This review first appeared in the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL, volume 38, number 01 (2015). For further information or to subscribe to the Christian Research Journal go to: http://www.equip.org/christian-research-journal/

Film Review

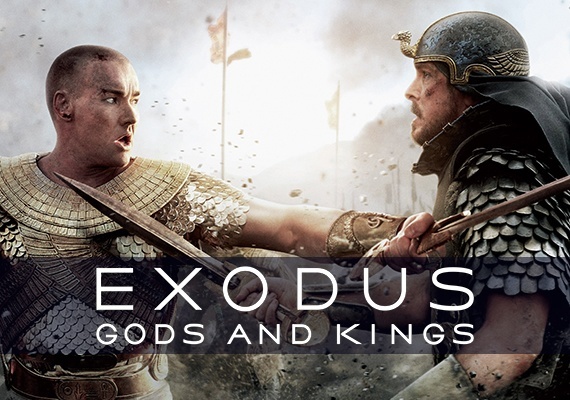

Exodus: Gods and Kings

Directed by Ridley Scott

(20th Century Fox, 2014)

The Exodus Delusion: Ridley Scott’s Atheistic Biblical Epic

“Do you believe in coincidence?” This is a key question in Exodus: Gods and Kings, the 2014 film directed by Ridley Scott of Alien and Blade Runner fame. Joshua’s father Nun (played by Ben Kingsley) believes his chance meeting with Moses (played by Christian Bale) has been ordained by God. At this point early in the film, Moses is skeptical. Sometimes it is hard to tell if something is meaningful or a coincidence. Sometimes the coincidences pile up until we have no choice but to believe they are the intentional design of an intelligent Being. At other times, an unusual occurrence may just be a coincidence that we are reading too much into. Not every natural disaster is God’s judgment, and not every dream is a message from God.

Exodus establishes the theme of ambiguous coincidences right from the start. The film begins with an Egyptian priestess examining the entrails of a sacrificed bird. “What do the entrails say?” Pharaoh asks her. “They don’t say anything,” replies the priestess. “They imply,” and thus they are open to “interpretation.”

As a film, Exodus is also open to interpretation. It can be hard to see this if we approach the film unaware of our own assumptions. As believers, we are often so familiar with biblical stories, we read into cinematic portrayals things that are not there. To evaluate a movie’s interpretation of the Bible, we should ask ourselves how a non-Christian would interpret the movie if he or she didn’t know anything about the Bible. We have to be sure to see only what is there and not what we assume is there.

In the case of Exodus, the film is ambiguous. Director Ridley Scott is a self-described atheist, so why would he make a film about religion? He has something to say about religion, but he can’t say it unambiguously, or Christians won’t go to see his movie. And he needs Christians to see the movie in order to recoup his $140 million budget. So he doesn’t say anything about religion. He implies it.

For those who have eyes to see, Exodus: Gods and Kings presents an important picture of American cultural attitudes toward religion today. Scott has updated the old-fashioned biblical epic for the twenty-first century. But he does more than simply add computer effects to a story we’ve already seen before. He uses the biblical story to reflect a new idea about religion. For Scott, as indeed for many people these days, religion is an irrational superstition, and the God of the Bible is a moral monster. This is a biblical epic Richard Dawkins could love.

A Bible Story Safe for Scientism. Pharaoh believes the will of the gods can be divined through an examination of an animal’s intestines. Yet Moses—at this point still believing he is the illegitimate son of Pharaoh’s daughter—scoffs at those who would “abandon reason and follow omens.” A few scenes later, Moses engages in apologetic debate with the elders of the Hebrew slaves. He says he wants to “convince” them that their religion is false, because “unrealistic belief leads to fanaticism,” which fosters rebellion. He tells his devout wife Zipporah that “believing in yourself” is preferable to believing in religion, and in a conversation with his son, he seems to equate religion with saying “what people want to hear.” It is hard not to take Moses’s repeatedly skeptical comments as expressing the attitude of the filmmakers.

Exodus intentionally casts doubt on many of the core claims of its own story. Most significantly, Moses hits his head on a rock just before seeing the burning bush. Even Zipporah suggests that his vision could have been due to a concussion. The fact that none of the other characters ever see or hear God in the film reinforces the hallucination interpretation. At multiple points, the film reminds us of the possibility that Moses is “schizophrenic,” as actor Christian Bale said in an interview about the film.

Likewise, it seems significant that the story of Moses being put in a basket is never shown. The events are related by Nun, but we the audience never see them. While Moses’s sister Miriam does seem to confirm the events later in the film, the way the events are narrated cinematically casts doubt on their veracity. And even when we do seem to see miracles on screen, they are always carefully staged to allow for a scientific explanation. In the case of the ten plagues, the film actually has one of Pharaoh’s advisors explicitly argue for a scientific explanation. The scene is played for laughs, but the doubt is still established.

