This article first appeared in the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL, volume 36, number 05 (2013). The full text of this article in PDF format can be obtained by clicking here. For further information about the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL go to: http://www.equip.org/christian-research-journal/

I have been on my guard

not to condemn the unfamiliar

For it is easy to miss Him

at the turn of a civilization.

—David Jones

A soccer mom walks into Books-A-Million in search of manga….Reads like the opening line of a good joke, right? But for her, or for anyone who has never encountered the world of manga, there’s nothing comical about it. In fact, it is the very real and present world her teenager inhabits.

She’s familiar with the mantra, “Mom, I’ll be in the manga section when you’re ready to go!” She knows that when he’s not doing the things he must do, he’s doing the things he can’t help but do: reading three or four different graphic novel collections simultaneously and obsessing over when the latest issue will land on the shelf. Today, however, instead of grabbing her caffé latte and turning left into the familiar rows of cookbooks and magazines, she’s making a detour, on her guard not to condemn, but to explore, the unfamiliar.

Just past a few rows of Science Fiction and another row of Adventure Games, Star Wars, and Graphic Novels, she turns the corner and comes headlong into a handful of boys and girls, men and women, gathered before a long row of manga graphic novels. Some sit cross-legged on the floor. (She knows what that’s like, being so eager to find a certain book on the shelf and finally getting hands on it, then dropping to the aisle between shelves to start reading!) Others sink into comfy chairs or sit on the benches. All are engrossed, including her son, who is right in the middle of it all, with a book in hand and a few others in a stack next to him. “What’s the draw? Why does he feel so at home here?

What is manga anyway? Is it trash or treasure? Would Jesus read manga? For goodness’ sake, I don’t even know how to pronounce the word!” Questions abound for her and because I suspect she’s not the first to probe for answers with either the best or worst of intentions, I’ve decided to attempt a very brief explanatory exposé. Oh, and by the way, it’s pronounced “MAHN GAH,” like the “a” in “father.”

“SCARAMOUCHE, SCARAMOUCHE, WILL YOU DO THE FANDANGO?”

During the summer of 1973, when I was ten, Brian and Eddy, my two best friends in the world, gave me the ultimatum of either sitting long hours cross-legged on Brian’s bedroom floor (without bathroom breaks) reading comics, or taking a hike. I was being initiated into their sacred space!

Between placing the latest issue of The Amazing Spider-Man in its protective sheath for eternal preservation and planning our next trip to James Drug Store to scour the comic book rack (singular) for the next issue, we would listen to and memorize Queen’s “Night at the Opera” album, read Famous Monsters magazine, and make 8mm Claymation movies. We knew “Bohemian Rhapsody” by heart years before Wayne’s World sent it viral on Saturday Night Live. We were nerds when nerd wasn’t cool!

To Marvel purists then, DC Comics were anathema. Fantastic Four. Daredevil. The Incredible Hulk—we turned their covers over slowly and with a sacred cadence as we read each word on each page, careful to evoke the power of the comic genre itself. The ink, the colors, the onomatopoeia1 (on-uh-mat-uh-pee-uh = “Boom!” “Thud!” “Ka-Pow!”). We knew that, like the atom, great power was locked into those simple lines and boxes, great power only releasable by the reader’s mind.

Sweet summers flew by, and in the summer of 1977, Eddie brought manga into our sacred chamber, and time stood still. It was like seeing a dead body for the first time. Shock and awe! First of all, the little book was unflopped. That is, manga reads right to left. The front is the back. You have to turn it over to begin reading. Unlike English, Japanese is read right to left, so Japanese comics are read in reverse order from the way our precious Spider-Man was typically read. This was cause enough to abandon the experiment.

Yet because Eddie’s mom owned a little comic book shanty on the edge of town and he worked weekends there (we thought him wise in the ancient ways of “comic-dom”) and because he convinced us we were about to enter a world where angelic art and a devilish story intertwined, we caved. It turns out that Marvel and manga were not two mutually exclusive worlds. We were captured and enraptured, even that first day, and vowed to love them both.

UNDERSTANDING MANGA

Because Scott McCloud’s initial experience with manga in 1982 is similar to Brian’s, Eddie’s, and my own, and because graphic novelist and creator of Sin City, Frank Miller, called him “just about the smartest guy in comics,” and, too, because he’s written three of the best books2 anyone could read on comics, graphic novels, and manga, I default to his exceptional explanation of the power of the visual storytelling manga generates.

