This article first appeared in the Christian Research Journal, volume 30, number 01 (2007). For further information or to subscribe to the Christian Research Journal please click here.

SYNOPSIS

Acts 17 is the premiere New Testament model of a Christian apologetic encounter with a pagan culture. Every school of apologetics claims this chapter as its own. Rational argumentation may have been an aspect of Paul’s interaction with the Greek philosophers of Athens at the Areopagus (Greek: the ”Hill of Ares,” also known as Mars’ Hill) that day, but there is another ancient Jewish cultural aspect of Paul’s discourse that often is overlooked. He was not merely accommodating Christianity in rational philosophical terms; he was subverting the Stoic narrative with Judeo‐Christian storytelling.

Subversion is the strategy of engaging oneself in an opponent’s story, retelling the story through a new paradigm and, in the end, taking the opponent’s story captive. An analysis of Paul’s preaching on the Areopagus reveals deliberate similarities to the Stoic narrative that go beyond shallow reference to mere popular culture. The apostle’s oration structurally reflects specific Stoic narrative. Paul subverts Stoicism by retelling the Stoic story through a Christian worldview, thereby leading it captive to the gospel.

Areopagus in Athens. The Areopagus (from the Greek Areios pagos, meaning “Hill of Ares”) was named after the Greek god Ares; when the Roman god Mars was linked with Ares, the spot also became known as Mars’ Hill.1 Athens, especially this hill, was the primary location where the Greek and Roman poets, the cultural leaders of the ancient world, met to exchange ideas (v. 21). The poets would espouse philosophy through didactical tracts, oration, and poems and plays for the populace, just as the popular artists of today propagate pagan worldviews through music, television, and feature films.

Paul’s Areopagus discourse has been used to justify opposing theories of apologetics by Christian cross‐ cultural evangelists, theologians, and apologists alike. It has been interpreted as being a Hellenistic (i.e., culturally Greek) sermon (Martin Dibelius) as well as being entirely antithetical to Hellenism (Cornelius Van Til, F. F. Bruce). Dibelius concludes, “The point at issue is whether it is the Old Testament view of history or the philosophical—particularly the Stoic—view of the world that prevails in the speech on the Areopagus. The difference of opinion that we find among the commentators seems to offer little prospect of a definite solution.”2

One thing most differing viewpoints have in common is their emphasis on Paul’s discourse as rational debate or empirical proof. What they all seem to miss is the narrative structure of his presentation. Perhaps it is this narrative structure that contains the solution to Dibelius’ dilemma. An examination of that structure reveals that Paul does not so much engage in dialectic as he does retell the pagan story within a Christian framework.

First, our examination must put Paul’s presentation in context. He is brought to the Areopagus, which was not merely the name of a location, but also the name of the administrative and judicial body that met there, the highest court in Athens. The Areopagus formally examined and charged violators of the Roman law against “illicit” new religions.3 Though the context suggests an open public interaction and not a formal trial, Luke, the narrator, attempts to cast Paul in Athenian narrative metaphor to Socrates, someone with whom the Athenians would be both familiar and uncomfortable. It was Socrates who Xenophon said was condemned and executed for being “guilty of rejecting the gods acknowledged by the state and of bringing in new divinities.”4 Luke uses a similar phrase to describe Paul when he conveys the accusation from some of the philosophers against Paul in verse 18: “He seems to be a proclaimer of strange deities.”5 Luke depicts Paul from the start as a heroically defiant Socrates, a philosopher of truth against the mob.

EXPLORING PAUL’S STORY

Paul’s sermon clearly contains biblical truths that are found in both Old and New Testaments: God as transcendent creator and sustainer, His providential control of reality, Christ’s resurrection, and the final judgment. It is highly significant to note, however, that throughout the entire discourse Paul did not quote a single Scripture to these unbelievers. Paul certainly was not ashamed of the gospel and regularly quoted Scriptural references when he considered it appropriate (Acts 17:13; 21:17‐21; 23:5; 26:22‐23; 28:23‐28); therefore, his avoidance of Scripture in this instance is instructive of how to preach and defend the gospel to pagans. Quoting chapter and verse may work with those who are already disposed toward God or the Bible, but Paul appears to consider it inappropriate to do so with those who are hostile or opposed to the faith. Witherington adds, “Arguments are only persuasive if they work within the plausibility structure existing in the minds of the hearers.”6 Paul, rather than offending his hearers, addresses them using the narrative structure of Stoic philosophy.

