Cultural Critique Column

Note: This is part of our ongoing Philosophers Series.

This article was published exclusively online in the Christian Research Journal, Volume 47, number 01 (2024).

When you support the Journal, you join the team and help provide the resources at equip.org that minister to people worldwide. These resources include our ever-growing database of over 2,000 articles, as well as our free Postmodern Realities podcast.

Another way you can support our online articles is by leaving us a tip. A tip is just a small amount, like $3, $5, or $10, which is the cost of a latte, lunch out, or coffee drink. To leave a tip, click here

There is a way that appears to be right,

but in the end it leads to death. (Proverbs 14:12)1Follow God’s example, therefore, as dearly loved children and walk in the way of love,

just as Christ loved us and gave himself up for us as a fragrant offering and sacrifice to God. (Ephesians 5:1–2)

What is the worth of an intellectual’s life? Is it a matter of influence in the academic world, the number of books published, one’s reputation among the elite in a discipline? Is it about popularity? Or is it more? How does one’s personal life — especially how a person treats others — factor into their value as a person and as an intellectual?

The British philosopher Derek Parfit was a major figure in contemporary philosophy until his recent death. The author of the influential work, Reasons and Persons (OUP, 1984), Parfit endeavored mightily to save the objectivity of ethics in a godless world. I referred to his work in the second edition of Christian Apologetics as a failure in this regard because his atheistic sense of the good could find no space in which to exist. I wrote:

One contemporary philosopher claims that objective morality exists, but God does not. In his massive, three-volume work, On What Matters [OUP, 2011], the eminent atheist philosopher Derek Parfit (1942–2017) tried to ground morality in something objective to avoid nihilism. He recognized the pull toward binding norms, but he thought he needed to square their existence with “the scientific worldview,” by which he means philosophical materialism. He also breezily rejects the ontological argument.

Parfit called this view Non-metaphysical Cognitivism (or Rationalism): “There are some claims that are irreducibly normative in the reason-involving sense, and are in the strongest sense true. But these truths have no ontological implications. For such claims to be true, these reason-involving properties need not exist either as natural properties in the spatio-temporal world, or in some non-spatio-temporal part of reality.”2

As one commentator put it, “This is about as far as one can go without metaphysics.” Parfit bars the existence of normative moral claims from “the spatio-temporal world” as well as from some “non-spatio-temporal part of the world” (the existence of which he denies). But there is nowhere else for them to go. For Parfit, there are moral claims that “are in the strongest sense true,” but which have no truth makers, no moral facts to which they correspond. These norms have “reason-involving properties,” but these properties have nowhere to attach themselves; they have no ontological domicile. They are ontological orphans. Worse yet, they could not even rise to the level of orphans, since orphans exist, although they are estranged. But Parfit’s norms are estranged from existence itself.3

Thus, I take Parfit’s meta-ethical attempt to ground morality (irreducibly normative claims) to be an utter ruin philosophically. Not only did he have no reason to attempt to construct a moral system without God, since there are so many good and sufficient reasons for Christian theism,4 his reasoning used to support that godless moral system is inadequate. There is no metaphysical space for the good to reside on his materialist account. Exit God; exit the good. Enter an impossible philosophy in service of the (nonexistent) good.5 Call it (a philosophical) mission impossible.

I offer this short critique in service of another related point. Because Parfit was an atheist, and because he developed his philosophy in a particular way, he was, therefore, a particular kind of person, a rather bad person. This is brought out with force in a recent review6 of a book by David Edmonds about Parson’s life and thought called, Parfit: A Philosopher and His Mission to Save Morality.7

