This article first appeared in the Christian Research Journal, volume 41, number 2 (2018). For more information about the Christian Research Journal, click here.

SYNOPSIS

Evangelical Christians often have two major problems with the ancient creeds. First, we object to the use of creeds on the grounds that those documents convert biblical language into philosophical categories, in contrast to our insistence on using the Bible’s own language. This objection fails to recognize that the creeds sought “to collect the sense of the Scriptures” and that only rarely did they use philosophical language.

Second, we are ambivalent toward the ancient creeds because they seem to be very incomplete summaries of what we believe — in particular, they are silent about justification by faith. This objection fails to recognize that the creeds do cover justification by faith, but in a different way than the way we describe it. Both of these objections grow out of a misunderstanding of the nature and purpose of creeds. They were not meant as summaries of what we believe, and they did not originate in theological controversy, even though they were shaped by such controversy to some degree. Instead, they grew out of the biblical depiction of Christian identity based on the one in whom we believe, to whom we belong, by whose name we are called, and they were used initially for public professions of faith in connection with baptism. Properly understood, creeds give us the opportunity to join Christians from throughout history in publicly pledging our allegiance to Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

During the first several centuries of Christian history, believers expressed their faith through short statements called “creeds” (from the Latin word credo, meaning “I believe”).1 There were many such statements, but two of them, the Apostles’ Creed and the Nicene Creed, became the most universally accepted extrabiblical statements in the Christian church. As a result, one might think that evangelical Christians would have a great appreciation for the creeds, and some do. But many evangelicals today are only vaguely aware of the creeds, or we have a big problem with them. I suggest that there are two major reasons for our ambivalence about the ancient creeds: we believe we should have no creed but the Bible, and we think the ancient creeds don’t summarize what we believe very well anyway. In this article, I would like to explain and respond directly to both of these problems that we have with the creeds. But more important, I would like to suggest that our ambivalence is based on a misunderstanding of what the creeds are and how they were meant to function. Understood properly, the creeds can and should be a vital part of the way we express our Christian faith, as they have been vital to most Christians throughout history.

OUR FIRST PROBLEM: NO CREED BUT THE BIBLE

Evangelicals are ambivalent toward the creeds because they contain language that doesn’t come from the Bible. Many of us proudly and correctly affirm our allegiance to Scripture alone as the ultimate authority for our faith. Why then should we use any language other than the Bible’s own words to describe that faith? Creeds come from outside the Bible, and they are other people’s articulations of our faith. Why do we want to dredge up dusty language from the distant past, rather than speaking of Jesus ourselves, in our own way? And the language of the creeds is not only unbiblical and other people’s language but also philosophical. We sometimes argue that in the creeds, Greek philosophical categories such as ousia (“essence”), hypostasis (“person” or “subsistence”), and energeia (“energy” or “activity”) distort the Christian faith by transforming it into static metaphysics. Why should we mar the gospel by speaking of Christ with philosophical categories rather than biblical ones?

Stating the problem this way highlights two major features of Western (especially American) Protestant Christianity: biblicism and individualism. “I have no creed but the Bible,” we often say. We have elevated to iconic status the rugged individual who questions extrabiblical authority wherever he or she finds it. Our romantic model is the frontier woman or man reading the Bible alone — one person reading only one book — grasping its truth and speaking of Jesus using the words of Scripture. With such a model before us, what need do we have of creeds?