Stoicism and Structure

Missions scholars Robert Gallagher and Paul Hertig explain that the facts of Paul’s speech mimic the major points of Stoic beliefs. They quote the ancient Roman academic Cicero who outlines these Stoic beliefs: “First, they prove that gods exist; next they explain their nature; then they show that the world is governed by them; and lastly that they care for the fortunes of mankind.”7 The correspondence of these themes with what Paul has to say about God shows that he approaches this topic in the standard way that would have been expected by his audience. He thus establishes his credibility as one who should claim their attention.

Paul enters into the discourse of his listeners; he plays according to the rules of the community he is trying to reach. An examination of each point he makes in his oration will reveal that the identification he is making with their culture is not merely with their structural procedures of argument, but with the content of the Stoic worldview. He is retelling the Stoic story through a Christian metanarrative.8

Verse 22

“Men of Athens, I observe that you are very religious in all respects.”

Paul begins his address with the Athenian rhetorical convention, “Men of Athens,” noted by such luminary Greeks as Aristotle and Demosthenes.9 He then affirms their religiosity, which also had been acknowledged by the famous Athenian dramatist Sophocles: “Athens is held of states, the most devout”; and the Greek geographer Pausanias: “Athenians more than others venerate the gods.”10

Verse 23

“I also found an altar with this inscription, ‘TO AN UNKNOWN GOD.’ Therefore what you worship in ignorance, this I proclaim to you.”

This “Unknown God” inscription may have been the Athenian attempt to hedge their bets against any god they may have missed paying homage to out of ignorance.11 Paul quoted the ambiguous text as a point of departure for reflections on true worship, which was the same conventional technique Pseudo‐ Heraclitus used in his Fourth Epistle.12

Verse 24

“The God who made the world and all things in it, since He is Lord of heaven and earth, does not dwell in temples made with hands”

The Greeks had many sacred temples throughout the ancient world as houses for their gods. The Stoics and other cultural critics, however, considered such attempts at housing the transcendent incorporeal nature of deity to be laughable. Zeno, the founder of Stoicism, was known to have taught that “temples are not to be built to the gods.”13 Euripides, the celebrated Athenian tragedian, foreshadowed Paul’s own words with the rhetorical question, “What house fashioned by builders could contain the divine form within enclosed walls?”14 The Hebrew tradition also carried such repudiation of a physical dwelling place for God (1 Kings 8:27) but the context of Paul’s speech rings particularly sympathetic to the Stoics residing in the midst of the sacred hill of the Athenian Acropolis, populated by a multitude of temples such as the Parthenon, the Erechtheion, the Temple of Nike, and the Athenia Polias.

Verse 25

“nor is He served by human hands, as though He needed anything, since He Himself gives to all people life and breath and all things”

The idea that God does not need humankind, but that humankind needs God as its creator and sustainer is common enough in Hebrew thought (Ps. 50:9‐12), but as Dibelius points out:

The use of the word “serve” is, however, almost unknown in the Greek translation of the Bible, but quite familiar in original Greek (pagan) texts, and in the context with which we are acquainted. The deity is too great to need my “service,” we read in the famous chapter of Xenophon’s Memorabilia, which contains the teleological proof of God.15

Seneca wrote, “God seeks no servants; He himself serves mankind,” which is also reflected in Euripides’ claim that “God has need of nothing.”16 Paul is striking a familiar chord with the Athenian and Stoic narratives.

