Cultural Apologetics Column

This article was published exclusively online in the Christian Research Journal, Volume 46, number 04 (2023).

When you support the Journal, you join the team and help provide the resources at equip.org that minister to people worldwide. These resources include our ever-growing database of over 1,500 articles, as well as our free Postmodern Realities podcast.

Another way you can support our online articles is by leaving us a tip. A tip is just a small amount, like $3, $5, or $10, which is the cost of a latte, lunch out, or coffee drink. To leave a tip, click here

**Editor’s Note: This review contains spoilers for Godzilla Minus One.**

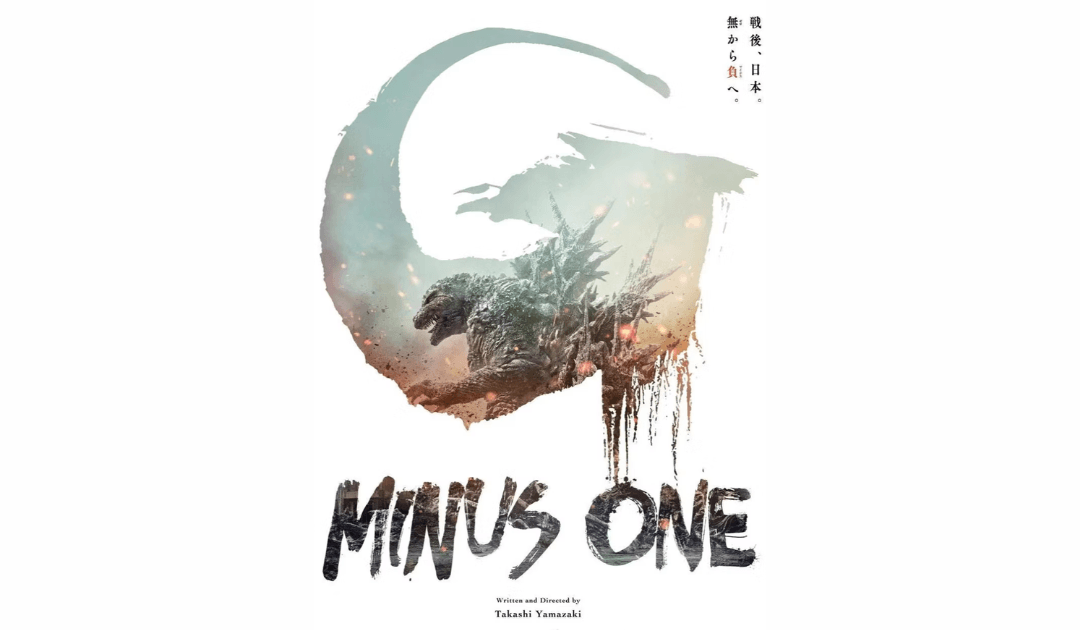

Godzilla Minus One

Written and Directed by Takashi Yamazaki

Produced by Minami Ichikawa, Kazuaki Kishida, Keiichirō Moriya, and Kenji Yamada

Starring Ryunosuke Kamiki, Minami Hamabe, Yuki Yamada, Munetaka Aoki, Hidetaka Yoshioka, Sakura Ando, and Kuranosuke Sasaki

Distributed by Toho

(PG–13, 2023)

Since stomping onto screens in 1954, the Godzilla franchise has evolved from a singular cinematic phenomenon into a complex and multifaceted cultural icon. Initially conceptualized by prolific filmmaker Tomoyuki Tanaka as a means of exploring Japan’s post-World War II anxiety, and brought to life by director Ishirō Honda, Godzilla (“Gojira” in Japanese, a portmanteau of “gorira,” meaning “gorilla,” and “kujira,” meaning “whale”) emerged as a formidable metaphor for the devastating effects of nuclear war — a theme deeply ingrained in the Japanese psyche following the detonation of atomic bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945.1

Gojira

The original film, Gojira, was released in Japan in 1954 and maintains a prestigious position in film history as both the genesis of the series and a somber look at the condition of the Japanese zeitgeist following the Second World War. Directed by Honda, a veteran who had witnessed the horrors of war firsthand, Gojira encapsulates the collective trauma experienced by a nation in the wake of nuclear destruction.2 Portrayed as an ancient creature awakened and mutated by nuclear testing, Godzilla becomes a symbol of the atomic bomb itself — an unstoppable force of destruction, born from human technological arrogance. The movie’s dark tone, stark black-and-white cinematography, and haunting score by Akira Ifukube together conjure an atmosphere of dread and despair, mirroring Japan’s national mood in the 1950s.

