This article first appeared in the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL, volume 35, number 06 (2012). The full text of this article in PDF format can be obtained by clicking here. For further information or to subscribe to the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL go to: http://www.equip.org/christian-research-journal/

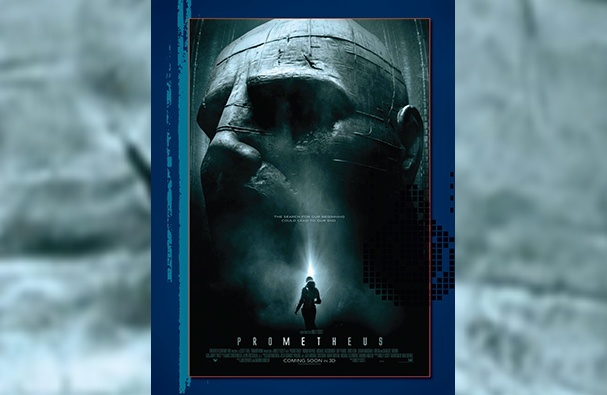

The great questions of life echo through the centuries: Where did we come from? Why are we here? Is there any meaning to life? Does God exist? Are we alone in the universe? Director Ridley Scott explores these questions in his gritty science fiction film Prometheus, which serves as a prequel of sorts to his famous “Alien” movies.1 With a screenplay coauthored by Damon Lindelof of Lost fame,2 the intriguing plot involves mysterious clues that lead a band of intrepid scientists on a mission about human origins and the truth about existence. They travel to the far reaches of space, following a map left behind by unknown alien visitors, and arrive on an uncharted planet where they soon discover ancient artifacts, uncover disturbing secrets, and run for their lives in terror.

But why should Christian apologists care about the latest R-rated science fiction film? Are there any particular reasons it warrants our attention? As I’ve expressed elsewhere, film and television are the “new literature.”3 Having largely shifted from a “Have you read?” culture to one that asks, “Have you seen?” we would do well to pay close attention to the influence of popular culture on faith-related matters. Moreover, as the battle between worldviews continues, ideas that were once on the fringes or scattered here and there in academia begin to filter their way into popular culture. As they do, it is better to be prepared and ready to give an answer (1 Pet. 3:15) than to be ignorant and unable to respond intelligently. Prometheus touches on questions relevant to human origins—an important topic that currently has drawn attention via ongoing debates between those who seek naturalistic explanations and those who point to signs of intelligence (most notably the Intelligent Design movement).

The goal is not to embrace culture uncritically, but neither is it to entrench ourselves within a sequestered Christian worldview cocoon. Rather, the contemporary apologist must seek to intelligently engage culture at all levels, including via interaction with films. This involves learning to exegete the medium, which entails careful interpretation and evaluation. With this backdrop in mind, this article will explore the apologetically relevant issues found in Prometheus.

GODS IN SPACE

Prometheus harkens to the tale of Greek mythology, wherein the eponymous demigod steals fire from the gods and returns it to humanity. Punished for this insubordination, Prometheus suffers an agonizing and endless fate (he is chained to a rock and his liver is eaten repeatedly by an eagle). Prometheus the film mentions briefly the deeds of the mythological Greek, but in the film it is the vessel of exploration that is named Prometheus.

After finding a series of clues in cave paintings all over the Earth, scientists conclude that ancient alien visitors have left a map to their world—an invitation, they believe, for a rendezvous with aliens. A wealthy and aging benefactor, Peter Weyland of the powerful Weyland Corporation, funds the expedition. He literally hopes to meet his maker and, in essence, have a conversation with his creators. One scientist in particular, Elizabeth Shaw, believes these aliens may hold answers to questions about the origins of human life. Specifically, Shaw believes the aliens have deliberately engineered life on earth.

HUMAN ORIGINS AND DIRECTED PANSPERMIA

The idea that intelligent life beyond our planet “seeded” life or directed it in some way is one theory some scientists believe can successfully explain questions about human origins. Known as directed panspermia, the idea is that life on earth did not emerge spontaneously by a combination of chance and time, but, rather, that it was jumpstarted, so to speak, by extraterrestrial influence. Lest readers think this idea is the stuff of wild science fiction, there are examples of respected scientists holding to this viewpoint. Francis Crick, for instance, known for his codiscovery of the structure of DNA, holds to the position. Prominent atheist Richard Dawkins also acknowledged the possibility during an interview in the documentary Expelled: No Intelligence Allowed.