The only difference between his and my initial experience was that I was a fourteen-year-old high-school nerd, and he was a twenty-two-year-old recent college graduate who had just landed a job at DC Comics (“heaven forbid!”) at New York’s Rockefeller Center, just blocks from one of the biggest Japanese bookstores in America, known as Kinokuniya. He would spend his lunch hour every day rifling through the manga shelves reading the pictures panel-by-panel, cover-to- cover, poring over the visual storytelling techniques rarely seen in American comics.

At least eight of the manga storytelling techniques McCloud found on Kino’s shelves were almost completely absent from the mainstream superhero comics he also read:

- Iconic characters: simple, emotive faces and figures that led to a kind of profound reader identification.

- Genre maturity: understanding of the unique storytelling challenges of literally hundreds of different genres including sports, business, horror, and so on.

- Sense of place: environmental details that trigger sensory memories and, when contrasted with iconic characters, lead to the “masking effect” (where the reader essentially becomes one with the character and enters into the sensually stimulating world the character inhabits).

- Character designs: wildly different face and body types and the frequent use of recurring archetypes.

- Wordless panels: combined with aspect-to-aspect transitions between panels; prompting readers to assemble scenes from fragmentary visual information.

- Small real-world details: appreciation for the beauty of the mundane and its value for connecting with readers’ everyday experiences—even in fantastic or melodramatic stories.

- Subjective motion: using streaked backgrounds to make readers feel like they were moving with a character, instead of just watching motion from the sidelines.

- Emotionally expressive effects: expressionistic backgrounds, montages, and personalized caricatures—all aimed at giving readers a window into what characters are feeling.

McCloud observed how all of these characteristics contributed to the manga experience in different ways, but as he studied his own reaction to manga and looked into manga’s role in Japanese society, he noticed a common theme, as if all the techniques were being deployed toward a single purpose: to amplify the sense of reader participation in manga, a feeling of being a part of the story, rather than simply observing the story from afar.

A HISTORICAL SNAPSHOT OF MANGA

In 1965, Tetsuwan Atom (Mighty Atom) was the first weekly cartoon made for Japanese television, and it was introduced to the American market as Astro Boy that same year. America’s love affair with Japanese pop culture began in the 1950s with monster movies such as Godzilla, continued into the 1960s with television shows such as Speed Racer and Gigantor, the 1970s with video games such as Pac-Man and Space Invaders, the 1980s with intricate toys such as Voltron and Transformers, and into the 1990s with the Mighty Morphin Power Rangers. Yet despite the popularity of these movies, toys, and shows, Japanese manga didn’t really catch on until the 1980s when translated manga began showing up in U.S. comic book and book stores. The first blockbuster manga in America was the Samurai Action title Lone Wolf and Cub, in 1987. It sold one hundred thousand copies a month, compared to the comic X-Men’s four hundred thousand copies. Around the same time, however, Japanese manga producers opened publishing houses in New York and San Francisco and began large-scale distribution in America.

