This article first appeared in the News Watch column of the Christian Research Journal, volume 30, number 1 (2007). For further information or to subscribe to the Christian Research Journal please click here.

The nickname JuBus is humorous and concise, even a bit self‐effacing. It refers to a large demographic of Jews who have shown an interest in Buddhism, whether by incorporating meditation into their synagogue or home rituals or by becoming Buddhist gurus. A short list of well known JuBus—who sometimes also call themselves BuJus—includes actor Orlando Bloom, the late poet Allen Ginsberg, actress Goldie Hawn, and psychiatrist and author Daniel Goleman.

In his book The Jew in the Lotus (Harper Collins, 1994), Rodger Kamenetz observed the widespread influence of JuBus by the early 1990s. He described JuBus as being part of a “more innovative and less stable” Buddhism that “draws primarily on non‐Asian Americans.”

“In the past twenty years, [JuBus] have played a significant and disproportionate role in the development of this second form of American Buddhism,” Kamenetz wrote. “Various surveys show Jewish participation in such groups ranging from 6 percent to 30 percent. This is up to twelve times the Jewish proportion of the American population, which is 2 ½ percent.”

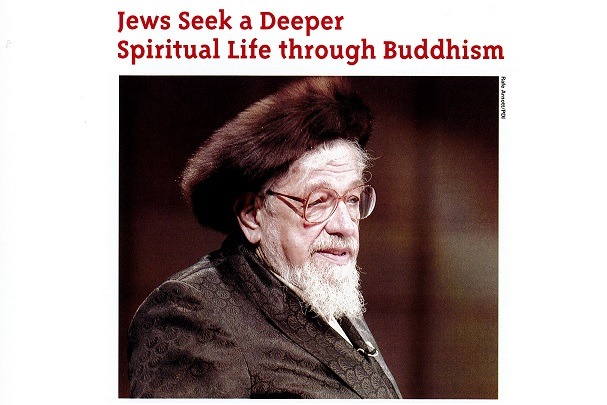

If synagogue‐attending JuBus have patriarchs, one would be Rabbi Zalman Schachter‐Shalomi. He was ordained by the ultra‐Orthodox Lubavitcher Hasidim, but eventually formed a new movement now known broadly as the Jewish Renewal.

Schachter‐Shalomi’s interests in interfaith dialogue are broad. “When I’m teasing people I say I had a Catholic period, a Protestant period, and a Sufi period,” he told the Christian Research Journal. “I think that Judaism would not be a good thing for Eskimos. I keep saying each religion is a vital organ of the planet.”

The rabbi is not troubled when people who were born Jewish devote more of their energy to Buddhism than to Judaism. “I’m not in charge of the universe,” he says. “I think God knows what God is doing.

Schachter‐Shalomi believes the worship in American synagogues after World War II left many Jews feeling spiritually empty. “They largely became a Jewish denomination of liberal Protestantism,” he said. “There were many people who were turned off by the legalism and ritual strictures.”

The Holocaust nearly destroyed Judaism’s oral traditions of mysticism, he said, leaving Jews to seek deeper spiritual experiences from sources outside of Judaism. The Holocaust had another effect, he said, creating “recycled souls” who returned to Earth as spiritually hungry Baby Boomers. (Yonassan Gershom explores this theory at greater length in the book Beyond the Ashes: Cases of Reincarnation from the Holocaust.)

Schachter‐Shalomi acknowledges that Jewish belief in reincarnation may sound foreign to traditional believers. He says exoteric believers, those who are concerned with the externals of faith, object more readily to this idea than do esoteric believers.

Varying understandings of the teachings in Judaism and Buddhism lead to an intriguing moment in The Jew in the Lotus when Rabbi Joy Levitt describes her discussion with Thubten Chodron, a Jew who became a Tibetan Buddhist nun: “My sense of where Chodron and I divided possibly has to do more with our psyches and upbringing. She found it impossible to accept the fact that when you die you’re dead, that’s it. And I never had that question. I don’t know why I didn’t have that question and she did. And she found that question resolved in Buddhism, which is when you’re dead, you’re not dead.”

