This article first appeared in the Christian Research Journal, volume 42, number 3/4 (2019). For further information or to subscribe to the Christian Research Journal please click here.

SYNOPSIS

Science fiction emerged in the aftermath of the Industrial Revolution; in recent years it’s been understood as a literature that focuses on the material world, one especially concerned with the effect of technological innovations on human life and social conditions. Some science fiction theorists and critics have turned that literary focus into a philosophical framework for interpreting these texts, conjecturing that stories so attuned to humanity’s material conditions must, on the one hand, stem from a disbelief in spiritual realities and, on the other, promote a naturalistic worldview and offer only political solutions to mankind’s ills. Darko Suvin exemplifies this tack, even going as far as to exclude from the science fiction canon any literary works that overtly take spirituality seriously. When it comes to American science fiction master Philip K. Dick, however, this automatic exclusion is difficult to enact. At the end of his career, it turns out, Dick wrote many stories that incorporated the mystical and gestured toward the theological. Rather than jettison Dick from the science fiction field, Suvin imposes a materialist hermeneutic that turns his spiritual plots into sociological parable. However, such readings diminish the original texts and put the interpretive cart before the literary horse. It offers unsatisfactory answers to questions about personhood and moral truth raised by Dick’s work, present even in stories like The Man Who Japed (Ace Books, 1956) that aren’t so blatantly transcendent but that nonetheless encourage readers to look beyond our material world for humanity’s ultimate truth and value.

Teaching in a small English program means I must be flexible in my course coverage. Over my sixteen-year tenure, I’ve taught classes on poetry, short fiction, contemporary literature, utopian fiction, introduction to literature, composition, literary theory, and more. Such an experience requires one to be nimble, especially when that range is stretched by disparate courses assigned within the same semester. That was my lot this past term, as I found myself teaching an ancient world literature course to beginning English majors alongside a science fiction class to graduate students. Within the span of a day, I’d have to swing from covering something like The Epic of Gilgamesh, written in 2100 BC, to H. G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds, published four thousand years later in 1898. Settling into this literary whiplash, I realized that the questions asked by these texts — written so far apart, and in such distinctly different forms — remained remarkably consistent.

SCIENCE FICTION AND GOODNESS, TRUTH, AND BEAUTY

It’s commonplace to consider the mythical stories of ancient world lit as concerned with elemental questions of human existence. Enuma Elish, Genesis, Theogony, Works and Days, The Iliad: these texts clearly sketch the parameters of the human condition, our origins, our nature, our ends, and help us better see (and appreciate) the beautiful, the good, and the true. Science fiction, on the other hand, has the opposite reputation. It’s associated with the here-and-now, the transitory, the merely material. Understandably so, given the centrality of technology and scientific developments to the genre. Science fiction’s focus on the machinery of life leads many writers, critics, and theorists to identify the whole field of science fiction as philosophically materialistic, as precluding any sincere allowance for the transcendent. In his distinction between fantasy and science fiction, author Ted Chiang captures this prevailing assumption: in fantasy, he says, the universe is understood as personal; in science fiction, impersonal.1

Like science itself, Chiang posits, science fiction works by observation, hypothesis, experimentation, and systematization — a detachment that bespeaks a mechanical worldview for Chiang and others like him who claim for the genre an ideological bent instead of distinguishing it primarily by its formal qualities. For groundbreaking science fiction scholar Darko Suvin, a materialistic worldview is essential to science fiction. Any work that takes spirituality seriously, then, is by definition disqualified. Such is the case Suvin makes against calling Walter Miller’s A Canticle for Leibowitz (Lippincott, 1960) science fiction.2 Rather than treating religion merely as cultural material, a sociological phenomenon at the mercy of historical processes, as Suvin would prefer, in this one-of-a-kind post-apocalyptic Cold War novel, Miller makes space for and even promotes faith; for that, Suvin excludes the story from the science fiction canon.