Verse 26a

“and He made from one every nation of mankind,”

Cicero noted that the “universal brotherhood of mankind”17 was a common theme in Stoicism—although when Stoics spoke of “man” they tended to exclude the barbarians surrounding them.18 Nevertheless, as Seneca observed, “Nature produced us related to one another, since she created us from the same source and to the same end.”19

What is striking in Paul’s dialogue is that he neglects to mention Adam as the “one” from which we are created, something he readily did when writing to the Romans (Rom. 5:12‐21). The Athenians would certainly not be thinking of the Hebrew Adam when they heard that reference to “one.” The “one” they would be thinking of would be the gods themselves. Seneca wrote, “All persons, if they are traced back to their origins, are descendants of the gods,” and Dio Chrysostom affirmed, “It is from the gods that the race of men is sprung.”20 Paul may have been deliberately ambiguous by not distinguishing his definition of “one” from theirs, in order to maintain consistency with the Stoic Greek narrative without revealing his hand. He is undermining Stoicism with the Christian worldview, which will be confirmed conclusively in a climactic plot twist at the end of his narrative.

Verse 26b

“to live on all the face of the earth, having determined their appointed times [seasons] and the boundaries of their habitation,”

Christians may read this and immediately consider it an expression of God’s providential sovereignty over history, as in Genesis 1, where God determines the times and seasons, or in Deuteronomy 32:8 where He separates the sons of men and establishes their “boundaries.” Paul’s Athenian audience, however, would refer to their own intellectual heritage on hearing these words. As Juhana Torkki points out, “The idea of God’s kinship to humans is unique in the New Testament writings but common in Stoicism. The Stoic [philosopher] Epictetus devoted a whole essay to the subject.”21 Epictetus writes, “How else could things happen so regularly, by God’s command as it were? When he tells plants to bloom, they bloom, when he tells them to bear fruit, they bear it…Is God [Zeus] then, not capable of overseeing everything and being present with everything and maintaining a certain distribution with everything?”22

Cicero, in one of his Tusculan Disputations, writes that seasons and zones of habitation are evidence of God’s existence.23 Paul continues, with every sentence Luke narrates, to engage Stoic thought by retelling its narrative.

Verse 27

“that they would seek God, if perhaps they might grope for Him and find Him, though He is not far from each one of us;”

This image, as one commentator explains, “carries the sense of ‘a blind person or the fumbling of a person in the darkness of night,’” as can be found in the writings of Aristophanes and Plato.24 Christian apologist Greg Bahnsen suggests that it may even be a Homeric literary allusion to the Cyclops blindly groping for Odysseus and his men.25 In any case, the image is not a positive one. F. F. Bruce affirms the Hellenistic affinities of this section by quoting the Stoic Dio Chrysostom, “primaeval men are described as ‘not settled separately by themselves far away from the divine being or outside him, but…sharing his nature.’”26 Seneca, true to Stoic form, wrote, “God is near you, He is with you, He is within you.”27

This idea of humanity blindly groping around for what is, in fact, very near it is also a part of scriptural themes (Deut. 28:29), but with a distinct difference. To the Stoics, God’s nearness was a pantheistic nearness. They believed everything was a part of God and God was a part of everything, something Paul would vehemently deny (Rom. 1) but, interestingly enough, does not at this point. He is still maintaining a surface connection with the Stoics by affirming the immanence of God without explicitly qualifying it.

Verse 28

“for in Him we live and move and exist, as even some of your own poets have said, ‘For we also are His offspring.’”

Paul thus far implicitly has followed the Stoic narrative without qualifying the differences between it and his full narrative. He now, however, becomes more explicit in identifying with these pagans. He favorably quotes some of their own poets to affirm even more identity with them. “In Him we live and move and exist” is a line from Epimenides’s well‐known Cretica:

They fashioned a tomb for thee, ‘O holy and high one’

But thou art not dead; ‘thou livest and abidest for ever’,

For in thee we live and move and have our being (emphasis added).28

The second line that Paul quotes, “we also are His offspring,” is from

Epimenides’s fellow‐countryman, Aratus, in his Phaenomena:

Let us begin with Zeus, Never, O men, let us leave him

Unmentioned. All the ways are full of Zeus,

And all the market‐places of human beings. The sea is full

Of him; so are the harbors. In every way we have all to do with Zeus,

For we are truly his offspring (emphasis added).29

Aratus was most likely rephrasing Cleanthe’s poem Hymn to Zeus, which not only refers to men as God’s children, but to Zeus as the sovereign controller of all—in whom men live and move

Almighty Zeus, nature’s first Cause, governing all things by law.

