Listen to this article (16:08 min)

This article was published exclusively online in the Christian Research Journal, Volume 47, number 03 (2024).

When you support the Journal, you join the team and help provide the resources at equip.org that minister to people worldwide. These resources include our ever-growing database of more than 2,000 articles, as well as our free Postmodern Realities podcast.

Another way you can support our online articles is by leaving us a tip. A tip is just a small amount, like $3, $5, or $10, which is the cost of a latte, lunch out, or coffee drink. To leave a tip, click here

**Editor’s Note: This article contains spoilers for several Christopher Nolan films.**

Christopher Nolan’s Dunkirk (2017) tells the story of the heroic rescue of over 300,000 soldiers from the beaches of France. Though the battle and rescue are notable as a strategic retreat, the film captures the valor of soldiers and citizens as they rally against a powerful enemy. Dunkirk concludes with a quote from Churchill’s 1941 stirring, mid-war speech about the event: “We shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be. We shall fight on the beaches. We shall fight on the landing grounds. We shall fight in the fields and in the streets. We shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender.” Though now surpassed by the critical success of Oppenheimer (2023), which won Christopher Nolan best picture and best director, Dunkirk highlights a central concern in the director’s work: the fight to defend one’s little island against a hostile world.

In Dunkirk, the island and the forces it opposes are quite literal. England, Nolan’s native home, must give its all to stand against the titanic aggression of Hitler’s army. But in most of Nolan’s films, the conflict is often shifted into an existential or philosophical register. Among contemporary blockbuster filmmakers, Nolan stands out as the most contemplative. His movies aren’t just high-concept, they are also highly conceptual. Rooted in genre conventions, Nolan has invented some of the most ingenious twists on standard tropes: a film-noir about a detective with memory loss, told backwards; a heist set inside the world of dreams; a “Bond film” filled with time reversal. But the thoughtfulness doesn’t stop at the conceit, Nolan is thinking about a set of concerns that run deep into the heart of his movies. Specifically, Nolan is obsessed with the heroic and often tragic struggle to preserve some shred of hope and meaning.