The movement Schachter‐Shalomi helped create finds an institutional expression through ALEPH, the Alliance for Jewish Renewal. Susan Saxe, ALEPH’s chief operating officer, says the organization does not actively participate in syncretism but is not as troubled by syncretism as more traditional Jews would be.

“You go take a yoga class, nobody’s asking you to bring a sacrifice to a guy with the head of an elephant. If you see Jews meditating, we’re not practicing Buddhism.” she told the Journal.

“We don’t object to importing the vanilla pieces of other people’s traditions,” she said. Saxe said the movement strives to affirm Jews who find a deeper spiritual path in Buddhism. “I sometimes say Jews have done a spiritual cardiac bypass through Buddhism,” she said.

Saxe echoes Schachter‐Shalomi’s observation that postwar Judaism often was stripped of chanting, dance, and contemplative prayer. “Many, many people don’t know that Judaism has a long contemplative tradition,” she says. “What we don’t know is that we all have treasure buried in our own backyard.”

When individuals and congregations call ALEPH, they are usually pursuing a specific discipline, such as a meditation technique, rather than dabbling in Buddhism. If they were interested in meditation, Saxe says, “We would say, did you know we have that in our own tradition? We wouldn’t send them a Buddhist” as a guest speaker.

To Buddhism and Back Again. Dr. Nathan Katz does not remember why, but by the time he was nine he was fascinated with India. “All my friends collected American or Israeli stamps. I collected stamps from India.”

When Katz made his first trip to India he was overwhelmed by the hot climate, the very spicy food, the poverty, the beggars, and the street odors. He thought he hated it and would not return. Months passed, however, and Katz also realized that India had imprinted itself on his soul and that he would return after all. “I had some experiences that I would have to describe as spiritual,” he told the Christian Research Journal.

Katz, who today is a religion scholar at Florida International University in Miami, grew up in a traditional but not especially observant Jewish home. “We didn’t learn, we didn’t study like Orthodox Jews usually do,” he says. “I sort of left Judaism for a decade and a half, maybe two.”

Katz immersed himself deeply in Buddhist practice during his years away from Judaism. A few photos on Katz’s Web site help tell his story. In 1976 he stands in sandals, wearing a bushy beard, alongside the Venerable Nyanapokika Mahathera, a Buddhist monk. Katz smiles slightly, and the monk looks somber but kind.

In 1980 Katz stands with his bushy beard again, this time next to the Beat poet Alan Ginsberg. Both hold their forefinger and thumb together in a gesture of heightened consciousness.

A third picture shows Katz in Miami Beach, his beard far less bushy now, joined by his wife and son. They all smile broadly and Katz wears a dapper white hat.

Katz was one of several Jews, including Rabbi Schachter‐Shalomi, who were invited to an audience with the Dalai Lama in 1990. The exiled leader of Tibetan Buddhists had expressed interest in how Jews preserved their faith during so many centuries of exile, and he wanted to learn from them.

Katz later invited the Dalai Lama to visit Florida International University, which he did in both 1995 and 2004. Katz and the Dalai Lama first met in 1973, while Katz was studying Tibetan language in India.

Today Katz retains a few disciplines he learned during his sojourn through Buddhism, including mindful meditation. Katz describes mindful meditation in easily accessible terms: Imagine you’re in traffic and facing the usual agitations of a weekday commute. Normally you might fume silently, mutter about the skills of neighboring drivers, or even show anger toward them. In mindful meditation, you instead begin to observe yourself—your breathing, your thoughts, your actions. “Mindfulness creates a gap between impulse and action,” he said. Katz does not continue practicing anything, such as visualization, that he believes would place him in conflict with Torah.

Katz found, during his years in Buddhism, that the practices worked for him, but he also was struck that many of his teachers pointed him back to his Judaism. A Tibetan lama at one meditation retreat advised Katz simply to observe Shabbat as his meditation exercise for the day.