It is the right of mortals to address thee,

For we who live and creep upon the earth are all thy children (emphasis added).30

These are the same elements of Paul’s discourse in Acts 17:24‐29.

The Stoics themselves had redefined Zeus to be the impersonal pantheistic force, also called the “logos,” as opposed to a personal deity in the pantheon of Greek gods. This logos was still not anything like the personal God of the Hebrew Scriptures. What is disturbing about this section is that Paul does not qualify the pagan quotations that originally were directed to Zeus. He doesn’t clarify by explaining that Zeus is not the God he is talking about. He simply quotes these hymns of praise to Zeus as if they are in agreement with the Christian gospel. The question arises, why does he not distinguish his gospel narrative from theirs?

The answer is found in the idea of subversion. Paul is subverting their concept of God by using common terms with a different definition that he does not reveal immediately, but that eventually undermines their entire narrative. He begins with their conventional understanding of God but steers them eventually to his own.

In quoting pagan references to Zeus, Paul was not affirming paganism but was referencing pagan imagery, poems, and plays to make a point of connection with them as fellow humans. The imago dei (image of God) in pagans reflects distorted truth, but a kind of truth nonetheless. Paul then recasts and transforms that connection with pagan immanence in support of Christian immanence through the doctrine of transcendence (17:24, 27), the resurrection, and final judgment (17:30‐31), but he saves that twist for the end of his sermon.

Verse 29

“we ought not to think that the Divine Nature is like gold or silver or stone, an image formed by the art and thought of man.”

Another belief of Stoicism was that the divine nature that permeated all things was not reducible to mere artifacts of humanity’s creation. As Epictetus argued, “You are a ‘fragment of God’; you have within you a part of Him…Do you suppose that I am speaking of some external God, made of silver or gold? It is within yourself that you bear Him.”31 Zeno taught, “Men shall neither build temples nor make idols.” Dio Chrysostom wrote, “The living can only be represented by something that is living.”32 Once again, Paul is not ignoring the biblical mocking of “idols of silver and gold” as in Psalm 115:4, but is certainly addressing the issue in a language his hearers would understand, the language of the Stoic narrative.

Verse 30

“Therefore having overlooked the times of ignorance,”

For the Stoics, ignorance was an important doctrine. It represented the loss of knowledge that humanity formerly possessed, knowledge of their pantheistic unity with the logos. Dio Chrysostom asks in his Discourses, “How, then, could they have remained ignorant and conceived no inkling…[that] they were filled with the divine nature?”33 Epictetus echoes the same sentiment in one of his Discourses, which is quoted in part above: “You are a ‘fragment of God’; you have within you a part of Him. Why then are you ignorant of your own kinship?34 “Pauline “ignorance” was a willing, responsible ignorance, a hardness of heart that came from sinful violation of God’s commands (Eph. 4:17‐19)—but, yet again, Paul does not articulate this distinction. He instead makes an ambiguous reference to a generic “ignorance” that the Stoics most naturally would interpret in their own terms. As Talbert describes, “In all of this, he has sought the common ground. There is nothing he has said yet that would appear ridiculous to his philosophic audience.”35

Verses 30‐31

“God is now declaring to men that all people everywhere should repent, because He has fixed a day in which He will judge the world in righteousness through a Man whom He has appointed, having furnished proof to all men by raising Him from the dead.”

Here is where the subversion of Paul’s storytelling rears its head, like the mind‐blowing twist of a movie thriller. Everything is not as it seems. Paul the storyteller gets his pagan audience to nod their heads in agreement, only to be thrown for a loop at the end. Repentance, judgment, and the resurrection, all antithetical to Stoic beliefs, form the conclusion of Paul’s narrative.