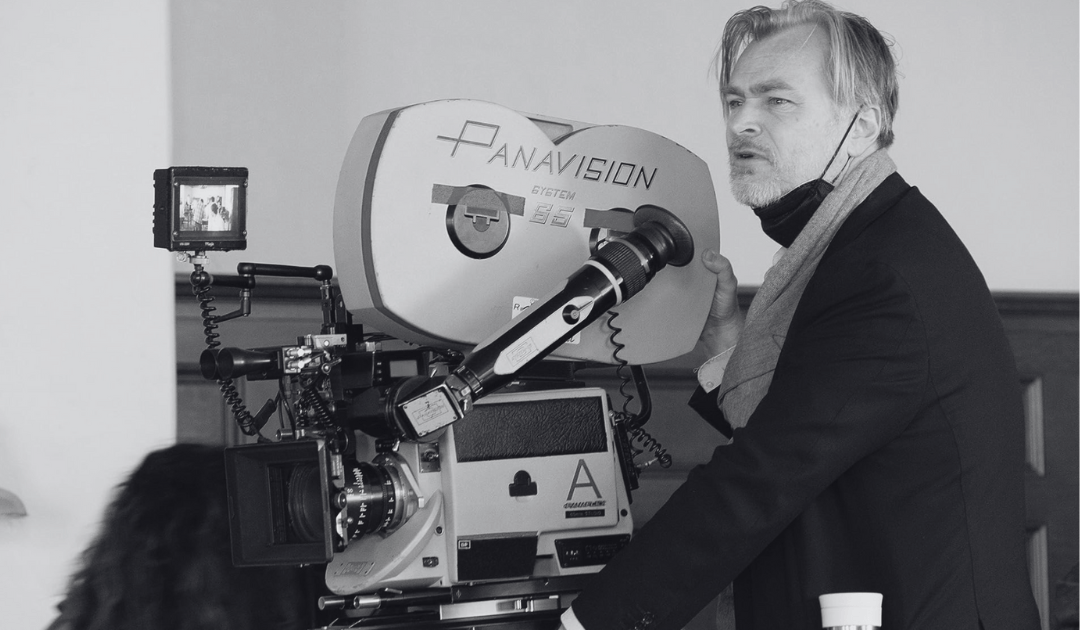

Attending to the themes that run through Nolan’s films seems self-evidently valuable. He’s a true auteur. Serving as a writer (credited or not) on his movies, his movies show a strong shared similarity of interests and style. He’s also the seventh-highest grossing director of all time.1 His last film, Oppenheimer, won the Oscar for best picture (though it did lose to Barbie (2023) in the ‘Barbenheimer’ battle for box office). He kicked off the recent Hollywood obsession with superhero films and The Dark Knight (2008) is regarded by many as the best superhero movie ever made.

Nolan also exerts a power in Hollywood few directors possess. In 2014, he led the charge to preserve film as an option for Hollywood productions and won. He pioneered the use of Imax in feature films. There are few directors with as strong a track record as Nolan, whose films are a source of immediate buzz just by association with his name. Notoriously private, Nolan’s next film is still a source of speculation. Perhaps it will be a Bond reboot or a remake of the British TV series The Prisoner (1967–1968). No one knows. But if a new 007 film is announced as his next project, the name most discussed will likely be Nolan, Christopher Nolan.

The Early Noir Films. Nolan’s early films were smaller in scale, and fit within the genre of film noir, observing flawed heroes as they navigate mysteries surrounded by shady characters. Following (1998), Memento (2000), and Insomnia (2002) tracked troubled and lonely men as they wrestled with their own obsessions. Following tells the story of a young writer drawn under the spell of a charming burglar, who eventually frames him for murder. Memento, the film that announced Nolan to the world, features a protagonist with retrograde amnesia (meaning he cannot form new memories) as he attempts to track down his wife’s killer. Told in reverse chronological order, the film’s jumps back in time simulate the experience of perpetual short-term memory loss. Insomnia’s detective flies to Alaska, where his hunt for a killer is haunted by his own ethical failures as a policeman. The perpetual light of midsummer Alaska, combined with his own guilty conscience, keeps the detective awake for days on end. His only confidant is the killer who taunts him with knowing phone calls.

Film noir has always been angsty and morally ambiguous. But Nolan’s entries add an existential twist. Memento and Insomnia give us heroes that must wrestle with the meaning of their lives. They thought that they were brave soldiers fighting back the injustice of the universe, only to recognize that they are guilty as well. In Memento, discovering that his wife’s killer has been caught and killed years before, the main character decides to keep on deluding himself. This is easily accomplished, as he will soon forget his own self-deception. In Insomnia, the story takes a more hopeful turn, as the dying detective orders that his crimes be revealed to keep a younger policewoman from following in his footsteps. The underlying tension of both films is between a hopeful quest and the tragic reality.

Batman Trilogy. Nolan’s interest in noir served him well as he transitioned to the superhero genre. The dark and brooding Batman trilogy pits a lone vigilante against a corrupt city. Armed with advanced technology and a Churchillian resolve, Bruce Wayne sets out to instill fear in the hearts of Gotham’s criminals. An underlying theme in the Batman movies is deception. To become more than a mere man, Wayne must become a symbol, masking his identity to protect the ones he loves. Longing for a normal life, but unable to resist his quest to fight crime, Batman Begins (2005) ends with Bruce’s childhood love telling him that the face he presents to the public, billionaire playboy, is actually the mask he wears.

The Dark Knight amplifies the theme of deception when it concludes with the coverup of Harvey Dent’s death. Batman takes the blame for a series of vigilante murders and the public is given a hopeful lie to inspire them. The Dark Knight Rises (2012) exposes the lie, with terrible consequences. It concludes on a more hopeful note, with Gotham saved and Batman appearing to die sacrificially. But this too is a deception. Bruce Wayne uses the ruse to start the kind of new life he longed for in the first film. As with Memento and Insomnia, the Batman trilogy offers us an obsessed detective fighting for a cause, facing the deadly conflict between reality and hope.

