Cultural Apologetics Column

This article was published exclusively online in the Christian Research Journal, Volume 46, number 04 (2023).

This is an feature length Viewpoint online article.

When you support the Journal, you join the team and help provide the resources at equip.org that minister to people worldwide. These resources include our ever-growing database of over 2,000 articles, as well as our free Postmodern Realities podcast.

Another way you can support our online articles is by leaving us a tip. A tip is just a small amount, like $3, $5, or $10, which is the cost of a latte, lunch out, or coffee drink. To leave a tip, click here

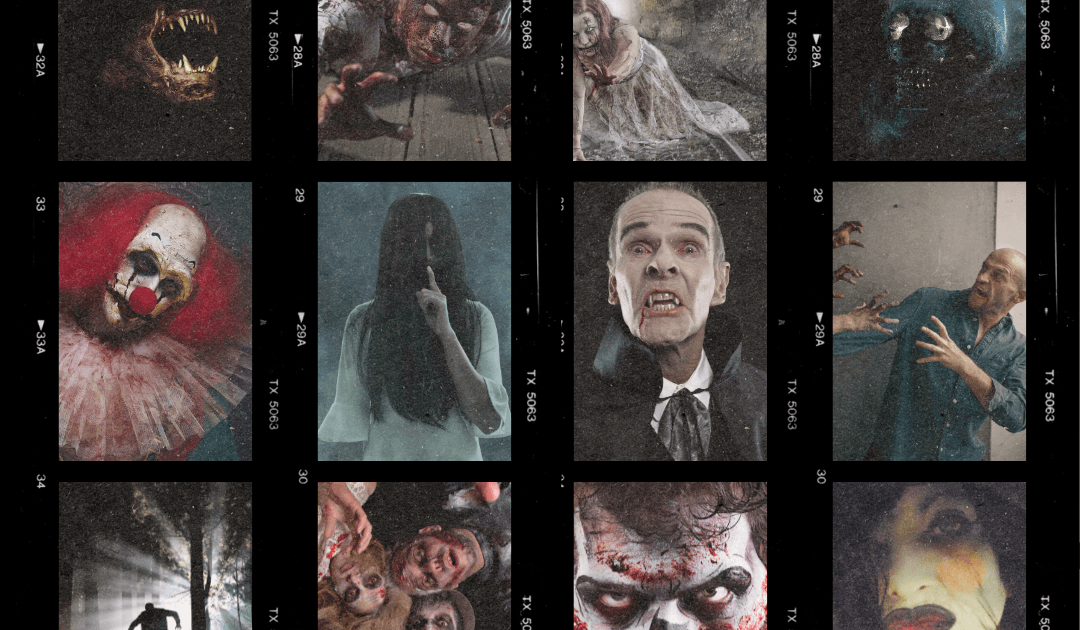

Few genres in cinema draw as visceral a reaction as horror. Often igniting fiery debates concerning the genre’s moral implications, many find the grim tales and nightmarish scenes that typify horror films too disconcerting to stomach. While undeniable that the genre has seen more than its share of poorly conceived films that prioritize shock over substance, to dismiss horror entirely is to overlook the stark morality that underpins many of its best entries.

When executed with skill and intention, horror films underscore a fundamental tenet of existence: evil is real, and it must be dealt with. With this as a foundation, the best entries of the horror genre become less a sensationalist endeavor, and more a profound exploration of the darkest corners of morality.

Early Horror Cinema. While the roots of the horror genre reach far back into history, perhaps the most logical starting point for “horror cinema” among modern audiences would be the classic monster films produced by Universal Studios from the 1920s through the 1950s. This is where the popular image of so many “classic monsters” that claws its way to the surface of the public conscience every October can be traced. As pop culture historian Michael Mallory notes, “While some of these characters preexisted in mythology or literature, the iconic forms, images, and identities that we immediately recognize in them today all emanated from one place: Universal Studios.”1

These are the movies that captured my imagination as a child. While most of my friends were preoccupied with the much-maligned “slasher” flicks, I was content to stalk the corridors of dark, gothic castles with the likes of Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff. Those “classic horror” films, though black-and-white, held something that many of the then-modern horror movies did not. What I did not (or perhaps could not) recognize at the time is that that those old-school horror films maintained a very clear morality. Lugosi’s Dracula, a character that has been deconstructed and reinterpreted a hundred times over, is downright evil. There is none of the “sexy vampire” nonsense in the 1931 Dracula. The Count’s seductiveness, his ability to hypnotize, to sway the mind, is unsettling, as it should be.

