than through) even if we don’t look at pornography ourselves.

The assumed thinness of meaning (“it’s just sex”) came up in the words of Butler’s critics who accused him of “over-spiritualizing” sex. They saw him as artificially adding something on top of a simple human experience. It looks to me like Christians have been under-spiritualizing sex (and just about everything else) for a very long time. In the words of Pageau,

It feels like a lot of modern Christians have a materialist worldview, basically, and on top of this materialist worldview they kind of slap on a story of God who became man and was crucified on the cross, but sometimes that doesn’t jive together very well. Whereas what I was discovering in the art and in this whole way of living [the liturgical life of the Eastern Orthodox Church] was a way for Christianity to become the lens by which I look at the world, rather than putting a story on top of a scientific materialist lens. (Emphasis added.)22

In other words, icons are the lenses of a liturgically livable worldview, a way to see the world with the categories and metaphors the Bible provides. Butler’s enthusiasm for the iconic was extracted from a historical tradition and abstracted from embodied sacramentality. He borrowed a part while eschewing the whole, and in doing so revealed that the part can’t stand on its own, but will be (in fact, was) misunderstood and rejected by much of his evangelical audience.

THE ICONIC WORLDVIEW IS ETHICALLY CHARGED

The benefit of living in a “thin” non-iconic world is that you have more freedom to interpret things as you see fit. To go from the wide-open fields of evangelical adiaphora, in which Christian liberty leaves much of morality and practice open to personal judgment, into the recognition that the world has a revelatory nature is quite the shock. To discover that the physical has a metaphysical grain to it, and that materiality is preloaded with a spiritual structure we call symbolism (the same symbolic structure that lives in Scripture, church architecture, icons, and traditional liturgies), can be unsettling.

It’s unsettling because the more you see, the more is required of you morally. The field of personal preference and individual autonomy shrinks as the iconic vision grows. The beauty of this vision is simultaneously ethical, a point Butler makes repeatedly in Beautiful Union. God’s rules about sex aren’t arbitrary: no adultery, no divorce, no premarital sex, no promiscuity, no gay sex, no porn, no rape, no coercion, no masturbation, no prostitution, no bestiality, no abortion, no permanently contracepted sex — these are the contours of a picture. Sin isn’t just rule-breaking; it’s iconoclasm. To commit sexual sin is to lie with your body about the nature of God.

Iconic thought reveals the inseparability of belief and practice. For Protestant traditions that draw a hard line between justification and sanctification, that’s a problem. But for traditions that envision salvation as the process of theosis or divinization — God became man that man might become God — drawing a hard line between saved and sanctified is a false dichotomy. These are questions every Christian has to face: Is the holiness of creation an impossibility in this life? Or at best a nice, hoped-for side effect after one “gets saved”? Or is participation in God’s holy divine nature the very definition of being saved?

Within Eastern Orthodoxy, an icon is a sacred image of a holy person. It’s not a naturalistic portrait: “Since the person depicted is a bearer of divine grace, the icon must portray his holiness to us.”23 Anyone can see bodies and historical realities, but that is not the same thing as perceiving holiness in and through the image, or recognizing the living grace of the prototype behind the icon. Jesus is “the image [eikōn] of the invisible God” (Col. 1:15 ESV), and yet many who saw Him in the flesh didn’t see the Father through Him; they saw instead only a man to be crucified and spat upon. We are all capable of looking with secular eyes at a holy person or at a holy reality, of looking at instead of looking through, in Butler’s words. Some things require a holy faith to properly perceive: “Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God” (Matt. 5:8 ESV).

To see iconically is to adopt a perspective in which people and things can become holy in lived experience (not solely by God’s declaration), can participate in the divine nature, and can bear the glory of God now, in this life (2 Pet. 1:3-8). Iconic thought is tied to the hierarchy of saints: once we admit the possibility that people can participate in God, then it becomes clear that some let the light shine through better than others do. As Leonid Ouspensky writes in Theology of the Icon, “There is, therefore, an organic link between the veneration of saints and that of the icons. This is why in a theology that has removed the veneration of saints (Protestantism), the sacred image no longer exists.”24

Holy icons and holy people go together: if you don’t believe that sainthood is possible in this life, then icons won’t fit within your theology. The iconic worldview is ethically charged in a way that is foreign to evangelicalism with its emphasis on Christian liberty; it’s also foreign to Reformed theology with its emphasis on total depravity, the bondage of the will, and the sense that any good we do is just “filthy rags.” As I said at the start, one does not simply borrow an icon, because iconography and the theology that supports it are fundamentally at odds with evangelical and Reformed views of creation, the Fall, salvation, and sanctification. Suspicion of the perfectibility of human nature is also behind the downgrading of Mary within Protestantism, which comes with its own set of consequences.