Parfit was not as popular a philosopher as someone like Peter Singer, but he was influential in his academic sphere — a kind of philosopher’s philosopher. He was deemed so brilliant that he was offered an Oxford professorship without his having earned a doctorate. Paul Nedelisky’s review of Edmonds’s book begins with the account of Parfit shunning his once-lover and later friend, the American philosopher Susan Hurley, when she visited him in 2007. Although she was dying of cancer, Parfit refused dinner with her and even showed them to the door when they tried to visit his Oxford rooms because he was too busy working on his multivolume project On What Matters, despite having no deadline for the work. Nedelisky writes, “The Susan Hurley episode was not atypical for Parfit. His adult life was replete with instances of actively ignoring obligations to friends and family — and to many others besides — for the sake of his philosophical writing. As his partner of thirty years and eventual wife, Janet Radcliffe Richards, put it after his death, ‘I can’t think of anything we did together that wasn’t what he wanted to do.’”8

Parfit, according to Edmonds, made a wager that his philosophical work was so important that typical human relationships had to be spurned. In fact, “anything that took him away from this work must be studiously avoided. Hence, he ate the same food and wore the same clothes every day. He avoided social engagements and nonphilosophical conversation.”9 One might take this as mere hubris and grandiosity, but there is more — Parfit’s philosophy itself. Nedelisky summarizes Parfit’s influential book, Reasons and Persons: “Parfit seeks to undermine — among other things — the preeminence of special duties to those close to us, the rational basis for the fear of death, the existence of the soul, that each person is a separate individual, that people exist independently of social conventions, and that people deserve praise or blame for their actions.”10

Rather than addressing the arguments for these incredible views, consider how believing them would affect someone, particularly a philosopher who, instead of embracing nihilism, wanted somehow to preserve objective morality. Nedelisky explains Parfit’s philosophy. According to Parfit, traditional western morality is fundamentally wrong. “Put simply, the mistake is that this approach [to moral life] has been too personal — too concerned with duties to those who are close to us, too preoccupied with the distinctness of individual people, too hung up on people having souls that unite our experiences, too concerned with who deserves what. Instead, as Parfit sums up at the end of the book, ‘Our reasons for acting should become more impersonal.’”11