The film also served to critique the rapid modernization and rearmament of Japan, raising ethical questions about the responsibility of honest science and the consequences of military escalation. The film’s narrative, while centered on the terror of the monster’s rampage and the desolation left in its wake, nonetheless delves into the moral dilemmas faced by its characters, particularly the tormented scientist, Dr. Serizawa (Akihiko Hirata). His creation of the “Oxygen Destroyer,” a weapon devised to kill Godzilla and potentially as devastating as the atomic bomb, underscores the film’s message about the dangers of unchecked scientific advancement.

Gojira resonated with global audiences as well, tapping into universal fears of nuclear annihilation during the Cold War era, the result of a Japanese-American re-edit that attempted to seamlessly insert scenes with Raymond Burr into the film and was released in 1956 under the title Godzilla, King of the Monsters!3 International success paved the way for the franchise’s expansion, however the original film’s moody atmosphere, serious tone, and reflection of a nation’s trauma at a particular moment in history set it apart from many of the later sequels and adaptations.

The trajectory of the franchise’s development mirrors the shifting societal, political, and technological landscapes in the decades since its inception. The early Showa era films (1954–1975)4 slowly morphed Godzilla from a terrifying symbol of nuclear destruction into a more benign character, reflecting the changing attitudes towards technology and modernization in post-war Japan, and because the films did well financially. Films from this era, such as Godzilla Raids Again (1955) and King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962), showcase the transition from dark allegory to entertainment-focused narratives that capitalized on Godzilla’s cross-cultural appeal.

Moving into the Heisei period (1984–1995), the franchise underwent a kind of renaissance, returning to its darker roots with enhanced special effects and a renewed emphasis on the original film’s allegorical underpinnings. In 1998, the franchise received its first American adaptation, with a massive budget behind it and cutting-edge special effects to boot. While it proved to be an interesting experiment, Roland Emmerich’s Godzilla film is an abysmal affair, becoming a box office flop and a black mark on the series’ storied history.

The Millennium series (1999–2004) and the current Reiwa era (2016–present) marked a diversification and globalization of the franchise, expanding its appeal and raising pertinent environmental and ethical questions in a modern context. A second big-budget Hollywood adaptation from Legendary Pictures in 2014, simply titled Godzilla, sparked off the now hugely popular “Legendary Monsterverse,” which includes Kong: Skull Island (2017), Godzilla: King of the Monsters (2019), Godzilla vs. Kong (2021), the upcoming Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire (2024), and two television series that premiered in 2023, Skull Island (Netflix) and Monarch: Legacy of Monsters (Apple TV+).

What’s Old is New Again. 2023 also saw the release of parent company Toho’s first Godzilla feature film since 2016. While many of the sequels and adaptations have been said to emulate the original, with respect to positioning Godzilla as a kind of metaphor for something (nuclear war, environmental crises, even mythological ideas), none have done so with regard to the original’s subject matter like this year’s Godzilla Minus One.

Beginning in 1945, the film opens with kamikaze pilot Kōichi Shikishima (Ryunosuke Kamiki) landing on Odo Island, claiming to have technical issues with his plane. This is a ruse, of course, that Navy Air Service technician Sōsaku Tachibana (Munetaka Aoki) sees through immediately, though he does not fault Shikishima for wanting to live. He does, however, begrudge Shikishima for panicking when Godzilla, a local Odo Island legend, attacks the outpost and only Shikishima and Tachibana survive.