MISSING THE MODESTY OF THE MOTHER OF GOD

In Women and the Gender of God, Amy Peeler writes, “Without birth through a woman, Jesus of Nazareth did not live. The title ‘Mother of God’ is the indispensable prolegomena to the gospel. If she is forgotten, the whole theological project goes askew. Protestants, particularly those in nonliturgical traditions, have a great deal to learn from our brothers and sisters who never lost their connection to the ancient and healthy Marian piety.”25

Beautiful Union suffers from this lost connection to Marian piety. For a book that is exploring the fruitful union of God’s marriage to His people, and that examines the symbolism of the female body and womb as an iconic sacred space that hosts the presence of God, it is an inexcusable oversight that Butler fails to unpack the meaning of Mary’s miraculous pregnancy with the incarnate Savior. Butler uses symbolic language that the early and medieval church used for Mary’s special role, but he fails to conclude that she is the consummation of all of that typology. He gives the first Eve plenty of mentions, but the “second Eve” (as St. Irenaeus called her) gets only three, all of which are brief throw-away lines. He makes Mary peripheral. I went back and counted the number of times I furiously scribbled, “Where is MARY!?” in the margins where the typology was left dangling: sixteen.

Neglecting Mary in this context is so egregious not only because the church fathers have given us ample exposure to this perspective — she bore Him whom the heavens could not contain (Augustine), she is the Ark of the New Covenant (Athanasius) as well as the throne of the King, the tabernacle of God the Word, and the greater holy of holies (Romanos) — but because Mary was a virgin and the pinnacle of modesty. Her virginal conception of Christ tempers and transforms the narrative about the iconicity of sexual union, clearly showing the limits of the analogy (God does not have sex with Mary). She who was closest to Christ and His first disciple, she who treasured all these things up in her heart (Luke 2:19), she who lived with Him daily for thirty years, never wrote down the good news. She carried, bore, nursed, and raised the Good News bodily instead, an implicit rather than an explicit testimony — which exemplifies the “veiledness” and privacy proper to the mystery.

While Butler opens with an invitation to “pull back the veil on the icon,”26 a Marian, feminine sensibility would have known just how much to show and how much to hide. The fact that so many women felt grossed out27 or violated by Butler’s language is not an indication of prudery, but of the fact that he needed to use more robust euphemisms with greater delicacy (which he has since come to admit28). Sex can be perceived as an icon of the union of heaven and earth without causing offense, but only if guided by a spirit of modest Marian piety, as it is in Eastern Orthodoxy and in much of Catholicism29 — that’s a connection few evangelicals would notice, and a concession even fewer would be willing to make. Mary too has suffered the fate of Occam’s adverbs: she is, after all, “just a girl.” Butler’s explicit “unveiling” language for which his critics took him to task reveals yet another way in which borrowing an iconic perspective out of the context in which it was originally embedded (its Marian context) can lead to harm. If you want to go “full icon,” you’d best bring Mother Mary with you.

THE PROBLEM OF “PASSIVITY” AND THE ICON OF RAPE

The evangelical mistrust of metaphor, lack of liturgy and Marian piety, and views on the limits of human holiness, all contributed to problems both within Beautiful Union and in the angry response to it. But there’s more, and this may be the darkest issue of all: the charge that Butler was describing women as sexually passive, as mere semen receptacles whose participation, pleasure, and even consent isn’t valuable, which paves the way for a theological justification of abuse.30 Butler goes to great lengths in his book to deny that this is what his ideas imply when he deals with the “tragic inversion” of an icon that is meant to convey love: “Rape (and all forms of sexual violence, abuse, or exploitation) turns giving of the self into taking for the self. It converts generosity into a form of theft….Sexual violence and abuse shatter the icon of sex in the most despicable way….Sexual assault violates the safety, beauty, and faithfulness sex is designed for in marriage, turning the beautiful into something brutal, intimacy into invasion.”31

People who were already critics of TGC’s complementarian approach and Reformed theology took the opportunity of Butler’s article to connect the dots in a way that Butler himself explicitly disavows. He repudiates a “just lie there and take it” theology of “grace” that annihilates agency rather than activates it. But in doing so, he distances himself from some big names within the Reformed tradition.