Questions of genre sometimes seem tedious to those outside the literary discipline. What does it matter, one might ask, if Suvin identifies Miller’s novel as fantasy, not science fiction? In the case of A Canticle for Leibowitz, probably not much. Despite being grounded in time and space, Miller’s story is infused with enchantment, an enchantment impossible for readers to ignore no matter the generic label provided. With its relics and rituals, saints and icons, legends and miracles, Canticle offers a supernatural irruption into the presumably closed system of history. In other cases, though, the philosophical strictures of Suvin’s definition can easily obscure the intricacies of the text itself and unfairly skew the resulting interpretations. Rather than illuminate the material under consideration, a faulty generic framework can blunt for readers a text’s creative force.

Amid Change, What Remains

Take, for example, the work of famed science fiction author Philip K. Dick. While Miller intermingles the staples of science fiction — nuclear fallout, technological advancement, scientific discovery — with the traditions of the church, Dick is much more of a science fiction purist, populating his worlds with androids, rockets, and aliens. His characters experience alternate histories, time travel, chemical mood enhancement, dystopian regimes, and virtual realities. In this way, Dick’s writing does precisely what Suvin describes as the logic of science fiction: “organiz[ing] variable spatiotemporal, biological, social, and other characteristics and constellations into specific fictional worlds and figures.”3 But, with all due respect to Suvin’s considerable contributions to science fiction studies, such a literary orientation to the variables of human existence does not necessarily entail or promote a naturalistic mindset. Science fiction may be what Sheryl Vint calls “the literature of change,”4 but paradoxically that constant change can point us more insistently to what about the human condition and human beings themselves that stubbornly remains the same. Concerns with the corporeal, in other words, need not be at the expense of belief in the spiritual and, in fact, have purchase only if undergirded by “something more.” As the work of Dick encourages us to consider, attentiveness to the material conditions of human existence can — and I think should — awaken us to ultimate truths and values.

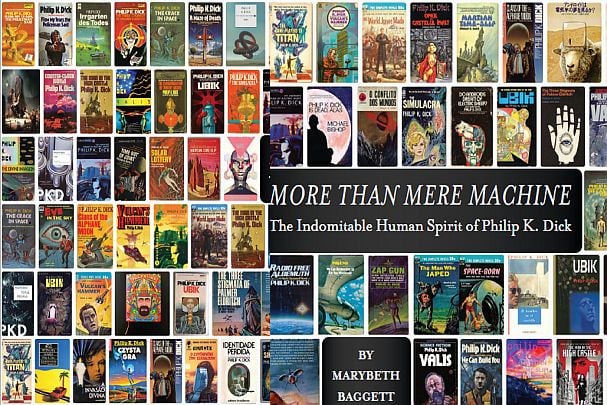

Born in 1928, Philip K. Dick lived a troubled life from the outset. His twin sister Jane died little more than a month after birth, and this tragedy haunted his writing over the course of his career, surfacing in his fiction as a consistent leitmotif.5 Dick came of age in Berkeley, California, shaped by both his parents’ tumultuous marriage and the radical politics of that hotbed of the mid-century American countercultural movement. These circumstances simultaneously sharpened and challenged Dick’s precocious spirit, and out of that crucible emerged a body of work almost unparalleled among science fiction writers in quantity and quality. The author of over forty novels, Dick also wrote short stories galore, publishing more than ten collections; together these works changed the face of science fiction. Perhaps more significantly, he amassed this large oeuvre before dying prematurely at sixty-three after a life-long bout with poor physical and mental health, a destructive drug habit, and a string of failed marriages.6

Philip K. Dick pushed the previously sacrosanct boundaries of science fiction and, while drawing on the common tropes of science fiction, often subverted them and opened up new possibilities for these highly imaginative stories. In doing so, he challenged readers’ expectations, created zany worlds for his characters to inhabit, and coined new words that hint at the technological innovations defining his fictional worlds. Even accounting for Dick’s tremendous output, the number of his books now deemed science fiction classics is remarkable. Suvin identifies six as such,7 including The Man in the High Castle (Putnam, 1962),8 The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch (Doubleday, 1965),9 and Dr. Bloodmoney, or How We Got Along After the Bomb (Ace Books, 1965).10 In Suvin’s assessment, the best of Dick’s books have centered on questions of society as the ground of and force behind all human relationships, particularly the role of the Marxist concepts of alienation11 and reification12 and the possibilities of social renewal through radical politics.13

