Listen to this article (14:58 min)

Cultural Apologetics Column

This article was published exclusively online in the Christian Research Journal, Volume 46, number 03 (2023).

When you support the Journal, you join the team and help provide the resources at equip.org that minister to people worldwide. These resources include our ever-growing database of over 1,500 articles, as well as our free Postmodern Realities podcast.

Another way you can support our online articles is by leaving us a tip. A tip is just a small amount, like $3, $5, or $10, which is the cost of a latte, lunch out, or coffee drink. To leave a tip, click here

Film Review

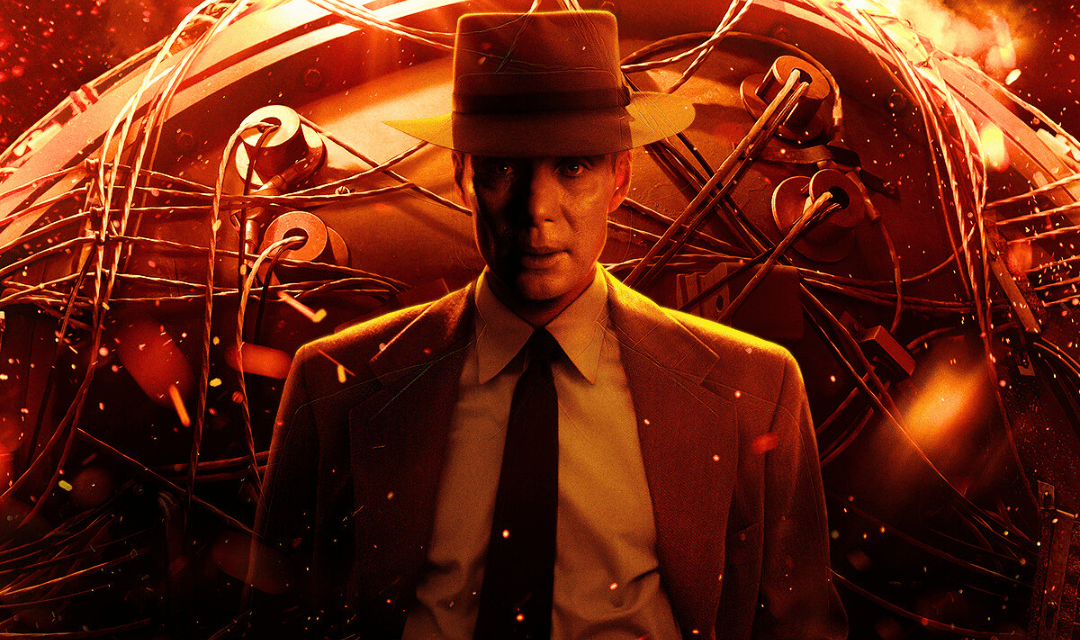

Oppenheimer

Written and directed by Christopher Nolan

Based on American Prometheus (Vintage Books, 2006) by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin

Produced by Emma Thomas, Charles Roven, and Christopher Nolan

Starring Cillian Murphy, Emily Blunt, Matt Damon, Robert Downey Jr., Florence Pugh, Josh Hartnett, Casey Affleck, Rami Malek, Kenneth Branagh

Distributed by Universal Pictures

(R, 2023)

**Editor’s Note: This article contains spoilers for Oppenheimer.**

Click here to listen to the audio of this article.

Tragic figures are often complex, multifaceted characters with inscrutable, usually conflicting motivations. The story of Prometheus is perhaps the most well-known of the classic mythological tragedies in the pop culture lexicon today, thanks to the likes of Mary Shelley’s 1818 Frankenstein (subtitled The Modern Prometheus), Chris Carter’s 1997 Emmy-nominated masterpiece from The X-Files (“The Post-Modern Prometheus”), and Ridley Scott’s 2012 Alien prequel, Prometheus. By simply invoking the name of the character, a creative communicates themes of forbidden knowledge, perpetual suffering, and the grotesque.1

Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer (2023) is a film that more or less frames the life and times of Julius Robert Oppenheimer, the “father of the atomic bomb,” as a humanistic retelling of the Prometheus myth set primarily in twentieth century America. It is one of the most “talky” films in recent memory, with practically every scene featuring well-acted characters speaking in hushed or urgent tones, and an occasional outburst of emotion thrown in for good measure. A staggering three-hour runtime and a nigh-obsessive focus on the primary character ensures the film oozes the kind of appeal of old Hollywood epics like Ben-Hur (1959) and Doctor Zhivago (1965).

