This article was published exclusively online in the Christian Research Journal, Volume 47, number 01 (2024).

When you support the Journal, you join the team and help provide the resources at equip.org that minister to people worldwide. These resources include our ever-growing database of more than 2,000 articles, as well as our free Postmodern Realities podcast.

Another way you can support our online articles is by leaving us a tip. A tip is just a small amount, like $3, $5, or $10, which is the cost of a latte, lunch out, or coffee drink. To leave a tip, click here.

[Editor’s Note: This review contains spoilers for Lessons in Chemistry.]

Book Review

Bonnie Garmus

Lessons in Chemistry

Doubleday, 2022

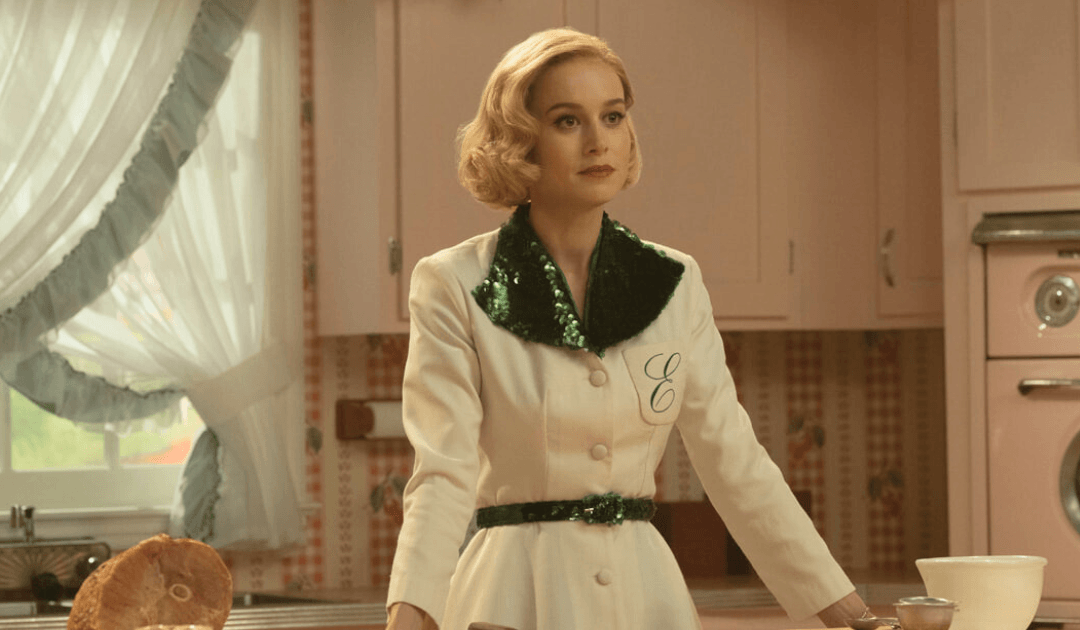

Television Series Review

Lessons in Chemistry

Developed by Lee Eisenberg

Starring Brie Larson, Lewis Pullman, Aja Naomi King, Stephanie Koenig

Apple TV+ (October 2023, Eight Episodes)

Rated TV–MA

“I have decided that it was smart to write when I was so angry,” she says. “If I hadn’t had that awful meeting that day, maybe I wouldn’t have written another book.”1

Bonnie Garmus had a really bad day. Granted, I’ve had similar bad days — those days where you have this phenomenal idea and nobody responds until someone else says the idea, and then everyone gets excited and pats them on the back for being so brilliant. Welcome to my entire 9th grade year on the cheerleading squad.