READING PHILIP K. DICK AS A MATERIALIST

Suvin is certainly on to something. Dick’s work, following the general trend of science fiction, explores the implications of social and technological change.14 To be sure, the modern era that spawned science fiction was replete with scientific discoveries, technical innovation, and industrial encroachment. Promise and peril accompanied such rapid, ubiquitous social change, and as Suvin notes, Dick’s novels imaginatively consider both extremes. The Man in the High Castle, for example, depicts the “politico-ethical conflict between murderous Nazi fanaticism and Japanese tolerance,” ultimately judging Japanese rule the better option.15 For Suvin, any consideration of values, truths, or moral realities within Dick’s texts must be circumscribed by historical processes and material conditions. Thus, all of Suvin’s interpretations reduce to consideration of power relations: Dr. Bloodmoney envisions the collapse of preexisting power structures and the possibilities of a utopian communal order;16 Martian Time-Slip (Ballantine, 1964) entangles an insignificant everyman in a nightmarish web of destructive capitalistic practices;17 and The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch tells the tale of an “interplanetary industrialist who peddles dope to enslave the masses.”18

Even though Dick’s later novels delve into theological and cosmological territory,19 Suvin still prefers interpretations that transpose those concerns to a “highly abstract or coded form of transitive talking about individual vs. community and other crucial matters of relationships among people in Dick’s time.”20 In other words, theological material is merely symbolic of historical processes, what Suvin calls “a parable of collective earthly matters.”21 Coloring Suvin’s reading of any given Dick novel, then, is his assumption that “in the collective, non-individualist world of Dick, everybody, high and low, destroyer and sufferer, is in an existential situation which largely determines his/her actions.”22 For Suvin, Dick’s worlds are thoroughly materialistic. Nevertheless, there is arguably much about Dick’s work that resists such a reading, and only distortion of the text itself can force it into a materialist mold. Many insights Dick offers about personhood and agency, for example, are an uneasy fit in a naturalistic universe, most especially his insistence on the need for moral responsibility in an increasingly technocratic world.

SATIRE AS MORAL GUIDE

In Dick’s The Man Who Japed (Ace Books, 1956), for example, the protagonist Allen Purcell embarks on an urgent search through which he learns that being fully human in an ever-more-automated world requires him to actively discover meaning and to appropriate it for himself. It demands that he rebel against the status quo, which offers only ready-made, easy-to-digest, one-dimensional answers to life’s most pressing questions. Rather than succumb to the situation at hand and be constituted by it, as Suvin argues Dick’s characters inevitably do, Purcell assesses his situation, finds it morally wanting, and undertakes to change it. Even if this undertaking ultimately falls short, the story affirms Purcell’s moral judgment, which challenges Suvin’s materialistic reading of Dick’s work. Rather than find their locus in historical processes, the values Purcell embraces and champions, and that readers affirm through their emotional support of Purcell’s actions, go beyond his political and social environment. I’m not suggesting that Dick himself is intentionally promoting a theistic worldview in his novels; rather, his works raise crucial questions that a materialistic view can answer, if at all, only with considerable difficulty.

Morec Society, the world of The Man Who Japed, is regimented and controlled, with oppressive restrictions on the citizenry’s reading and behavior; in it, too, the constant threat of exposure and punishment for even the smallest offense keeps people in line. As the book opens, Purcell is a pillar of his community: from his perch at Allen Purcell, Inc., he creates moral propaganda reinforcing societal norms. Purcell’s initial break comes in his “japing” — or vandalizing — of a statue of Major Streiter, Morec’s founder. His fear of detection along with his serendipitous meeting of Gretchen Malparto, a woman deeply dissatisfied with Morec norms, forces him to face the inconsistencies and injustice of his totalitarian world.

While Purcell has learned to adapt to his stifling, stultifying environment, he finds many aspects of it reprehensible, among them the block meetings that allow anonymous accusers to humiliate their neighbors publicly; technology also disconnects people from each other, and constant surveillance threatens to expose every indiscretion. In spite of his society’s overtly stated principles of valuing its citizens, its so-called morality is self-righteous, voyeuristic, detached, pious, uncaring, and uncompassionate. Gretchen explains this poor fit between Purcell and the society he operates in: “Yes, your ethics are very high. But they’re not the ethics of this society. The block meetings — you loathe them. The faceless accusers. The juveniles — the busybody prying. This senseless struggle for leases. The anxiety. The tension and strain….And the overtones of guilt and suspicion.”23 There must be some objective, transcendent standard that reveals that society as corrupt.