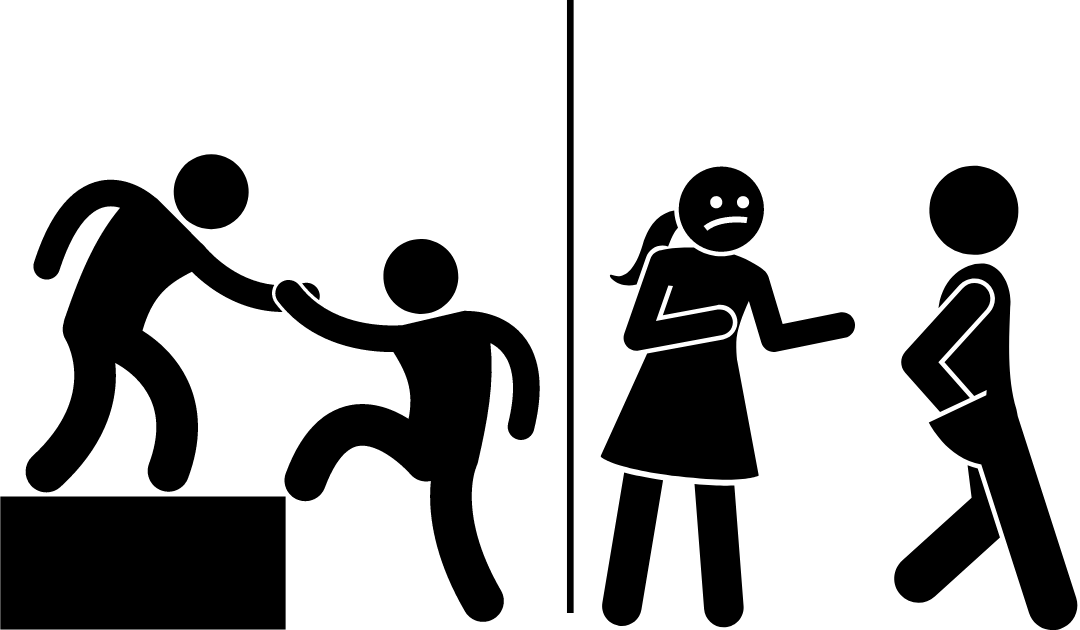

Nedelisky concludes his review of Edmonds’s book by linking the man with his philosophy. The more consistent Parfit was with his philosophy, the more impersonal his relationships became. Parfit’s biographer, Edmonds, commends him for this. One could take Parfit’s anti-social behavior as demonstrating a noble consistency between life and thought. Contrariwise, one could take it as a practical reductio ad absurdum of his philosophy given his lack of simple decency and compassion for his fellow human beings. Here is the argument:

- Any true moral system requires that common decency be given and shown to persons, all of whom are subjects of objective value.

- Any moral system that denies (1) is false.

- Parfit’s moral system denied (1).

- Therefore, (a) Parfit’s moral system is false.

- Therefore, (b) we need a better moral system to support (1). (I will give a brief case below that Christianity is that moral system.)

Contrast Is the Mother of Clarity: Parfit and Schaeffer. Parfit lived out his philosophy through his uncaring relationships with fellow human beings. He deemed his philosophical work to be of such importance that he could shun a former lover and “friend” who was dying of cancer. If my critique is correct, his work was not worth this uncaring spirit, since he lacked any metaphysical justification for objective goodness. His mission to save morality in an atheistic universe failed, despite his herculean efforts otherwise. And he became a worse person because of it.

The Christian is in another position entirely — regarding his worldview and sense of practical life with other human beings. The philosopher, apologist, evangelist, pastor, and activist Francis Schaeffer (1912–1984) provides a sharp contrast to Parfit, both in his worldview and in his relationships.

Schaeffer rightly argued that God’s character was the only sufficient foundation for objective morality, a view I defend at length in Christian Apologetics. His chapter, “The Moral Necessity,” makes this point in He Is There and He Is Not Silent, from which this quote is taken:

We can have real morals and moral absolutes, for now God is absolutely good, with the total exclusion of evil from God. God’s character is the moral absolute of the universe. Plato was entirely right when he held that unless you have absolutes, morals do not exist. Here is the complete answer to Plato’s dilemma; he spent his time trying to find a place to root his absolutes, but he was never able to do so because his gods were not enough. But here is the infinite-personal God, who has a character from which all evil is excluded, and so his character is the moral absolute of the universe. It is not that there is a moral absolute behind God that blinds man and God, because that which is farthest back is always finally God. Rather, it is God himself and his character which is the moral absolute of the universe.12 (Emphasis in original.)

Parfit attempts to affirm moral absolutes apart from God, a philosophy sometimes known as atheistic moral realism. I critique this idea at length elsewhere,13 but let it suffice to say that Christian theism provides a personal and perfect backbone to morality, based on the unchanging goodness of God, our Creator, who knows what is right for His creature. Moreover, the Christian ethic is one of deep concern for persons, divine and human. The greatest commandment, as Jesus taught, is to love God with all our being (since He is love [1 John 4:8] and He is our Lord) and to love our neighbors as ourselves (since they, too, are made in God’s image). Although Parfit was well-known for his book Reason and Persons, he could not associate reason with persons by grounding persons in divine love and their divine image. Schaeffer, on the contrary, offered a worldview that justified the existence of objective love and made it the leading priority of life. Both his worldview and his life-world were steeped in objective love for people.

