This article first appeared in the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL, volume 39, number 06 (2016). The full text of this article in PDF format can be obtained by clicking here. For further information or to subscribe to the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL go to: http://www.equip.org/christian-research-journal/

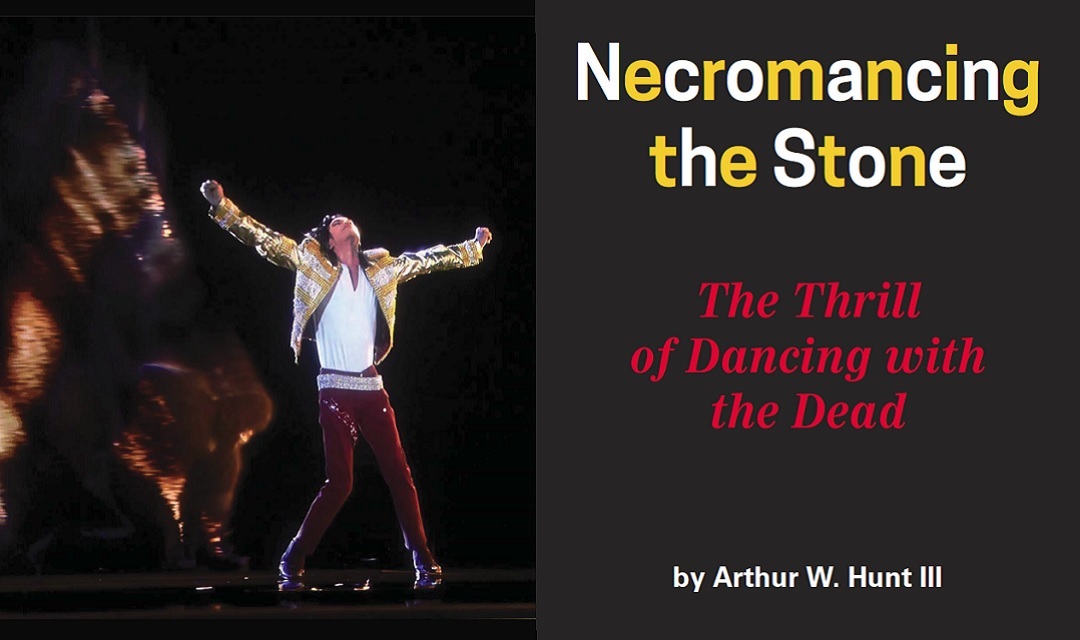

“Michael Jackson came back to life,” said USA Today in reference to a Billboard Music Award telecast in 2014. Pulse Evolution, the company that pulled off the techno thriller, used the same technique several years ago to “summon the ghost of slain rapper Tupac Shakur” at the Coachella music festival.1

The necromantic language seems appropriate. These are not music videos per se, but live performances. Since Jackson had been dead for six years, the Billboard event carried the ambiance of a séance — only with pizazz. During the concert, Jackson’s image skipped across the stage in sync with real dancers as he sang “Slave to the Rhythm,” from his posthumous album, Xscape. Future concerts plan to feature Elvis Presley, Frank Sinatra, and Marilyn Monroe.

Whether Ghost Dancing (my term) will become a new entertainment venue or just another passing fad remains to be seen, but it says something about the progression of celebrity culture born more than a century ago out of the Graphic Revolution.

Celebrity and the Graphic Revolution

In his groundbreaking book The Image, historian Daniel Boorstin described how our culture had created “a thicket of unreality which stands between us and the facts of life.”2 Taken together, telegraphy, photography, radio, cinema, and television brought forth the pseudo-event, an occurrence staged to call attention to itself.

Boorstin was not just concerned with the now-familiar “photo-op” or “media event.” He put his finger on a much larger problem. Americans not only confused the copy with the original but also actually preferred the copy to the original. News was no longer gathered; it was made. The traveler, a person who travails, had been replaced with the tourist — a person who stays at American hotels in France made to look like French hotels.

The hero, a person known for his achievement, had been replaced with the celebrity — a person known only for his wellknownness. The celebrity’s claim to fame is fame itself; she is a person notorious for her notoriety. The movie star’s success came to overshadow the person they actually portrayed. Thus, one might say, Charlton Heston overshadowed Moses; John Wayne upstaged Davy Crockett; and Leonardo DiCaprio is better known than Howard Hughes.