Yet the heroic Van Helsing, portrayed by Edward Van Sloan, is shown to be fearless when faced by Dracula, simply because he is not taken in, mentally or emotionally, by evil. To this day, I get chills every time I watch the scene wherein Dracula attempts to hypnotize Van Helsing, only to fail. He then lunges to kill, only for Van Helsing to coolly and simplistically produce a crucifix that rebuffs the Count’s advance. The feeble old man who, in many other horror films, would be the first character to be offed, does not give one inch of ground in that scene. Instead, he is rooted by his convictions and an absolute unflinching resolve in the face of evil. Reviewing the film upon its release in 1931, Mordaunt Hall, writing for the New York Times, reported of the scene, “there was a general outburst of applause when Dr. Van Helsing produced a little cross that caused the dreaded Dracula to fling his cloak over his head and make himself scarce.”2 Forget Captain America — we should all want to be Van Helsing when we grow up.

Beyond bringing the classic characters of gothic literature, like Dracula and Frankenstein, into the twentieth century, Universal Studios was also responsible for adding a wealth of iconic characters to the horror film pedigree. After hearing Nazi propogandist Joseph Goebbels deliver an anti-Semitic tirade, German writer Curt Siodmak emigrated to England and later the United States, where he penned perhaps the most mythic of Universal’s monster films, The Wolf Man (1941).3 Drawing upon his experiences in Germany, Siodmak crafted a tragedy about the difficult relationship between an overbearing father and his soft-spoken son, the power of suggestion, and one good Samaritan’s doomed attempts to escape a dark fate foisted upon him. In the process, Siodmak codified multiple “tropes” that are now commonplace in the modern horror lexicon, including pentagrams, silver bullets, and transformations by night. Siodmak’s original screenplay for the film, titled Destiny, was a major inspiration for my own werewolf tale, the award-winning audio drama series, The Lost Son.4

In the 1950s, as sci-fi flicks like The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) and The War of the Worlds (1953) captured the public conscience, Universal released The Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954). Set in the Amazon, where a team of geologists uncover a fossil that they believe is a “missing link” between land and sea animals, the film introduced the famous “Gill-man” monster. Filmed in three dimensions with scenes shot underwater, the movie was a technological marvel for its time, paving the way for many “creature features” in years to come. Independent filmmakers Sam Borowski and Matt Crick released a documentary in 2015 commemorating the film’s 60th anniversary. Reflecting on the film’s cultural footprint, Borowski said:

I’m a huge fan of Gill-Man, who I think is one of the most influential movie characters of all-time. If not for a Creature from the Black Lagoon, would we even have an Alien or a Predator? How many creatures have taken their look from the original Gill-Man? What about movies such as Jaws that emulate other elements [of the original Creature film] such as music and cinematography? Creature from the Black Lagoon just might be the most imitated movie of all time, and our project shows why.5

But perhaps none of the Universal monsters have left as deep an imprint on the cultural psyche as Boris Karloff’s moving portrayal of Frankenstein’s monster in Frankenstein (directed by James Whale, 1931). “He is the undisputed king of Universal’s classic monsters, a towering, brutal, but often child-like creature who was built and imbued with life by Dr. Henry Frankenstein, and kept alive by his children and their successors.”6 The image of Frankenstein’s monster with a flattop and metallic protrusions on either side of the neck endures, bearing little resemblance to how Mary Shelley originally envisioned the character because of legendary makeup artist Jack Pierce’s iconic design, which took three-and-a-half hours to apply to Karloff, and nearly two hours to take off.

