Listen to this article (12:44 min)

Cultural Apologetics Column

The following article appeared as an online-exclusive in CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL, volume 48, number 02 (2025).

When you support the Journal, you join the team and help provide the resources at equip.org that minister to people worldwide. These resources include our ever-growing database of more than 2,500 articles and Bible Answers, as well as our free Postmodern Realities podcast.

Another way you can support our online articles is by leaving us a tip. A tip is just a small amount, like $3, $5, or $10, which is the cost of a latte, lunch out, or coffee drink. To leave a tip, click here.

[Editor’s Note: This review contains spoilers for Assassin’s Creed Shadows.]

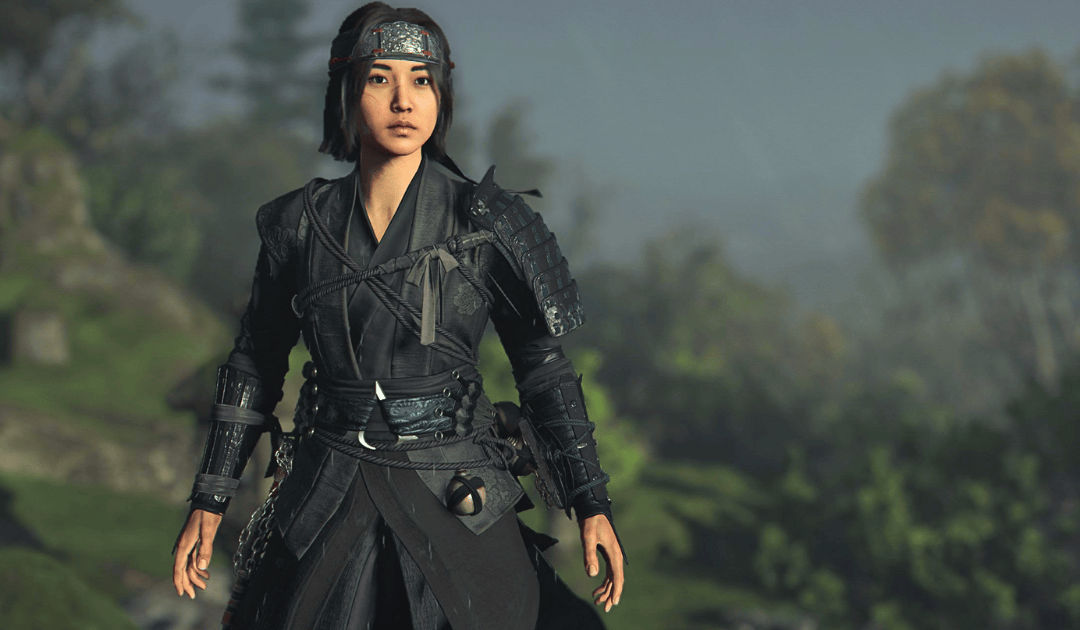

Assassin’s Creed Shadows

Developed by Ubisoft Quebec

Published by Ubisoft

Directed by Jonathan Dumont and Charles Benoit

Written by Ryan Galletta

Produced by Karl Onnée

Released 2025

ESRB Rating: Mature 17+ for Blood and Gore, Intense Violence, Language

The release of Assassin’s Creed Shadows (2025) marked a long-anticipated leap into feudal Japan for Ubisoft’s flagship video game franchise. Set in the late Sengoku period (16th century) — a time of political unrest and complexity for the nation — the game invites players to embody both a shinobi (ninja) assassin and an honorable samurai. But somewhere beneath the flowing robes and layered armor and the series’ trademark intrigue lies a cultural and religious worldview that is largely unfamiliar to many Westerners: Shintoism.

