This article first appeared in the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL, volume 36, number 01 (2013). The full text of this article in PDF format can be obtained by clicking here. For further information or to subscribe to the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL go to: http://www.equip.org/christian-research-journal/

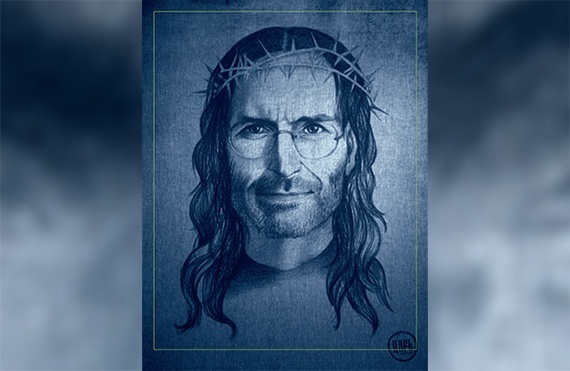

A colleague of mine at Denver Seminary noted that the release of the new iPad seemed to him to be something of a secular epiphany to those present at the televised Apple unveiling. In the style of the now-deceased Steve Jobs, the new Apple president unveiled technology’s latest revelation—and all were in awe of it; that is, they will be until the next version appears.

This spectacle of the transcendent revealing itself through technology would have been impossible without the person of Steve Jobs, a quirky and resourceful hippie who somehow envisioned technology as a path to meaning. Although he wrote no books, held no political office, and starred in no films, Jobs was one of the most influential people of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. These devices shape our souls (often unbeknownst to us). As Winston Churchill said, “We make our buildings, then our buildings make us.” But what made Jobs tick? What was his worldview, and should we follow it?

In the best-selling biography Steve Jobs, noted biographer Walter Isaacson recounts an event when the thirteen-year-old Jobs was distressed by a photograph in a 1968 issue of Life magazine. It showed a pair of starving children in Biafra, Africa, who were suffering because of a famine there. (I remember this myself, being roughly Jobs’s age.) Jobs, rightly disturbed by this tragedy, went to his Lutheran pastor for help. He held up one finger and asked, “Did God know I would hold up this finger before I did?” The pastor said, “Yes, God knows everything.” Of course, the pastor was correct (Ps. 139). Then Jobs produced the Life cover photo and asked, “Well, does God know about this and what’s going to happen to those children?” The pastor replied, “Steve, I know you don’t understand, but yes, God knew about this.” That was as far as the discussion went. The pastor offered no apologetic—no reason to believe in the gospel despite evil (1 Pet. 3:15)—to this young, brilliant, and inquiring soul. Isaacson reports that “Jobs announced that he didn’t want to have anything to do with worshiping such a God, and he never went back to church.”1

This account of Jobs’s irritated exit from the church is sadly comparable to one given by Marleen Winell, a counselor who assists people to leave religious groups and lead healthy secular lives. In Leaving the Fold, she reports of a young man named Sandy who was part of her “religious recovery support group.” As a young Christian college student, Sandy was troubled by the challenges to Christianity he encountered in the secular classroom. Distraught, Sandy went to his pastor, who tried to reassure him but gave no apologetic advice. Finally, Sandy, burning with intellectual desire, returned to his pastor, desperate for answers. The pastor cut Sandy short and said, “Sandy, it is time we call this what it is: sin.” Winell comments that Sandy never went back to the church, since he could not follow “a religion that made thinking a sin.”2 Although Sandy very likely did not have the global impact of Steve Jobs, he was haunted by a similar problem and was given a similar anti-intellectual answer by a clergyman. This should not be, since Christianity is a rational worldview worth defending through apologetics against rival worldviews and religions.3 This account from Jobs’s life and the fideistic response it invoked calls out for further discussion.

SUBSTITUTING BUDDHA FOR JESUS

While we know nothing of Sandy’s fate, Jobs pursued Buddhism, gurus, and hallucinogenic drug use,4 although his Buddhism (like many of his generation) was a bit à la carte and not doctrinaire. Jobs later told Isaacson that “the juice goes out of Christianity when it becomes too based on faith rather than on living like Jesus and seeing the world as Jesus saw it.” Jobs apparently wanted to separate a Jesus- inspired lifestyle (of Jobs’s preference) from any set of orthodox Christian beliefs. Yet had Jobs been serious about “living like Jesus,” he would have realized that Jesus taught and lived out a specific worldview, which Jesus articulated in no uncertain terms.

