Cultural Apologetics Column

This article was published exclusively online in the Christian Research Journal, Volume 46, number 03 (2023).

When you support the Journal, you join the team of to help provide the resources at equip.org that minister to people worldwide. These resources include our ever growing database of over 1,500 articles, as well as our free Postmodern Realities podcast.

Another way you can support our online articles is by leaving us a tip. A tip is just a small amount, like $3, $5, or $10 which is the cost for some of a latte, lunch out, or coffee drink. To leave a tip, click here

Film Review

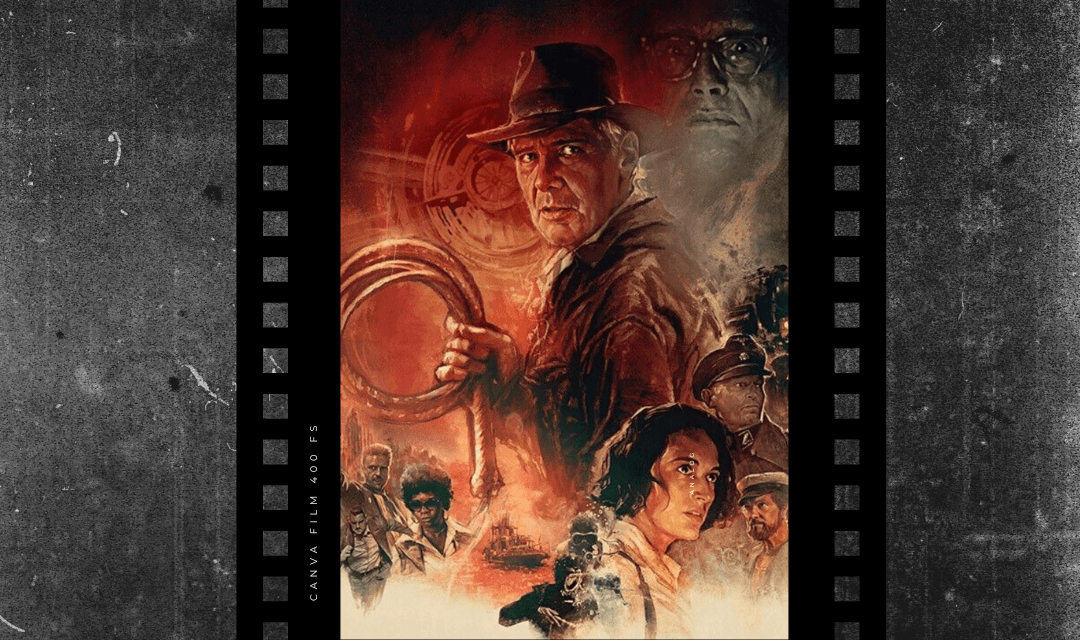

Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny

Directed by James Mangold

Written by Jez Butterworth, John-Henry Butterworth, David Koepp, and James Mangold

Distributed by Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures

(PG–13, 2023)

**Editor’s Note: This article contains spoilers for Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny.**

“If adventure has a name, it must be Indiana Jones.” So reads the tagline on the poster for Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984), the sequel to 1981’s Academy Award-winning smash hit, Raiders of the Lost Ark. A throwback to the classic film serials of the early twentieth century, Raiders brought together young filmmaking rock stars Steven Spielberg and George Lucas to introduce audiences to one of pop culture’s most enduring film icons. From the fedora to the whip, the silhouette of the roguish archaeologist portrayed to cunning perfection by Harrison Ford loomed large. Every nerve-jarring gunshot, every bone-crunching punch, and every harrowing escape thrilled audiences for the better part of a decade as they followed the globe-trotting exploits of Dr. Henry “Indiana” Jones Jr. across three films, concluding with 1989’s Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. For the better part of that decade, the Temple of Doom tagline was very right.

The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles (1992–1996) saw Sean Patrick Flanery and Corey Carrier play younger versions of Jones in an Emmy Award-winning television spin-off, but the show never seemed to capture audiences the way the original trilogy had. The filmmaking band got back together in 2008 for Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, a (most would argue) fairly middling entry in the series that failed to recapture the magic of the trilogy — though it is worth noting that returning to the style of those first three films was never the point.1 After Disney acquired Lucasfilm for a whopping $4 billion back in 2012, stewardship of the series passed from George Lucas to Kathleen Kennedy, and the fifth and (for now) final film in the series, Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny, released in 2023, concluding Harrison Ford’s tenure as the titular character.2

Few actors have had the luxury of being able to stick with and develop a character for over forty years, yet there is a sense in which Harrison Ford is Indiana Jones. In many ways, among the pantheon of iconic characters Ford has played over the last half-century (including Han Solo, Rick Deckard, John Book, Jack Ryan, Dr. Richard Kimble), Jones will form the most enduring part of his legacy. Solo alone is engraved upon the flipside of that coin, but according to Ford himself, “he’s certainly a much less interesting character than Indiana Jones. The breadth of his story utility was never extensive. He was the foil between the other more compelling elements of the film [Star Wars], between the sage old warrior and the young hero.”3 In other words, of the actor’s two most significant characters, Jones wins the day by virtue of being able to carry his own story.