Theologian Louis Berkhof defined regeneration as “a work in which man is purely passive, and in which there is no place for human co-operation” (emphasis in original).32 A strictly monergistic work of God is one in which the human subject can neither cooperate nor resist. Being “born again” and united to Christ is, in this framing, something God does to and for us (rather than with us), while we “receive” it. It’s a way of framing receptivity not as a participatory action in its own right (as is proper to persons), but as what an object has done to it by a “real” agent. As Calvin wrote in the Institutes, “Any intermixture which men attempt to make by conjoining the effort of their own will with divine grace is corruption, just as when unwholesome and muddy water is used to dilute wine.”33 The freely given consent and fruitfulness of the feminine partner (creation, the church, the Bride, the believer) is framed as a contamination, an attempt at earning salvation. The dynamic of Creator and creation is recast as a competition between agencies, as a matter of authority and submission, activity and passivity, rather than a mutual participatory union of love.

And this is where Reformed theology gets into trouble with marital sex as iconography. Reformed pastor and theologian Douglas Wilson says the quiet part out loud: “[T]he sexual act cannot be made into an egalitarian pleasuring party. A man penetrates, conquers, colonizes, plants. A woman receives, surrenders, accepts….True authority and true submission are therefore an erotic necessity” (emphasis in original).34

Reciprocally loving sex in a good marriage resonates iconically with a picture of salvation as synergism — mutual participation between God and humanity. But salvation as monergism — in which God does everything, and humanity does nothing to participate — doesn’t look like grace. It looks like rape. Reformed theologian R. C. Sproul said as much. “You will resist it as hard as you can. But God will overcome your resistance….When God chooses to save somebody, in his sovereignty, he saves them. [Jonathan] Edwards called it ‘the holy rape of the soul.’ Some people are violently offended by that language. I think it’s the most graphic and descriptive term I can think of, of how I was redeemed.”35

If the combination of “marital sex as icon” with Reformed soteriology creates an icon of rape, the problem isn’t with the icon, it’s with a theology that prefers a contest of wills rather than a relationship. According to Pope Benedict XVI, the monergistic theology of the Reformers has triggered a justified modern-day outcry:

An exaggerated solus Christus [Christ alone] compelled its adherents to reject any cooperation of the creature, any independent significance of its response, as a betrayal of the greatness of grace. Consequently, there could be nothing meaningful in the feminine line of the Bible stretching from Eve to Mary. Patristic and medieval reflections on that line were, with implacable logic, branded as a recrudescence of paganism, as treason against the uniqueness of the Redeemer. Today’s radical feminisms have to be understood as the long-repressed explosion of indignation against this sort of one-sided reading of Scripture.36

The iconic perspective Butler champions actually exposes monergism as coercive, undercutting its theological credibility, which is why I’m surprised to see a book like Beautiful Union come from (and speak to) a Reformed subculture. I don’t know if Butler realizes that this symbolism saws off the Reformed branch on which he sits (his decision to include the old problematic language of “active” male and “passive” female undercut his discussion of mutuality and reciprocity, which made the chapter one section on “The Nature of Grace” sound deeply confused37).

If “rape corrupts the character of the icon,” as he claims,38 then a theology that lets God symbolically get away with something that no Christian would ever countenance on the human level has some explaining to do — either that, or ditch the iconic perspective that is causing all the trouble and instead stake your claim on the discontinuity of heaven and earth. No wonder Calvin was an iconoclast: he had priors to maintain. John Donne may plead, “Batter my heart, three-person’d God…and bend Your force to break, blow, burn,”39 but I have my doubts that a woman would write such words. Rather than the battering ram of irresistible grace, the sound our hearts should be listening for is that silent and not-yet-pregnant pause (as heaven and earth held their breath) just before Mary spoke: “Behold, I am the servant of the Lord; let it be to me according to your word” (Luke 1:38 ESV). In that silence and space is our freedom, our dignity, our consent, and our participation, for we are all invited to be Marian, to enter into communion with Mary’s “Yes.”