Karloff’s version of the monster is horrific because of his naivety — a clear moral center requiring the viewer to understand innocence as a good thing, and to be horrified when that innocence is shattered. Looking back on Karloff’s career, film critic Terrence Rafferty concluded that his “lurching, baffled newborn monster in ‘Frankenstein’ is a beautiful and imaginative piece of work, a perfectly economical little poem on the perils of poor impulse control.”7

When discussing horror films, it is nigh impossible to overstate the significance of Universal Studios during the genre’s fledgling years. The popular images of the classic monsters that have endured in the public imagination for generations can be traced to these films, which by modern viewing standards are largely bloodless and void of much sex appeal. Perhaps that is why these characters persevere, despite the endless parodies and reimaginings that seek to complicate the simple morality that drove these early films.

A Shift in Tone. By the time of the early ’60s, the classic monster stories were given a makeover by British film production company Hammer Film Productions Ltd. For the next decade, the likes of Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee rose to prominence for their reinterpretations of the iconic movie monsters. The most important of these reinterpretations, and perhaps the most important for shaping the cultural image of the vampire going forward, was Lee’s take on Dracula. As noted by Australian film professor John Potts, “Lee redefined Dracula as suave, aristocratic, sensual; his Dracula is the face of Hammer horror. These were the films I saw at the Saturday matinees in the early ’70s.”8

Meanwhile, American horror cinema was reinventing itself. Alfred Hitchcock released Psycho in 1960, and in 1968 independent horror filmmaker George A. Romero released Night of the Living Dead, effectively codifying the tropes of the “zombie” feature. But the metamorphosis would not be complete until 1974 with the release of Tobe Hooper’s disturbing The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. Iconic film critic Roger Ebert described the feature as “a real Grand Guignol of a movie. It’s also without any apparent purpose, unless the creation of disgust and fright is a purpose. And yet in its own way, the movie is some kind of weird, off-the-wall achievement.”9

Within four years, John Carpenter would release Halloween (1978), bringing the subgenre known as the “slasher film” to the fore of horror cinema. While these early entries were (in hindsight) relatively tame and even, one can argue, skillfully made, the subgenre’s reliance on blood and gore would come to define the horror market for the remainder of the twentieth century and into the early part of the twenty-first. The subgenre’s ongoing prominence as the “face” of the horror genre is undeniable. Film critic Josh Bell notes, “As a whole generation grew up watching slasher movies at sleepovers and summer camps, the genre itself became a major influence on future horror filmmaking….At this point, slasher movies are firmly established as a cornerstone of horror, beyond simple trends.”10

While the slasher subgenre remains as dominant a force as ever, the first quarter of the twenty-first century has, understandably, produced horror films that hew closely to the social issues plaguing a more globalized culture. Popular works such as The Purge (2013) and its franchise envision a horrific dystopian future where a single night of murder per year is deemed socially acceptable. Others, like Joran Peele’s Academy Award-winning Get Out (2017), address racial issues. In Britain, several low-budget horror films have helped launch the careers of many popular actors, from 28 Days Later (2002), featuring Cillian Murphy, to Eden Lake (2008), starring Michael Fassbender, and Attack the Block (2011), which featured John Boyega and Jodie Whittaker. And this is to say nothing of the numerous Chinese, Japanese, and Korean horror films that have received widespread critical acclaim. The horror film genre remains alive and well a century on, transcending cultures and demonstrating its malleability and wide-ranging appeal.

What Has Been Lost. Yet for all their popularity, many horror films of the past fifty years have lost something important. Ebert’s analysis of Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre as being “without any apparent purpose” is indicative of the shift in filmmaking philosophy that began occurring back in the ’70s. This has been the topic of numerous discussions with one of my professional collaborators, Canadian horror filmmaker Manuel H. Da Silva, who once remarked to me, “Nobody seems to want to make horror movies with a message anymore.”11

Da Silva, as a filmmaker, is poking at the same thing that Ebert, the film critic, has analyzed, and what I will try to put a fine point on by characterizing as an erosion of that very basic morality that was inherent in the genre’s earliest entries. To say that “They don’t make ’em like they used to,” with regard to horror films, is to suggest that many of the popular horror films today exist to scare (if it aspires to anything at all) or to “gross out” its audience, and little else.