As with previous entries in the series, Shadows is more than willing to let players explore its detailed recreation of historical Japan and give players glimpses of the routines and rituals of daily life. One mission, for example, revolves around Naoe (the shinobi) learning the intricacies of a formal tea ceremony. Shrines dot the sweeping landscapes along with the iconic torii gates. At the temples players can visit at will, non-playable characters carry out purification rites and revere both ancestors and kami (divine spirits). All these things contribute to the game’s cultural texture. And for discerning Christians players, this opens a door to conversations about faith and its portrayal in video games.1

How should Christians engage with portrayals of spiritual systems like Shintoism in popular media? What does it mean to interact with a world where the divine is in the wind, the mountain, and the sword? And what can cultural apologetics offer in response? These are the questions we will explore while unpacking the theological implications of Shintoism, considering how Christian gamers can thoughtfully and faithfully navigate the spiritual imagination of another culture without losing sight of the gospel.

Exploring Genetic Memories. Since its debut in 2007, Assassin’s Creed has built its reputation on a unique mixture of stealth gameplay and historical settings. In an interview with The Guardian, series architect Patrice Désilets explained how the team at Ubisoft landed on their core template:

A book called Alamut was an influence. Though this book is a fictional work, it’s based on the Historical Clan of Assassins and it prompted the team who were passing the book around to do further research about the Assassins and their time period — the 3rd Crusade. The more we discovered about these people, the more we wanted to make a game about them.2

But all of this has been framed by a singular ambitious narrative conceit: what if humans could, via advanced technology, relive the memories of ancestors locked within DNA? At the heart of the series is the Animus, a fictional machine that allows modern humans to access the genetic memories stored within their own bloodline. Through this device, players inhabit the lives of assassins across different periods of history — Jerusalem during the Crusades (Assassin’s Creed [2007]), Renaissance Italy (Assassin’s Creed II [2009]; Assassin’s Creed: Brotherhood [2010]), Constantinople under the Ottoman Empire (Assassin’s Creed: Revelations [2011]), the American frontier (Assassin’s Creed III [2012]; Assassin’s Creed Rogue [2014]), the Caribbean during the Golden Age of Piracy (Assassin’s Creed IV: Black Flag [2013]), Ptolemaic Egypt (Assassin’s Creed Origins [2017]), ancient Greece (Assassin’s Creed Odyssey [2018]), Viking England (Assassin’s Creed Valhalla [2020]), and the Abbasid Caliphate (Assassin’s Creed Mirage [2023]).

Each game is thus a dual narrative (to one degree or another): one set in the past, and one in a modern or near-future setting, where a secret war rages between the Assassins and the Templars, and their precursor organizations, the Hidden Ones and the Order of the Ancients. “The conflict between the Assassins and the Templars is largely ideological,” explains Caitlin Grieve, writing for ScreenRant. “The Templars believe that a perfect, happy utopia can only be established under extreme rule and order….The Assassins, on the other hand, prize free will above all else.”3 From the beginning, Assassin’s Creed has largely been a series of contrasts: free will versus determinism, truth versus power, and similar conceits.

But the series has also wrestled with religions — sometimes clumsily, sometimes with surprising nuance — by portraying Christianity, Islam, Greco-Roman paganism, and ancient Egyptian beliefs as part of the experiences of its historical characters. Yet the series is not neutral and often presents organized religion — especially monotheism — as a tool of control, subtly aligning itself with a kind of post-Enlightenment skepticism. Its overarching mythology, involving precursor races and false gods, offers a secular mythos meant to explain away the supernatural.

This mythos revolves around the Isu, an advanced, pre-human civilization whose members were once worshiped as gods by early mankind. Possessing immense technological knowledge and near-immortality, the Isu created humanity to serve them, encoding obedience directly into the human genome. This race of beings includes figures who are later remembered in human myths, like Minervo, Juno, and Jupiter, among others, drawing from many different and well-known mythologies across the series. Some of the “Pieces of Eden” (Isu weapons and artifacts from tens of thousands of years ago) were created to allow for instantaneous and total mind control to keep humanity enslaved. But a conflict between humans and the Isu broke out when two humans, Adam and Eve, stole the Apple of Eden and started a rebellion. The Isu were eventually destroyed in a global catastrophe, leaving behind fragments of their technology, which Order of the Ancients (and later the Templars) seek to recover in order to construct a utopia. The Hidden Ones (and later the Assassins) are those who seek to prevent the Order from recovering the fragments and thereby enslave humanity all over again.4

