This article first appeared in the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL, volume 35, number 05 (2012). The full text of this article in PDF format can be obtained by clicking here. For further information or to subscribe to the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL go to: http://www.equip.org/christian-research-journal/

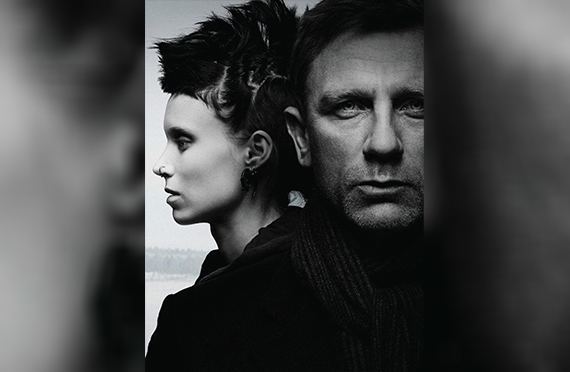

A tattooed, troubled girl who is also a brilliant computer hacker, a disgraced journalist with a passion for exposing corruption, and a complicated plot with connections that continue to unfold over three novels: all these are ingredients in the extraordinarily popular series The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, The Girl Who Played with Fire, and The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet’s Nest. The late Swedish author Stieg Larsson’s (d. 2004) Millennium Trilogy has become a worldwide hit. The books are New York Times Bestsellers, and a Hollywood adaptation of the first book appeared in 2011. Should Christians take note? Yes, but with caution.

CRIME FICTION GENRE AND MORALITY

Before considering the Millennium Trilogy specifically, we should look at its genre: the crime novel. The genre of crime fiction (or mystery) is by its nature aligned with a theistic worldview. In order to have an interesting crime novel, one must have a crime: that is, an act that both the characters and the readers acknowledge as being genuinely transgressive. If there is no moral order to the universe, there can be no such thing as crime; in an atheistic world, the idea of moral transgression is not even a coherent concept. If atheism were true, then murder, rape, or betrayal would be the equivalent of failure to get the appropriate building permit for a new business: there could be utilitarian reasons to prohibit certain acts, but there would be no moral element to the prohibition.

Crime novels generally do not center around parking tickets or building permits, but around betrayal, theft, murder, and assault, for the simple reason that readers (no matter what their conscious worldview) count on a moral component that adds significance to the story. Only if there is a transcendent moral order does it make sense for the author to expect the readers to recognize crime and condemn it and the characters who do it.

Another basic premise of a crime novel is that there is a mystery to be unraveled, in which the characters attempt to discover the truth using clues and their own powers of reasoning. This is only possible if theism is true. If natural- ism is true, then we can have no confidence in our own ability to draw conclusions from the evidence of our senses.1 If the characters (and the reader) cannot be counted on to make sense of the evidence in a real way, the idea of an investigation would be meaningless, any conclusions about the perpetrator of the crime would be unreliable, and the story would be pointless.

As a genre, then, mystery and thrillers are basically friendly to the Christian worldview. Reading through the mystery stories and novels of the nineteenth and early- twentieth centuries reinforces this view. The famous Christian apologist G. K. Chesterton wrote an entire series of mystery stories featuring Father Brown, and Christian author Dorothy Sayers wrote the classic Lord Peter Wimsey novels. Even crime novels that were not by Christian authors generally showed a strong moral sense.

However, one of the side effects of the cultural shift of the past fifty years is the constriction and deformation of the mystery genre. As fewer and fewer acts are considered genuinely wrong, the available plot points for an author of a crime novel are reduced. However, as noted above, a moral core is still necessary for the story. As a result, popular mysteries and thrillers provide a useful litmus test for what behavior is still considered transgressive and what has been accepted as normal.

A CULTURAL LITMUS TEST

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and its sequels offer a valuable glimpse deep into the secular worldview: we can observe, through the lens of the crime plot, where the line is drawn between good and evil. In these books, for instance, homosexuality is presented as perfectly acceptable; the only characters who seem to object to it are coarse bullies who hurl slurs. Adultery is presented as a nonissue. Violence is presented uncritically as long as it is in self-defense or in the taking of vengeance for genuine harm done. Stealing is likewise presented as morally neutral if the victim is a criminal; Lisbeth Salander steals a vast sum from a corrupt industrialist in the first book, but this is not presented as problematic in any way.