Famed horror author Stephen King, in his seminal essay on the topic, argues that “mythic” (an important choice of word) horror films serve the purpose of “keep[ing] the gators fed” by “deliberately [appealing] to all that is worst in us. It is morbidity unchained, our most base instincts let free, our nastiest fantasies realized.”12 From a humanistic perspective, King’s argument makes some degree of sense. The horror film taps into a primal kind of bloodlust, the likes of which has not really been seen outside of the ancient Roman Colosseum and select contact sports like traditional pugilism and, more recently, mixed martial arts.

Yet there is a world of difference between Connor McGregor and Victor Frankenstein. And, I would argue, that “keeping the gators fed” is likely a secondary concern to someone like James Whale, one of Hollywood’s earliest openly gay film directors, whose 1935 horror film The Bride of Frankenstein has consistently been hailed as a masterpiece and one of the greatest horror films ever made.13 “Other than humor, Whale contributed little to the modern slasher film,” reflects Lloyd Rose, former theater critic for the Washington Post. She continues:

He saw some very ugly action, including Passchendaele and the Battle of the Somme, before ending up in a POW camp, where he began his stage career by producing amateur theatricals….A slasher movie at least takes the body seriously by acknowledging how awful its mutilation is. That awfulness is the source of the horror. But by aestheticizing deformity, Whale actually hits the audience harder than any gross, realistic portrayal would….In his own way, in a condescended-to genre, Whale made genuine, angry art out of the war that, if it didn’t actually kill his lover, bloodily destroyed much of his generation.14

For Whale, one of the preeminent creators of horror films in the last century, the genre was about more than satisfying any kind of age-old bloodlust. He had personally witnessed enough bloodletting to “keep the gators fed” for several lifetimes; instead, the horror film was a way of processing his own trauma. The “German Expressionism” style that has now become a hallmark of the genre can even be traced to Whale. Rose notes:

Whale had seen the great German silent horror movies that were never widely released in this country, and from them…[he] created the style of Universal Studios Gothic…hollow, cold-seeming places in which the actors seemed somehow fragile and out of place, at fate’s mercy. The mix of beauty, perversity, wit and fear in Whale’s monster pictures is the goal that every horror director worth his salt has aspired to since.15

Rose’s analysis of Whale’s work reveals his influence in the films of Alfred Hitchcock, Orson Welles, Gordon Willis, and Brian De Palma, demonstrating the difference in DNA between “good” horror films and those that have come to dominate the landscape in the last fifty years. This is not to say that there is nothing to commend those early entries of the slasher subgenre — which, again, is the preeminent subgenre of horror film today and the “image” of the horror movie most readily conjured in the minds of popular audiences. As a filmmaker myself, I appreciate the tightness of the camerawork and the economic use of very contained sets in Carpenter’s original Halloween, for example. That being said, however, the series quickly lost credibility when it became about inventing new and interesting “kills,” moving Michael Myers from his status as simply “the Shape,” an indefinable force born from childhood trauma, to a ridiculous and credulity-stretching killing machine. Many audiences stopped watching at that point — and rightly so! Turning off a horror film is a completely acceptable ending to the movie.

But a horror film created with any sense of intentionality, one created with a “purpose,” to use Ebert’s expression, or “with a message,” to use Da Silva’s idea, is one that takes evil seriously enough to recognize that, on this side of eternity, it is inescapable. Rose picks up on this as the very essence of the Universal Studios monster films’ visual style, one which frames the characters, even the heroes like Van Helsing, even the tragic figures like Larry Talbot, as being “at fate’s mercy.” These are films less concerned about a body count and ratcheting up the gore factor than they are about what has gone awry in the human soul, and how even the best intentions, when carried out thoughtlessly, can be twisted and perverted by evil. More than this, these are films that understand evil is real, and that is something no one can afford to ignore.

The Christian Response? Of all the people in the world today, Christians have no business being naïve. It therefore interests and perplexes me immensely that, of all the genres of film out there, the one that Christians have so readily handed over to the culture is horror. I enjoy a good testosterone-fueled action-adventure barnburner as much as the next guy, but I can also readily admit that none of the films featuring John McClane, John Wick, and Jason Bourne have the same level of philosophical and mythological — even theological — depth as, say, Whale’s Frankenstein duology. And those two movies are certainly void of any of the horrid sentimentality that saturates the vast number of “family friendly” Hallmark films that play on television screens in so many Christian households across the nation.

