Listen to this article (10:58 min)

Cultural Apologetics Column

The following article appeared as an online-exclusive in CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL, volume 48, number 03 (2025).

When you support the Journal, you join the team and help provide the resources at equip.org that minister to people worldwide. These resources include our ever-growing database of more than 2,500 articles and Bible Answers, as well as our free Postmodern Realities podcast.

Another way you can support our online articles is by leaving us a tip. A tip is just a small amount, like $3, $5, or $10, which is the cost of a latte, lunch out, or coffee drink. To leave a tip, click here.

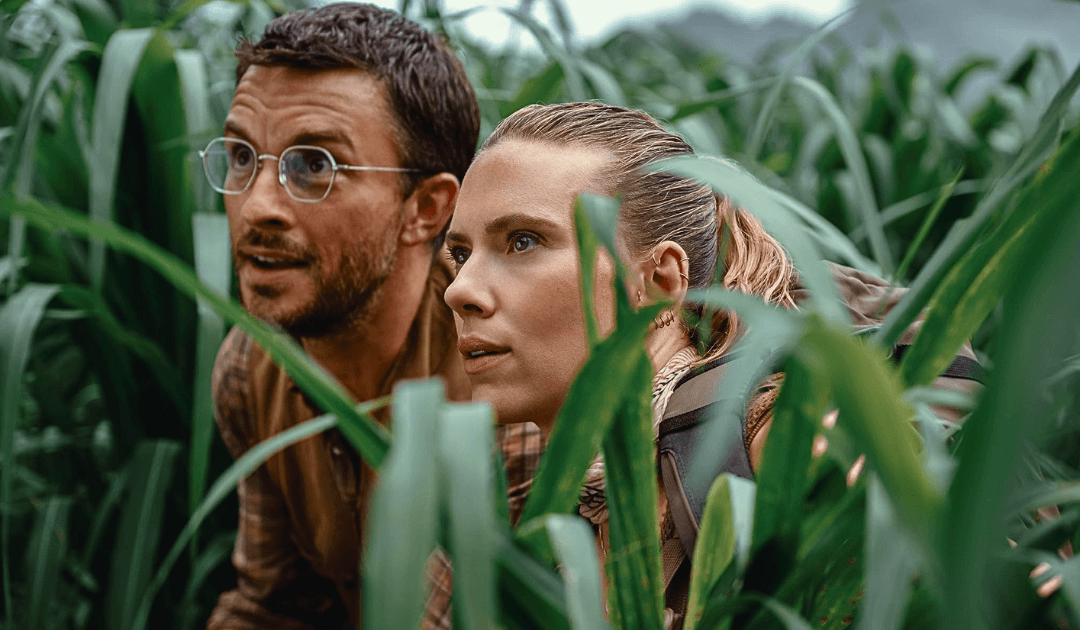

[Editor’s Note: This review contains spoilers for Jurassic World Rebirth and other films in the franchise.]

Jurassic World Rebirth

Directed by Gareth Edwards

Written by David Koepp

Produced by Frank Marshall and Patrick Crowley

Starring Scarlett Johansson, Mahershala Ali, Jonathan Bailey, Rupert Friend, Manuel Garcia-Rulfo, and Ed Skrein

Feature Film (PG–13)

(Universal Pictures, 2025)

When Jurassic Park thundered into theaters in 1993, it tapped into something primal. More than showcasing cutting-edge visual effects or catapulting velociraptors into pop culture stardom, Steven Spielberg’s adaptation of Michael Crichton’s techno-thriller was a cautionary tale about human hubris, scientific overreach, and the illusion of control.1 It was a kind of modern myth, a fable of science gone horribly, horribly wrong — an unhinged Promethean warning of what happens when mankind dares to play God. In resurrecting creatures long consigned to the realm of fossils and fantasy literature, Jurassic Park held up a mirror to the modern age’s unchecked confidence in technology and asked whether the boundaries of creation exist for a reason.