As early as mid-nineteenth century, astute observers were anticipating the consequences of the Graphic Revolution. Before the Civil War, a young Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote in The Atlantic Monthly that the advent of photography would separate form from reality. He said the “image would become more important than the object itself, and would in fact make the object disposable.”3

Holmes believed the whole affair would be akin to a hunter poaching beasts in the field: “Every conceivable object of Nature and Art will soon scale off its surface for us. Men will hunt all curious, beautiful, grand objects, as they hunt cattle in South America, for their skins and leave the carcasses as of little worth.”4

Later, Christopher Lasch described the twentiethcentury modern as a person caught in a house of mirrors. He wrote in The Culture of Narcissism, “We live in a swirl of images and echoes that arrest experience and play it back in slow motion. Cameras and recording machines not only transcribe experience but alter its quality, giving to much of modern life the character of an enormous echo chamber, a hall of mirrors.”5 Were Lasch alive today, what would he say about Facebook and YouTube?

The interesting thing about the Graphic Revolution is that one technology did not replace the other — radio did not replace television — rather, each innovation built on the last one as each converged with the other. While communications technologies have become more portable and de-massified, they have not diminished the pseudo-event or stopped manufacturing celebrities.

In some ways, the navel gazing that goes on in social media has made us all stars within the cyber-universe. Celebrities are, after all, dream wishes about ourselves. As Dolly Parton once told Reader’s Digest, “People don’t come to see me be me, they come to see me be them.”6

What do Jackson, Elvis, Monroe, and Sinatra have in common? None of them committed heroic deeds. Nevertheless, each contributed substantially to modern show business. Before World War II, the singer was subordinate to the orchestra in billing and score. But when Columbia Records released Sinatra’s “All or Nothing at All” during the Christmas of 1943, the subordination flipped, and the young crooner became an object for which young girls wept and screamed.

This was just the beginning of the screaming. Ed Sullivan knew what Elvis did with his hips, and refused to let him on his show for precisely this reason. But when Steve Allen’s ratings shot through the roof with Elvis’s appearance, Sullivan would not be outdone. He booked the singer for three shows and paid him $50,000.

Elvis brought rock and roll out of the closet, defined the genre, and became its icon. Today we think of Elvis’s gyrations as rather tame, yet there is little doubt they paved the way for the stylistic crotch grab. Jackson, unarguably a talented artist, extended the cult of celebrity for solo performers and transformed the music video industry.

Pagan Beauty

We would be mistaken to think celebrity power of this magnitude began with Sinatra, Monroe, Elvis, or Jackson. The first celebrity that wielded this much attention was Egypt’s pharaoh. In addition to being a despot and a god, the pharaoh was a celebrated person. Historian Will Durant writes that it took an entourage of twenty people just to manage his toilet. There were barbers to cut his hair, manicurists to paint his nails, hairdressers to adjust his royal cowl, perfumers to deodorize his armpits, and makeup artists to blacken his eyelids and redden his cheeks.7

Art historian Camille Paglia says Egypt gave us the first Beautiful People. Somewhere between the pyramids and the Nile, the notion of vogue was born. Paglia says in Sexual Personae, “Egypt invented glamour, beauty as power and power as beauty….Hierarchy and eroticism were fused in Egypt, making a pagan unity the west has never thrown off.”8

Paglia’s newest book, Glittering Images: A Journey through Art from Egypt to Star Wars, continues these audacious insights.9 She is the only pagan I know of who gets it right when it comes to paganism. Taking her cue from Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy, Paglia traces the development of pagan beauty in art from Egypt to Mount Olympus where the Greeks and Romans cast their gods in their own image and then began to emulate them. Zeus and Bacchus were large, exaggerated personalities — Big People — who did great feats and then went down into the village to drink and rape.

But this is an oversimplification. The pagan personae is much more complicated. As I explain in my book The Vanishing Word, art was not just the vehicle whereby the Greeks worshiped themselves but also the way they understood and made their culture.10 The Greeks improved on those universal forms found in Egyptian kouros. As Paglia says, “The Greek kouros, inheriting Egypt’s cold Apollonian eye, created the great western fusion of sex, power, and personality.”11

The Athenian cult of beauty found its supreme theme in Apollo — the beautiful boy — cool, distant, and in total control of his environment. His image begins in Egypt, runs through Athens, Rome, and into the Italian Renaissance. We find him in European romanticism and then into the mass idolatries of today’s popular culture. Paglia describes him as beardless, sleek, dreamy, remote, autistic, and lost in a world of androgynous self-contemplation. He is the classic Greek male with a high brow, strong straight nose, fleshy cheeks, full petulant mouth, and short upper lip. He is Apollo, Blue Boy, Lord Byron, and Elvis Presley.12

The restrained Apollonian ideal stands in tension with its chaotic Dionysian antipode. The god of wine and revelry also played an important part of Greek society, as reflected in cult festivals given over to sexual display and ugly brutality. Sometime during the period of the emperors, the Dionysian dynamic became more prevalent in Roman culture. When Nero held mock marriages with men, sometimes playing the groom and sometimes the bride, he was making an artistic statement.