Having said that, the unfortunate reality that must be acknowledged is that much of the zeitgeist has come to be dominated by horror films that exploit rather than examine — and there is a difference. Even Scripture employs what might today be seen as “horror tropes,” such as the strange séance carried out by the witch of Endor, as recorded in 1 Samuel 28, or the frightening appearance of the Gadarene demoniac in the synoptic Gospels.16 But Scripture does not put the emphasis on the horrific for the sake of horror — that is as shallow as the sentimentality that trades on emotion for the sake of emotion. The way in which the horrific is handled, the tone and attitude toward the material, makes the difference. It must be horror “with a message,” or horror “with a purpose.”

And, it turns out, when handled in such a way, horror can actually be an extremely effective genre of storytelling. As Christian writer Mark Eckel points out regarding the Gothic novels on which many of those classic Universal monster films were based, “Gothic horror stories are morality plays. Human nature is best understood when we consider why Dr. Moreau thought he could remake animals in his image. We understand our true nature when we identify with the decaying portrait of Dorian Gray. And we begin to realize the tension between our dignity and depravity when reading about Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.” He concludes, “There is nothing scary about Gothic horror literature, except to know the horror is in me,” which is a remarkably biblical assertion (see Romans 1–3)!17

Long have I maintained that horror is perhaps the one genre easiest for a Christian, especially one interested in cultural apologetics, to take hold of. And this for the simple reason that it remains the one genre that begins with the assumption that evil is real and must be dealt with. But the best the genre has to offer does not keep the horror external, as is the case with many slasher flicks. Instead, the best entries hold up a mirror to us, exposing us to what is, in essence, our sinful natures, frequently run amuck and left unchecked.

As I often tell my students, lacking a well-rounded understanding of sin, its pervasiveness, and the crisis of humanity’s condition, inevitably leads to one lacking a well-rounded understanding of the gospel. If the crux of cultural apologetics is examining artifacts produced by a culture and using those artifacts as a springboard into conversations about the gospel, then the best horror films function as a natural and somewhat obvious on-ramp to those discussions.

None of this is to say, of course, that there is no such thing as a bad horror film. They are plenty and, arguably, the majority. Yet tossing the genre as a whole is to rob the culture of one of the few artifacts that still maintains a fundamental belief in an evil that cannot be medicated or therapied into remission. Never once does Van Helsing suggest simply sitting Dracula down and educating him on how to be a more socially acceptable vampire. Or, even better, he does not try to convince audiences that vampirism is “sexy” or “desirable” or simply one oddball Count’s method of “self-expression.” The solution is to drive a stake through his heart, plain and simple. In a similar way, Paul does not suggest that the “old man” can be therapied into a right standing before the Father; no, he must be crucified with Christ, that the body of sin might be done away with (Rom. 6:6).

The best horror films take evil seriously. And not just the evil “out there,” but the evil “in here.” The moment Christians refuse to take evil seriously is the moment Christ’s sacrifice begins to be robbed of its significance. Perhaps the cultural shift toward post-secular self-expression is why fewer good horror films are made today. We have eroded the pervasiveness of evil, and therefore goodness seems lethargic, toothless, and enfeebled. It is harder to reconcile the Christ of Revelation with the Jesus who plays so frequently across our television screens because, according to the latter, goodness must be only tolerant and not intolerant of evil. Yet the Lamb came and was slain. The Lion of eschatology, however, shows up in Revelation with an axe to grind against evil, and He does not seem too willing to roll over for anybody.

A well-meaning Christian once asked me, “Would you be comfortable watching a horror movie with Jesus?” Perhaps without thinking, I blurted out, “Lady, I think Jesus watches a few horror movies play out every day.” While I freely admit the point could have been better articulated, the kernel of truth that provoked my response has only become more pronounced to me as the years have passed.

