Listen to this article (15:28 min)

Please also see the following sidebar article that appeared within this article in Christian Research Journal, Volume 48, number 02 (2025), entitled, “‘Severance’ and the Good Life“.

This article was published exclusively online in the Christian Research Journal, Volume 48, number 02 (2025).

When you support the Journal, you join the team and help provide the resources at equip.org that minister to people worldwide. These resources include our ever-growing database of more than 2,500 articles and Bible Answers, as well as our free Postmodern Realities podcast.

Another way you can support our online articles is by leaving us a tip. A tip is just a small amount, like $3, $5, or $10, which is the cost of a latte, lunch out, or coffee drink. To leave a tip, click here.

(Editor’s Note: This article contains spoilers for

Seasons 1 and 2 of Apple TV’s Severance)

Television Series Review

Severance (Seasons 1 and 2)

Created by Dan Erickson

Primary Director: Ben Stiller

Executive Producers: Ben Stiller, Nicholas Weinstock, Jackie Cohn, Mark Friedman et al.

Producers: Aoife McArdle, Amanda Overton, Gerry Robert Byrne

Starring Adam Scott, Zach Cherry, Britt Lower, Tramell Tillman, Jen Tullock, Dichen Lachman, Michael Chernus, John Turturro, Christopher Walken, Patricia Arquette, Sarah Bock

Red Hour Productions and Fifth Season

Streaming on AppleTV+, 2022–

Rated TV-MA

“I am a person, and you are not.”1

—Helena Eagan

“He’s not dead, he’s just not here.”2

—Mark S.

Apple TV’s Severance (2022– ) has become a cultural phenomenon; it has spawned an abundance of media dedicated to interpretation and theorizing. Having recently wrapped its long-awaited, dynamite second season, the show is the epitome of artful, puzzle-box storytelling, with its tantalizing blend of mystery, surrealism, and philosophical speculation. It is maximally atmospheric, engaging the viewer with visuals and audio tracks that are striking in their originality — a tough feat in the contemporary entertainment industry. Virtually every detail of the world-building heightens the strangeness and intrigue and provides delicious fodder for the YouTubers and TikTokers who make up a portion of the show’s cult following. I, for one, will never again look at a deviled egg, a goat, or a marching band the same way.

A particular source of delight for Severance fans who have a philosophical bent is the host of personal identity issues raised by the titular technology — a brain chip that “severs” someone’s personal life consciousness (their “outie”) from their work life consciousness (their “innie”). The switch occurs when descending to, or ascending from, the “severed floor” at Lumon Industries. The outies and innies share no episodic memories, and thus the innies awake on their first day on the job at Lumon as semi-blank slates. They have no knowledge of life outside of their strictly controlled work environment, but they retain most of their impersonal semantic knowledge, which allows them to function socially and professionally. As the plot develops, we learn that three of the central characters — Mark S., Irving B., and Dylan G. — have all chosen to undergo severance as a way of coping with painful personal life circumstances: intense grief, abject loneliness, and recurrent career failure, respectively. How does this assuage the outies’ pain? They seem to believe that being psychologically anesthetized for most of their waking hours Monday through Friday will eventually “trickle down” (or out, in this scenario) and work on a subconscious level to help mitigate their emotional anguish.3

From the first episode of Severance, viewers are subtly prompted to consider whether the severance procedure, which generates a new, individual consciousness, is essentially producing another unique personal identity. In other words, is the innie a person in his or her own right who merely happens to share a body with his or her outie, or is there still only one person, but one whose mind can be artificially fragmented with strictly compartmentalized consciousnesses? Does each consciousness have its own immortal soul? In the show, there is ambiguity; perspectives seem to differ between characters and much is left to viewer interpretation. Severance may be science fiction, but like the better stories of that genre, it’s a useful (and highly entertaining) framework for philosophical discussions, especially those related to our humanity. In what follows, I will explore the issue of diachronic identity — the continuity of identity over time — to cast light on the questions above and to support the traditional Christian understanding of human nature: that we are body-soul dualities.