Unlike the Buddha, Jesus articulated clear ideas about the reality of God, and He made that reality the core of His teaching. As a Jew, He believed in the God of creation and personal covenant. In Jesus’ worldview, God, human liberation, and the history of Israel and the entire cosmos were closely related. Jesus, as opposed to Buddha, did not articulate a method of liberation that was agnostic or neutral with respect to great metaphysical questions. Although later Buddhist writings can be metaphysically sophisticated, and the Buddha was not entirely without a worldview, he considered questions about creation and divine reality to be unedifying. “The Blessed One” (the Buddha) would not speak to “whether the world is eternal or temporal, finite or infinite; whether the life principle is identical with the body, or something different; whether the Perfect One [the Buddha] continues after death.”5 Jesus, conversely, believed that substantial metaphysical knowledge was possible, desirable, and valuable—indeed vital—for spiritual liberation.

JESUS REACHES INTO OUR LIVES

Jesus’ public ministry commenced with His proclamation of the kingdom of God and its implications for life (Matt. 4:17). The key point of Jesus’ teaching on the kingdom is that God exists and is decisively involved in both human and cosmic affairs. All of Jesus’ teachings are organically related to His understanding of God. Without this concept of God, Jesus’ teachings unravel. According to Him, one’s knowledge of God is pivotal for one’s spiritual state, character, and destiny. During a theological dispute about the afterlife, Jesus rebuked some religious leaders by saying, “You are in error because you do not know the Scriptures or the power of God” (Matt. 22:29 NIV).

Jesus advocated a theistic worldview: there is one God who is (1) personal, (2) knowable, (3) worthy of adoration, worship, and service, (4) separate from the creation onto- logically, but (5) involved with creation through providence, prophecy, and miracle, despite the creation’s defacement through sin (see Rom. 8:18–26).6 This was intrinsic and inexorable to the teaching, living, dying, and resurrection of Jesus Christ. Jesus came as the incarnation of God, full of grace and truth, a man who “made the Father known” (John 1:1–14; see also Heb. 1:1–4), not as a mere sage giving advice for coping with a world of suffering, as did the Buddha.7

SUFFERING

While Christ recognized suffering, His approach to it was totally different than that of the founder of Buddhism, who advised that men detach themselves from the world to attain an ineffable state called Nirvana (which means what is left when a candle is blown out). Jesus knew of sin’s origin (in human rebellion against their Creator), its existential reality (especially as He experienced it in His Cross), and its conquest (through His resurrection, ascension, session, and second coming).8 Instead of trying to escape the world of suffering, we can fight against it in God’s power. As Francis Schaeffer said, we can fight evil without fighting God, since God is redeeming his errant creation through the unstoppable expansion of the Kingdom of God.9 “Therefore, since we are receiving a kingdom that cannot be shaken, let us be thankful, and so worship God acceptably with reverence and awe” (Heb. 12:28).

The book Steve Jobs reveals a brilliant man who, unlike Christ and the Christian ideal, seldom understood or entered into the pain of others. He viewed himself as an artist of technology, and everything else was subordinated to that identity. He wanted to leave a mark on the world. He did, although this hardly fits Buddhism, which desires the elimination of the ego, not its fulfillment. Reading his biography is often painful because of Jobs’s own unresolved suffering (perhaps much of it due to his being abandoned by his biological parents), and the suffering he inflicted on others. This is also ironic, since Buddhism strives for the elimination of suffering through becoming detached from the world of craving things in space and time. Isaacson alludes to a vexing conversation between Jobs and a girlfriend named Jennifer Egan. Egan astutely discerned that Jobs, the Buddhist, was contradicting his own philosophy by “making computers and other products that people coveted.” Egan says that Jobs was “irritated by the dichotomy”—as well he should, since it cannot be resolved on Buddhist terms.10

The most reliable records of Jesus’ life are the four Gospels of the New Testament.11 In them, we find Jesus affirming the existence of one, all-powerful God, as well as the existence of all manner of evil. That is how Jesus saw the world. But, unlike the Buddha, Jesus did not counsel His followers to detach from the world of suffering by ceasing to crave satisfaction. He rather said, “Blessed are those who hunger and thirst after righteousness, for they will be satisfied” (Matt. 5:6). According to Jesus, those who so hunger will also suffer: “Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted” (Matt. 5:4).