Over the decades, the Jurassic Park films (now a franchise) has undergone its own kind of cinematic speciation, from the wonder and horror of the original trilogy (1993–2001) to the corporate spectacle of the first three Jurassic World sequels (2015–2022). Now, with Jurassic World Rebirth (2025), the series takes yet another step forward — or, perhaps, backward. Rebirth is a fitting title, as the film returns to the philosophical and ethical questions that animated the original: What does it mean to wield power over life itself? Are humans stewards or gods? And when our creations spiral out of control, what is revealed about our own nature?

As cultural artifacts, these films reflect and interrogate our anxieties about science and nature, as well as the limits of human dominion. For the Christian, they churn up the fertile soil of cultural apologetics with those perennial questions about what happens when mankind forgets its place in the created order, and the consequences people are faced with when the reach of modern scientific advancement exceeds its feeble grasp.

More Than Just Dinos. From the very beginning, Jurassic Park was never just about dinosaurs. Following Crichton’s trajectory, Spielberg’s originals were meditations on power and its consequences. The first film presented a kind of Genesis narrative: a paradise engineered by human hands, populated with wonders that soon turned on their creators. The message was clear — when humans transgress natural limits, chaos ensues. This theme is more or less literalized in the film through the character of Ian Malcolm, a chaos theorist portrayed by Jeff Goldblum in a star-making performance that would see the character return again and again as the series continued.2 Sequels The Lost World (1997) and Jurassic Park III (2001) depicted a world where the consequences of unchecked scientific ambition begin to ripple outward — first threatening individual lives, then societies.

In these early entries, the central tension arose from questions of control. Can human beings contain what they create? Should they even try? Characters like John Hammond (Richard Attenborough) and Henry Wu (B. D. Wong) are cast as modern alchemists, eager to astonish the world with their creations while ignoring the moral weight of what they’ve done. Malcolm, of course, serves as a kind of prophetic voice, warning that nature — like truth — will not be domesticated.3

The Jurassic World trilogy, which began in 2015, traded some of that philosophical caution for blockbuster spectacle. The dinosaurs were bigger, the set pieces louder, and the themes a bit more diluted. These films — appropriately, perhaps — shifted the narrative toward commodification and commercialization, asking: What happens when awe is monetized and wonder repackaged as entertainment? Jurassic World imagined a functioning dinosaur theme park, complete with brand partnerships and genetic hybrids designed to boost ticket sales. The cautionary tale had evolved into a satire of late-stage capitalism, where even the monsters are marketed.4 Yet those familiar themes of the dangers of human pride, the extent of control, and the moral gray areas of scientific progress persisted through the trilogy, which brought back Malcolm as the prophet in the wilderness saying “I told you so” for its sophomore and final outings, Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom (2018) and Jurassic World Dominion (2022).

Which brings us to Jurassic World Rebirth. In many ways, the newest installment feels like a response — if not a corrective — to its immediate predecessors. Rebirth strips back the narrative from the “dinosaurs are loose in the world and we all must find a way to coexist” ending of Dominion to return the stakes to something a bit more intimate. Set five years after the conclusion of the last trilogy, the world has grown inhospitable to dinosaurs; only isolated equatorial enclaves remain habitable. Enter Zora Bennett (Scarlett Johansson), a covert ops specialist hired to lead a small, high-stakes expedition to a classified island research lab once part of the original Jurassic Park. Her mission is to retrieve genetic samples from the planet’s three largest remaining dinosaurs — creatures whose unique DNA holds potential life-saving properties for human medicine.

As Bennett’s team pushes toward the island, their path intersects with a family whose boat is damaged by prehistoric aquatic predators, stranding them together on the island. What they discover amid the jungle and crumbling labs is something far more sinister: genetically altered monstrosities — like the winged “Mutadons” and the highly-publicized six-limbed “Distortus Rex” (D-Rex) — products of long-abandoned genetic experiments that have quietly thrived on the island in the years since being abandoned.