The pendulum between Apollonian restraint and Dionysian revelry swings back and forth in Western culture. In doing so, the beautiful boy becomes grotesque. Artistic forms are so turbulent in popular culture today that we actually can see the pendulum swing in the life of a single artist (e.g., Disney’s Bubblegum Queen Britney Spears devolving into a sadomasochist freak woman).

Michael Jackson began his career as the boy wonder of the Jackson 5. His showmanship was more compelling than anything Donny Osmond could give us. After Jackson broke with his brothers, he established himself as the performer par excellence — youthful, dynamic, and agile. Even as an adult man, Jackson was still a squeaky-voiced youth. He was Peter Pan, the boy who never wanted to grow up. Over time, cosmetic surgeries, public embarrassments, and drug abuse shriveled Jackson’s personae into that of an oddity. Like Elvis and Monroe, he died when aging would have jeopardized his sculpted image.

Dancing with the Dead

Pulse concerts use a sophisticated twist on an old magician’s trick. Employing a technique called Pepper’s Ghost, computer wizards cast the entertainer’s image onto a sheet of glass tilted at a 45-degree angle aided by high-powered digital projectors. Live performers are added to the mix, creating an illusion the star is right there in the room.

John Henry Pepper amazed audiences in 1863 when he used the trick in a scene from Dickens’s The Haunted Man. Since that time, Pepper’s Ghost has been used in the Haunted Mansion and Phantom Manor at Disney’s theme parks and at the 2006 Grammy Awards, when Madonna used the technique in a live performance. Only recently have concert producers employed the trick to summon the dearly departed.

Thus far, no deceased performer has appeared in a full-length concert, but that doesn’t mean it won’t happen. If the history of technology teaches us anything, it is that if it can be done, then by all means, it should be done. To enjoy Jackson moonwalking across the stage postmortem requires some suspension of the imagination — something to which you have to open yourself up.

Ian Drew, entertainment director at US Weekly, who witnessed the Jackson concert, told USA Today that people would not come to one of these performances to see the sophistication of the technology; rather, they would come for the communal experience.13

Does this border on necromancy? Technically, these performances do not qualify as necromancy in the old sense of the word. However, few would deny the feat is several steps removed from watching Disney’s Hall of Presidents. The communal aspect of the event is dubious at best, and there is a certain audacity about inserting flesh-and-blood performers into the memory of a celebrity king such as Jackson.

Paglia again in Personae: “[This] is not the Age of Anxiety but the Age of Hollywood. The pagan cult of personality has reawakened and dominates all art, all thought. It is morally empty but ritually profound.…Movie screen and television are its sacred precincts.”14

Jackson’s projected image was no more a real ghost than the one I saw several years ago at a local college’s rendition of Hamlet. Our real dance with the dead is to be found in the shadows of a pagan past, those images once chipped in stone that just keep coming back.

Arthur W. Hunt III (arthurwhunt.com) is an active member of the Media Ecology Association, founded by Neil Postman. He is the author of The Vanishing Word: The Veneration of Visual Imagery in the Postmodern World (Wipf and Stock, 2003/2013) and Surviving Technopolis: Essays on Finding Balance in our New Man-Made Environments (Pickwick, 2013).

NOTES

- Marco della Cava, “A Techno Thriller,” USA Today, May 23, 2014, 1A.

- Daniel Boorstin, The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America (New York: Vintage Books, 1961), 3.

- Oliver Wendell Holmes, “The Stereoscope and the Stereograph,” Atlantic Monthly, June 1859, reprinted in Photography Essays and Images, ed. Beaumont Newhall (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1980), 53–54, in Stuart Ewen, All Consuming Images: The Politics of Style in Contemporary Culture (New York: Basic Books, 1988), 25.

- Holmes, “The Stereoscope and the Stereograph,” in Ewen, All Consuming Images, 25.

- Christopher Lasch, The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations (New York: Warner Books, 1979), 96–97.

- “Quotable Quotes,” Reader’s Digest, June 2001, 73.

- Will Durant, Our Oriental Heritage (New York: MJF Books, 1992), 163.

- Camille Paglia, Sexual Personae: Art and Decadence from Nefertiti to Emily Dickinson (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1990), 59.

- See Camille Paglia, Glittering Images: A Journey through Art from Egypt to Star Wars (New York: Pantheon, 2012).

- See Arthur W. Hunt III, The Vanishing Word: The Veneration of Visual Imagery in the Postmodern World (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Books, 2003).

- Paglia, Sexual Personae, 112.

- Ibid., 115, 121.

- Marco della Cava, “Singer’s Mirage Heralds Future,” USA Today, May 23, 2014, 8A.

- Paglia, Sexual Personae, 32.