Francis Schaeffer: Worldview and Way of Life. Biographer Colin Duriez notes that Schaeffer was known for his compassion for people.14 This concern shines through his writings. In the midst of an apologetic argument or philosophical distinction, Schaeffer often illustrates with a personal anecdote. The following two are moving. In the first, Schaeffer writes of our being made in God’s image and illustrates the significance with a story. “We…know something wonderful about man. Among other things, we know his origin and who he is — he is made in the image of God.”15 He then writes:

I was recently lecturing in Santa Barbara and was introduced to a boy who had been on drugs. He had a good-looking, sensitive face, long curly hair, sandals on his feet and was wearing blue jeans. He came to hear my lecture and said, “This is brand new, I’ve never heard anything like this.” So he was brought along again the next afternoon, and I greeted him. He looked me in the eyes and said, “Sir, that was a beautiful greeting. Why did you greet me like that?” I said, “Because I know who you are — I know you are made in the image of God.” We then had a tremendous conversation. We cannot deal with people like human beings, we cannot deal with them on the high level of true humanity, unless we really know their origin — who they are. God tells man who he is. God tells us that he created man in his image. So man is something wonderful.16

Notice how Schaeffer lovingly describes the young man’s features. He saw him as a unique person. Now consider that the warm greeting opened up a profitable apologetic conversation.17 Schaeffer’s worldview (to be technical, his theological anthropology), along with his moment-by-moment dependence on God, led to his loving engagement with this questioning young man.18

Another example illustrates Schaeffer’s method of “taking the roof off” of a non-Christian worldview by pressing the unbeliever to be consistent with his God-denying presuppositions. This exposes the falseness of the non-Christian worldview. The roof to be removed is the false sense of reality held by the non-Christian who has not discerned the illogic of his position.19 I will quote this anecdote in full in order not to lessen the ethos, pathos, or logos of this encounter.

I remember one night crossing the Mediterranean on the way from Lisbon to Genoa. It was a beautiful night. On board the boat I encountered a young man who was building radio stations in North Africa and Europe for a big American company. He was an atheist, and when he found out I was a pastor, he anticipated an evening’s entertainment, so he started in. But it did not go quite that way. Our conversation showed me that he understood the implications of his position and tried to be consistent concerning them. After about an hour I saw that he wanted to draw the discussion to a close, so I made one last point which I hoped he would never forget, not because I hated him, but because I cared for him as a fellow human being. He was accompanied by his lovely little Jewish wife. She was very beautiful and full of life, and it was easy to see, by the attention he paid her, that he really loved her.

Just as they were about to go to their cabin, in the romantic setting of the boat sailing across the Mediterranean and a beautiful full moon shining outside, I finally said to him, “When you take your wife into your arms at night, can you be sure she is there?”

I hated to do it to him, but I did it knowing that he was a man who would really understand the implications of the question and not forget. His eyes turned, like a fox caught in a trap, and he shouted at me, “No, I am not always sure she is there,” and walked into his cabin. I am sure I spoiled his last night on the Mediterranean, and I was sorry to do so. But I pray that as long as he lives he will never forget that when his system was placed against biblical Christianity, it could not stand, not on some abstract point, but at the point, but at the central point of his own humanity, in the reality of love.20

Schaeffer doesn’t tell us the man’s exact worldview or the arguments he used against it, but the unbeliever was likely an atheist who realized that his worldview could not justify common beliefs, such as the existence of other persons. Perhaps he was a nihilist. Nihilists can be easy game (simply produce something that they objectively value and you have refuted them), but Schaeffer repeatedly warned that apologetic encounters are not intellectual games to be won or lost. Notice he says, “I hated to do it to him.” Yes, we should have and give the best arguments, but we must love the person we are engaging with. The truth may injure them in their unbelief, but we should not add to that pain through arrogance or lack of concern. Schaeffer’s sensitivity to the reality of love as part of God’s objective reality led him to ask the final question of this dialogue. The man’s philosophy could not support the reality of his love for his wife. Christianity, as a metaphysical system, supports the reality of love, and, as a spiritual way of life, encourages living a life of love in the power of the Holy Spirit (1 Corinthians 13; Galatians 5:16–26).