What You Call Discovery… The titular park of the original film was an act of biological trespass, a violation of the created order in the name of progress. That theme has been a hallmark of the series and returns in Jurassic World Rebirth. Beginning with Jurassic World and the Indominus Rex — a lab-designed hybrid dinosaur created to impress shareholders — the series began to explore what it would look like if humans began manipulating dinosaurs, weaponizing them, bending them further away from what they were and toward what humans wanted them to be. The Indoraptor in Fallen Kingdom upped the ante as a creature bred not just for spectacle, but for militarization.5

Rebirth takes this idea to a logical and nightmarish conclusion. The island in question is less a forgotten outpost than it is a tomb for unnatural experiments. The new creatures that populate the third act of this film are genetic abominations, reminders that humanity, when unmoored from reverence for creation, will twist wonder into horror. Monsters, in a word, because they embody a particular kind of moral corruption: the result of innovation pursued without restraint, without conscience, or humility. In a way, Rebirth finally and fully realizes Ian Malcolm’s worst fears.6

In the original Jurassic Park, Malcolm warned that the geneticists were so preoccupied with whether they could, they never stopped to ask whether they should. In Rebirth, the “they” has changed, but the sin remains the same — only now it’s metastasized. The scientists we meet at the beginning of the film are responsible for creations that are not so much breakthroughs as they are betrayals of nature, giving rise to creatures shaped less by ecosystem or providence than they are boardroom directives and private funding. Here, the moral rot is not a flaw in the science — it is the very foundation of it.

From the beginning, it was never enough for Hammond’s InGen to bring the dinosaurs back. There was, Rebirth reveals, always something more — another gene to tweak, another asset to patent, another line to cross in the name of innovation. The illusion of progress masked a deeper impulse: to redefine extinct life according to human desire — and as the franchise has gone on, the more clearly it has shown that the real danger is not teeth and claws, but unchecked pride and rampant ambition.

The theological contours here are unmistakable. The Genesis account begins with a charge for humanity to steward creation as Yahweh’s representatives — not to own it, manipulate it, and certainly not to remake it after a broken image. The perverse science on display in Rebirth plays out like a parable drawn from Romans 1, wherein Paul extrapolates on the cost of worship shifting from the Creator to the creation, and humanity becomes futile in its thinking. What we see in the opening moments of Rebirth is not the forward march of life or the next stage of evolution, but a descent into the grotesque, into a world where creation has been desecrated and reassembled in man’s image. And that image, as always, is monstrous.7

Regardless of the film’s lukewarm reception among critics, Jurassic World Rebirth revives the moral questions that made the original film profound, but with a bit more of a cynical attitude. To the degree that it is a cultural reflection, there is a sobering idea here that was present even in the original film: that a civilization enamored with its own power will eventually lose sight of its limits. And that is an idea the Christian apologist can most certainly latch onto. Technological advancement is not the same as moral progress, and creation — once violated — tends not toward wonder, but toward ruin. What sets Rebirth apart is the warning that the cost of forgetting who we are is often deformation, not extinction. And that may be the more terrifying fate: to remain, but not as ourselves. To survive, but twisted beyond recognition.8

Paul in Romans speaks of those who exchange the truth of God for a lie and, in doing so, become futile in their thinking.9 Rebirth offers a shadow of that same truth, presenting grotesque mutations that are the result of vain thinking — progress divorced from purpose, and form without meaning. The monstrosities on screen reflect the shape of human ambition when it is empty and without substance, a moral collapse that is the image of man’s will unmoored from wisdom. When we sever creation from its Creator, we do not become gods — we become strangers to ourselves. And in Rebirth, the judgment is fitting: what was fashioned in man’s own image no longer obeys him.

Or, to put it in the words of Ian Malcolm: “God creates dinosaurs. God destroys dinosaurs. God creates man. Man destroys God. Man creates dinosaurs.”10 And now, with Rebirth, that statement could be amended to include, “Man creates something worse.”

Cole Burgett is a graduate of Dallas Theological Seminary and the Moody Bible Institute. He teaches classes in systematic theology and Bible exposition and writes extensively about theology and popular culture.