And with the release of Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny, that story has been told. Though he will likely be remembered for his gumption and ability to give as good as he gets, what makes Jones a worthwhile character goes beyond whip-smart dialogue and cleverly conceived action set pieces. Jones’s story is as much one of personal growth and finding treasure in the ordinary as it is about punching Nazis in pursuit of lost artifacts. That makes the character and his story worth paying attention to, especially for Christians navigating a culture in which “progress” is heralded as the ultimate goal.

Good Ol’ Fashioned Heroism. Heroes are never going out of style. History and mythology have taught us that time and again. But the kinds of heroes we tell stories about have changed, and well beyond the trappings of cultural differences. If the late twentieth-century produced the anti-hero, the early twenty-first produced the self-conscious hero.4 Embodied by the likes of Tom Holland’s Peter Parker, the ironic protagonist who feels the need to constantly “wink” at the audience has come to dominate the zeitgeist.

Couple this with the fact that changing cultural norms tend to call for reevaluations of traditional masculine (and therefore “heroic”) values, and the result looks something like Gerry Canavan’s article, “The Racist Literary Origins of Indiana Jones,” published by The Washington Post. In this article, Canavan offers a take on the Jones films that suggests the very plot structure of the films themselves is, somehow, inherently racist. Here is how he argues his point:

A brilliant White man, very often a professor, deploys personal reserves of cleverness, resilience and unrelenting determination in the service of exploration, discovery and resource extraction. That narrative template guides these stories even when the author attempts to push back on their ideological implications. Think, for example, about how the Indiana Jones films use the Nazi menace to distract from the fact that our hero is almost always appropriating the treasures of Indigenous or pre-colonial peoples. It’s as if they felt obliged to remind us that there’s always a worse White man, as a sort of alibi. 5

In other words, Canavan argues that the adventure genre, formulated and codified by the likes of H. Rider Haggard and Johnston McCulley (creator of Zorro) — which inspired George Lucas to create the character of Indiana Jones — is built with white hands using the hammers and nails of racist ideologies. This leads Canavan to conclude that “the figure of the Great White Hero feels almost completely used up. In 2023, Marshall College [where Jones works in Dial of Destiny] undoubtedly begins its events with a land acknowledge and has probably scraped Jones’s name off whatever building it was on.” Apparently, if Canavan’s premise is to be believed, the legacy of Indiana Jones is one of racism — sabotaged from the jump because said racism is baked into the warp and woof of the plot structure itself.

According to George Lucas, Indiana Jones was inspired by works from a “whiz-bang” time. “Raiders [of the Lost Ark] owes a lot to the Tarzan books, the Amazing Adventures, the pre-comic-book books of that era.”6 There is no denying that many works in that time were drowned in poorly conceived racial stereotypes — just take a look at some of the covers of pulp magazines and their portrayals of African and Asian characters — it’s pretty horrendous. And Canavan sees the fact that Jones is a character with development as an admission on the part of the filmmakers that there are “problems” with the source material. He explains, “If these influential texts are haunted today by their unavoidable racism, it’s not as if Indy’s creators — who grew up loving these stories — were wholly unaware of the problems with them….Even the original ‘80s films know, on some level, that Jones is a villain in his story.” So, according to Canavan, the fact that Jones has character flaws — necessary for character development — becomes a kind of admission on the part of Lucas, Spielberg, and the rest, that the very stories they are telling are “problematic.”

Nowhere is the possibility of Jones’s development as a character — the thing that makes him interesting, heroic, even — factored into Canavan’s discussion. Consider that Steven Spielberg, director of the first four films, characterized Jones as “not a perfect hero, and his imperfections, I think, make the audience feel that, with a little more exercise and a little more courage, they could be just like him.”7 Interestingly, the “problems” Canavan seems to have with Jones as a character are the very things that one of the character’s creators believes make him a good character — not necessarily a good person. At least, not at first.