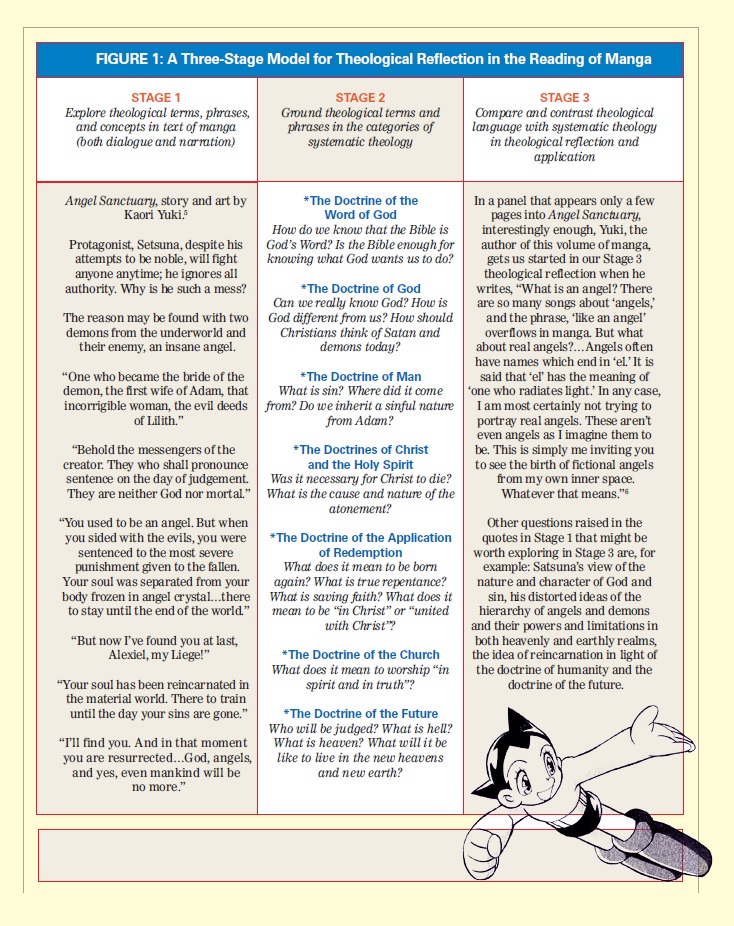

FIGURE 1: A Three-Stage Model for Theological Reflection in the Reading of Manga

Over the past decade, manga has gone from accounting for one-third of the $70 million dollar graphic novel industry to claiming almost two-thirds of what is now a $550 million movement. According to Senior Editor Jason Thompson at manga powerhouse publisher VIZ, “What 20 years ago seemed too culturally specific for export has become another extension of Japan’s soft power, what journalist Douglas McGray calls its ‘Gross National Cool.’ Manga has achieved liftoff.”3

MANGA AS THEOLOGICAL REFLECTION

Theological reflection4 enables us to ascertain God’s presence and action in the world and allows us to reflect on ministry practice in light of the Christian heritage (Scripture and tradition) and the cultural context. With this in mind, one can attempt to connect the world of manga with the Christian worldview one holds by linking his or her story with others’ stories and with God’s.

This kind of theological reflection helps us become aware of how we are actually living compared to how we aspire to live; theological reflection helps us see and heal the disconnect between our beliefs and our practice. Space does not allow for a detailed explanation of the importance of exploring systematic theology for building a strong Christian foundation for all of life. Likewise, theological reflection, when practiced, proves a powerful tool to connect the narrative of a secular genre such as manga to this foundation of faith.

For the soccer mom whose questions prefaced this brief exploration into the world of Japanese comics known as manga, the twin disciplines of both also allow her a conversational bridge she might easily cross, now that she’s braved the crowded aisle of the manga section at Books-A-Million. The three-stage model for theological reflection I offer here is my own. There are many more from which to choose.

May the latest issue come early and may there always be a comfy reading chair for you as you navigate the crowded aisles among the rows of manga!

C. Wayne Mayhall, MACT, MSHE, Ed.D. (ABD), is an adjunct professor of philosophy at Liberty University and adjunct professor of philosophy and theology at Limestone College. A former associate editor of the Christian Research Journal, he continues to collaborate with CRI.

NOTES

- Onomatopoeia: the formation of a word, as cuckoo, meow, honk, or boom, by imitation of a sound made by or associated with its referent. The use of imitative and naturally suggestive words for rhetorical, dramatic, or poetic effect.

- You couldn’t go wrong adding these to your reading list (all titles by Scott McCloud): Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art (New York: First HarperPerennial, 1994); Making Comics: Storytelling Secrets of Comics, Manga and Graphic Novels (New York: HarperCollins, 2006); Reinventing Comics: How Imagination and Technology are Revolutionizing Art Form (New York: HarperCollins, 2000).

- Jason Thompson, “How Manga Conquered the U.S., a Graphic Guide to Japan’s Coolest Export.” Wired Magazine 15, 11. Available online at http://www.wired.com/special_multimedia/2007/1511_ff_manga.

- There are many wonderful books and articles on theological reflection and systematic theology available for the seeker. I offer two that I have found invaluable with both my own exploration and with my patients (as a hospital chaplain) and students (as a college professor). They are The Art of Theological Reflection by Patricia O’Connell Killen (New York: Crossroad Publishing Company, 1994) and Systematic Theology: An Introduction to Biblical Doctrine by Wayne Grudem (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1994).

- Kaori Yuki, Angel Sanctuary, vol. 1 (San Francisco: VIZ Media, LLC, 2004).

- Angel Sanctuary, 29.