The evils of this groaning world did not deter Jesus from his mission to “seek and to save the lost” (Luke 19:10). It was this wounded and aching world that sent Jesus to a bloody and horrible death on a Roman cross, in order that humanity and deity might be reconciled and hope restored to an erring race of mortals. As Pascal said, “The Incarnation shows man the greatness of his wretchedness through the greatness of the remedy required.” Moreover, “Not only do we only know God through Jesus Christ, but we only know ourselves through Jesus Christ; we only know life and death through Jesus Christ. Apart from Jesus Christ we cannot know the meaning of our life or our death, of God or of ourselves. Thus without Scripture, whose only object is Christ, we know nothing and can see nothing but obscurity and confusion in the nature of God and in nature itself” (417, 548).12

If God is perfectly good and infinitely powerful (as can be credibly argued),13 He will not waste the sufferings of the world. He will bring a greater good out of them not otherwise possible. This may sound theoretical, but God Himself put flesh to that reality through the incarnation: “The Word became flesh and dwelt among us, full of grace and truth” (John 1:14). This was written by an eyewitness, the apostle John (see John 19; 20:9). That Word taught only truth, offered only love and justice, and was put to death for no legal reason. On His cross, Jesus forgave His accusers and finally said, “It is finished” (John 19:30). He was buried, dead as dead could be. The universe waited…until He rose from the dead three days later—never to die again. In this, and only in this, can rational hope be found for a world of suffering and death. As Paul confesses, our hope in the gospel “does not disappoint us, because God has poured out his love into our hearts by the Holy Spirit, whom he has given us” (Romans 5:5 NIV).

At a young age, Steve Jobs faced the severity and seeming absurdity of evil. In so doing, he rejected the only answer to the suffering: Christ Jesus, crucified and resurrected. Let us rather affirm with the apostle Paul, who dares to mock death in the face of his life in Christ: “Where, O death, is your victory? Where, O death, is your sting? The sting of death is sin, and the power of sin is the law. But thanks be to God! He gives us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ. Therefore, my dear brothers and sisters, stand firm. Let nothing move you. Always give yourselves fully to the work of the Lord, because you know that your labor in the Lord is not in vain” (1 Cor. 15:55–58 NIV).

Douglas Groothuis is author of Christian Apologetics: A Comprehensive Case for Biblical Faith (InterVarsity Press, 2011) and head of the apologetics and ethics M.A. program at Denver Seminary.

NOTES

- Walter Isaacson, Steve Jobs (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2011), 14–15.

- Marlene Winell, Leaving the Fold: A Guide for Former Fundamentalists and Others Leaving Their Religion (Oakland: Harbinger Publications, 1993), 80.

- See Douglas Groothuis, Christian Apologetics: A Comprehensive Case for Biblical Faith (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2011); also J. P. Moreland, Love Your God with All Your Mind, 2nd ed. (1997; Colorado Springs, CO: NavPress, 2012).

- Isaacson, Steve Jobs, 14–15.

- Dwight Goddard, A Buddhist Bible (Boston: Beacon Press, 1938), quoted in Ian S. Markham, A World Religions Reader, 2nd ed. (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 2000), 131.

- See H. P. Owen, “Theism,” in The Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Paul Edwards (New York: Macmillan and the Free Press, 1967) 8:97.

- See Groothuis, Christian Apologetics, chaps. 20–21.

- See Douglas Groothuis, On Jesus (Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 2002), esp. chaps. 4–8.

- See my discussion of this in Christian Apologetics, chap. 25.

- Isaacson, 262.

- See Craig L. Blomberg, “Jesus of Nazareth: How Historians Can Know Him and Why It Matters,” in Groothuis, Christian Apologetics, chap. 19.

- Blaise Pascal, Pensees, rev. ed., ed. Alban Krailsheimer (New York: Penguin, 1966), 121.

- See Groothuis, Christian Apologetics, chaps. 9–17.