Witherington concludes of this Areopagus speech, “What has happened is that Greek notions have been taken up and given new meaning by placing them in a Jewish‐Christian monotheistic context. Apologetics by means of defense and attack is being done, using Greek thought to make monotheistic points. The call for repentance at the end shows where the argument has been going all along—it is not an exercise in diplomacy or compromise but ultimately a call for conversion.”36

The Stoics believed in a “great conflagration” of fire where the universe would end in the same kind of fire out of which it was created.37 This was not the fire of damnation, however, as in Christian doctrine. It was rather the cyclical recurrence of what scientific theorists today would call the “oscillating universe.” Everything would collapse into fire, and then be recreated again out of that fire and relive the same cycle and development of history over and over again. Paul’s call of final, linear, once‐for‐all judgment by a single man was certainly one of the factors, then, that caused some of these interested philosophers to scorn him (v. 32). Note again, however, that even here, Paul never gives the name of Jesus. He alludes to Him and implies His identity, which seems to maintain a sense of mystery about the narrative (something many modern evangelists would surely criticize) . Did everyone know that he was talking about Jesus? At times, silence can be louder than words, and implication can be more alluring than explication.

The other factor sure to provoke the ire of the cosmopolitan Athenian culture‐shapers was the proclamation of the resurrection of Jesus. The poet and dramatist Aeschylus wrote what became a prominent Stoic slogan: “When the dust has soaked up a man’s blood, once he is dead there is no resurrection.”38 Paul’s explicit reference to the resurrection was certainly a part of the twist he used in his subversive storytelling to get the Athenians to listen to what they otherwise might ignore.

Secular Sources

A couple of important observations are in line regarding Paul’s reference to pagan poetry and non‐ Christian mythology. First, it points out that, as an orthodox Pharisee who stressed the separation of holiness, he did not consider it unholy to expose himself to the godless media and art forms (books, plays, and poetry) of his day. He did not merely familiarize himself with them, he studied them—well enough to be able to quote them and even utilize their narrative. Paul primarily quoted Scripture in his writings, but he also quoted sinners favorably when appropriate.

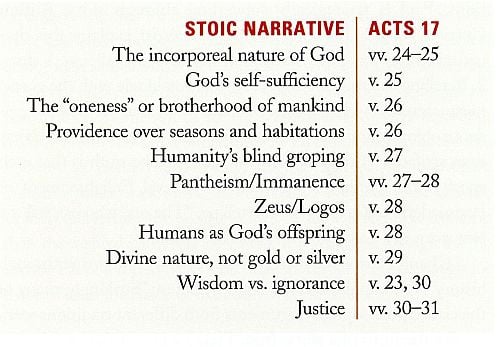

Second, this appropriation of pagan cultural images and thought forms by biblical writers reflects more than a mere quoting of popular sayings or shallow cultural reference. It illustrates a redemptive interaction with those thought forms, a certain amount of involvement in, and affirmation of, the prevailing culture, in service to the gospel. A simple comparison of Paul’s sermon in Acts 17 with Cleanthes’s Hymn to Zeus, a well‐known summary of Stoic doctrine, illustrates an almost point‐by‐point correspondence of ideas.39 Paul’s preaching in Acts 17 is not a shallow usage of mere phrases, but a deep structural identification with Stoic narrative and images that “align with” the gospel. The list of convergences can be summarized thus:

Lastly, this incident is not the only place where subversion occurs in the Bible. The Dictionary of New Testament Background cites more than 100 New Testament passages that reflect “Examples of Convergence between Pagan and Early Christian Texts.” Citations, images and word pictures are quoted, adapted, or appropriated from such pagans as Aeschylus, Sophocles, Plutarch, Tacitus, Xenophon, Aristotle, Seneca, and other Hellenistic cultural sources. The sheer volume of such biblical reference suggests an interactive intercourse of Scriptural writings with culture rather than absolute separation or shallow manipulation of that culture.40

SUBVERSION VS. SYNCRETISM

Some Christians may react with fear that this kind of redemptive interaction with culture is syncretism, an attempt to fuse two incompatible systems of thought. Subversion, however, is not syncretism. Subversion is what Paul engaged in.