In a dharma talk he delivered in France in 1998, the acclaimed Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh of Vietnam discouraged people from leaving the faith of their childhood or family heritage:

My friends encouraged me to lead retreats, where so many people have learned mindfulness, and I have never said, “Please give up your tradition to follow me.” I say, “If you are Jewish, please do not abandon your Jewish roots. You can study Buddhism with me, but that will help you to go back to Judaism and discover the jewels in Judaism, that may have been covered up by layers, so that you haven’t seen them. If you are Christian, please do not abandon your Christian roots, do not abandon your Christian ancestors.” You are a lion, and you don’t want to be a monkey. A lion can only be happy when it is a lion. Although it can learn the wonderful things that a monkey does, it cannot be really happy when it is cut off from its roots, when it is cut off from its lion lineage.

A Filtered Buddhism. Katz understands the attractions of Buddhism, at least as it’s popularly understood, for Western Jews. Buddhism is nontheistic, so “it does not have a rival position about God” and is perceived as noncontradictory to monotheistic Judaism. Buddhism is perceived as unencumbered by ritual, placing a direct emphasis on practice rather than theory. Katz emphasizes the words “perceived as,” stressing that Westerners sometimes see Buddhism as they want to see it.

“What we get in the West is a sort of exported, refined Buddhism,” Katz says. “But it is also a religion like any other.”

What brought Katz back to Judaism, and gave him a more passionate involvement in it than his youth provided, was encountering a community of Orthodox Jews in Cochin, India. He first saw these fellow Jews while on vacation, but was so taken by them that he returned to live with them for a year to use the participant‐observer method of religious study.

Katz remembers that as he completed his year of study and left the community, he and his wife headed for a restaurant, where he was eager to eat shrimp after a year of eating kosher. He discovered, however, that his renewed connection with Orthodox Judaism would not allow him to eat shrimp any longer.

“I found in Judaism what I found in Eastern traditions,” Katz says, “but in what we would call ’haimish,’ or a more homely way.” In Orthodoxy, Katz says, he has found a profound sense of community.

Katz reserves judgment about Jews whose Judaism seems mostly eclipsed by their Buddhism. “It’s not over till it’s over. You don’t know about a person’s spiritual path until it’s completed,” he said. “I cannot guarantee someone will return, but I can guarantee that you cannot force someone to return.”

What might his friend Allen Ginsberg think about the Nathan Katz who now gives a public lecture titled “From BuJu to OJ” (for Orthodox Jew)? Katz believes Ginsberg might consider him atavistic.

Katz encourages his students to engage spiritual topics from a wide variety of sources. He believes people are divided less by the world’s major religions than by conservative and liberal differences about their doctrines.

How does he propose helping those sides understand each other better? One way would be through film. Katz must be one of the few Orthodox Jews in America who urges people to see both The Passion of the Christ and What the #$*! Do We Know!? “There’s something of value in each of these films,” he says, “and you can’t reconcile them, Lord knows.” — Douglas LeBlanc

Side Bar:

One vigorous critique of JuBus comes from Rabbi Yonah Bookstein, thirty‐seven, campus rabbi for Hillel chapters in Long Beach and Orange County, California. “Buddhism is antithetical to Jewish practice and belief. A basic understanding of the Torah’s prohibitions of idolatry, deism, and asceticism rule out any kosher involvement with Buddhism, its teachers, proponents, and practice. Those practitioners that claim no inherent conflict are simply ignorant,” Bookstein writes in a Weblog post titled, “Don’t Let The JuBus Fool Ya…Buddhism is Treif [not kosher].” He continues:

What attracts Jews to Buddhism are kernels of wisdom that G‐d planted there. Why did G‐d do this? Hashem planted those kernels in order to test us. The popularity of Buddhism, the Dalai Lama, and Buddhist tchachkes [trinkets] challenge each and every Jew to learn about their own heritage. Torah, Kabbalah, and ancient Jewish prayer and meditation, as examples, represent the most unbelievably deep wisdom. Torah teaches how to engage life, the Godly sparks in each person, the nobility of each breath, and the humility to know our place in creation.