Let me explain. Judith Halberstam is an American academic who wrote of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, “By focusing upon the body as the locus of fear, Shelley’s novel suggests that it is people (or at least bodies) who terrify people, not ghosts or gods, devils or monks, windswept castles or labyrinthine monasteries. The architecture of fear in this story is replaced by physiognomy, the landscape of fear is replaced by sutured skin, the conniving villain is replaced by an antihero and his monstrous creation.”18 Judith is now Jack Halberstam — but only sometimes, as she/he cannot seem to decide one way or the other. Please understand that this is not me being facetious. Judith/Jack actually does refuse to decide if she/he is a “she” or a “he.” Let her/him tell you herself/himself. “So some people call me Jack, my sister calls me Jude, people who I’ve known forever call me Judith — I try not to police any of it. A lot of people call me he, some people call me she, and I let it be a weird mix of things and I’m not trying to control it.”19

Take a quick look around America, circa October 2023. See the things our culture prioritizes, accepts, rejects, and finds intolerable. Perhaps you will conclude, like I do, that if Judith/Jack was right in her/his analysis of Frankenstein, then we are living in Mary Shelley’s nightmare. —Cole Burgett

Cole Burgett is a graduate of Dallas Theological Seminary and the Moody Bible Institute. He teaches classes in systematic theology and Bible exposition and writes extensively about theology and popular culture.

NOTES

- Michael Mallory, Universal Studios Monsters: A Legacy of Horror (New York: Universe Publishing, 2021), 11.

- Mordaunt Hall, “Bram Stoker’s Human Vampire,” New York Times, February 13, 1931, https://www.nytimes.com/1931/02/13/archives/the-screen-bram-stokers-human-vampire.html.

- Gundolf S. Freyermuth, “Despite His Fate, He Found His Fortune,” Los Angeles Times, September 14, 1997, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1997-sep-14-ca-32000-story.html.

- The Lost Son was released in October 2022 and can be heard on all major listening platforms. For more information, please visit the series website: https://thelostson.buzzsprout.com.

- Sam Borowski, quoted in Scott Essman, “Indie Filmmakers Examine the Legacy of Creature from the Black Lagoon,” Below the Line, October 30, 2015, https://www.btlnews.com/commentary/director-series/indie-filmmakers-examine-the-legacy-of-creature-from-the-black-lagoon/.

- Mallory, Universal Studios Monsters, 65.

- Terrence Rafferty, “Celebrating Boris Karloff, the Monster and the Man,” New York Times, February 3, 2006, https://www.nytimes.com/2006/02/03/movies/celebrating-boris-karloff-the-monster-and-the-man.html.

- John Potts, “What I Owe to Hammer Horror,” Senses of Cinema, Issue 47, May 2008, https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2008/feature-articles/hammer-horror/.

- Roger Ebert, “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre,” RogerEbert.com, originally published January 1, 1974, https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/the-texas-chain-saw-massacre-1974.

- Josh Bell, “The Start of the Slasher Film,” Novel Suspects, Hatchett Book Group (n.d.), https://www.novelsuspects.com/articles/the-start-of-the-slasher-film/.

- Manny’s filmmaking career has spanned over a decade, primarily focusing on the horror/thriller genres. This quote is included here with his permission.

- Stephen King, “Why We Crave Horror Movies,” Playboy (1981), retrieved from University of Massachusetts, Lowell, https://faculty.uml.edu/bmarshall/lowell/whywecravehorrormovies.pdf.

- Philip French, “The Bride of Frankenstein,” The Guardian, June 4, 2006, https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2006/jun/04/1.

- Lloyd Rose, “James Whale, the Man with a Monster Career,” Washington Post, November 29, 1998, https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/style/movies/features/jameswhale.htm.

- Rose, “James Whale, the Man with a Monster Career,” https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/style/movies/features/jameswhale.htm.

- For a good explanation of that difference and the way Scripture employs what might today be seen as “horror tropes,” see Brian Godawa, “An Apologetic of Horror,” Christian Research Journal, vol. 32, no. 5 (2009), https://www.equip.org/articles/an-apologetic-of-horror/.

- Mark Eckel, “Scared,” Comenius Institute, April 30, 2019, https://comeniusinstitute.com/2019/04/30/scared/.

- Judith Halberstam, Skin Shows: Gothic Horror and the Technology of Monsters (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1995), 28–29.

- Jack Halberstam, quoted in Sinclair Sexsmith, “Jack Halberstam: Queers Create Better Models of Success,” Lambda Literary, February 1, 2012, https://lambdaliterary.org/2012/02/jack-halberstam-queers-create-better-models-of-success/.