NOTES

- Read how Crichton conceptualized Jurassic Park here: Michael Crichton, “Jurassic Park: In His Own Words,” Michael Crichton, n.d., https://www.michaelcrichton.com/works/jurassic-park/.

- Malcolm’s status as the “voice of reason” and the “thematic mouthpiece” of the Jurassic Park franchise cannot be overstated. Philip Oltermann gives a helpful look at the character’s importance to the franchise here: Philip Oltermann, “The Star of Jurassic World Isn’t T-Rex. It’s Malcolm,” The Guardian, June 12, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/jun/12/jurassic-world-t-rex-malcolm-jeff-goldblum-dinosaurs-chaos-theory.

- For the uninitiated, “chaos theory” may be defined as “the study of apparently random or unpredictable behaviour in systems governed by deterministic laws.” Concepts like “the butterfly effect” arise from chaos theory, and the principles of chaos theory are used throughout the Jurassic Park franchise to underscore the idea that even with advanced technology and strict controls, complex systems — like an island full of resurrected dinosaurs — can quickly spiral out of control in unpredictable and catastrophic ways. See “chaos theory” in Encyclopedia Britannica, May 19, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/science/chaos-theory; also Christopher M. Danforth, “Chaos in an Atmosphere Hanging on a Wall,” Mathematics of Planet Earth, April 2013, http://mpe.dimacs.rutgers.edu/2013/03/17/chaos-in-an-atmosphere-hanging-on-a-wall/.

- Read about Jurassic World architect Colin Trevorrow’s approach to these themes when developing the story of the second trilogy of films here: Joe McGovern, “Colin Trevorrow on ‘Jurassic World’s Monster Star Indominus Rex,” Entertainment Weekly, May 25, 2015, https://ew.com/article/2015/05/25/meet-new/.

- Note well the thematic overlap between classic monster novels like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (which, by the way, carried the subtitle The Modern Prometheus upon publication in 1818) and the Jurassic Park films. This connection is articulated well by director J. A. Bayona when discussing his team’s creation of the Indoraptor from Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom. See Bill Desowitz, “‘Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom’: How J. A. Bayona and the VFX Team Channeled Classic Horror Movies,” IndieWire, June 25, 2018, https://www.indiewire.com/features/general/jurassic-world-fallen-kingdom-j-a-bayona-vfx-horror-1201978389/.

- For some insight into how the story of Jurassic World Rebirth came together, check out writer David Koepp’s comments in James Hibberd, “‘Jurassic World Rebirth’ Writer David Koepp on Making the New Movie Less, Well, Goofy,” The Hollywood Reporter, July 3, 2025, https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-features/jurassic-world-rebirth-david-koepp-interview-1236302775/.

- See Director Gareth Edwards’ comments on the creation of the D-Rex and the philosophy behind the creature’s monstrous appearance here: Ben Travis, “Meet the Distortus Rex: Jurassic World Rebirth’s Mutant Is ‘Like the T-Rex Designed by H. R. Giger,” Empire, May 2, 2025, https://www.empireonline.com/movies/news/jurassic-world-rebirth-distortus-rex-mutant-exclusive/.

- Interestingly, the working title of this film was Survival, and there was a layered meaning there that had to do with both the dinosaurs and the humans trying to survive the island with something intact. Make of that particular thematic current what you will. See Koepp’s comments during his interview with Hibberd in Hibberd, “Jurassic World Rebirth’ Writer David Koepp,” https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-features/jurassic-world-rebirth-david-koepp-interview-1236302775/.

- The word often rendered “futile” in Romans 1:21 is ματαιόω. It carries the connotation of being foolish or vain — empty and, in a sense, a shape without substance. Thoughts that are hollow, ultimately without form or grounding. It’s the same root behind the biblical idea of “vanity” in Ecclesiastes: a chasing after wind.

- Jurassic Park, directed by Steven Spielberg, screenplay by Michael Crichton and David Koepp (Universal Pictures, 1993).