Throughout the film series, Jones is known for spouting, “It belongs in a museum!” when speaking of whatever artifact he is searching for. Narratively, however, said artifact rarely ends up in a museum, or even in Jones’s possession. The climax of the films often sees Jones making the decision to relinquish the artifact for any number of reasons — a denial of himself, in a sense. Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, for example, finds Jones conceding that appropriating items of great value to a culture different from the one he knows and understands might not be the right thing to do, so he returns the Sankara Stones to the Indian villagers rather than keep them for himself or use them for his own academic advancement. Academy Award-winner Ke Huy Quan, who portrayed Short Round in the same film, had this to say when asked about the film’s use of the “white savior” trope:

We’re talking about something that was done almost 40 years ago. It was a different time. It’s so hard to judge something so many years later. I have nothing but fond memories. I really don’t have anything negative to say about it. Spielberg was the first person to put an Asian face in a Hollywood blockbuster. Short Round is funny, he’s courageous, he saves Indy’s ass. That was a rarity then.8

It is not that audiences are meant to aspire to Jones’s flaws — those flaws, to Spielberg’s point, are what make him relatable. His heroism thus becomes his willingness to see, admit, and overcome those flaws — as demonstrated by the plots of the stories themselves. The moment in which Jones “denies himself,” Canavan characterizes as part of “the religious conversion narrative,” which he describes as following a “self-obsessed and lonely skeptic, a man of science who has let his career crowd out all other aspects of his life…[who] is granted a momentary gift of grace, which changes his life forever….In this way every Indiana Jones film is really just a genre-swapped version of ‘A Christmas Carol.’”

Or the Indiana Jones films reinforce a baseline morality that has been handed down and codified in myths and fables for thousands of years across the cultural spectrum, from Wu Cheng to Charles Dickens — that selflessness is actually virtuous, and true heroism from an earthly perspective is not perfection, but of putting others above oneself. But these kinds of contextual readings, in which that “momentary gift of grace” is the point of the narrative are lost when all one can see is the skin color of the main character.

A Flawed Legacy. In place of artifacts, Jones frequently ends up with something less tangible, but far more important. In Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, he lets the Holy Grail be lost forever rather than lose another moment with his father (Sean Connery). Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull sees him accepting responsibility as a parent when he learns that he has a son (Shia LeBeouf). And in Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny, he finds an opportunity to reconcile with his estranged wife, Marion Ravenwood (Karen Allen), after the death of their son in Vietnam — hardly the Ghost of Christmas Past. Yet this is where Jones’s story ends, time and again. His legacy is one of giving up and letting go, of finding meaning in the ordinary despite the extraordinariness of his adventures. It is a flawed legacy in the best of terms.

Western culture has moved beyond the hero and the anti-hero, to heroes who are not allowed to have flaws, who must wink at the audience to let us know that the people who are writing them know that it is all make-believe anyway, as if audiences might begin — God forbid — to take seriously the narrative and characters put before them. Astounding (but not entirely surprising) is the pendulum swing from the deconstruction of heroes to the castigating of the heroic altogether.

Of course, this walks hand-in-hand with the redefinition of sin from a real transgression of divine law at odds with a baseline morality to, effectively, “indulgence” or “enjoyable naughtiness.”9 We are not allowed to take flaws in our heroes seriously because we should not take flaws seriously — unless, of course, they are baked into the warp and woof of “plot structures” and never a part of the characters themselves.

Perhaps the real offense of characters like Indiana Jones to modern sensibilities has less to do with the fact that George Lucas grew up reading stories, some of which contained racial prejudices, and more to do with a rethinking of masculinity and heroism in general.10 It is difficult to produce heroic figures in a culture that has eroded its ability to recognize personal responsibility and frowns upon the adjustments of one’s behavior in light of that responsibility.

To illustrate the point, here is what the apostle Paul characterizes as the “impure lusts of the heart” (see Romans 1:24), which were the natural consequences of mankind’s collapse into sin:

For this reason God gave them over to degrading passions; for their women exchanged the natural function for that which is unnatural, and in the same way also the men abandoned the natural function of the woman and burned in their desire toward one another, men with men committing indecent acts and receiving in their own persons the due penalty of their error. (Romans 1:16 –27 NASB 1995)

Ask yourself how well this description of — let’s use a milder term than what Paul calls “degrading passions” here, for argument’s sake — “flaws” measures up to the standards of modern culture, and one can begin to see the redefinition of sin at work. I will venture onto a limb and suggest that, in the first half of the twenty-first century, Paul would not be considered an “ally,” despite his preaching a gospel in which literally anyone — especially the people he is characterizing here (read the rest of Romans) — could come to saving faith in Jesus Christ.11

If characters like Indiana Jones, who recognize their flaws as human beings and adjust their thinking accordingly — regardless of their melanin levels — are “old fashioned” or “used up,” then what kind of stories do we tell, as a culture? That heroism is flawless? That selfishness and personal responsibility are meant to be winked at and taken with a healthy dose of cynicism and irony? Which of these principles do we want to instill in our children?