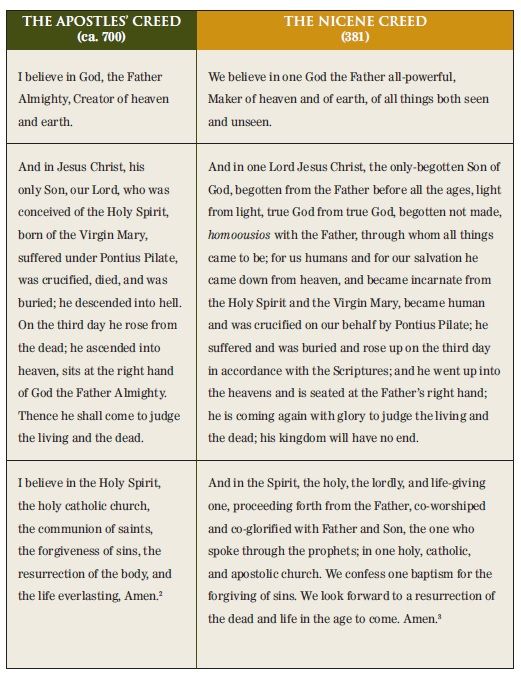

If this is our reason for rejecting the creeds, then we are in for a bit of a surprise when we actually read them. The following table contains English translations of the Apostles’ Creed (written in Latin) and the Nicene Creed (written in Greek):

Virtually everything in these two creeds is taken directly or almost directly from Scripture. A few phrases in the Nicene Creed sound funny to us, such as “begotten from the Father before all the ages.” But this is not philosophical language. It is an attempt to make sense of the fact that Jesus is God’s Son (which means He is somehow derived from God), and yet He is eternal (hence, “before all the ages”). In fact, the only philosophical word in either creed is homoousios, which means “consubstantial,” or “one in being.” It stresses that in whatever way the Father is God, the Son is God in the same way. If the Father is all-holy, all-loving, and all-powerful, so is the Son. In fact, the great fourth-century Egyptian theologian Athanasius, as he explained why the framers of the creed used the strange word homoousios, famously wrote that they sought “to collect the sense of the Scriptures, and to re-say and re-write what they had said before.”4

The creeds were not meant to convert biblical language into philosophical language. Nor were they meant to replace scriptural language or usurp biblical authority. Instead, they were meant as summaries of biblical teaching, whose very language was condensed from the Bible’s own language as much as possible. It is true that Christian theology often is expressed in philosophical categories, but when we criticize the creeds for being overly philosophical, we are making them guilty by association with our theological language. Their language is actually far simpler than we seem to realize.

OUR SECOND PROBLEM: THE CREEDS DON’T SUMMARIZE OUR FAITH WELL

We think the creeds do a rather poor job — or at least a rather incomplete job — of summarizing what we believe. We are told that the creeds emerged in the midst of theological controversy (this is partly true), and that they were designed to articulate what we believe in opposition to the heresies of the day. But in the minds of many evangelicals, the biggest heresy is works righteousness, and thus the most central Christian affirmation is justification by faith. There is seemingly no mention of justification by faith in the Apostles’ Creed or Nicene Creed. What use do we have for creeds that omit a doctrine so central to the Christian faith?

To address this problem, we need to recognize that part of the point of “justification by faith” is to remind us that we are not the objects of our own faith. We depend for salvation not on what we do but on what Another has done. We should recognize that this is what the creeds are saying, too, but in a different way. By telling the story of Jesus and by naming the Father, Son, and Spirit as the actors in that history, the creeds are specifically omitting our own action or performance. This omission is just as significant as the inclusion of what Jesus did. By that very omission and inclusion, the creeds call us to look elsewhere besides ourselves — to the Father, Son, and Spirit — for our salvation. The very act of telling the story of Jesus (as the Gospels do, as the New Testament preachers do in the book of Acts, and as the preachers and creed writers of the early church do) is just as much an affirmation of justification by faith as we make when we — following Paul in Romans and Galatians — actually expound on that phrase itself. If evangelical readers can remain attuned to what the creeds don’t say as much as to what they do say, we may find some of our suspicions allayed.

In addition, the Nicene Creed does more than “cover” justification by faith merely by omission of human action. It also covers this distinctive positively through a phrase that comes at the very center of the creed. After describing who the Son is eternally in relation to the Father, the creed transitions to what the Son has done — the events of His life, death, and resurrection. This transition marks the center of the creed, and the language used there is striking: “For us humans and for our salvation he came down from heaven.” In contrast to other religions, Christianity insists that human beings cannot work our way up to God; God has to come down to us. And the Nicene Creed gives pride of place to the central assertion that God the Son had to come down, and did come down, to save us.