Schaeffer expanded on this theme in The Mark of the Christian in his exposition of these two statements from Jesus:21

A new command I give you: Love one another. As I have loved you, so you must love one another. By this everyone will know that you are my disciples, if you love one another. (John 13:34–35)

My prayer is not for them alone. I pray also for those who will believe in me through their message, that all of them may be one, Father, just as you are in me and I am in you. May they also be in us so that the world may believe that you have sent me. (John 17:20–21)

Schaeffer’s exposition of these passages deserves a careful study, but suffice to note that our Christian love for other Christians and for non-Christians is (1) based on Jesus’ incomparable love for us demonstrated through His life and death; (2) commanded by Jesus; and (3) necessary evidence to unbelievers that the Father sent Jesus into the world for our salvation. Truly, to be a follower of Jesus is to live a life of love in the most radical way possible. That is the charge.

Intellect, Living, and the Grain of the Universe. There was a stark and sad contrast between Derek Parfit and Francis Schaeffer, both in worldview and in way of life. While Parfit was an intellectual of great distinction, his intellect was misused, given his atheism and doomed attempt to find objective morality apart from God. Some people, such as Parfit, use their intellectual gifts to cut against the grain of the universe instead of with the grain of the universe. And his life bore out his errant conclusions. Schaeffer had far fewer academic accolades than Parfit, but he knew “the God who is there,” as he put it. He thus knew the source of morality, the reality of love, and the meaning of persons as irreducible subjects of objective value and worth. And his life of love for people was borne out of his proper conclusions. May we follow Schaeffer’s lead in our worldview and in our loving ways of life.

Douglas Groothuis is Professor of Philosophy at Denver Seminary. Among his many books are Fire in the Streets: How You Can Confidently Respond to Incendiary Cultural Topics (Salem Books, 2022) and Christian Apologetics: A Comprehensive Case for Biblical Faith, Second ed. (IVP Academic, 2022).

NOTES

- Bible quotations taken from the NIV.

- Derek Parfit, On What Matters, vol. 2, ed. Samuel Scheffler (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 485.

- Douglas Groothuis, Christian Apologetics: A Comprehensive Case for Biblical Faith, second ed. (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2022), 355–56, Kindle ed. The original reference contains footnotes that document the quotations.

- For starters, see Groothuis, Christian Apologetics, and J. P. Moreland, Scaling the Secular City (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 1987).

- For a moral argument for the existence of God, see Groothuis, “The Moral Argument for God,” chap. 16, in Christian Apologetics.

- Paul Nedelisky, “Nothing Personal: How Ideas Made Derek Parfit,” Hedgehog Review, Fall 2023, https://hedgehogreview.com/issues/markets-and-the-good/articles/nothing-personal.

- David Edmonds, Parfit: A Philosopher and His Mission to Save Morality (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2023).

- Nedelisky, “Nothing Personal.”

- Nedelisky, “Nothing Personal.”

- Nedelisky, “Nothing Personal.”

- Nedelisky, “Nothing Personal.”

- Francis A. Schaeffer, He Is There and He Is Not Silent (1972; Carol Stream, IL: Tyndale House Publishers, 2001), 29, Kindle ed.

- See Groothuis, Christian Apologetics, chap. 16, and Douglas Groothuis and Andrew I. Shepardson, The Knowledge of God in the World and the Word: An Introduction to Classical Apologetics, chap. 6 (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2022).

- Colin Duriez, Francis Schaeffer: An Authentic Life (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2008).

- Francis A. Schaeffer, Escape from Reason: A Penetrating Analysis of Trends in Modern Thought (1968; Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 2006), 29, Kindle ed.

- Schaeffer, Escape from Reason, 29–30, Kindle ed.

- On the significance of greetings, see Douglas Groothuis “Learning to Say Hello Again,” Christianity Today, January 5, 2018, https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2018/january-web-only/learning-to-say-hello-again.html.

- On his sense of spiritual dependency on God, see Schaeffer’s classic, True Spirituality (Tyndale, 1972).

- See Francis A. Schaeffer, The God Who Is There (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2020), 156–58, Kindle ed.

- Schaeffer, The God Who Is There, 83, Kindle ed.

- Francis A. Schaeffer, The Mark of the Christian (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2006).