The Millennium Trilogy, then, is highly problematic for Christian readers because of the way it implicitly endorses a worldview that is directly contrary to Christian ethics. Because the books’ moral issues never come to the surface, but rather remain unstated and unaddressed, the casual reader of the books will tend to be drawn to an uncritical acceptance of the worldview of the stories.

For readers who are critically aware and can detect these issues, the series is less directly problematic but is likely to contribute to desensitization toward these topics and attitudes. Further, there is no thematic richness or insight in the books that would make the reading worth doing with caution. Readers who enjoy the genre should note that there are many excellent crime fiction novels that can be enjoyed without dealing with the normalizing of sin.

A familiarity with the books can be valuable for the working apologist, however, because of the vivid way in which they illustrate a key problem for apologists today: that with no common understanding of ordinary sin, it is difficult to present the gospel in a meaningful way.

AN INCONSISTENT WORLDVIEW

Although the worldview presented in these books treats a wide range of sinful behavior as perfectly normal, Larsson was surprisingly not a moral relativist. Influenced by the example of his grandfather’s anti-Nazi views, Larsson was committed to fighting fascism and defending freedom. As a journalist who investigated extreme right-wing groups and worked to expose neo-Nazi activity in Sweden, he was constantly in danger of assassination; it was at least in part for this reason that Larsson never married his lifelong partner, Eva Gabrielsson.2 He was genuinely dedicated to denouncing the evils of sexual trafficking and violence against women. Larsson was to be commended for confronting and addressing issues such as the ongoing crime of immigrant women being imported as sex slaves. It was good and right for Larsson to condemn those who are in the legal justice system who abuse these women or overlook the crimes as unimportant.

This stance against sexual trafficking and sexual abuse is particularly interesting given that Larsson also endorsed what the secular world calls sexual liberation. The rightness of gratifying one’s physical and emotional desires is taken for granted. Self-control and faithfulness are not presented as virtues. The ability to have sexual relationships purely for physical pleasure, with no emotional connection, is presented as clearly positive. As a result, the books undermine Larsson’s moral vision in a disturbing way.

Since marriage and biblical sexual ethics are irrelevant in this worldview, the only thing that differentiates the “good” sexual behavior of Mikael Blomkvist and Salander from the “evil” sexual behavior of the villains is the consent of the participants.

For instance, Larsson took great pains to depict Blomkvist’s ongoing adulterous affair with Erika Berger as one to which all the parties consent, which therefore rendered it entirely satisfactory: “[Berger] had a tenderhearted husband who loved her and with whom she was still in love after fifteen years of marriage. And on the side she had a pleasant and seemingly inexhaustible lover, who might not satisfy her soul but who did satisfy her body when she needed it.”3 Larsson even gave us the husband’s perspective: “Beckman [Berger’s husband] eventually convinced [Blomkvist] that if he tried to sabotage his marriage to Berger, he could expect to see Beckman come back sober with a baseball bat, but if it was simply physical desire and the soul’s inability to rein itself in, that was OK as far as he was concerned.”4

However, distinguishing between acceptable and sinful acts based on the consent of the participants is not only a very fine line, but one that is far more unstable than people may want to admit—something that Larsson in fact showed, though probably without intending to. Larsson’s worldview provides no basis for distinguishing what is good and healthy from what is sinful and destructive, other than the intentions of the participants. Given the endorsement of acting on one’s own sexual desires, unrestrained by traditional biblical morality or the bounds of marriage, it is very easy to see how a good, “sexually liberated” character could slide over into behavior that even Larsson condemns as evil.

Salander is the prime example of this gray area. She is brilliant and resourceful, but she is also the victim of rape and of years of psychological abuse. In The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, she ends up having a sexual relationship with the much older Blomkvist. She falls in love with Blomkvist, but he clearly has no intentions of forming a serious relationship with her. Salander cuts off Blomkvist when she realizes that he is having sexual relations with other women; that, in effect, he is cheating on her. Salander is shown to be hurting—but Blomkvist is still depicted completely sympathetically.