In Garmus’s case, it was a group of men who seemed to hear good ideas from only other men. And I get it; it happens, and it’s frustrating. But as I alluded to previously, this isn’t just a male/female problem. It can happen anywhere, with anyone. But isn’t it so much easier to shove everything into the already-accepted boxes of oppression?2 Garmus has a whole mess of agendas, and she makes them loud and clear in her 2022 international bestselling novel, Lessons in Chemistry.3 Not least, “Damn the patriarchy!” (especially the one from 70 years ago). As one reviewer stated, “Elizabeth [the main character] was difficult to warm to — not because of her abrasive personality — because she felt like a mouthpiece for 21st Century feminist monologues. This is supposed to be the 1950s? I just didn’t buy it. All her rants are straight out of a modern-day Smash the Patriarchy podcast.”4

Lessons in Tropes

“And once you find one,” she said, “maybe a lawyer,” she specified, “then you can stop all this science nonsense and go home and have lots of babies.”5

Within the first thirty pages, I started a back-of-the-book list titled “tropes/clichés.” After reading some other book reviews, I discovered that I was not the only person who did this.6 According to Lessons in Chemistry, Elizabeth Zott is a stunningly beautiful third-wave feminist (before third-wave feminism even existed)7 who never wants to marry or have children.8 Elizabeth’s clear hatred of religion in general (and Christianity in particular) stems from her parents, who were traveling, hyper-fundamental, spiritually abusive, doom-and-gloom evangelists who used fake miracles to con people out of their money while never paying taxes. Her brother was, of course, a homosexual who committed suicide after their father told him how much God hated him.

We walk with Elizabeth through a fairly graphic sexual assault and are enraged along with her when the police officer asks if she would like to apologize to the perp for stabbing him with a pencil in order to escape. Her “lack of remorse” leads UCLA to revoke her acceptance to their PhD program, and she is forced to get a job elsewhere. At that job, she is mistaken for the secretary, asked to make coffee by her male peers, and called the “c” word by her boss. Her colleagues will recognize her brilliance only in secret (when they are stumped by their own work), but nobody will openly treat her as an equal; they’ll just put a higher-ranked man’s name on her work and tell her to be grateful that it was published at all. As one reviewer stated, “As a woman who has worked in a STEM field since the 1960s (yes, I still do some research part-time), it feels like the author has learned about every bad thing that ever happened to women in STEM and made ALL of them happen to Elizabeth” (emphasis in original).9

Elizabeth’s love-life is no less trope-y. Straight out of every rom-com, she and the most eligible bachelor (a Nobel Prize-nominated chemist) have a huge misunderstanding, hate each other at first, but then fall head over heels as he discovers the genius hidden behind her “flawless skin.”10 They have lots of sex with no fear of pregnancy (even though birth control will not exist for almost two decades). We learn that he is an orphan twice over. First, his parents die, and then the aunt raising him also dies. This, of course, leaves him to be raised in a sexually and religiously abusive Catholic orphanage. Mind you, all of this occurs in the first forty pages of an almost 400-page book!

Lessons in Chemistry was intended to depict how unfair and condescending men are towards women (especially in the sciences). But it attempts to do so by featuring a supposed chemistry-expert heroine, written by a woman who knows very little about chemistry.11 I’m not a chemist, but I did teach chemistry for several years at the high school level. When I say that Garmus’s “science” dialogue is embarrassing, it’s embarrassing.12 Garmus was clearly trying to drop in as many chemistry references as possible, whether or not they actually make sense for the story. (Thankfully, Apple TV+’s mini-series redeemed Garmus’s Elizabeth Zott character by consulting actual scientists and science writers for the script.)

So, ironically, while Garmus intended to punch back at the patriarchy for not taking women more seriously, all it did was give fodder to the ones claiming that women are not as smart as men. If a misogynist man were to pick up this book, he’d probably put it down, shake his head, and conclude, “There go these women again…thinking they can do science.”

Lessons in Empathy

“I fell in love with Calvin,” she was saying, “because he was intelligent and kind, but also because he was the very first man to take me seriously. Imagine if all men took women seriously.”13

No matter what my personal thoughts are, we must consider the impact of this book. With more than 275,000 reader reviews on Amazon and over a million ratings on Goodreads, I have never seen a book so widely reviewed. Nobody can deny that Lessons in Chemistry has struck a chord. Love it or hate it (and those seem to be the two main responses), a reception of this magnitude should give us pause and make us ask: What issue is this book identifying that would cause hundreds of thousands of women to respond this fanatically?

I cannot accept that the popularity is based on Garmus’s writing prowess. Though she had some well-written moments, I found the characters too unlikable and ill-developed. As noted, the plotline is full of tropes and more than a few massive scientific holes.14 No, the popularity must be explained on the basis of the motifs themselves. In looking over the reviews (or as best I could with the number of reviews out there), I noticed a few recurring themes.