In subversion, the narrative, images, and symbols of one system are discreetly redefined or altered in the new system. Paul quotes a poem to Zeus, but covertly intends a different deity. He superficially affirms the immanence of the Stoic “Universal Reason” that controls and determines all nature and men, yet he describes this universal all‐powerful deity as personal rather than as abstract law. He agrees with the Stoics that men are ignorant of God and His justice, but then affirms that God proved that He will judge the world through Christ by raising Christ from the dead—two doctrines the Stoics were vehemently against. He affirms the unity of humanity and the immanence of God in all things, but contradicts Stoic pantheism and redefines that immanence by affirming God’s transcendence and the Creator/creature distinction. Paul did not reveal these stark differences between the gospel and the Stoic narrative until the end of his talk. He was subverting paganism, not syncretizing Christianity with it.

Subversive Story Strategy

By casting his presentation of the gospel in terms that Stoics could identify with and by undermining their narrative with alterations, Paul is strategically subverting through story. Author Curtis Chang, in his book Engaging Unbelief, explains this rhetorical strategy as three‐fold: “1. Entering the challenger’s story, 2. Retelling the story, 3. Capturing that retold tale with the gospel metanarrative.”41 He explains that the claim that we observe evidence objectively and apply reason neutrally to prove our worldview is an artifact of Enlightenment mythology. The truth is that each epoch of thought in history, whether Medieval, Enlightenment, or Postmodern, is a contest in storytelling. “The one who can tell the best story, in a very real sense, wins the epoch.”42

Chang affirms the inescapability of story and image through history even in philosophical argumentation: “Strikingly, many of the classic philosophical arguments from different traditions seem to take the form of a story: from Plato’s scene of the man bound to the chair in the cave to Hobbes’s elaborate drama of the ‘state of nature,’ to John Rawls’s ‘choosing game.’”43 Stories may come in many different genres, but we cannot escape them.

Many Christian apologists and theologians have tended to focus on the doctrinal content of Paul’s Areopagus speech at the expense of the narrative structure that carries the message. There is certainly more proclamation in this passage than rational argument.

The progression of events from creation to fall to redemption that characterize Paul’s narrative reflects the beginning, middle, and end of linear Western storytelling. God is Lord, He created all things and created all people from one (creation), then determined the seasons and boundaries. People then became blind and were found groping in the darkness post‐Eden, ignorant of their very identity as His children (fall). Then God raised a man from the dead and will judge the world in the future through that same man. Through repentance, people can escape their ignorance and separation from God (redemption). Creation, fall, redemption; beginning, middle, end; Genesis, Covenant, Eschaton are elements of narrative that communicate worldview.

Does this retelling of stories simply reduce persuasion to a relativistic “stand‐off” between opposing stories with no criteria for discerning which is true? Scholar N. T. Wright suggests that the way to handle the clash of competing stories is to tell yet another story, one that encompasses and explains the stories of one’s opposition, yet contains an explanation for the anomalies or contradictions within those stories:

There is no such thing as “neutral” or “objective” proof; only the claim that the story we are now telling about the world as a whole makes more sense, in its outline and detail, than other potential or actual stories that may be on offer. Simplicity of outline, elegance in handling the details within it, the inclusion of all the parts of the story, and the ability of the story to make sense beyond its immediate subject‐matter: these are what count.44

While a significant number of Christian apologists would consider Wright’s claim as neglectful of Paul’s appeal to evidence elsewhere (v. 31), it is certainly instructive of the opposite neglect that many have had for the legitimate operations of story or narrative coherence in persuasion.

Paul tells the story of mankind in Acts 17, a story that encompasses and includes images and elements of the Stoic story, but solves the problems of that system within a more coherent and meaningful story that conveys Christianity. He studies and engages in the Stoic story, retells that story, and captures it with the gospel metanarrative. Paul subverts Stoic paganism with the Christian worldview.