CURIOSITY ABOUT THE FRAME

Protestants have every reason to raise their eyebrows over Butler’s book — not because he’s singing an ode to the male orgasm (he’s not); not because he’s a sexist oblivious to women’s equal dignity and value (he isn’t); not because he’s excluding the experiences of single, celibate, abused, gay, or infertile people (couldn’t be further from the truth). Reading the book in its entirety should address the worst of the reactions generated by the article alone and make it clear that Pastor Josh is a good man with good intentions. If he receives pushback, it should come in the form of a charitable argument, not a sneer (or a Tweet, though perhaps those are the same thing).

The deeper reason Protestants have to be skeptical of Beautiful Union is because Butler is introducing readers to a strain of patristic and Neoplatonic thought that, if found to be intellectually compelling, might lead them into an older tradition where iconography is a live liturgical reality and not just a provocative thought experiment.

On the other hand, it’s equally possible that Butler’s icon tourism will turn some readers away from iconic thought, because his enthusiasm outstripped his prudence. It’s hard to dissuade a person out of their initial reaction of disgust and outrage, especially if they’ve already committed by joining a social media dogpile. First impressions seldom give way to second thoughts in the Twitter-verse. And, despite the irony involved, public scapegoating (of the kind Butler endured) has its own special pleasures and social functions that are hard to resist, even for Christians.

Where many see Butler and TGC as the source of the problem, I think it’s more accurate to include the critics in the mix too and describe what happened as a botched evangelical effort at engaging larger metaphysical categories and symbolic mysteries that the community desperately needs. But lacking the experience with (and disposition for) a metaphorical approach to theology, lacking the liturgy to give such metaphors a place to land, lacking the holy privacy of Mary’s heart to mitigate the American tendency to “let it all hang out,” what could have been a fruitful exploration is instead at risk of dying on the vine.

For those willing to go beyond judging a book by its first chapter, Beautiful Union is worth a second look, and a deeper one — not because every single thing in it is inarguably true (by all means, let’s argue), but because the negative reaction to the article was so swift and explosive, and this speaks volumes about the context in which it dropped, the frame in which it was viewed.

Every follower of Christ will benefit from stepping back and looking not just at the faith that they have received, but also the manner in which that faith is framed. It’s impossible to see and know everything, everywhere, all at once: we all frame reality (Christianity included) to shrink it down to a manageable size, and this makes certain things obvious, and other things invisible. So whether you agree with Beautiful Union or not, the ancient and poetic vision it’s reaching for will make you aware of your own vision and its limitations. And if you’re willing to be curious about that, you might find that venturing into a new frame has the potential (as it did for Eustace) to begin to make you into a different kind of person.

Alisa Ruddell is a staff writer and associate editor for the online magazine Christ and Pop Culture and has previously published at Salt and Iron.

NOTES

- Jen Pollock Michel, Amazon.com editorial reviews/book endorsement for Beautiful Union by Joshua Ryan Butler, https://www.amazon.com/Beautiful-Union-Unlocks-Explains-Everything/dp/0593445031/.

- Brett McCracken, Amazon.com editorial reviews/book endorsement for Beautiful Union by Joshua Ryan Butler, https://www.amazon.com/Beautiful-Union-Unlocks-Explains-Everything/dp/0593445031/.

- Erin Martine Hutton, “Pornifying the Sacred: How the Song of Songs Can Help Counteract Gender Inequality and Domestic Abuse,” ABC Religion & Ethics, March 9, 2023, https://www.abc.net.au/religion/sacramentalising-sex-can-lead-to-rationalising-abuse/102077030.

- Beth Felker Jones, “Protestant Bodies, Protestant Bedrooms, and Our Need for a Theology Thereof,” Church Blogmatics, March 4, 2023, comment section, March 17, 2023, https://bethfelkerjones.substack.com/p/protestant-bodies-protestant-bedrooms.

- Felker Jones, “Protestant Bodies,” https://bethfelkerjones.substack.com/p/protestant-bodies-protestant-bedrooms.

- Joshua Ryan Butler, Beautiful Union: How God’s Vision for Sex Points Us to the Good, Unlocks the True, and (Sort of) Explains Everything (Colorado Springs, CO: Multnomah, 2023).

- Editors’ note: The original post is accessible via the Internet Archive: Josh Butler, “Sex Won’t Save You (But It Points to the One Who Will),” The Keller Center, TGC, March 1, 2023, Internet Archive, March 1, 2023, https://web.archive.org/web/20230301224954/https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/article/sex-wont-save-you/.