Women Are Tired of Not Being Taken Seriously. Male supremacy and misogyny are major themes in both the reviews and in the book. The main character, Elizabeth, owes the success of her cooking show to the fact that she makes women feel seen, heard, and important. The narrator explains, “There was a lot of talk about acids and bases and hydrogen ions….Throughout the process, Elizabeth, her face serious, told her viewers that they were up for this difficult challenge, that she knew they were capable, resourceful people, and that she believed in them.”15

Elizabeth doesn’t talk down to the housewives. Or, as one fictional Supper at Six fan says, “I like how she uses science-y words….It makes me feel — I don’t know — capable.”16 Not only does Elizabeth make these women feel smart, she makes them feel seen: “It is my experience that far too many people do not appreciate the work and sacrifice that goes into being a wife, a mother, a woman….At the end of our thirty minutes together, we will have done something worth doing. We will have created something that will not go unnoticed. We will have made supper. And it will matter” (emphasis in original).17

I can’t emphasize this enough: If we have hundreds of thousands of women saying “Yes! Thank you for dignifying me!” then we should probably recognize that we, as a society, have failed them in a major way. As Elizabeth says to her producer, “There is nothing average about the average housewife.”18 I’m pretty sure the 600,000+ women on Goodreads who gave the book five stars agree.

Women Are Disappointed in Themselves for Not Doing More. Another theme I noticed in all the book reviews is the almost hero-worship of what Elizabeth represents.19 There was even a real-life reviewer who — like the bit-character Mrs. Fillis (the housewife who decides to become a heart surgeon) — has decided to return to school to study science.20

In many ways, women who have chosen to be housewives and devote their lives to raising children aren’t necessarily saying that they would do it differently. They just wanted to be treated as if they could have, had they chosen to. Which brings me to my next point.

Moms Are Tired of Sacrificing, and Then Being Denigrated for Their Sacrifice. In most societies, sacrificing oneself for the good of others is seen as heroic and noble — that is, until we get to motherhood. Modern-day motherhood bears very little resemblance to motherhood in the past. The reason for that is that modern-day fatherhood has changed just as drastically, thanks to the Industrial Revolution. As Nancy Pearcey writes in The Toxic War on Masculinity, “Because work was conducted in the home, both parents were able to be involved in economically productive work while raising their children. Fathering was not a separate activity that a man came home to after clocking out from work….Colonial women were likewise able to combine economically productive work with childrearing.”21 Pearcey goes on to quote Joan Williams: “If the husband had a trade, his wife often worked with him….We find reports of women as blacksmiths, wrights, printers, tinsmiths, beer makers, tavern keepers, shoemakers, shipwrights, barbers, grocers, butchers, and shopkeepers.”22

Prior to industrialization, women weren’t confined to being alone all day with the children and nothing but cooking, dishes, laundry, and errands to occupy their time. The sad fact is that post-Industrial Revolution, almost all interesting tasks were removed from the home, and then women were told that it was their “place” to stay there. All the gifts and talents that their foremothers once used in partnerships with their forefathers were replaced by the monotony of daily chores — for which there was no monetary increase for the household, and thus held as lower in value. Is it any wonder that motherhood has become so degraded?

And yet we have many women who have willingly stepped into this role for the sake of their children and families — foregoing outside work where they can regularly interact with other adults and use their minds to problem solve and their talents to create. Some women absolutely love their roles as homemaker and mom and feel wonderfully challenged, fulfilled, and able to flourish in their gifts. Others, not so much; it is a sacrifice that they willingly make, but it is a sacrifice nonetheless. Then, to add insult to injury, segments of society treat them like sellouts who just weren’t smart enough for “real work.” Welcome to modern-day motherhood.

Lessons in Apologetics

“Don’t you think it’s possible to believe in both God and science?” “Sure,” Calvin had written back. “It’s called intellectual dishonesty.”23

As with anything that has received this amount of attention, apologists have an excellent opportunity to use both the book and the TV mini-series to enter into conversations of faith. And boy are there opportunities.