Unable to explain human origins adequately due to the many complexities involved in attributing it only to naturalistic processes, directed panspermia avoids having to explain human origins and instead opts to place the rise of human life in extraterrestrial sources. We will return to this theory later as we seek to evaluate the ideas presented in Prometheus.

EPISTEMOLOGY: IS THE TRUTH OUT THERE?

A famous science fiction television series, The X-Files (1993–2002), often stated, “The truth is out there,” as well as, “I want to believe.” Prometheus also grapples with these issues of knowledge or, technically speaking, epistemology. The main character, Dr. Shaw, is presented as a believer in God. She wears a cross, for instance, which she values highly. Her cross becomes a sort of recurring theme in the movie, which seems to pit faith and reason against one another.

At any rate, Shaw’s memories include a discussion with her father about what happens when people die. Do they go to heaven? Paradise? How do we know? Her father states that he believes what he believes because “that’s what I choose to believe.” Questions about how we know what we know, or even if we can know anything at all, are incredibly relevant to apologetics. A robust epistemology can strengthen our faith, providing us with justified true belief about reality, while a weak epistemology can lead to the disintegration of faith without a foundation.

DEISM: HAS GOD ABANDONED US?

In addition to the themes already mentioned, Prometheus also poses questions related to abandonment. Specifically, if God exists, has He abandoned humanity? Are we essentially on our own in the universe? If so, even if God does or did exist, we may as well live as though naturalism is true. Peter Weyland wants answers before he dies. In actuality, he’d prefer immortality, but if the best he can do is meet his maker, at least he can ask some poignant metaphysical questions. There is a sense of abandonment in Prometheus, too, as though the creators or engineers responsible for the origins of life on earth wound up the clock of life, yet left it to run on its own. This, incidentally, is the classic description of deism—the worldview that acknowledges the reality of a creator God, but believes this God no longer has an interest in the world that He created.

Prometheus even goes so far as to suggest that God, or at least the alien engineer “gods,” hate their creations. It is stated that “everyone wants their parents dead.” Although the statement is a false hasty generalization, it does express the metaphysical underpinnings of Prometheus, which suggest tensions between Creator and creatures. Human beings inherently seek meaning and explanations, but according to Prometheus such meaning is in the end elusive, offering no real answers to the great questions of life. Ultimately, the crew of the ship Prometheus sacrifices itself in order to stop their alien progenitors from leaving the planet on a mission to destroy humanity. God, then, symbolically dies at the hands of His creations.

THE CROSS AND CREATION: EVALUATING PROMETHEUS

Given the rich philosophical and theological fodder found in Prometheus, there are multiple opportunities for apologetic engagement. Will we find God in outer space? C. S. Lewis pondered this question decades ago in an essay originally titled, “Will We Lose God in Outer Space?”4 The essay seeks to address what implications there might be for Christian theism if intelligent life is discovered on other worlds, as well as whether or not we are the only fallen creatures in the universe, and the implications to God’s plan of redemption. Lewis, incidentally, suggests the vast distances between heavenly bodies in space may be God’s means of quarantining the troublemakers (us), lest we infect unfallen creatures scattered about the cosmos. In any event, we need not travel to distant locales in outer space in order to find God. Indeed, according to Christian theism, God has found us. Evidence for God’s existence is ample and found both in general revelation (e.g., creation and human moral conscience), as well as special revelation (via the person of Christ and the pages of the Bible).

What, then, of the suggestion in Prometheus that human life was the direct result of directed panspermia? There are multiple flaws with this theory, not the least of which is the fact that it is completely ad hoc and based on no empirical evidence whatsoever. But apologist Douglas Groothuis points out one of the most severe deficiencies: “Crick’s far-fetched explanation merely pushes back the question of life’s origin one step. If intelligent beings planted life on earth, where did they come from? Terrestrial abiogenesis is ‘solved,’ but extraterrestrial abiogenesis remains unsolved.”5 Even Shaw responds along these general lines when she asks of the alien engineers, “Who made them?” A far better explanation of the complex origins of sophisticated, rational human beings is found in God the Creator and Designer, not in a mixture of chance and time.