Samplings of Subversion

In the first paragraph of this article, I mentioned the entertainment of Hollywood as a strong analogy of the influence of the Greek poets. I would like to conclude with an example of a Hollywood movie that uses subversive storytelling in a way similar to Paul on the Areopagus. The Exorcism of Emily Rose, written and directed by Scott Derrickson, uses the power of story to subvert the modernist mindset that believes all spiritual beliefs are superstitious misunderstandings of scientific phenomena. Emily Rose is based on an allegedly true story of a Roman Catholic priest on trial for criminal negligence in the death of a college girl named Emily Rose. Emily comes to the priest because she believes she is demon possessed. In the midst of a laborious exorcism ritual, she dies from self‐inflicted wounds, and the priest goes to trial. The setting of a court is strikingly reminiscent of Paul’s standing in the Areopagus, speaking to the “modernist” lawyers and rhetoricians of his day.

Erin Bruner, a female attorney, defends the priest by seeking to prove the “possibility” of demon possession in court. The prosecutor mocks her through the trial, referring to her spiritual arguments as superstition unworthy of legal procedure in a modern scientific world. He then seeks to prove that Emily had epilepsy, which required drugs, not “voodoo,” resulting in the priest’s blood guilt. The movie presents both sides of the argument in court so equally that legal or rational certainty is impossible. The privilege of seeing Emily’s experience of demon possession outside that court of law leaves the viewer with a strong sense that the empirical prejudice of modern science has been undermined. Supernatural evil, and by extension, supernatural good (God) is real. Derrickson uses the story to subvert the stranglehold of modernity on the Western mind, and the inadequacy of rationalism and the scientific method in discovering everything there is to know about truth.

Other examples of subversion in Hollywood movies are: The Island, which uses a science‐fiction action chase film to subvert the utilitarian murderous ethos of our “pro‐choice” culture; The Wicker Man, a subversion of Wicca and pagan earth worship; and Apocalypto, a subversion of the “noble savage” myth of the indigenous native Americans.

The traditional approach to Christian apologetics is the detailed accumulation of rational arguments and empirical evidence for the existence of God, the reliability of the Bible, and the miraculous resurrection of Jesus Christ. The conventional image of a Christian apologist is one who studies apologetics or philosophy at a university, one who wields logical arguments for the existence of God and manuscript evidence for the reliability of the Bible, or one who engages in debates about evolution or Islam. These remain valid and important endeavors, but in a postmodern world focused on narrative discourse we need also to take a lesson from the apostle Paul and expand our avenues for evangelism and defending the faith. We need more Christian apologists writing revisionist biographies of godless deities such as Darwin, Marx, and Freud; writing for and subverting pagan television sitcoms; bringing a Christian worldview interpretation to their journalism in secular magazines and news reporting; making horror films that undermine the idol of modernity as did The Exorcism of Emily Rose; writing, singing, and playing subversive industrial music, rock music, and rap music. We need to be actively, sacredly subverting the secular stories of the culture, and restoring their fragmented narratives for Christ. If it was good enough for the apostle Paul on top of Mars’ Hill then, it’s certainly good enough for those of us in the shade of the Hollywood hills now.45

Brian Godawa is the screenwriter for the award-winning feature film, To End All Wars. He is author of Hollywood Worldviews: Watching Films with Wisdom and Discernment (InterVarsity Press, 2002).

NOTES

- See Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, s.v. “Areopagus,” the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., http://en.wikipedia.org/ wiki/Areopagus. See also The Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001–05), s.v. “Mars, in Roman Religion and Mythology,” and “Mars’ Hill,” http://www.bartleby.com/65/ma/Mars‐html, and http://www.bartleby.com/65/ma/MarsHill.html.

- Martin Dibelius and K. C. Hanson, The Book of Acts: Form, Style, and Theology (Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress Publishers, 2004), 98.

- Robert L. Gallagher and Paul Hertig, Mission in Acts: Ancient Narratives in Contemporary Context (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2004), 224–25.

- Xenophon, Memorabilia, chap. 1. See also Plato, Apology 24B‐C; Euthyphro 1C; 2B; 3B.

- All Scripture quotations are from the New American Standard Bible.

- Ben Witherington III, The Acts of the Apostles: A Socio‐Rhetorical Commentary (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998), 530.

- Cicero, On The Nature of the Gods4, quoted in Gallagher and Hertig, 230.