Purcell is also a misfit in his role as propagandist. For example, a propaganda “packet” he created is rejected by Sue Frost, a high-ranking Committee Secretary, because it is not clearly in line with Morec principles. Its meaning is not as obvious as it should be for its readers readily to grasp its message. His employee, Luddy, explains the concern: “It’s not a moral question, Al. It’s a question of clarity. The Morec of that packet doesn’t come across.”24 He finds that Morec society has no allowance for personal conscience, something Purcell highly prizes. Morality is thus sacrificed at the altar of clarity, convention, and compliance.

Fear is the weapon of choice wielded to reinforce this dualistic thinking. The citizens of Morec had witnessed a nuclear holocaust and cling to Morec principles as the only means of preventing a recurrence. A minor character explaining the statue vandalization exemplifies this twisted thinking: “The people that did this mean to overthrow Morec. They won’t rest until every scrap of morality and decency has been trampled into the ground. They want to see fornication and neon signs and dope come back. They want to see waste and rapacity rule sovereign, and vainglorious man writhe in the sinkpit of his own greed” (emphasis in original).25 The prevailing belief system rests on this binary opposition, one that when interrogated falls apart: citizens are offered either Morec or depravity. Purcell, on the other hand, recognizes that Morec is depravity.

But, because Purcell is so entrenched in the system, Gretchen must clarify his position to him: “You’re not a ‘mutant’; you’re just a balanced human being….The japery, everything you’ve done. You’re just trying to re-establish a balance in an unbalanced world.”26 Rejecting the dualistic thinking of Morec — the historically contingent, politically complicit distortion of actual truth and goodness — allows Purcell to discover and more fully embrace enduring values, and with them his essential self. While David Mackey interprets this move as Purcell “breaking out from being a passive receiver of Morec’s reality structure and becoming the active shaper of his own reality,”27 what better explains the situation is Purcell apprehending a misfit between his society’s rules and nonnegotiable deliverances of authentic moral truth, and through an act of will embracing the better vision. This righteous rebellion takes place through Purcell’s production and broadcasting of a satire on Morec society patterned on Jonathan Swift’s “Modest Proposal.”

AN INVETERATE HUMAN QUALITY

As the allusion to Swift reminds us, satire depends on the notion of a shared morality. As the Literary Reference Center explains, satire is “intended to expose and ridicule vice, corruption, folly, short-sightedness, pretense, hypocrisy, and bias,” aimed at communal good; it can thrive only where “there is a clear difference between expected moral behavior and duty and actual behavior.”28 If Morec — the historical situation — determined moral values, then Purcell’s satire would not be able to find its mark, as it so clearly does. And readers recognize in other Dick stories the valor of moral underdogs who also buck against an unjust system, a pattern that recurs in Dick’s novels, according to Dennis Weiss and Justin Nicholas.29 Although Dick’s heroes don’t fit the Hollywood uber-masculine stereotype, they nonetheless “quietly refus[e] to bow to the pressures of a society and a technology that attempt to flatten and control his existence.”30 Figures such as Nobusuke Tagomi and Frank Frink in The Man in the High Castle, John Isidore in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (Doubleday, 1968), and Douglas Quail in the short story “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale” populate the Dickian corpus; in their stubborn resistance to authoritarianism, these characters illustrate the quintessence for Dick of a significant part of what it means to be human: an innate resistance to oppression and a tenacious insistence on an objective and universal standard of moral goodness that outlasts transient earthly powers. “This, to me, is the ultimately heroic trait of ordinary people; they say no to the tyrant and they calmly take the consequences of this resistance….In essence, they cannot be compelled to be what they are not.”31

Dick’s work is marked by this inveterate human quality, whose obstinacy is matched by its authenticity. In Dick’s extrapolative stories, spun by introducing to the plot what Suvin calls the novum,32 whatever human impulses and experiences emerge intact, unchanged by the contingent factors at play, just might point to essential truth. Contra Suvin, the more variables in the mix, all the more fundamental and revelatory is what remains. That is, in fact, what I’ve discovered from my semester immersed in literary texts that span humankind’s written record. Wells and Dick, no less than Hesiod or Homer, reveal to us who we are, help us understand the weighty moral challenges we face, and emphasize the sustaining values and virtues that necessarily transcend any given cultural moment, try as some might to domesticate, deflate, or deny them.