Ever since The Dark Knight (2008), Nolan’s films have become cultural touchstones, and Oppenheimer is no different. Despite being set throughout the early-to-mid twentieth century and tackling timeless themes, none of his previous films have felt more “of the moment.” Philosophically, the film explores the tug-of-war between fascism and communism that characterized American politics during the Second World War and immediately thereafter. But in Nolan’s hands, these ideas seem no less relevant to the current political landscape, contributing to the film’s clearly defined sense of purpose as a kind of modern (albeit lengthy) parable that contemplates the psychological and emotional toll of genius.

The Destroyer of Worlds. The connection between myth, religion, and Oppenheimer is not subtle in Nolan’s film. Pop culture has kept the memory of Oppenheimer alive through the infamous quote, “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” The line is lifted from the Bhagavad Gita, a Hindu religious text. Sanskrit scholar Stephen Thompson does a good job of explaining the quote contextually in both the Gita and as Oppenheimer used it, as well as heightening the connection to the theme of forbidden knowledge that runs throughout the film, when he recognizes that “the physicists have known sin; and this is a knowledge which they cannot lose.”2 As a result, Nolan’s version of Oppenheimer comes across as a mythological and apocalyptic (perhaps even semi-religious) figure.

Like many other “auteur” directors, there is a clear through-line that threads Nolan’s work together. If one were shown five minutes of an unreleased film and not told that Nolan directed it, one could still identify it based on the cinematography, the dialogue, and the seemingly constant thrum of nerve-grating music running beneath each scene. Much of Oppenheimer, unsurprisingly, was inspired by the work Nolan put into the time travelling thriller, Tenet (2020), especially alongside Robert Pattinson, who gifted him a book of Oppenheimer’s speeches towards the end of the shoot.3

These seeds of initial fascination developed into something close to an obsession for Nolan, as reflected in the way the film has an almost morbid fixation on Oppenheimer himself. Cillian Murphy, who plays the character, is in practically every shot of the movie. His sunken features and haunted stare tinge every scene with a kind of melancholy, and one gets the sense that Murphy’s Oppenheimer is a kind of dark prophet, someone who has been cursed with the ability to see into the quantum realm and witness the destruction of the world. That might come across as somewhat lofty and pretentious; but make no mistake, that is exactly what Nolan intended.

In an interview with the New York Times, Nolan had the following to say when asked about production notes for the film characterizing Oppenheimer as “the most important person who ever lived”:

In Hollywood, we’re not afraid of a little hype. Do I genuinely believe it? Absolutely. Because if my worst fears are true, he’ll be the man who destroyed the world. Who’s more important than that?….I think it’s very easy to make the case for Oppenheimer as the most important person who ever lived….His story is central to the way in which we live now and the way we are going to live forever. It absolutely changed the world in a way that no one else has changed the world. You talk about the advent of the printing press or something. He gave the world the power to destroy itself. No one has done that before.4

Nolan’s perspective on the man himself is an interesting one — it really makes one wonder what Nolan would do with a film about the life of Jesus of Nazareth. Perhaps it is the fundamentalist in me, but I think I would agree with Nolan that the man who destroys the world would be the most important man who ever lived. Nolan wrote Oppenheimer, and John wrote Revelation. I have watched one and read the other, and I cannot help but wonder if Oppenheimer is Christopher Nolan’s apocalypse.

An American Tragedy. The film is based on the Pulitzer Prize-winning book by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer,5 the subtitle of which serves as an apt descriptor for how Nolan frames the narrative surrounding the physicist. The filmmaker cannot singularly be credited with casting Oppenheimer in a mythic light, or even as a romantic figure in the classical sense. Indeed, many biographers have come along through the years seeking to depict Oppenheimer more sympathetically as a tragic figure whose past comes back to haunt him.