The following year, Shikishima returns home, only to find that his family was wiped out during Operation Meetinghouse, when United States forces dropped bombs on Tokyo. Shikishima also takes in Noriko Ōishi (Minami Hamabe) and the orphaned girl she cares for, Akiko (Sae Nagatani). Though he has the makings of a traditional nuclear family, Shikishima is plagued by survivor’s guilt, leading to some truly stellar acting scenes from Kamiki, who rightfully deserves all the critical attention he has been getting. Despite being a Godzilla film, this is ultimately Shikishima’s story, and Kamiki is in practically every scene of the film. Fortunately, he is more than up to the task of carrying the pathos of the picture from one heartbreaking scene to the next in his every haunted expression and downcast eyes.5 Shikishima struggles to make any sort of meaningful connection with people, walking about with an albatross around his neck that is literalized in the form of a giant mutated prehistoric creature.

Outside of Gareth Edwards’s 2014 Godzilla, few films in the series have taken the subject matter of a giant lizard monster with atomic breath with such straight-faced seriousness since the original, and none have seen fit to turn back the clock and explore the mood of post-war Japan with such detail. What makes Godzilla Minus One work as well as it does is writer/director Takashi Yamazaki’s understanding that Godzilla, as a character, works best as a metaphor for something, and that something needs to be personal for the characters involved. Through all the iterations and redesigns, Godzilla is one of cinema’s most versatile creations, capable of goofiness as easily as seriousness. But the films of the series that standout as genuine “cinematic achievements” are those that position Godzilla as Yamazaki does.6

In Gojira, the character is the sum of a destroyed nation’s fears. In Edwards’s American adaptation, Godzilla is nature itself unleashed against the meddlings of curious and destructive humans. In Michael Dougherty’s 2019 sequel to that film, Godzilla is, perhaps oddly, a very pronounced Christ-type and mankind’s salvation. Now, in Yamazaki’s film, Godzilla becomes the embodiment of one man’s grief and guilt, a nightmare given shape and brought into reality. This idea is brought out in one of the film’s most powerful scenes, wherein Shikishima, sitting in the desolation of a kind of post-apocalyptic hellscape, wonders if he somehow died in the war, and everything that was happening was simply the final, painstakingly long dream of a dying man.

The way Hollywood operates these days seems to suggest that the bigger, louder, more special effects-driven approach makes the box office pop. Less drama, more cheap emotion (remember, folks, J. R. R. Tolkien had a word for that feeling “on your left” evokes long before it was ever uttered in Avengers: Endgame) and action apparently equals a larger box office return. Perhaps ironically, by anchoring Godzilla Minus One with real emotions and minimal SFX thanks to a shoestring budget (the equivalent of less than $15 million USD — practically a low budget film), Yamazaki now has a bona fide hit on his hands.

At time of writing, Godzilla Minus One has made over $50 million, more than making back its under $15 million budget at the American box office alone, shattering many domestic records related to foreign films.7 The film has also received international critical acclaim, with Yamazaki winning for Best Director at Japan’s 48th Hochi Film Awards, and the movie being a finalist for the Special Effects category at the upcoming Oscars. Comscore’s Paul Dergarabedian compared Godzilla Minus One to recent box office hits Oppenheimer, Barbie, and Sound of Freedom, setting them against Disney’s latest big-budget flops like The Marvels and Warner Bros.’ The Flash, to suggest that audiences are not so much fatigued by any one property or character (again, the Godzilla franchise has this film in theaters, a television series currently airing, and another major blockbuster coming out in the next year) but by lazy moviemaking.8

Life Is Worth the Living. Despite its serious tone and darker subject matter, Godzilla Minus One is a film ultimately about life itself. The characters criticize Japan’s government for how little the country’s leaders seemed to care about human life during the war years, specifically pointing out the lack of ejector seats in their fighter planes (this is actually a major plot point in the story). Though crippled by survivor’s guilt, Shikishima must find a reason to live across the film’s two hour runtime, his story becoming a poignant and important reflection on the value of human life, and finding a purpose even in the midst of chaos and destruction. His interactions with Noriko and Akiko plant the seeds of a renewed sense of purpose, while his encounters with Godzilla are emblematic manifestations of his inner turmoil, making the monster an integral part of the narrative’s exploration of grief and guilt.