Garmus does not hide her disdain for organized religion (or theism for that matter). Her ideal role model, Elizabeth, is unabashedly atheist in a time when atheism was not talked about in polite company. The reasons? Science, lack of evidence, and church abuse. These sentiments are repeated more than a few times throughout the book. Faith is caricatured as blind faith without any reasons. In a conversation with a young Reverend Wakely, Calvin Evans (Elizabeth’s love interest) asks, “Why do you think so many people believe in texts written thousands of years ago? And why does it seem the more supernatural, unprovable, improbable, and ancient the source of these texts, the more people believe them?” To this, Wakely responds, “People need to believe in something bigger than themselves.”24 Unfortunately, there are far too many Christians — even those in leadership — who perpetuate this stereotype. We can (and should) do better.

Lessons in Chemistry almost serves as an apologetics anti-primer, with basic anti-Christian arguments peppered throughout the book’s dialogue. In discussing these themes with others, the apologist has the opportunity to ask those around them, “What did you think about the arguments Garmus’s characters gave against God and Christianity? Do you agree with their statements?” There is ample opportunity to address the existence of God, the relationship between faith and science, the reliability of the Bible, and more.

As far as the TV series is concerned, Reverand Wakely is much more astute, especially when modeling how to interact with a skeptic. He doesn’t treat Calvin or Madeline like projects who need to be convinced. He doesn’t try to get to the bottom of their skepticism in the first conversation. In the series, when Calvin discusses Darwin with Wakely, the Reverand’s first response is, “If there’s one thing that Darwin and I agree on….”25 Looking for common ground should be the apologist’s first instinct before launching into answer mode.

Later, when Reverand Wakely interacts with Madeline Zott (Elizabeth and Calvin’s daughter) he listens to her questions without judgment. Wakely not only tolerates Madeline’s questions but encourages them! This is the kind of open dialogue we should be encouraging. As Fuller Youth Institute states on the back of their Sticky Faith curriculum, “It’s not doubt or hard questions that are toxic to faith. It’s silence.”26 The church should be the first place that people feel safe bringing their questions. And likewise, it would behoove church leaders to have something a bit more substantial than “Just have faith.” While I didn’t agree with everything that Reverand Wakely says, his was a demeanor worth imitating.

All in all, I am glad that I was introduced to this book, if for no other reason than I enjoyed the TV show so much. (But then again, my bar for it was pretty low after reading the book.) Having been surrounded by respectful and loving men for the majority of my life, it is important for me to be reminded that my experiences are not the norm — though they should be. Popular novels are outside of my normal reading regimen, and it is important for us nerds to poke our heads out from our ideological non-fiction occasionally to get a pulse on what is going on in normal society. If we sequester ourselves to the realm of academics, we lose our ability to interact with our neighbors. And isn’t interacting with our neighbors the entire purpose for our study to begin with? On a more positive note, Lessons in Chemistry provides several excellent talking points that can be used by apologists. Classic apologetics has long centered around answering the question, Is it (Christianity) true? Cultural apologetics (especially now in the rioting-twenties) tends to center more on the question, Is it good? —Hillary Morgan Ferrer

Hillary Morgan Ferrer is founder and president of Mama Bear Apologetics and coauthored and edited the bestselling book Mama Bear Apologetics: Empowering Your Kids to Challenge Cultural Lies (Harvest House Publishers, 2019). She has degrees in both film and biology and spends her time as an author, speaker, teacher, and apologist encouraging others to discern culture from a biblical worldview.

NOTES

- Bonnie Garmus, quoted in Lisa Allardice, “‘It Was Smart to Write When I Was So Angry’: Bonnie Garmus on the Winning Formula behind Lessons in Chemistry,” The Guardian, December 16, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/dec/16/it-was-smart-to-write-when-i-was-so-angry-bonnie-garmus-on-the-winning-formula-behind-lessons-in-chemistry.

- See “Matrix of Oppression,” Office of Equity, University of Colorado, Denver, accessed March 11, 2024, https://www1.ucdenver.edu/docs/librariesprovider102/default-document-library/matrix-of-oppression.pdf.

