Listen to this article (19:33 min)

Cultural Apologetics Column

This article was published exclusively online in the Christian Research Journal, Volume 47, number 02 (2024).

This is an online article from the Christian Research Journal.

When you support the Journal, you join the team and help provide the resources at equip.org that minister to people worldwide. These resources include our ever-growing database of more than 2,000 articles, as well as our free Postmodern Realities podcast.

Another way you can support our online articles is by leaving us a tip. A tip is just a small amount, like $3, $5, or $10, which is the cost of a latte, lunch out, or coffee drink. To leave a tip, click here

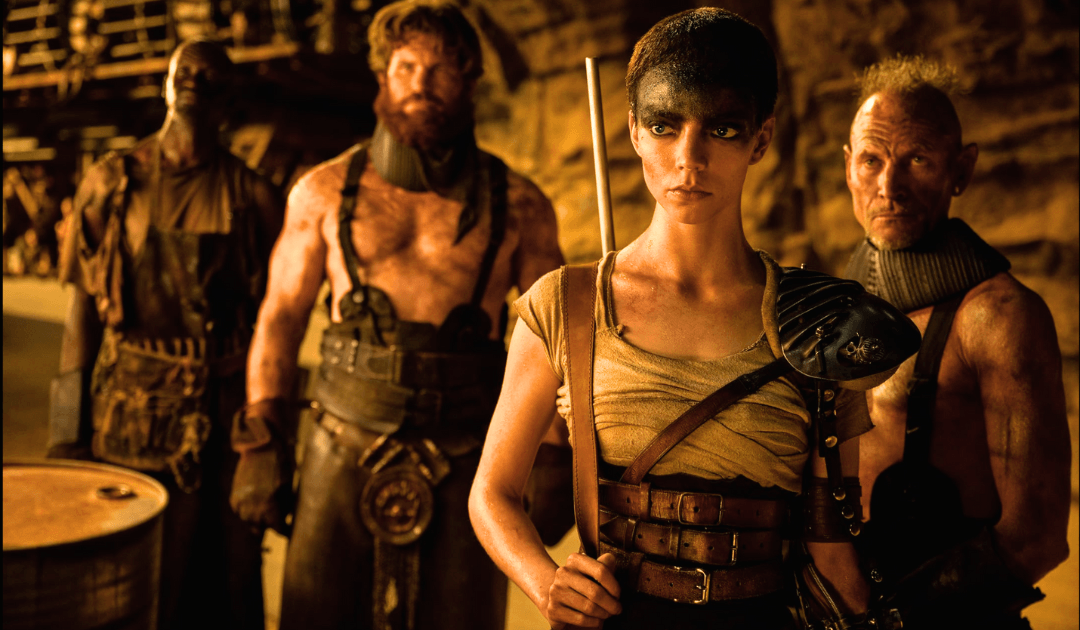

Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga

Directed by George Miller

Written by George Miller and Nico Lathouris

Produced by Doug Mitchell and George Miller

Starring Anya Taylor-Joy, Chris Hemsworth, Tom Burke, and Alyla Browne

Feature Film (R)

(Warner Bros. Pictures, 2024)

[Editor’s Note: This review contains spoilers for Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga.]

To listen to the audio of this article, please click here.

When I was a kid, my father had an old gun cabinet where he would store rifles. When he upgraded to something more secure, the guns were emptied out and the cabinet moved upstairs to my bedroom, where it became a hub for all sorts of oddities. I have a distinct memory of an old VHS tape that I found in the bowels of that cabinet when I was probably ten years old. The cover of the sleeve featured a picture of Mel Gibson in black leather, holding a sawed-off shotgun. And above that picture, in huge, bold letters, the film’s title: Mad Max.