Early in his life, upon discovering politics, Oppenheimer developed associations with the American Communist Party. Yet his politics were frequently as theoretical as his scientific endeavors, which is why, despite years of surveillance and tapping phones, government agents never managed to prove that Oppenheimer was, in fact, a dedicated communist.6 These early connections to communist party activists, however loose, would become the focal point of a government investigation in Oppenheimer’s later years that ultimately led to him being discredited in the political sphere.

Nolan, as others before him, no doubt taking a cue from American Prometheus, uses these details as an opportunity to position Oppenheimer as a victim of the Red Scare. Despite the fact that politics is, in the real world, a sea of murky waters, Nolan’s film has clear heroes and villains: Edward Teller (Benny Safdie), for example, is portrayed as the turncoat scientist who throws Oppenheimer under the bus during security hearings spun up by the cerebral machinations of Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.) in a virtual witch hunt that resulted in Oppenheimer’s security clearance being revoked and his “virtual expulsion from the physics community.”7

Characterizing Oppenheimer as a victim of twentieth century politics makes for a tragic arc, but it nevertheless becomes quite difficult to argue that Nolan’s portrayal of him is entirely compassionate. The man is also shown to be a self-absorbed womanizer, whose huge intellect belies his terrible insecurities. This facet of the man’s life is, perhaps, less well known than others, but has nonetheless been documented over the years.8

What begins to emerge over the course of the film’s three-hour runtime is a complex, conflicted figure who becomes, in a very real sense, his own worst enemy. And this, of course, is what makes tragic figures work literarily — the idea of a fatal flaw or hamartia, which originates from the Greek word meaning to err or to miss the mark. Importantly, the same Greek word, hamartia, is used in the original autographs of Scripture to denote sin. But in the tragic sense of the word (the dimensions of which should not be entirely excluded from hermeneutical discussions), the fatal flaw or hamartia is the consistent thing or defect that runs throughout a character’s life or development that contributes to their downfall. This is usually something that arises from within the character, that plagues them throughout the narrative — less Achilles’ heel and more Achilles’ hubris.9

Consider, by way of example, the anger and ambition of Anakin Skywalker, which Palpatine manipulates across the three Star Wars prequels.10 Or, more traditionally, Oedipus’s overconfidence in his own reasoning in Oedipus Rex. These are all examples of fatal flaws in classically tragic narratives. Oppenheimer channels this literary concept by giving its titular character a kind of fatal flaw in the form of his intellectual pride. Oppenheimer, as portrayed in the film, is too smart for his own good, with the picture subtly suggesting that his intellectual capacity is as much a curse as it is a blessing, dooming him constantly to question the mathematical probability of whether his creation of nuclear weapons is going to lead to the destruction of the world. And not only this, but the pride Oppenheimer takes in being the smartest man in the room and making advances toward women, and his intellectual curiosity, which pushes him to flirt with communist ideals and bring in unconventional personnel to work on the bomb project, all contribute to his eventual undoing.

At World’s End. There is no debating that Oppenheimer casts a giant shadow over the modern era — and Nolan’s point about the man’s importance to history is well taken. Biographical films like this one often make splashes, and this is a film that is sure to clean house during awards season. For years to come, reviewers and film critics will spill untold amounts of ink writing about the film’s warnings regarding unchecked nationalism or its old school liberal political philosophy (which is not necessarily a bad thing, as it looks nothing like the kind of nonsense frequently propagated today). This review has intentionally avoided picking those particularly low-hanging fruits.

Instead of taking the bait and quibbling over details that the film itself leaves vague (at one point in the back half of the picture, Teller flat out tells Oppenheimer that no one knows what Oppenheimer actually believes about anything, or what his convictions are, politically or otherwise), the Christian apologist would fare far better in discussions by following the mythic threads that Nolan is clearly so fascinated by. The film begins with a summation of the Prometheus story and concludes with a vision of a nuclear holocaust that does not look too dissimilar from Peter’s depiction of the day of the Lord in 2 Peter 3:10.