Shadows and Shinto. In Shadows, the usual Assassin’s Creed formula is applied to Japan. But unlike previous entries in the series, which has dealt largely with Western systems of thought, the theological conversation shifts. Instead of confronting institutional religion or Scriptural revelation, the game steps into a world shaped by Shinto — a tradition without a central founder, sacred text, or systemized theology. Instead, it is built on ritual and one’s relationship with the natural and spiritual worlds. For Christian players, the implications are different here than they were in, say, Assassin’s Creed: Brotherhood (2010). The question is no longer “What does the game say about the Church?” but “What does the game say about the sacred?”

Shinto, often translated as “the way of the gods,” is less a codified system of belief than it is a posture toward the world — a way of living in harmony with the unseen forces that dwell within it. In contrast to religions grounded in revelation and tabulated in doctrinal statements, Shinto is a deeply relational and ritualistic tradition that is rooted in the localized, communal practices tied to the land, ancestors, and nature.5

Before the arrival of Buddhism in Japan, there were “many local cults that are nowadays grouped under the name Shinto.”6 The focal points of worship for these local cults were the kami — a term often translated as “gods” or “spirits,” but which might be better understood as presences. A kami might be a mountain, a river, a tree, a storm, or an ancestor’s spirit, with many kami looked upon as the ancient ancestors of whole clans. If a person was particularly virtuous, such as the Emperor, they could become kami upon their death.7 Human beings do not worship the kami in the sense of surrendering to a sovereign deity; rather, they honor, appease, and coexist with them through ritual. Another important aspect of Shinto closely linked with kami is musubi. Explaining this concept, Boy and Williams write:

Humans, like all aspects of nature, are manifestations of a life-giving power, a generative, creative force that is the basis of all life. The Shintō term for this creative principle permeating all forms of life is musubi. This term also carries the connotations of “combination,” “joining,” and “binding together.” Thus, musubi refers to the harmoniously creating and connecting force that manifests itself in all of Great Nature.8

This makes Shinto a religion of proximity, not necessarily transcendence. There is no ultimate Creator-God in the biblical sense. Instead, divinity is diffused across creation and woven naturally into the mundane. Purification rituals (misogi), shrine visits, seasonal festivals, and offerings are traditions, yes, but they are also quite literally how one keeps balance with the “spiritual order” of things. Eventually Buddhism entered Japan during the sixth century, and most of the schools of Japanese Buddhism were established during the Kamakura period (1185–1333). Citing Kuroda Toshio’s scholarship, Mark Teeuwen and Bernhard Scheid point out that “until at least the Kamakura period, the word Shinto was used not to refer to a ‘popular religion’ by that name, but more or less as a synonym for kami.”9

In the context of Assassin’s Creed Shadows and its recreation of Sengoku Japan, Shintoism is woven into the game’s architecture and mechanics, with shrines serving as points of meditation and reflection that offer perks or bonuses. Certain missions focus on rituals, such as the quest in which Yasuke must go through the stages of purification before the story will continue. Others require Naoe to meditate and reflect in order to unlock playable sections that flesh out her backstory.

For Christian players, these sections of gameplay can present some interesting moments for reflection. In a world where sacred space is not defined by holiness so much as it is by closeness and continuity, how does one articulate a vision of God who is both transcendent and near? How does one distinguish between creation as sacred and the sacredness of the Creator?

Immanent Longing. In a world like the one presented in Shadows, where sacred space is diffused across creation, spiritual longing is quite palpable. Shintoism captures this longing in its own way, recognizing that there is more to reality than what can be measured. The ritualism, the attentiveness to nature, and the deep sense of respect for those who came before all point to a profound awareness that life is not merely biological — it is, in point of fact, spiritual.

As Christians, we recognize that this immanent sense of the sacred — what the apostle Paul might liken to the impulse to “grope for Him and find Him” (Acts 17:27)10 — was never meant to terminate with and in nature itself. For the biblicist, creation is not the end of the story, but the beginning of revelation. The heavens declare the glory of God (Psalm 19), but they do not contain Him. And that longing for connection with the unseen worlds finds its fulfillment not in kami or musubi, but in Christ, “the image of the invisible God” (Colossians 1:15).