It is no coincidence that Moses does not carry a staff in Exodus. In the Bible, God uses Moses with his staff as the means to cause the miraculous signs (Exod. 4:17), including the plagues and the parting of the Red Sea. In the film, however, these events simply happen, without Moses being involved. (The film represents the Red Sea being parted by a tsunami caused by a meteorite!) Furthermore, Moses carries a sword instead of a staff as part of the film’s portrayal of religion as violent and barbaric.

The Plagues As Religious Terrorism. On one interpretation, Exodus: Gods and Kings is the story of Moses’s gradual conversion from agnostic skeptic to devout prophet. He starts the film believing only in himself and ends up humbled before God. But the film also can be interpreted as a critique of religion, in particular the idea of religious violence and exclusivism. Exodus is not so much the story of Moses’s conversion to theism as the story of his coming to accept the Hebrews as “his people” and his willingness to engage in violence on their behalf.

The most striking cinematic choice Scott made as director was to use an eleven-year-old boy to portray God. This is not necessarily blasphemous, since the incarnate God was actually an eleven-year-old boy at one point. But when we see God basically throwing a fit about Pharaoh’s treatment of the Hebrews, we see the ideological reason for Scott’s choice. He is implying that the Old Testament God is like a petulant child who gets irrationally angry and makes extreme demands.

When Moses returns to Egypt, he initially starts what can be described only as a terrorist campaign against the Egyptians. He arms the Hebrews for war and trains them to fight. They bomb nonmilitary targets that harm civilians. Moses says his strategy is to make life intolerable for ordinary Egyptians so they will rise up in rebellion against Pharaoh and force him to give in to the Hebrews’ demands. After a few days of battle, Moses has another vision of God. “Where have you been?” Moses asks. “Watching you fail,” replies God. Moses explains that mounting a military rebellion takes time, but God is impatient.

The implication is not that God disagrees with Moses’s strategy, only that it is taking too long. So God begins the ten plagues (Exod. 7–12), which are portrayed as the same strategy just on a bigger scale. Like Moses’s terrorist attacks, the plagues also kill civilians. It is a little much even for Moses, who complains to God, “This is affecting everyone, so who are you punishing?” After nine plagues, Moses begs God to stop. He calls the plagues “cruel” and “inhumane.” “Anything more would be revenge,” he says. God defends revenge and tribalism, telling Moses, “You do not yet see them as your people.” After the death of the firstborn, Pharaoh says, “Is this your god? Killer of children? What kind of fanatics worship such a god?” This is the film’s vision of God: a baby killer only a dangerous fundamentalist could love.

Now, the issue of violence in the Old Testament raises valid questions that are important for Christian apologists to address. For those interested in a serious exploration of those questions, I recommend Paul Copan’s book Is God a Moral Monster? Making Sense of the Old Testament God (Baker, 2011). But Exodus: Gods and Kings is not interested in trying to make sense of God. The film is interested in portraying God as an angry and vengeful child who inspires His followers to commit violence in His name. The film even makes a point to remind us that the Hebrews would have to kill the Canaanites when they arrived at the Promised Land, and portrays Joshua as a psychopath who smiles while being whipped by his slave driver.

Moses, the Exception? To be fair, the film’s representation of Moses is not entirely negative. Moses is credited with the (anachronistic) idea that all people should be treated equally and given “the same rights.” The film seems to approve of Moses’s idea to write down the law, so that his people could live together in peace after he died. And Moses’s willingness to disagree with God comes off as a positive character trait. But these seem to be positive qualities of Moses himself, not of the religions that descended from him. After Moses stands up to Pharaoh to protect Miriam, she tells him, “It is not just any man” who would protect his servant. The suggestion is that the real hero here is Moses. It is Moses to whom we owe the origin of the rule of law, not God. Religion, according to Ridley Scott, is dangerous.

Each individual miracle in Exodus: Gods and Kings could have a natural, scientific explanation. But when you put them all together, it seems less and less likely that they are purely random. Surely, if a meteorite caused a tsunami at exactly the right moment to save the Hebrews, then it must have been sent by God, right? That is the way religious people think. Ridley Scott is not religious. And there are so many hints in the film that he is subverting religion that it is hard to interpret them as coincidences. —John McAteer

John McAteer is assistant professor at Ashford University where he serves as the chair of the liberal arts program. Before receiving his PhD in philosophy from the University of California at Riverside, he earned a BA in film from Biola University and an MA in philosophy of religion and ethics from Talbot School of Theology.

Subscribe to the award-winning CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL. Click here for more information.