The second book opens with Salander vacationing on an island in the Caribbean, where she initiates a sexual relationship with a naive young man, with no emotional connection other than mild friendship. After she leaves the island, the young man is never mentioned again; Salander has just done to another person what Blomkvist did to her. Although Salander and Blomkvist seem to be presented in the books as liberated and healthy, in sharp contrast to the abusive relationships that are so strongly condemned in the books, the story at least hints that the reality is far more disturbing. It seems Larsson did not notice the way he undercut his own fantasy of sexual liberation.

NO SIN, NO GOSPEL

Until relatively recently, in the West apologists could take for granted that others in the culture shared their basic understanding of sin, and move forward from there. Given the reality that all people sin, the natural question is, What solution is there for that sin? The gospel might or might not have been immediately acceptable as a solution, depending on the objections that people had, but the concept of needing salvation was at least comprehensible.

The worldview so vividly presented in the Millennium Trilogy, however, presents an almost intractable problem. Because the range of behaviors regarded as acceptable has been widened so much, only extremely wicked acts are considered truly wrong. Thus, in the world of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, only particularly bad people sin; for instance, the gangsters, corrupt politicians, and abusers of women. In such a world, it is easy to give oneself a comforting label as one of the good guys—anyone who is not a murderer or rapist is a good person, more or less. In such a context, the announcement that Jesus Christ can forgive your sins is completely irrelevant. Either you don’t need to be forgiven, because you haven’t done anything really wrong, or you’re so terrible that you don’t deserve to be forgiven (like the loathsome Zalachenko).

It thus becomes easier to understand why some Christians have resorted to presenting a “self-help” style version of the gospel, in which Jesus is a moral example or a facilitator to help people have a better life right now; this may seem like the only way to share the gospel with people who do not understand their need for salvation. This approach ultimately distorts and misrepresents the gospel; it may seem like a way around the secular stonewall of indifference, but it leads to a dead end. The orthodox Christian apologist must then find a way to awaken people’s sense of sin; otherwise, a gospel of the forgiveness of sins will have no meaning, let alone any relevance.

THE IMPLICATIONS FOR APOLOGISTS

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and its sequels vividly present the conundrum of a thoroughly secularized culture grappling with questions of morality. The books themselves do not acknowledge the inconsistency and ultimate bankruptcy of the worldview that they present, but they are a valuable source of insight for apologists who must address these issues. These books are, in some ways, canaries in the coal mine: since Europe is significantly further along in the post-Christian secularization process, these Swedish novels give a glimpse of the challenges that America may face in the future.

And yet there is a glimmer of hope even in the bleak world of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. These books center on crime, and therefore also punishment; there are wicked villains, and heroes of a sort. The books assume that the reader will applaud the work of the journalists who strive to end sex trafficking, and condemn the men who abuse women.

Even in a thoroughly secularized culture, there remains some part of the human heart and mind that recognizes that there is such a thing as good and evil, and that we ought to pursue the good and reject the evil. The challenge for apologists is to find ways to take that dim spark of moral knowledge that can at least recognize the evil of sexual trafficking and rape, and fan it into a flame of desire to know the One who is the ground of all morality.

How Can We Reawaken a Sense of Sin in a Jaded Culture?

- As apologists, present sin in the context of the good that it breaks or distorts.

- Encourage an awareness and appreciation of real beauty. In a lowest-common-denominator media culture, the ugliness of sin doesn’t stand out, but set against real purity and beauty, it becomes clearer.

- Encourage the experience of silence and unscheduled, silent reflective time—promote “media fasts” among young people. People need the opportunity to think through and grapple with the significance of their choices.

Holly Ordway is the Chair of the Department of Apologetics at Houston Baptist University. She holds a Ph.D. in English from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, an M.A. in English literature from UNC Chapel Hill, and an M.A. in Christian apologetics from Biola University. She is the author of Not God’s Type: A Rational Academic Finds a Radical Faith (Moody, 2010) and speaks and writes regularly on literature and literary apologetics.

NOTES

- C. S. Lewis makes this case particularly clearly in The Abolition of Man.

- “Stieg Larsson, Biography,” The Literary Magazine of Swedish Books and Writers, http://www.stieglarsson.com/Life-and-work.

- Stieg Larsson, The Girl Who Played with Fire (New York: Vintage Books, 2009), 149.

- Ibid., 257.