In another universe (since “multiverses” are all the rage nowadays), Jones ignores his father’s pleas and falls to his death reaching for the Holy Grail — there’s a lesson there. In another, Jones keeps the Sankara Stones for himself, robbing a culture of its sacred treasure and becoming consumed with power — there’s a lesson there, too. In yet another, he ignores his son and probably ditches Marion to live out his repressed fantasies with Harold Oxley (John Hurt). The ridiculousness belies the point. After forty years of storytelling, what makes Jones “old fashioned” is not the fact that he is white, but exactly what Spielberg — one of his creators — says: Indiana Jones is “not a perfect hero.”

That category is reserved for one individual in history — and His story is told in the pages of Scripture.

Cole Burgett is a graduate of Dallas Theological Seminary and the Moody Bible Institute. He teaches classes in systematic theology and Bible exposition and writes extensively about theology and popular culture.

NOTES

- See “TF Interview: George Lucas,” in Total Film, May 2008. The original trilogy, set during the 1930s, was meant to reflect the adventure serials popular during that time. Kingdom of the Crystal Skull was conceived by Lucas as an homage to 1950s science fiction B-movies — a different genre and style of filmmaking altogether.

- “Disney to Acquire Lucasfilm Ltd.,” The Walt Disney Company, October 30, 2012, https://thewaltdisneycompany.com/disney-to-acquire-lucasfilm-ltd/.

- Harrison Ford, qtd. in “Star Wars: Episode VII: Harrison Ford and Han Solo Bury the Lightsaber,” Entertainment Weekly, May 7, 2014, https://ew.com/article/2014/05/07/star-wars-episode-vii-harrison-ford-and-han-solo-bury-the-lightsaber-essay/.

- See Subby Szterszky, “Heroes and Anti-heroes: Shifting Ideals in a Shifting Culture,” Focus on the Family, https://www.focusonthefamily.ca/content/heroes-and-anti-heroes-shifting-ideals-in-a-shifting-culture.

- Gerry Canavan, “The Racist Literary Origins of Indiana Jones,” The Washington Post, June 28, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/books/2023/06/28/indiana-jones-racism-books/.

- George Lucas, quoted in “The Marking of Raiders of the Lost Ark,” The Guardian, July 23, 1981, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2021/jul/23/the-making-of-raiders-of-the-lost-ark-film-1981.

- Steven Spielberg, quoted in Jim Windolf, “Q&A: Steven Spielberg,” Vanity Fair, December 2, 2007, http://www.vanityfair.com/culture/features/2008/02/spielberg_qanda200802.

- Ke Huy Quan, qtd. in Ann Lee, “I didn’t have a single audition for a year’: Goonies and Indiana Jones child star Ke Huy Quan on finding fame again,” The Guardian (Nov. 21, 2022), https://www.theguardian.com/film/2022/nov/14/ke-huy-quan-goonies-indiana-jones-asian-actors-everything-everywhere-all-at-once.

- See Francis Spufford’s discussion of the term “sin” in “The Crack in Everything,” in Unapologetic: Why, Despite Everything, Christianity Can Still Make Surprising Emotional Sense (London: Faber and Faber, 2012), 24–53.

- See this gem bemoaning Captain America’s “heterosexual virility”: Joanna Robinson, “Is This the One Flaw in the Otherwise Great Captain America: Civil War?” Vanity Fair, May 8, 2016, https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2016/05/captain-america-civil-war-steve-rogers-sharon-carter-bucky-barnes.

- This is not to say that every individual homosexual inclination is God “punishing” the person who feels that inclination because of sin. Paul is painting in broad strokes here, and very likely has the early chapters of Genesis in mind as his point of reference. However, one is going to have to perform an astounding feat of hermeneutical gymnastics if they hope to argue that the characterization of homosexuality in the biblical texts — both in Genesis, which Paul is referencing, and in Paul’s own thought, which he is arguing — is one that is somehow good in the sense of righteousness. One might not agree with the text, but let us be very wary of redefining the text’s “plain meaning” in an effort to fit within the framework of modern sensibilities.