PERSONAL IDENTITY

How to account for the continuity of identity over time has been a perennial topic of debate in Western philosophy. John Locke (1632–1704) famously suggested that the condition of a person’s diachronic identity is the episodic memories by which we have conscious awareness of our own persistence over time.4 He writes that “as far as this consciousness can be extended backwards to any past action or thought, so far reaches the identity of that person; it is the same self now it was then; and ‘tis by the same self with this present one that now reflects on it, that that action was done.”5 Moreover, in his “waking and sleeping Socrates” illustration, Locke suggests that two persons can exist where there is only one man, if there are two distinct consciousnesses that are active in one body in an alternating fashion (in this case, daytime Socrates has a separate consciousness than nighttime Socrates).

A “two separate persons” view of the severed characters in Severance seems to basically track with Locke’s theory. Which of the two persons is conscious at a given time is dependent upon the spatial location of the body: either inside or outside the severed floor at Lumon. This raises interesting questions, such as what it really means when a severed character resigns, retires, or is terminated from Lumon — does the innie essentially die, since they will never be conscious again? The innies experience these events as the death of a colleague and friend, since they’ll never again see that person, and that person will never again have consciousness.

In the second season of the show, when Mark covertly begins the process of reintegrating his innie and outie consciousnesses, we learn that the innies and outies have mutually exclusive brain wave patterns.6 Both patterns are physically operational all the time, it’s just a matter of which one is permitted (by the implanted chip) to give rise to conscious awareness. The reintegration procedure involves syncing the brain waves and thereby achieving one unified consciousness. Does this mean that, when severed, there are two separate persons in the exact same spatial location and that the reintegrated person is a fusion of two persons? If a materialist account of personal identity is a facet of the Severance universe, then the answer, as absurd as it seems, would be yes, since the self would be identified by a set of physical brain state patterns.

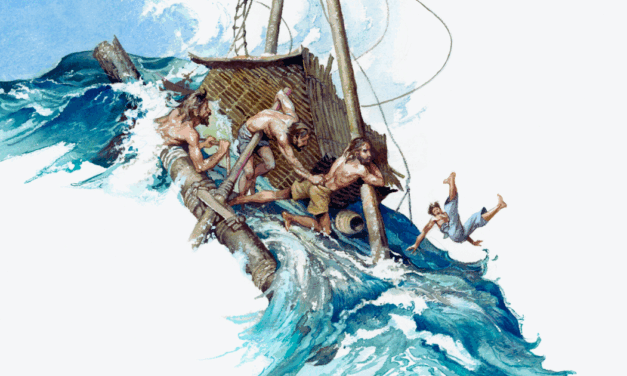

It remains to be seen whether the show’s storyline will resolve the question of whether innies and outies have their own unique personal identities. However, a materialist understanding of human persons is philosophically problematic for (among other things) the issue of diachronic identity. Two millennia ago, the Greek philosopher Plutarch reported a conundrum that, to this day, is a staple of introductory philosophy courses because it’s helpful in illustrating the problem.7 It’s commonly known as the Ship of Theseus paradox, and it concerns the question of whether the identity of a physical object remains the same over time despite the loss and acquisition of parts:

The ship on which Theseus sailed with the youths and returned in safety, the thirty-oared galley, was preserved by the Athenians down to the time of Demetrius Phalereus. They took away the old timbers from time to time, and put new and sound ones in their places, so that the vessel became a standing illustration for the philosophers in the mooted question of growth, some declaring that it remained the same, others that it was not the same vessel.8

After many years of maintenance, when every timber of Theseus’ ship had been replaced with a new one, was it still the same ship, the one that had belonged to Theseus? What if (as Thomas Hobbes suggested in the 17th century) all the discarded timbers were saved over the years and then reassembled into a thirty-oared galley in a separate location? Which ship would be Theseus’ ship? Typically, this paradox is used to show that grounding identity in a physical thing cannot succeed, since physical constitution changes over time. This is true with human beings, because the physical particles that constitute our bodies and brains do not remain the same ones thanks to metabolic processes and cell turnover. Tomorrow, your body will not have all the same particles that it has today. A forty-year-old person’s body does not have any of the same building blocks it had as a twenty-year-old. How, then, can we say that the forty-year-old is the same person who existed twenty years ago?