THE PROBLEM WITH OUR PROBLEMS

Behind both of these problems, I believe, lies a deeper misunderstanding of what the creeds actually were and how they functioned. We think the creeds were designed to declare what we believe in contrast to significant distortions or heresies. In fact, those of us who recite the creeds in our churches usually preface them with the question, “Christians, what do you believe?” But this is not the question the creeds were answering. If you are surprised by that assertion, let’s step back from the creeds to the Christian faith as a whole for a moment.

At the very heart of the Christian faith lies not an ethical system (as important as that is), nor a set of commandments (although there are many of those), nor even a set of doctrines (although they too are very important), but a name. Peter tells the Jewish leaders, “There is no other name under heaven given among men by which we must be saved” (Acts 4:12).5 Following Jesus’ command, new Christians are baptized “in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit” (Matt. 28:19). Indeed, by calling ourselves “Christians,” we are naming ourselves after Christ, our Lord. The most important thing about us is not what we do, or even what we believe per se, but to whom we belong, as shown by the one whose name we bear.

Furthermore, the one to whom we belong is also the one in whom we believe. Paul writes to the Romans, “If you confess with your mouth that Jesus is Lord and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved” (Rom. 10:9). This simple statement includes a fact that we believe — that God raised Jesus from the dead — but even more fundamental is its confession of who this Jesus whom God raised from the dead was. He was and is the Lord. Therefore, at the most basic level, being Christian involves confessing who Jesus Christ is in relation to God, affirming that we belong to Him because we bear His name, and believing the fundamental truths of His history — His incarnation, life, death, resurrection, and ascension. What we do grows out of what we confess, which grows out of the one to whom we belong and in whom we believe — the one by whose name we are called.

If we think about Christian identity in this way, we can see that the ancient creeds were not meant as comprehensive declarations of what we believe. They are more like pledges of allegiance to the one in whom we believe, the one to whom we belong and by whose name we are called. In fact, the creeds did not actually originate in theological controversies, although such controversies did shape some of the language they used. More fundamentally, the creeds grew out of biblical precedents adapted by the early church for use in baptismal liturgies. Let’s look at this development.

CREEDLIKE PRECEDENTS IN SCRIPTURE

It is persuasively argued that the initial source of all Christian creeds was Deuteronomy 6:4. The Lord says through Moses, “Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God, the Lord is one.” This is not actually a creed, but it functioned as a creed by focusing on Israel’s allegiance to the one undivided God in whom they believed and to whom they belonged. In New Testament times, the church made the same affirmation. As Paul eloquently puts it in 1 Corinthians 8:5–6, “For although there may be so-called gods in heaven or on earth — as indeed there are many ‘gods’ and many ‘lords’ — yet for us there is one God, the Father, from whom are all things and for whom we exist.” The most basic affirmation of ancient Israel has become — in a context at once very different and yet fundamentally similar — the most basic affirmation of the church as well. We pledge allegiance to the one true God.

Of course, there was also another stunning truth — seemingly in conflict with the first — that had to be learned and wrestled with. The rest of 1 Corinthians 8:6 reads, “And one Lord, Jesus Christ, through whom are all things and through whom we exist.” Notice the striking parallels between the way the one God, the Father, is described and the way the Lord Jesus Christ is depicted. The Father is the one from whom everything exists and for whom we exist; Jesus Christ is the one through whom we and all other things exist.

Along with confessing the identity of Jesus with God, the New Testament writers also affirm creedlike summaries of the saving events of Christ’s life. Paul describes the gospel in 1 Corinthians 15:3–4 as follows: “For I delivered to you as of first importance what I also received, that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the Scriptures.” We see that the New Testament writers complicate the creedal affirmation of faith in one God by affirming with equally creedal force that Jesus Christ is to be identified with that one God, and by attaching particular creedlike significance to the events of Christ’s life, death, and resurrection. There is a hard line between God and everything else, but Christians affirm that Jesus belongs above that line, and yet lived an earthly life as one below it.