Marybeth Baggett is professor of English at Liberty University and serves as associate editor for MoralApologetics.com. She holds a PhD in Literature and Criticism from Indiana University of Pennsylvania, and — along with her husband — has recently published The Morals of the Story: Good News about a Good God with IVP Academic.

NOTES

- Justin Lee, “The Elitism of Fantasy vs. The Egalitarianism of Science Fiction: On Ted Chiang’s Impersonal Universe,” ArcDigital, October 14, 2018, https://tinyurl.com/yaxj27h4.

- Darko Suvin, Metamorphoses of Science Fiction (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1979), 27.

- Suvin, Metamorphoses of Science Fiction,

- Sherryl Vint, A Guide for the Perplexed: Science Fiction (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014), 135–158, http://dx.doi.org.

- John Wilson, and Ray Mescallado, “Philip K. Dick,” Magill’s Survey of American Literature, revised edition, September 2006, 1–10, https://www.ebscohost.com.

- Wilson and Mescallado, “Philip K. Dick.”

- Darko Suvin, “P. K. Dick’s Opus: Artifice as Refuge and World View,” Science Fiction Studies 2, 1 (1975): 8–22, https://www.ebscohost.com.

- The Man in the High Castle describes an alternate history wherein the Axis Powers defeated the Allieds in WWII.

- The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch is a dystopian novel of space colonization, blending cyborg technology with religious iconography.

- Bloodmoney tells a postapocalyptical tale of nuclear holocaust survivors rebuilding society in the aftermath of the fallout.

- Christian Metz, “Alienation,” The Encyclopedia of Literary and Cultural Theory (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011). On Marxist terms, alienation refers both to the way human labor is converted into objects that belong to the owners of the means of production and to the experience of living under capitalism, which relies on such a process.

- Metz, “Reification,” The Encyclopedia of Literary and Cultural Theory. With the term reification, Marxist critics point to the capitalistic process of quantifying human labor as a means to study and manipulate it.

- Suvin, “P. K. Dick’s Opus,” 21.

- Sherryl Vint, A Guide for the Perplexed: Science Fiction (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014), 135, http://dx.doi.org.

- Suvin, “P. K. Dick’s Opus,” 10.

- Suvin, “P. K. Dick’s Opus,” 11.

- Suvin, “P. K. Dick’s Opus,” 14.

- Suvin, “P. K. Dick’s Opus,” 14.

- In 1974, Dick experienced what he interpreted as a mystical epiphany, which influenced much of his later work.

- Darko Suvin, “Goodbye and Hello: Differentiating within the Later P. K. Dick,” Extrapolation 43, 4 (2002): 370, https://www.proquest.com.

- Suvin, “Goodbye and Hello, 375.

- Suvin, “P. K. Dick’s Opus,” 9.

- Philip K. Dick, The Man Who Japed (New York: Vintage, 2002), 120.

- Dick, The Man Who Japed, 15.

- Dick, The Man Who Japed, 133.

- Dick, The Man Who Japed, 119.

- Douglas A. Mackey, Philip K. Dick (Boston: Twayne, 1988), 26.

- “Satire,” EBSCO Literary Glossary, 2019, ebscohost.com.

- Dennis Weiss and Justin Nicholas, “Dick Doesn’t Do Heroes,” Philip K. Dick and Philosophy, ed. D. E. Wittkower (Chicago: Open Court, 2011), 37.

- Weiss and Nicholas, “Dick Doesn’t Do Heroes,” 37.

- Philip K. Dick, “How to Build a Universe That Doesn’t Fall Apart Two Days Later,” The Shifting Realities of Philip K. Dick: Selected Literary and Philosophical Writings, ed. Lawrence Sutin (New York: Vintage, 1996), 279.

- Suvin, Metamorphoses, 10. This novum, or “new thing,” distinguishes science fiction stories from other genres and makes possible their speculative nature, setting up imaginative thought experiments that present reader and writer alike with questions of “what if?”