- Bonnie Garmus, Lessons in Chemistry (New York: Doubleday, 2022). On Amazon alone (as of March 12, 2024) the word “agenda” is present in 66 different reviews, with 144–249 mentions of feminism/feminist, 29–67 references to atheism/atheist, 219 mentions of religion bashing of some sort, 67 references to church more specifically, 80 references to Christianity even more specifically, and 84 mentions of Catholicism by name.

- Emily May, Review of Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus, Goodreads, December 20, 2022, https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/58065033-lessons-in-chemistry.

- Garmus, Lessons in Chemistry, 106.

- Sophie Reads Books, “Lessons in Chemistry — Bonnie Garmus | Book Review (I Hated It…),” YouTube, May 26, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8VEovc2rv6k.

- As one reviewer stated, “Elizabeth is a SCIENTIST in the 1950s but reads like someone time traveled back from 2022 just to spout feminist monologues at anyone within earshot!!!” (emphasis in original). Lisa, Review of Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus, Goodreads, May 5, 2022, https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/58065033-lessons-in-chemistry.

- References to babies in this book include “little Satan” (p. 142), “gremlin” (143), “horrible” (145), and “selfish little sadists” (146). Garmus, Lessons in Chemistry.

- Would-be astronaut, “Everything That’s Cliché about Women in STEM,” Review of Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus, Goodreads, October 1, 2023, https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/58065033-lessons-in-chemistry.

- Garmus, Lessons in Chemistry, 3.

- Garmus admitted as such in interviews, saying that she had to “teach [herself] chemistry” to write this book. Sarah McKenna, “Bonnie Garmus Interview: ‘I Had to Teach Myself Chemistry from a 1950s Textbook,’” Penguin Books Limited, March 29, 2024, https://www.penguin.co.uk/articles/2022/03/bonnie-garmus-interview-lessons-in-chemistry.

- Seriously, you don’t have working scientists (especially not a Nobel Prize-nominated scientist) arguing over covalent bonds. And nobody, not even chemists, labels their drinking water as H2O, refers to table salt as sodium chloride, or expects a bunch of housewives to know that CH3COOH is vinegar. And even a gifted scientist could never create an abiogenesis lab in their house. Simply touching an experiment with your hands can denature a protein and render the experiment null. Nobody could keep their open-air kitchen at the necessary temperature for those kinds of experiments. Nor would they drink coffee using their lab equipment.

- Garmus, Lessons in Chemistry, 331.

- See note 12.

- Garmus, Lessons in Chemistry, 235.

- Garmus, Lessons in Chemistry, 255.

- Garmus, Lessons in Chemistry, 217.

- 1Garmus, Lessons in Chemistry, 202.

- “Elizabeth is no ordinary woman, she refuses to pander to fragile male egos, it worries her not one whit that she doesn’t fit in at the patriarchal Hastings Institute, she accepts no limitations for herself, nor for anyone else.” Paromjit, Review of Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus, Goodreads, March 10, 2022, https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/58065033-lessons-in-chemistry.

- “And at the ripe old age of 61, I decided to go back to school. To study the science that has long beckoned to me.” Lisa Holliday Lee, Review of Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus, Amazon.com, July 2, 2022, https://www.amazon.com/Lessons-Chemistry-Novel-Bonnie-Garmus/dp/038554734X.

- Nancy R. Pearcey, The Toxic War on Masculinity (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 2023), 73–74.

- Joan C. Williams, Unbending Gender: Why Family and Work Conflict and What to Do About it (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 21.

- Garmus, Lessons in Chemistry, 193.

- Garmus, Lessons in Chemistry, 194.

- Lessons in Chemistry, season one, episode seven, “Book of Calvin,” directed by Tara Miele, written by Bonnie Garmus, Lee Eisenberg, Elissa Karasik, aired November 17, 2023, on Apple TV+ (https://tv.apple.com/us/episode/book-of-calvin/umc.cmc.4lkrs91s1sttj27kiz55ppjp).

- Jim Candy, Brad M. Griffin, and Kara Eckmann Powell, Can I Ask That?: 8 Hard Questions About God and Faith: A Sticky Faith Curriculum (Pasadena, CA: Fuller Youth Institute, 2014), back cover.