Watching that movie was a bit like a fever dream. Set in one of those bizarre late-twentieth century apocalyptic futures (it released in 1979), the film is about a world on the brink of collapse, where law and order has disintegrated. Max Rockatansky (Mel Gibson) is one of the last honest police officers, a bastion of justice in a chaos-addled Australia. And the whole thing plays like a weird, psychedelic hallucination composed of low-budget filmmaking, relentless action, and a protagonist who is more a silhouette of a concept than an actual person, as he becomes vengeance incarnate, the idea of retribution given perfect shape and form. More than anything, though, that original incarnation of Max is cool. And the scene where he drags himself to his feet, despite a blown-off kneecap and a broken arm, to stalk down that desolate stretch of highway after a stunned Toecutter (Hugh Keays-Byrne) remains one of the most rousing sequences in any movie I’ve ever seen.

Upon initial release, however, the film was met with divided critical opinion. Tom Buckley, writing for the New York Times, called the film “ugly and incoherent,” and suggested that its target audience was “the most uncritical of moviegoers.”1 Despite this, the film was a resounding success at the box office, grossing over $100 million against a production budget of less than $500,000 — with some of the crew even paid in cases of beer — effectively making it one of the most profitable films ever when considering the box-office-to-budget ratio.2

The film’s success guaranteed a sequel, and Mad Max 2 released in 1981. It received the (better) title of The Road Warrior for release in the United States, and this is arguably the film most responsible for codifying the series’ familiar iconography. Desolate landscapes, memorably freakish characters, a narrator framing the story as something like an apocalyptic fairy tale, the crazy man with a good heart in black leather driving a souped up muscle car, all of those ingredients (most of which were present in Mad Max, just hamstrung by a low budget) were solidified in the public conscience by The Road Warrior.

The sequel has been consistently ranked among the greatest action films ever made, with legendary film critic Roger Ebert calling it “one of the most relentlessly aggressive movies ever made,” and “a movie like no other.”3 Vincent Canby reviewed the film for the New York Times, and wrote that it is “an extravagant film fantasy that looks like a sadomasochistic comic book come to life.”4 As a cinematic work of pure imagination, the film is staggeringly original. And where George Lucas looked to myth and the past for inspiration when writing Star Wars (1977), George Miller crafted a mythic vision of the future that asked, “What might happen if the world ended circa 1980?” when creating The Road Warrior.

A third film (and what would be the last in the series for thirty years) was released in 1985. Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome is Mel Gibson’s swan song as Max, and pits him against Tina Turner as Aunty Entity, a villain as glitzy as she is ruthless, who is determined to rebuild society. The film, like its predecessors, was hailed for its unrivaled action sequences, with Ebert holding it in even higher regard than The Road Warrior and calling the battle between Max and Master Blaster (Angelo Rossitto/Paul Larsson) “one of the great creative action scenes in the movies.” He concluded that Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome “is a movie that strains at the leash of the possible, a movie of great visionary wonders.”5

A fourth film in the series was in development hell for nearly thirty years. At different points, Miller expanded his vision for what he wanted the film to be, which began with the idea of making a “continuous chase.”6 But years of planning combined with Gibson’s well-documented legal troubles and aging led him to rethink casting decisions. In 2010, two years before appearing as Bane in The Dark Knight Rises (2012), British actor Tom Hardy was announced to be taking over the role of Max.7 Hardy would join the production alongside Charlize Theron, who was cast as a new character, Imperator Furiosa. The difficulties surrounding the eventual, grueling 2012 shoot were highly publicized, with much ink spilled over the on-set conflicts between Hardy and Theron.8

Despite production troubles, Mad Max: Fury Road finally released in 2015 to critical rapture. A so-so box office return made back the film’s budget, but probably ended up losing the production about $20–40 million when considering marketing costs, awards campaigns, and so forth.9 Nevertheless, the film won six Academy Awards and ended up on numerous critics’ best-of-the-year lists, with Empire naming it the best film of the 21st century in 2020.10 Reviewing the film for that same publication upon release, Ian Nathan wrote, “Max’s re-enfranchisement is a triumph of barking-mad imagination, jaw-dropping action, crackpot humour, and acting in the face of a hurricane.”11

A fairly high-profile lawsuit against Warner Bros. and a global pandemic delayed work on any follow-up feature. But, in 2020, Miller quietly toiled away on his projects during the COVID-19 lockdown, casting Anya Taylor-Joy as a younger version of Furiosa. Filming commenced in 2022 on a prequel centered upon the character, and Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga (2024) just released as the latest installment in this madcap series.