Focusing on character development, narrative depth, and a more restrained use of special effects, Godzilla Minus One reasserts the potential for the series to be a vehicle for sincere storytelling. The cultural apologist can take hold of the film’s most prominent themes (guilt, absolution, and the sanctity of human life) quite easily, and the nuanced portrayal of Shikishima’s journey from a slough of despond is an engaging and relatable arc that anyone who has been a Christian for more than a day can understand to some degree.

The importance the film puts on the intrinsic worth of each individual, even amidst the horrors of war and personal despair, provides a solid basis for the cultural apologist to begin having discussions that steer one toward Christ. And the film’s critique of the government’s apparent disregard for human life during wartime, illustrated through Shikishima’s gradual recognition of his own worth and the value of those around him, is particularly cutting — especially when a subject like abortion remains such a salient cultural topic today.

In eschewing the typical bombast of many of its predecessors, Godzilla Minus One carves a niche for itself within the series’ legacy, extending its relevance far beyond the confines of the genre of kaiju films it helped to codify. Who would have thought that, in 2023, returning the iconic monster to his Second World War roots with minimal special effects and a healthy dose of human drama would produce one of the most thoughtful and resonant films in the franchise’s seventy-year history?

Cole Burgett is a graduate of Dallas Theological Seminary and the Moody Bible Institute. He teaches classes in systematic theology and Bible exposition and writes extensively about theology and popular culture.

NOTES

- Sheryl Wudunn, “Tomoyuki Tanaka, the Creator of Godzilla, Is Dead at 86,” New York Times, April 4, 1997, https://www.nytimes.com/1997/04/04/movies/tomoyuki-tanaka-the-creator-of-godzilla-is-dead-at-86.html.

- Logan Nye, “Godzilla Exists Thanks to This Japanese Prisoner of War,” We Are the Mighty, November 7, 2022, https://www.wearethemighty.com/popular/godzilla-ishiro-honda-ww2-infantry/.

- Keith Phipps, “Godzilla and the Age of Atomic Anxiety,” The Dissolve, May 6, 2014, https://thedissolve.com/features/movie-of-the-week/547-godzilla-and-the-age-of-atomic-anxiety/.

- Editor’s note: Wikipedia helpfully explains that “the Godzilla film series is broken into several different eras reflecting a characteristic style and corresponding to the same eras used to classify all kaiju eiga (monster movies) in Japan. The first, second, and fourth eras refer to the Japanese emperor during production: the Shōwa era, the Heisei era, and the Reiwa era. The third is called the Millennium era, as the emperor (Heisei) is the same, but these films are considered to have a different style and storyline than the Heisei era.” “Godzilla (Franchise),” Wikipedia, last edited December 19, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Godzilla_(franchise).

- Jacob Slankard, “‘Godzilla Minus One’ Finally Makes Us Care about the Humans,” Collider, December 8, 2023, https://collider.com/godzilla-minus-one-humans/.

- Takasi Yamazaki, quoted in in Charles Pulliam-Moore, “The Influences of Godzilla Minus One Go Beyond the Atom Bomb,” The Verge, December 4, 2023, https://www.theverge.com/23984534/godzilla-minus-one-interview-takashi-yamazaki.

- Robert Pitman, “7 Box Office Records Broken by Godzilla Minus One,” ScreenRant, December 9, 2023, https://screenrant.com/godzilla-minus-one-movie-box-office-records-broken/#godzilla-minus-one-is-the-biggest-domestic-opening-for-a-foreign-language-movie-in-2023.

- Paul Dergarabedian quoted in Saba Hamedy, “Rave Reviews and Box Office Records: How ‘Godzilla Minus One’ Took the U.S. by Storm,” NBC News, December 8, 2023, https://www.nbcnews.com/pop-culture/godzilla-minus-one-box-office-movie-success-hollywood-rcna128389.