Earlier, we saw that John Locke regarded consciousness of our own enduring existence, which involves episodic memory, as the condition for diachronic identity. However, one of his most famous contemporaries, Thomas Reid, strongly disagreed and offered a thought experiment that exposes a flaw in the Lockean account (as he interpreted it). It’s known as the case of the Brave Officer, which Reid articulates as follows:

Suppose a brave officer to have been flogged when a boy at school for robbing an orchard, to have taken a standard from the enemy in his first campaign, and to have been made a general in advanced life; suppose, also, which must be admitted to be possible, that, when he took the standard, he was conscious of his having been flogged at school, and that, when made a general, he was conscious of his taking the standard, but had absolutely lost the consciousness of his flogging. These things being supposed, it follows, from Mr. Locke’s doctrine, that he who was flogged at school is the same person who took the standard, and that he who took the standard is the same person who was made a general. Whence it follows, if there be any truth in logic, that the general is the same person with him who was flogged at school. But the general’s consciousness does not reach so far back as his flogging; therefore, according to Mr. Locke’s doctrine, he is not the person who was flogged. Therefore, the general is, and at the same time is not, the same person with him who was flogged at school.9

What Reid is essentially demonstrating by way of the transitive law of logic is that lost memories cannot possibly mean that personal identity doesn’t extend back to forgotten life events. To be sure, an advanced dementia patient or someone with severe, permanent amnesia is still the same person even if they’ve lost their episodic memories or even all awareness of their earlier lives.

Given all of the above, it seems that neither physical nor psychological continuity are sufficient for grounding personal identity and providing a solid account for the persistence of one’s identity over time. What option remains? Many philosophers who endorse substance dualism (the view that we, as human beings, are not merely physical), argue that the only viable option is an immaterial soul. Since a soul is without parts and persists without physical change, it avoids the previously discussed problems associated with a material account of identity. Moreover, on substance dualism, neurological procedures, brain disease, and brain injuries that impact consciousness, memory, personality, and so forth do not create any philosophical difficulties concerning a person’s identity in the metaphysical sense. In the Severance universe, a reasonable philosophical conclusion about the personal identities of the severed characters would be that the procedure does not produce a second person; rather, it results in an extreme form of psychological fragmentation.

GENERATING SOULS THROUGH TECHNOLOGY?

Finally, a few words must be said about that dinner table conversation between outie Irving, outie Burt, and Burt’s partner, Fields. I, for one, was stunned that a major scene in the show featured a Christianity-related dialogue about the afterlife. Irving inquires how Burt came to work at the company, and Burt’s response is surprising to say the least: “Well, as a matter of fact, I was guided to Lumon’s door by Jesus.”10 In response to Irving’s apparent bafflement, Burt and Fields go on to explain that the severance procedure was a strategy to get a version of Burt into heaven. The year before, while attending a service at their Lutheran Church one Sunday, the pastor had given a sermon on severance in which he said (according to Fields) “that the church’s stance is that innies are complete individuals with souls. They can be judged separately from their outie.”11 The idea seems to be that, somehow, the severance procedure results in the creation of a second immaterial soul with its own moral culpability. Of course, this scene is highly problematic on a theological level, because it presents a false gospel: the assertion that being granted eternal life in heaven depends upon your earthly behavior, that one must earn their way by being a good person. This is contrary to orthodox Christianity, which teaches that salvation is a gift one receives by God’s grace when placing one’s faith in Christ, it is “not a result of works, so that no one may boast” (Ephesians 2:9 ESV).

Hypothetically, if something like the fictional severance technology could be scientifically achieved, it would indeed raise questions about where moral responsibility rests if the new consciousness, unbeknownst to the original, carried out a terrible deed of some sort. This opens up a philosophical and theological can of worms that would take us well beyond the scope of this article. Perhaps a reasonable Christian response would be that psychological fragmentation caused by artificial manipulation of the brain would be akin to the mental dysfunction caused by disease or injury. The new consciousness produced by the procedure would essentially be an abnormal psychological state. However, unlike a person with a diseased or injured brain, someone consenting to a severance-type procedure would be, it seems to me, responsible for all of their “unconscious” actions, just as someone acting under the influence of an inebriating substance is accountable for any harm they inflict even when they’ve sobered.