- Although the text reveals that both Epicureans and Stoics were there (Acts 17:17–18), it appears that Paul chooses Stoicism to identify with, perhaps because of its closer affinity with the elements of his intended message.

- Aristotle, Or. 1, Demosthenes, Exordia 54, quoted in Witherington, 520.

- Sophocles, Oedipus Tyrannus, 260; Pausanias, Description of Greece, 1.17.1, quoted in Charles H. Talbert, Reading Acts: A Literary and Theological Commentary on the Acts of the Apostles (Macon, GA: Smyth and Helwys Publishing, 2001), 153.

- Dibelius and Hanson, 103.

- Talbert, 153.

- Explained of Zeno by Plutarch in his Moralia, 1034B, quoted in Juhana Torkki, “The Dramatic Account of Paul’s Encounter with Philosophy: An Analysis of Acts 17:16–34 with Regard to Contemporary Philosophical Debates” (academic dissertation, Helsinki: Helsinki University Printing House, 2004), 105.

- Euripides, frag. 968, quoted in F. F. Bruce, Paul, Apostle of the Heart Set Free (Cumbria, UK: Paternoster Press Ltd., 2000), 240.

- Dibelius and Hanson, 105‐

- Seneca, Epistle47; Euripides, Hercules 1345–46, quoted in Talbert, 155.

- Cicero, On Duties, 3.6.28, quoted in Lee, 88.

- Bruce, 241.

- Seneca, Epistle52, quoted in Michelle V. Lee, Paul, the Stoics, and the Body of Christ (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 84.

- Seneca, Epistle1; Dio Chrysostom, Oration 30.26, quoted in Talbert, 156.

- Torkki, 87.

- Epictetus Discourse14, quoted in A. A. Long, Epictetus: A Stoic and Socratic Guide to Life (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2002), 25–26.

- Cicero Tusculan Disputations28.68–69, quoted in Talbert, 156.

- Aristophanes Ec. 315, Pax 691; Plato Phaedo 99b, quoted in Witherington, 528–29.

- Greg Bahnsen, Always Ready: Directions for Defending the Faith, ed. Robert Booth (Atlanta: American Vision, 1996), 260–61.

- Dio Chrysostom Olympic Oration 12:28, quoted in F. F. Bruce, The Book of the Acts, New International Commentary on the New Testament, rev. ed. (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1988), 339.

- Seneca Epistle1–2, quoted in Talbert, 156.

- Bruce, The Book of the Acts 338–39.

- Ibid.

- Loring Brace, Unknown God or Inspiration Among Pre‐Christian Races (1890; repr., Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing, 2003), 123.

- Epictetus, Discourses8.11–12, quoted in Gallagher, 232.

- Clement of Alexandria, Miscellanies76; Dio Chrysostom, Oration 12.83, quoted in Talbert, 156.

- Dio Chrysostom, Discourses27; cf. 12.12, 16, 21, quoted in Gallagher, 229.

- Epictetus, Discourses8.11–14, quoted in Gallagher, 229.

- Talbert, 156.

- Witherington, 524.

- Ibid., 526.

- Aeschylus, Eumenides 647, quoted in Bruce, Paul, Apostle of the Heart Set Free, 247.

- See Cleanthes, “Hymn to Zeus” (trans. M. A. C. Ellery, 1976), Department of Classics, Monmouth College, http://www.utexas.edu/courses/citylife/readings/cleanthes_hymn.html.

- D. Charles, “Examples of Convergence between Pagan and Early Christian Texts,” The Dictionary of New Testament Background (InterVarsity Christian Fellowship/USA, 2000). Electronic text hypertexted and prepared by OakTree Software, Inc. Version 1.0.

- Curtis Chang, Engaging Unbelief: A Captivating Strategy from Augustine to Aquinas (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2000), 26.

- Ibid., 29.

- Ibid.,30.

- N.T. Wright, The New Testament and the People of God (Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress Press, 1992), 42.

- This article is excerpted and adapted from a manuscript the author plans to have published, tentatively titled, Word Pictures: Knowing God Through Story and Imagination.