What of knowledge? Isn’t real knowledge beyond our capabilities? Can we really know? The epistemology of Prometheus is weak at best. Is what we “choose to believe” true? That’s hardly a firm foundation for belief in anything. What if one chooses to believe that a triangle has four sides or that an elephant can balance itself on a toothpick? What if one chooses to believe that God does not exist (atheism) or that an impersonal life force permeates all of reality (pantheism)?

Merely choosing to believe is not a solid epistemology by any means. A better course of action is to seek the best explanation. Does a particular belief one holds to correspond with reality or not? If we believe it does, what evidence do we have in support of such a belief? Is our belief justified? Is it true? What possible counterexamples, defeaters, or refutations of the belief exist, and are they convincing? The ability to test worldview claims, including testing our own worldview claims, is important and something we should strive to do. After all, if Christianity is really “true and reasonable” (Acts 26:25 NIV), then it should stand up to scrutiny of all kinds.6

How, though, are we to respond to claims of deism or God’s alleged abandonment of His creation? Prometheus does not offer a clear explanation for why the alien engineers abandoned human beings or why the “gods” are so eager to destroy their creations. It may be that their experiments on the dangerous aliens (of the Aliens movies) have caused the engineers to reconsider their meddling in the affairs of other worlds, lest their own creations turn on them or ravage the universe.

Whatever the case may be, the underlying implications suggested by Prometheus lead to deism—a God who exists, but who no longer has any interest in His creation—or naturalism. If deism is true, then there is cause for concern. Why would God create us and then abandon us? Deism, however, is flawed on many levels, not the least of which is the positive evidence in favor of God’s existence, as well as His deliberate involvement in human history. In systematic theology terms, we would say that God is transcendent, yet active or immanent in His creation. This means that God is actively involved in the world, providentially and purposefully directing history.

WE ARE THE PRODIGALS

Far from being distant or abandoning us, God through Christ reaches out to us by offering redemption and reconciliation. But we are like the prodigal son of Christ’s famous parable. We are the ones who have turned away from God and sought our own path, apart from His truths. Deism and naturalism can both lead to nihilism—a worldview of despair over the lack of meaning to reality. We are prodigals, shaking our fists at the god who is dead, yet something within us tells us that He is very much alive.

Even Shaw at the end of Prometheus is not without hope. As she describes her quest for truth and meaning, she says she is “still searching.” Christ Himself said, “So I say to you: Ask and it will be given to you; seek and you will find; knock and the door will be opened to you” (Luke 11:9 NIV). Insights from the apostle Paul also apply when he speaks of God creating humans so that they “would seek God, if perhaps they might grope for Him and find Him, though He is not far from each one of us” (Acts 17:27 NASB).

Robert Velarde is author of The Wisdom of Pixar (InterVarsity Press), Conversations with C. S. Lewis (InterVarsity Press), The Heart of Narnia (NavPress), and more. He received his M.A. from Southern Evangelical Seminary and contributed to Don’t Stop Believin’: Pop Culture and Religion from Ben-hur to Zombies (Westminster John Knox, 2012).

NOTES

- In addition to Alien (1979, directed by Ridley Scott), Aliens (1986, directed by James Cameron), and Alien: Resurrection (1997, directed by Jean-Pierre Jeunet), the science fiction world of Ridley Scott’s alien films has also spawned other franchises including various Aliens versus Predators movies.

- See Robert Velarde, “The Gospel according to Lost,” in Christian Research Journal 30, 1 (2007).

- See, for instance, my articles, “Film Is the New Literature” (available at http://www.patheos.com/Resources/Additional-Resources/Film-Is-the-New-Literature.html) and “Television as the New Literature: Understanding and Evaluating the Medium,” Christian Research Journal 33, 4 (2010): http://www.equip.org/articles/televisionas-the-new-literature-understanding-and-evaluating-the-medium/.

- Retitled “Religion and Rocketry” and available in C. S. Lewis, The World’s Last Night and Other Essays (San Diego: Harcourt Brace, 1960).

- Douglas Groothuis, Christian Apologetics (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2011), 322.

- On testing worldview claims, see Groothuis, 52–60.