The Darkest of Angels. The new film turns back the clock about fifteen years or so before the events of Mad Max: Fury Road. But any attempt to further slot these two most recent films into a neat continuity should be taken with a large grain of salt. The first three films work as a trilogy, but with the release of Mad Max: Fury Road, the series essentially underwent a kind of “soft reboot.” For example, the film opens with Max alongside his iconic “black-on-black” Interceptor, which had been destroyed in The Road Warrior and was absent from Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome but was again destroyed in the 2015 movie. Miller himself has stated that the films were never conceived with chronology in mind and do not adhere to any kind of strict continuity. He has likened each film to fragmentary, folkloric “episodes” that revolve around a central archetypal figure: “the wanderer in the wasteland, basically searching for meaning.”12

That being said, Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga takes the version of Max’s world presented in Mad Max: Fury Road and expands it. Characters like Immortan Joe (played here by Lachy Hulme) and The People Eater (John Howard) return, while new ones such as the villainous Dementus (Chris Hemsworth) flesh out the politics of the Wasteland. Max (Jacob Tomuri) is only glimpsed in the film, while Furiosa takes center stage, with the story fleshing out her background.

Originally from the Green Place, one of the Wasteland’s last bastions of agriculture and fresh water, Furiosa is descended from the Vuvalini, a matriarchal tribe of warrior-like survivors. Early in the film, she is captured by raiders from the Biker Horde who have stumbled upon the Green Place, and taken to their leader, a warlord-cum-messiah figure named Dementus. The raiders are pursued by her mother, Mary Jabassa (Charlee Fraser) and killed, but a rescue attempt gone awry leads to Dementus forcing Furiosa to watch as he executes her mother before taking the girl as his personal captive.

Furiosa refuses to take Dementus to the Green Place, and some time later the Biker Horde stumbles across the Citadel, a cluster of three rock towers situated above an aquifer of fresh water. Dementus attempts to lay claim to the Citadel, only to inadvertently start a war he cannot hope to win with the Citadel’s despotic ruler, Immortan Joe — the ultimate villain of Mad Max: Fury Road. After striking a deal with Joe in exchange for Furiosa, Dementus is granted authority over Gastown, a nearby oil refinery crucial for the Citadel’s operations. Thus begins the journey of Furiosa, from child captive to exceptional mechanic among the ranks of Joe’s “War Boys,” to unparalleled road warrior under the tutelage of Praetorian Jack (Tom Burke), her eventual lover and the driver of Joe’s “War Rig” — the iconic truck that appeared in Mad Max: Fury Road.

Broadly speaking, themes of environmentalism have permeated the series since the beginning, and Mad Max: Fury Road received no small amount of attention for its willingness to let well-defined female characters have their own agency in its many action scenes. Both of those elements return in Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga. But this film is about more than either environmentalism or feminism; it is a thorough exploration of the loss of innocence and the banality of vengeance.

Ever since The Road Warrior framed Max’s story as something like a dark fairy tale, the stories in these films have played out more like folktales told through an unhinged, drug-induced stupor. That is to say, Miller paints them with threadbare plots and intentionally bizarre iconography to heighten the archetypal characteristics and themes at play in the narrative. By way of example, the latest film opens with Furiosa in a literal green place, reaching for a fruit that not-so-subtly channels the Eden account of Genesis 1–3. While this particular story is less interested in forbidden knowledge, it is very interested in what is lost when chaos enters in.