- Jessica Lea, “Joshua Butler Resigns as Pastor Following Controversy over Book about ‘God’s Vision for Sex,’” Church Leaders, May 4, 2023. https://churchleaders.com/news/450492-joshua-ryan-butler-resigns-pastor-gods-vision-sex.html.

- Butler, Beautiful Union, 15.

- Butler, Beautiful Union, 22.

- Mere Fidelity: A Podcast from Mere Orthodoxy, “Beautiful Union, with Joshua Ryan Butler,” May 2, 2023, https://merefidelity.com/podcast/beautiful-union-with-joshua-ryan-butler/.

- Although the following article is a book review of a biography of Pastor Timothy Keller, there is an in-depth treatise on the meaning of the term “Reformed”: Kevin DeYoung, “An American Evangelist (A Review of Timothy Keller: His Spiritual and Intellectual Formation by Colin Hanson),” First Things, May 2023, https://www.firstthings.com/article/2023/05/an-american-evangelist.

- Butler, Beautiful Union, xi.

- Butler, Beautiful Union, xv.

- C. S. Lewis, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader (1952; UK: HarperCollins, 2000), 10.

- Mike Cosper, “The Things We Do to Women,” The Rise and Fall of Mars Hill, CT, July 26, 2021, https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/podcasts/rise-and-fall-of-mars-hill/mars-hill-mark-driscoll-podcast-things-we-do-women.html.

- Alisa Ruddell, “It’s a Festival, Not a Machine: Celebrating The Symbolic World,” Christ and Pop Culture, August 25, 2020, https://christandpopculture.com/its-a-festival-not-a-machine-celebrating-the-symbolic-world/.

- Butler, Beautiful Union, 40.

- Felker Jones, “Protestant Bodies,” https://bethfelkerjones.substack.com/p/protestant-bodies-protestant-bedrooms.

- Iain McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World, 2nd ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), 317.

- McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary, 337.

- Jonathan Pageau, “Icons Are Not Just Decor, They Are about Worldview | The Importance of Imagery (Gospel Simplicity),” Jonathan Pageau — Clips, YouTube, August 26, 2021, video, 6:41, https://youtu.be/l2xTHd9YJpw.

- Leonid Ouspensky, Theology of the Icon, Vol. 1 (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1992), 171.

- Ouspensky, Theology of the Icon, Vol. 1, 166.

- Amy Peeler, Women and the Gender of God (Grand Rapids: MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2022), Kindle version, Introduction, paragraph 9.

- Butler, Beautiful Union, xv.

- Beth Moore (@BethMooreLPM), Twitter, April 18, 2023, 6:30 p.m., https://twitter.com/BethMooreLPM/status/1648453892215304195.

- See Butler’s resignation letter for his apology over a lack of pastoral nuance, posted at Ben Marsh (@PastorBenMarsh), Twitter, May 3, 2023, 4:07 p.m., https://twitter.com/PastorBenMarsh/status/1653853916239388673.

- David L. Schindler, “Christopher West’s Theology of the Body,” Catechism.cc, February 25, 2018, https://www.catechism.cc/articles/David-Schindler-Christopher-West.htm.

- Felker Jones, “Protestant Bodies,” https://bethfelkerjones.substack.com/p/protestant-bodies-protestant-bedrooms.

- Butler, Beautiful Union, 11.

- Louis Berkhof, Systematic Theology (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1996), 465.

- John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, trans. Henry Beveridge (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2008), 208.

- Douglas Wilson, Fidelity: How to Be a One-Woman Man, 2nd ed. (Moscow, ID: Canon Press, 2012), 88–9.

- R. C. Sproul, “Divine Sovereignty and Man’s Helplessness,” 3rd Lecture in a series of four, at The Falls Church, Falls Church, Virginia, c. 1996, in “Dr. R. C. Sproul — ‘Holy Rape of the Soul’ Analogy (Audio) — Posted for Educational Purposes Only,” J. K. Jenkins, YouTube, video, 0:30, December 5, 2021, https://youtu.be/eQwSC3Dx1Zk.

- Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger and Hans Urs von Balthasar, Mary: The Church at the Source, trans. Adrian Walker (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2005), 43.

- Butler, Beautiful Union, 12–14.

- Butler, Beautiful Union, 10.

- John Donne, “Holy Sonnets: Batter My Heart, Three-Person’d God” (1633), Poetry Foundation, accessed May 19, 2023, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44106/holy-sonnets-batter-my-heart-three-persond-god.