There is yet another complication in the nascent creedal affirmations of the New Testament. Some of them confess not only God/Father and Jesus/Lord but also a third person. Paul concludes 2 Corinthians with the famous benediction (13:14), “The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ and the love of God and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit be with you all.” And of course, we have already seen that in Matthew 28:19, Jesus commands Christians to baptize “in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit.” While the Holy Spirit receives far less attention in the New Testament than Jesus does, the creedlike affirmations in these and other passages indicate that He too belongs above the hard line dividing God from all created things.

CREED WRITING IN THE EARLY CHURCH

The creedal impulse latent in the New Testament documents continued into the second and third centuries. Several different types of creeds were produced, but the type that came to predominate was three-fold, with a section on each of the three Trinitarian Persons. Following the pattern of Matthew 28:19, these three-fold creeds were used in baptism, as the candidate would confess faith in the persons sequentially and be immersed after each confession. The candidate would be asked, “Do you believe in God the Father?…Do you believe in Jesus Christ his only Son our Lord?…Do you believe in the Holy Spirit?” Over time, these interrogatory creeds were rewritten as declarative creeds, with a sentence or paragraph for each of the persons. Thus, the baptismal use of creeds — growing out of the Lord’s command — came to dictate the pattern that future creeds would follow.

From this sketch, it should be clear that the roots of the creeds lay deep in biblical and Christian history. They did not emerge merely as a result of theological controversy, even though such controversy did lead to expansions of their content to ward off heresies. As a result, we can see that the purpose of creeds was never to give a comprehensive outline of the “what” of salvation, and thus the omissions of key doctrines that disturb us should not do so. Instead, creeds served as pledges of allegiance by which new converts and worshipers affirmed their loyalty to God, to His Son, and to His Spirit. The content of creeds was designed primarily to indicate the persons to whom the worshipers were pledging their allegiance.

Why then should Christians committed to the Bible alone as ultimate authority care about the ancient creeds of the faith? We have seen that these creeds were not meant to replace the Bible or to be authoritative in their own right but “to collect the sense of the Scriptures.” We have seen that they did not leave out the great truth of justification by faith but handled it in a different way than we do. Most important, we have seen that they were not actually meant as summaries of what we believe, and thus should not be judged to be inadequate as doctrinal statements. Instead, the creeds were meant as communal pledges of allegiance to Father, Son, and Spirit. The Apostles’ Creed has been used for over a millennium by virtually all Western Christian groups, and the Nicene Creed has been used for over a millennium and a half by all Christian groups, Western or Eastern, Orthodox, Catholic, or Protestant. These creeds give us the opportunity to join with the entire Christian church throughout history in confessing our faith.

Christians, in whom do you believe? “We believe in one God, the Father…and in one Lord Jesus Christ, the only-begotten Son of God…and in the Spirit, the holy, the lordly and life-giving one.” Amen.

Donald Fairbairn is the Robert E. Cooley Professor of Early Christianity at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary and the Academic Dean of the Charlotte campus. He is the author, coauthor, or cotranslator of eight books, including the forthcoming The Story of Creeds and Confessions, from which this article is adapted.

NOTES

- This article is adapted from Donald Fairbairn and Ryan Reeves, The Story of Creeds and Confessions (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, forthcoming). Used by permission of Baker Publishing Group.

- Jaroslav Pelikan and Valerie Hotchkiss, eds., Creeds and Confessions of Faith in the Christian Tradition, vol. 1 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003), 669.

- Pelikan/Hotchkiss, Creeds and Confessions, vol. 1, 163 [modified by restoring the key term to Greek].

- Athanasius, Defense of the Nicene Definition, chap. 20; in Nicene- and Post-Nicene Fathers, second series, vol. 4, 163-4.

- All scripture quotations are from the ESV.