Furiosa is dragged out of a kind of Eden and thrown into the Wasteland, where she must learn to survive amidst the bids for power made by freakish, deformed tyrants like Dementus and Immortan Joe. In more than a few ways, the perverse and sadomasochistic imagery the series is known for is indicative of a world gone mad, not the normative way things are supposed to be. It is Miller’s vision of the monstrous that is meant to contrast against the simple, good things in life. To illustrate the point another way, throughout the series, goodness is frequently shown to be uncomplicated and ordinary — the families that both Max and Furiosa had before the chaos of the world tore them away.

The loss of childhood innocence is a central theme in Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga, highlighting the irreversible changes that the characters endure in the brutal world of the Wasteland. This theme is quite poignantly illustrated when Furiosa finally takes her revenge on Dementus. After stalking him through the Wasteland as “the darkest of angels,”13she corners him and demands the return of her childhood, symbolizing a longing that is perhaps contained within every human being — or, rather, should be contained therein — for a past purity and simplicity that, once lost, can never be reclaimed. Furiosa realizes that no matter how many times she beats on Dementus, the punches do nothing to numb her pain; and that vengeance cannot, actually, put the broken pieces of her past back together. The tragedy of this realization reflects the broader, existential despair that Miller seems fascinated by and with which he has tinged the film series since its inception. Time and again, the protagonists of these movies are confronted with the harsh reality that the world they once knew is gone, and the remnants of their former lives are but distant memories.

However, this theme finds a genuinely powerful counterpoint in Mad Max: Fury Road. In that film, when Furiosa finally returns to the Green Place of her childhood, she discovers it has been consumed by the desolation of the Wasteland. Her realization that everything she has lived and hoped for is gone is a sequence shot beautifully by cinematographer John Seale, and the film’s emotional zenith. Yet it is in this moment of despair that Max offers a lifeline of hope by proposing that, instead of running, they work together to retake the Citadel and “come across some kind of redemption.”14 It is an already powerful scene made more significant by the events of Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga, underscoring that both of these films work best as two sides of the same coin.

The Modern Apocalyptic Myth. At its core, Miller’s pentalogy of Mad Max films is the stuff of classic mythology. Each story reflects, as Miller himself notes, the very human struggle to find meaning, redemption, and the possibility of a better tomorrow amidst the chaos and destruction of a fallen world, making them a goldmine for the Christian cultural apologist.

In mythic storytelling, archetypes are the foundational elements that carry across time and cultures. This is how the American Western and the Japanese Chanbara (samurai film) can be so similar despite their obvious differences. The Mad Max series is replete with such archetypes: the hero’s journey (for both Max and Furiosa), the wanderer, the tyrant, the quest for a lost paradise. Max, as both the hero and the wanderer, is a character in perpetual motion, driven by a haunted past and an uncertain future, in search of meaning and justice. Furiosa is her own kind of “warrior woman” archetype, a figure so frequently seen in myth as a symbol of resilience and transformation.

Both are set against the Wasteland, a barren and lawless expanse, a modern-day equivalent of the chaotic realms found in ancient myths, places where heroes are tested and the forces of good and evil clash. A similar concept is seen even in the narrative of Scripture, wherein the writers draw upon the Ancient Near Eastern imagery of the desolate and waterless places as being the realms of demonic entities — an ancient Hebraism that Jesus Himself seemingly alludes to in Matthew 12:43. Demonic encounters frequently occur in desolate regions in Scripture (Luke 8:29; 11:24–26), and, of course, Jesus encounters Satan in the wilderness in Matthew 4:1–11. It is noteworthy, by the way, that Jesus rebuffs Satan in that passage using three citations from Deuteronomy — the “Second Law” given to Israel in their desert encampment on the outskirts of Canaan. The point is that the barren places are where the heroes are tested, where the forces of good and evil clash, and it is in such a setting that George Miller explores the fragility of civilization and the fundamental need for hope to carry one forward — and hope is yet another major theme introduced in the prequel that is paid off in Mad Max: Fury Road.