The point here is not to suggest that the Bible presages nuclear weapons at world’s end; rather, to emphasize the fact that Oppenheimer presents the very real possibility, however humanistic, of an apocalypse. The film mythologizes the story of the advent of nuclear bombs as the “beginning of the end,” and the man at the center of the story as a tragic figure and kind of prophet whose thirst for knowledge has very likely — in Nolan’s estimation, at least — put the world on an irreversible course toward its own destruction.

Christians today frequently relegate discussions of eschatology to exclusively theological circles. It has become something of a cliché to suggest that the only people of faith who care about how the Bible’s story ends are raving fundamentalists who are haunted by fever dreams of black helicopters after reading about locusts. And the less said about the pretentious, condescending Christian who suggests that eschatology is something of a theological footnote because their shaky hermeneutics cannot help them square what a plain reading of Scripture makes very clear, the better.

Oppenheimer demonstrates quite clearly that perhaps the “biggest” filmmaker of the modern era is absolutely fascinated by the apocalypse. And the box office reflects an appetite among people to see these kinds of stories told. For as much as the film reflects an obsession with J. Robert Oppenheimer, it also reflects an apocalyptic vision of a future in which nuclear war incinerates the Earth.

Perhaps it is time evangelicals let some of those fundamentalists rant and rave for just a little while, or at least take a page from their proverbial book. There’s an old adage among Christians who tend to avoid eschatological topics that says, “You cannot scare one into heaven.” Well, if Christopher Nolan is right about J. Robert Oppenheimer, then it’s probably time to stop using that particular maxim. After all, the difference between John’s ancient text and Nolan’s modern movie is that only one of them ends with a rescue. —Cole Burgett

Cole Burgett is a graduate of Dallas Theological Seminary and the Moody Bible Institute. He teaches classes in systematic theology and Bible exposition and writes extensively about theology and popular culture.

NOTES

- Editors’ note: Britannica explains, “Prometheus was depicted in Prometheus Bound by Aeschylus, who made him not only the bringer of fire and civilization to mortals but also their preserver, giving them all the arts and sciences as well as the means of survival.” “Promethius: Greek god,” Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Prometheus-Greek-god.

- Stephen Thompson, quoted in James Temperton, “‘Now I Am Become Death, the Destroyer of Worlds.’ The Story of Oppenheimer’s Infamous Quote,” Wired, July 21, 2023, https://www.wired.com/story/manhattan-project-robert-oppenheimer/.

- Christopher Nolan, quoted in Armando Tinoco, “Christopher Nolan on Why Robert Pattinson Is Not Part of ‘Oppenheimer’ Cast Despite Influencing Film,” Deadline, July 9, 2023, https://deadline.com/2023/07/christopher-nolan-why-robert-pattinson-not-oppenheimer-cast-despite-influencing-film-1235432771/.

- Christopher Nolan, quoted in Dennis Overbye, “Christopher Nolan and the Contradictions of J. Robert Oppenheimer,” New York Times, July 20, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/20/movies/christopher-nolan-oppenheimer.html.

- Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer (New York: Vintage Books, 2006).

- Thomas Powers, “An American Tragedy,” New York Review, September 22, 2005, https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2005/09/22/an-american-tragedy/; Michel Rouzé, “J. Robert Oppenheimer: American Physicist,” Britannica, August 1, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/biography/J-Robert-Oppenheimer.

- “Part V: The Red Scare,” in “Race for the Hydrogen Bomb,” The Atomic Archive (n.d.), https://www.atomicarchive.com/history/hydrogen-bomb/page-15.html.

- Tom Fordy, “The Sad Truth about Oppenheimer and His Women,” Telegraph, July 23, 2023, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/films/0/truth-oppenheimer-cillian-murphy-christopher-nolan/.

- For a detailed discussion of hamartia in classic tragedy, see A. C. Bradley, Shakespearean Tragedy: Lectures on Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, Macbeth (London: Macmillan and Co., 1904), https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uva.x000240890&seq=7.

- Episode I: The Phantom Menace (1999), Episode II: Attack of the Clones (2002), and Episode III: Revenge of the Sith (2005).