SCIENCE FICTION AND APOLOGETICS

In our technology-driven society, where science is considered by many to be the crown of human knowledge and achievement, the genre of science fiction can be tremendously effective in sparking conversations about philosophical and theological issues, such as those discussed here. Severance has certainly attained a high profile in current pop culture, which means it has great potential in the project of cultural apologetics. Many people are talking about it, and there’s ample opportunity for believers to interact with nonbelievers by chiming in on Substack, YouTube, and podcast comment threads and by producing original content that offers a Christian perspective on the show. I, for one, am convinced that science fiction, as a genre, is a supremely useful form of imaginative apologetics, and I’ve used sci-fi stories in seminars and courses I’ve taught with great success. Thus, it is a fascinating irony that some of the mid-20th century “fathers” of modern sci-fi were scientific materialists and that the genre was, from the outset, a major imaginative vehicle for promoting that worldview. As such, it amassed an enormous following among atheists and agnostics enamored with scientific speculation about humanity’s future and longevity. Suffice it to say, this dynamic is alive and well, and this presents a golden opportunity for the Christian apologist.

Melissa Cain Travis, PhD, is a Fellow with Discovery Institute’s Center for Science and Culture. She is the author of Thinking God’s Thoughts: Johannes Kepler and the Miracle of Cosmic Comprehensibility (Roman Roads Press, 2022) and Science and the Mind of the Maker: What the Conversation Between Faith and Science Reveals about God (Harvest House Publishers, 2018).

NOTES

- Severance, season 1, episode 4, “The You You Are,” created by Dan Erickson, directed by Aoife McArdle, written by Kari Drake, Dan Erickson, Anna Ouynang Moench, Red Hour Productions and Fifth Season, distributed by Apple TV+, released March 4, 2022.

- Severance, season 2, episode 5, “Trojan’s Horse,” created by Dan Erickson, directed by Samuel Donovan, written by Dan Erickson and Megan Ritchie, Red Hour Productions and Fifth Season, distributed by Apple TV+, released February 14, 2025.

- Early in the first season, Mark tells his sister Devon that the job is helping him with his grief, and in the second episode of the second season, his Lumon supervisor remarks to (outie) Mark: “The solace you have given him down there will make its way to you. It just takes time.” Severance, season 2, episode 2, “Goodbye, Mrs. Selvig,” created by Dan Erickson, directed by Samuel Donovan, written by Mohamad El Masri and Dan Erickson, Red Hour Productions and Fifth Season, distributed by Apple TV+, released January 24, 2025.

- Note that some interpret Locke as saying that consciousness constitutes personal identity, while others interpret him as saying that episodic memory is an essential aspect of identity.

- John Locke, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, abridged and edited by Kenneth P. Winkler (Hackett Publishing Company, 1996), 138.

- As a side note, viewers are clued in to the fact that the severance procedure isn’t exactly perfected. For instance, Irving’s outie obsessively paints the same image over and over again — a dark, mysterious hallway ending at an elevator that, unbeknownst to him, exists on Lumon’s severed floor.

- It is believed that this thought experiment dates back to the Presocratics, possibly originating with Heraclitus (fl. 500 BC).

- Plutarch, Lives, vol. II: Theseus, ch. 23 § 1, trans. Bernadotte Perrin (Harvard University Press; London: William Heinemann, 1914), 48–49.

- Thomas Reid, Essays on the Intellectual Powers of Man, abridged and edited by James Walker (John Bartlett, 1851), 248–249.

- Severance, season 2, episode 6, “Attila,” created by Dan Erickson, directed by Uta Briesewitz, written by Erin Wagoner and Dan Erickson, Red Hour Productions and Fifth Season, distributed by Apple TV+, released February 21, 2025.

- Severance, season 2, episode 6, “Attila.”