Sci-Fi. In the midst of directing the Batman movies, Nolan directed two science fiction films of a sort. The Prestige (2006) centers on two warring stage magicians, which sounds a bit like a comedy, but is a somber and tragic film. Magic presents Nolan with a fitting metaphor for the creative act itself, as the magicians see their own sacrifices as a service to the world. “You never understood why we did this,” one magician says to the other, “The audience knows the truth: the world is simple. It’s miserable, solid all the way through. But if you could fool them, even for a second, you can make them wonder, and then you got to see something really special.”2 Stage magic is the art of deception for the sake of a beautiful effect, but the truth of the trick, like the lives of the magicians in the film, is disenchanting once learned.

Inception was Nolan’s most experimental film at the time, and his most successful original project. A heist movie set inside the world of dreams, Inception is at once a reflection on the filmmaking process, a highly complex thriller, and a meditation on the value of truth. With the aid of an underexplained technology that allows one to invade others’ dreams, the main character is plagued by fears that he is stuck in a reality of his own creation. Much of the film centers around the question of why we would return to the real world if we can be satisfied with a dream. One character asks, “Who would wanna be stuck in a dream for ten years?” Another replies, “It depends on the dream.”3

A master of the art of designing simulated architecture within the dream world, the main character is at once haunted by his own abuse of the dream world and also still in awe of the power of the imagination. In a key scene, he explains to a novice how dreams work: “Dreams, they feel real while we’re in them, right? It’s only when we wake up that we realize how things are actually strange. Let me ask you a question, you, you never really remember the beginning of a dream do you? You always wind up right in the middle of what’s going on.”4 The scene is brilliant, because it serves as a metaphor for the art of cinematic storytelling. The very scene we are watching seems real enough when we cut to it, just a conversation at a cafe that we do not question because we understand the language of cinematic storytelling. Then the illusion shatters as we realize the scene we are watching is set in the dream world. Thoughtful moviegoers will also reflect that good movies feel real while we are watching them. They are a kind of shared dreaming. In Nolan’s mind, it seems, they are a magic trick.

Inception’s famous conclusion leaves open the question as to whether the dream has ended, or is still ongoing. Able at last to return to his happy home, his own little island, the main character ignores his only sure sign that he is not dreaming, choosing instead to embrace his children. A good argument could be made that he is not dreaming in the end, but that is beside the thematic point. Once again, Nolan has given us an embattled hero, fighting his way home, torn between hope and reality. Like the idea that the crew of dream invaders seek to plant in the mind of their mark, Nolan has incepted, once again, a big question about the value of truth.

Nolan’s next movies expand the scale and scope of conflict, each dealing with world-ending possibilities. Interstellar (2014), a much more hopeful film, follows a team of explorers as they try to find a new home for humans among the stars. As with other Nolan movies, there’s the deception theme. Back on Earth, scientists are spurred on by the possibility of a scientific formula that will enable large vessels to rescue humans from their dying planet. The people of Earth are, like the men on Dunkirk beach, “hoping for deliverance.”5 But the scientific formula is a noble lie, as in The Dark Knight or Plato’s Republic, it provides hope but not truth. The scientist who created the plan to escape Earth knew that the only way people would support the interstellar mission is if they thought they could be saved as well. One character describes the scientist’s lie this way: “He was prepared to destroy his own humanity in order to save the species.”6

The hopeful turn occurs when the main character discovers a tesseract that enables him to transmit the needed information to complete the formula, saving the people of Earth. Who built the tesseract? Future humans assisting those in the past to save humanity. Unlike the film it most closely resembles, Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), no extraplanetary entities can be found in Nolan’s films. There are no gods, aliens, or even magic. Perhaps this is most notable in his superhero films, where there are no special superpowers: just technology, intelligence, and a fighting spirit. It’s just us, and so it is up to us to “rage against the dying of the light,”7 which Interstellar quotes.

Tenet (2020) is, without a doubt, Nolan’s most ambitious film. Playing with the possibility of inverting entropy, allowing characters to move backwards through time, the movie outsmarted many audiences. Rewatching it recently, the film’s chronological craziness makes conceptual sense but resists understanding. Since I wrote about this movie for this Journal,8 I’ll skip a summary. But suffice it to say that the usual themes are all here. Truth is dangerous. Heroic sacrifice is needed. And we are our own best hope and worst enemy.