The structure of the Mad Max films also closely aligns with the redemptive-historical arc of Scripture. The Bible charts the journey from Eden through the trials and tribulations of a fallen world, to the hope of redemption and an ultimate restoration. Following a similar pattern, the Mad Max films portray a world where chaos enters in and disrupts the basic, fundamental, ordinary good. While most of the world is given to despair, there are a precious few to whom it is given to hope in something better.

Perhaps the cultural apologist can find no better conversation starter to point one to Jesus than the riddle posed by “The First History Man” at the conclusion of Mad Max: Fury Road: “Where must we go…we who wander this Wasteland in search of our better selves?”15

It’s an important question. And the Bible has an answer. —Cole Burgett

Cole Burgett is a graduate of Dallas Theological Seminary and the Moody Bible Institute. He teaches classes in systematic theology and Bible exposition and writes extensively about theology and popular culture.

NOTES

- Tom Buckley, “Mad Max (1979),” New York Times, June 14, 1980, https://web.archive.org/web/20110521024820/http://movies.nytimes.com/movie/review?res=EE05E7DF173BBB2CA7494CC6B6799C836896.

- Joanna Robinson, “8 Reasons Why Mad Max is the Most Improbable Franchise of All Time,” Vanity Fair, May 15, 2015, https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2015/05/mad-max-history.

- Roger Ebert, “Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior,” Chicago Sun-Times, January 1, 1981, https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/mad-max-2–the-road-warrior-1981.

- Vincent Canby, “Post-Nuclear ‘Road Warrior,’” New York Times, April 28, 1982, https://www.nytimes.com/1982/04/28/movies/post-nuclear-road-warrior.html.

- See Roger Ebert, “Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome,” Chicago Sun-Times, July 10, 1985, https://web.archive.org/web/20130326174707/http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=%2F19850710%2FREVIEWS%2F507100301%2F1023.

- See Adrian Martin’s remarks regarding Miller’s ideas for the series in Adrian Martin, The Mad Max Movies (Australian Screen Classics) (Redfern, New South Wales: Currency Press, 2003), 7ff.

- Adam Rosenberg, “EXCLUSIVE: ‘Mad Max’ Speaks! ‘Bronson’ Star Tom Hardy on His Coming Game-Changer,” MTV, December 1, 2009, https://www.mtv.com/news/5w497n/exclusive-mad-max-speaks-bronson-star-tom-hardy-on-his-coming-game-changer.

- Julie Miller, “Tom Hardy Publicly Apologizes to Mad Max Director George Miller,” Vanity Fair, May 14, 2015, https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2015/05/tom-hardy-mad-max-apology.

- Pamela McClintock, “And the Oscar for Profitability Goes to … ‘The Martian’,” The Hollywood Reporter (Mar. 3, 2016), https://web.archive.org/web/20161012024433/http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/oscar-profitability-goes-martian-872507.

- Bryon Bishop, “Mad Max: Fury Road Wins Most Awards of the Night with Six Oscars,” Verge, February 29, 2016, https://www.theverge.com/2016/2/29/11131218/mad-max-fury-road-most-awards-academy-awards-2016; “The 100 Greatest Movies of the 21st Century: The Critics’ List,” Empire, January 24, 2020, https://www.empireonline.com/movies/features/the-100-greatest-movies-of-the-21st-century-the-critics-list/.

- Ian Nathan, “Mad Max: Fury Road Review,” Empire, November 5, 2015, https://www.empireonline.com/movies/reviews/mad-max-fury-road-review/.

- George Miller, quoted in Brendon Connelly, “George Miller Interview: Mad Max and the Making of Fury Road,” Den of Geek, October 13, 2015, https://www.denofgeek.com/movies/george-miller-interview-mad-max-and-the-making-of-fury-road/.

- Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga [Film], directed by George Miller, written by George Miller and Nico Lathouris (Burbank, CA: Warner Bros. Pictures, 2024).

- Mad Max: Fury Road [Film], directed by George Miller, written by George Miller, Brendan McCarthy, and Nico Lathouris (Burbank, CA: Warner Bros. Pictures, 2015).

- Mad Max: Fury Road [Film], directed by George Miller.