For Christian players, Assassin’s Creed Shadows offers a moment to reflect on what it means to live in a world that aches for the sacred and goes looking for sacred space. It invites one to consider how the gospel is the unique balm to be applied to that particular pain not by denying the spiritual reality that Shinto seems to gesture toward, but by fulfilling it in the One who is both transcendent and immanent, holy and near, as Paul points out in the latter half of Acts 17:27: “He is not far from each one of us.”

And this is the work of cultural apologetics: not to sneer, nor to try and baptize other systems of belief uncritically, not to foist “evidence” upon another in a tit-for-tat approach to see who is “more right.” But to simply trace the patterns of human longing and show how they find their shape in Christ. It means engaging thoughtfully with media like Assassin’s Creed Shadows as both entertainment and a cultural artifact that reveals how people imagine the divine and order their world accordingly and seek meaning and purpose within it. Where Shinto offers a vision of sacred presence woven into the fabric of creation itself, the gospel of Jesus Christ offers the presence of a personal God who entered that world not as a fickle spirit to be appeased, but as a Savior who came to redeem it.

So, when passing through the torii gates or climbing the long steps leading to a shrine, players can see in Assassin’s Creed Shadows the little signs of a world still reaching for its creator. And it is the Christian’s unique position to be able to say with both confidence and compassion that He has already reached for us.

Cole Burgett is a graduate of Dallas Theological Seminary and the Moody Bible Institute. He teaches classes in systematic theology and Bible exposition and writes extensively about theology and popular culture.

NOTES

- Editor’s note: On the question of Christians and video gaming, see Kevin Schut, “Can God Fit in This Machine? Video Games and Christians,” Christian Research Journal 36, no. 03 (2013), https://www.equip.org/articles/can-god-fit-in-this-machine-video-games-and-christians/#christian-books-2; C. Wayne Mayhall, “What Price Cyberspace?,” Christian Research Journal 31, no. 06 (2008), https://www.equip.org/articles/what-price-cyberspace-/; Drew Dixon, “Summer Vacation, Kids, and Video Games: Better Alternatives to Fortnite,” Christian Research Journal 42, no. 2 (2019), https://www.equip.org/articles/summer-vacation-kids-and-video-games-better-alternatives-to-fortnite/.

- Patrice Désilets, quoted in Greg Howson, “Assassin’s Creed Interview,” The Guardian, October 19, 2007, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/gamesblog/2007/oct/19/assassinscreedinterview.

- Caitlin Grieve, “Assassin’s Creed: Why Assassins and Templars Hate Each Other,” ScreenRant, September 24, 2020, https://screenrant.com/assassins-creed-templars-conflict-free-will-medjay-ubisoft/.

- For a detailed overview of this complex mythology, see James Lynch, “Assassin’s Creed: The Full Story of the Isu,” CBR, February 6, 2022, https://www.cbr.com/assassins-creed-isu/.

- Rosemarie Bernard, “Shinto and Ecology: Practice and Orientations to Nature,” Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology (n.d.), accessed April 28, 2025, https://fore.yale.edu/World-Religions/Shinto/Overview-Essay.

- “Shinto History,” Religions, BBC, October 10, 2009, https://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/shinto/history/history_1.shtml.

- For a wider treatment of the kami in its cultural context, I recommend picking up Yoshiro Tamura, Japanese Buddhism: A Cultural History (Tokyo: Asher Publishing, 2000).

- James W. Boyd and Ron G. Williams, “Japanese Shintō: An Interpretation of a Priestly Perspective,” Philosophy East and West 55, no. 1 (2005): 34, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4487935?seq=2.

- Mark Teeuwen and Bernhard Scheid, “Tracing Shinto in the History of Kami Worship: Editors’ Introduction,” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 29, no. 3/4 (2002): 196, JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/30233721?seq=2.

- Bible quotations are from the NASB1995.