Fighting for the Preservation of This Island Earth. As with Interstellar, Dunkirk, and Oppenheimer, Nolan has shifted to taking on worldwide threats. In Tenet, the possibility of worldwide extinction looms over the film. Because it is filled with science fiction craziness, the concerns of Tenet offer a comfortable distance from this-worldly threats. Not so with Oppenheimer, which may be Nolan’s most mature and darkest film to date. Tenet also pits a world-destroying antagonist against a world-saving protagonist, but Oppenheimer presents us with duality in one, titular figure. Like the heroes of Memento or Insomnia, Oppenheimer is a hero that teeters on the edge of becoming a villain.

Based on the biography by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, American Prometheus (Vintage Books, 2006), Nolan’s best picture winner is in awe of the magnificent achievement of Robert Oppenheimer’s brilliance as he leads the team of scientists that created the atomic bomb. Yet it is also haunted by the nightmare of a world now in possession of the ability to destroy itself. The film revels in the genius of modern physics and the ingenuity and craft that Oppenheimer, like a great film director, organizes toward a seemingly impossible task. While Interstellar, Dunkirk, and Tenet take a moment to revel in victory, Oppenheimer cannot delight in the ending of the war even for a moment. Their victory is, as one character describes it, “the most important [expletive deleted] thing to ever happen in the history of the world!”9 But not for the reasons they hoped.

Here is where Oppenheimer differs from so much of Nolan’s other work. While the main character is inescapably caught up in his own imaginings, the film is not caught up in Nolan’s own imagination. He presents us with a true challenge we still face, and which his heroes cannot overcome or trick themselves into ignoring. It seems, in some significant way, an attempt by Nolan himself to fight for the preservation of this island Earth. However, much like the protagonists in many of his films, the problem of nuclear war presents us with an uncomfortable truth from which we are tempted simply to distract ourselves. Perhaps this is why Nolan has expressed eagerness to put Oppenheimer behind him.10

Previously I have described Nolan’s work as nihilistic. While I still think that there is a strain of nihilism running through his movies, it isn’t quite accurate to the whole of his filmography. Much like the atheist existentialists who sought to resist the nihilism of a hopeless world by the self-creation of meaning, Nolan’s heroes are often battling against the hostility of the universe as Nolan sees it. They have no other resources besides determination and intellect. Sometimes they win temporary victories, and sometimes they lose and must retreat to the safety of comforting illusions. But they always fight.

Philip Tallon is an Associate Professor of Theology at Houston Christian University. He’s on X: @oldhundreth.

NOTES

- See “Top Grossing Director at the Worldwide Box Office,” The Numbers, accessed July 9, 2024, https://www.the-numbers.com/box-office-star-records/worldwide/lifetime-specific-technical-role/director.

- The Prestige, directed by Christopher Nolan, written by Jonathan Nolan and Christopher Nolan (Burbank, CA: Buena Vista Pictures, 2006).

- Inception, written and directed by Christopher Nolan (Burbank, CA: Warner Bros. Pictures, 2010).

- Inception, written and directed by Christopher Nolan.

- Christopher Nolan, Dunkirk — The Complete Screenplay with Selected Storyboards (London: Faber and Faber Ltd., 2017), Scriptslug, accessed July 9, 2024, https://assets.scriptslug.com/live/pdf/scripts/dunkirk-2017.pdf.

- Interstellar, directed by Christopher Nolan, written by Jonathan Nolan and Christopher Nolan (Hollywood, CA: Paramount Pictures, 2014)

- Dylan Thomas, “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night” (1947).

- Philip Tallon, “Time May Change Me, But I Can’t Change Time: Reversing Time to Understand Christopher Nolan’s Tenet,” Christian Research Journal, March 9, 2023, https://www.equip.org/articles/time-may-change-me-but-i-cant-change-time-reversing-time-to-understand-christopher-nolans-tenet/.

- Oppenheimer, directed by Christopher Nolan, screenplay by Christopher Nolan (Universal City, CA: Universal Pictures, 2023).

- “Christopher Nolan Says He’s Ready to Move on from His ‘Important’ but ‘Dark’ Movie ‘Oppenheimer,’” Yahoo Entertainment, November 16, 2023, https://www.yahoo.com/entertainment/christopher-nolan-says-ready-move-130049665.html.