Listen to this article (17:13 min)

Theological Trends Column

This article was published exclusively online in the Christian Research Journal, Volume 48, number 02 (2025).

When you support the Journal, you join the team and help provide the resources at equip.org that minister to people worldwide. These resources include our ever-growing database of more than 2,500 articles and Bible Answers, as well as our free Postmodern Realities podcast.

Another way you can support our online articles is by leaving us a tip. A tip is just a small amount, like $3, $5, or $10, which is the cost of a latte, lunch out, or coffee drink. To leave a tip, click here.

A few years ago, a hilarious video made the rounds on social media of a married couple sitting together on their living room sofa. The woman is overwrought and anxious. “There’s all this pressure, you know?” she says, “And sometimes it feels like it’s right up on me.” The camera shifts and the viewer discovers that she has a nail sticking out of her forehead. Her husband, exasperated, says, “Yeah, well, you do have a nail in your head.” “Stop trying to fix it!” she cries, “You always do this, you always try to fix things.” Her husband sighs heavily and tries to pay attention while she complains that all of her sweaters are snagged — “like, all of them” — and that she can’t get enough sleep. “That sounds really hard,” he finally says, but when he leans in to kiss her, he gets whacked with the nail. The scene ends with the funny, and obvious, conclusion, “It’s not about the nail.”1

Over the many years as I’ve attempted to listen to the complaints of progressive and deconstructing Christians and Ex-vangelicals, I have gradually come to feel like the sane though exasperated husband in “It’s Not About the Nail” — the person standing by, helpless, replete with pertinent information about God and the Bible that won’t end up being of any use because the distressed person is not interested in solutions and answers, but only the bleak experience of living in a sin-sick world. And this sensation deepened as I tried to attend to Peter Enns, to read his books and listen to his videos, to comprehend his particular point of contention with historic Christianity.

What Are We Talking About?

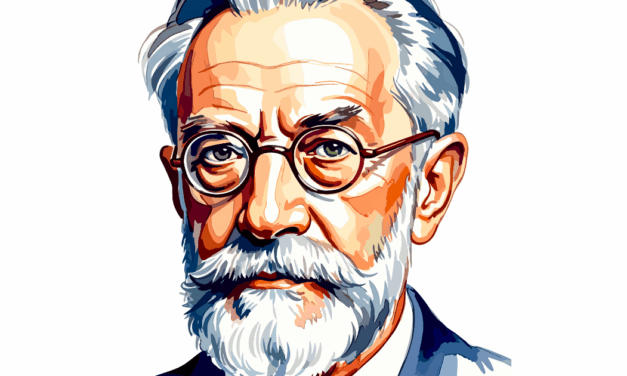

Holding a PhD from Harvard University, Peter Enns served as a tenured full professor of Old Testament and Biblical Hermeneutics at Westminster Theological Seminary — arguably one of the most prestigious chairs in evangelical scholarship. He currently holds a professorship in Biblical Studies at Eastern University and has lectured widely in both seminary and doctoral programs.2 His impact on evangelical leaders is immeasurable. On YouTube, he enjoys “ruining” biblical texts on The Bible for Normal People podcast.

Enns burst onto the evangelical scene in 2005 with a book called Inspiration and Incarnation: Evangelicals and the Problem of the Old Testament (Baker Academic). The premise seemed promising: just as Jesus is fully God and fully man, so also the Bible is authored by mortal men and yet is inspired by God. The trouble evangelicals have had, Enns believes, is that they have too narrow a view of the text. It is read, too often, as though it is a list of rules or a place to find answers to life’s problems. In fact, for Enns, the Bible is a product of the cultures in which it was written.

We mortal creatures have a hard time holding two seemingly contradictory ideas in tension. Presented with a paradox, most of us will lean one way or another, letting go of whichever idea is hardest to grasp. Enns is no exception and, as his work of “incarnating” the Scriptures progressed, he gradually let go of the “divine” portion of the equation. Dogged theological adherence to the content of the Christian faith, according to Enns, is incompatible with the kind of trust in God a Christian should experience. The one, in fact, works against the other. In his memoir, Curveball, he insists that “Any intellectualized system of beliefs about God must minimize ‘subjective’ things like love and experience in favor of right ideas.”3 These “right ideas,” he says, “are not downloaded from heaven but created throughout history in the context of subjective human experience.” “From its very biblical beginning,” Christianity has been “highly relational and experiential” not “just the maintenance of a lengthy list of beliefs.”4

For Enns, who perhaps missed the import of the rather trite, but nevertheless true quip about Christianity that it is a “relationship” not a “religion,” the dividing line between experience and propositional truth means that “Our God-talk is invariably tied to our humanity. This means to me that we should be open to conversing in love with anybody about anything, even those ideas that we see as central and nonnegotiable.”5 Some of the “ideas” that Enns believes should be negotiable, or, another favorite term, “adapted,” are the sovereignty of God,6 the perspicacity and inerrancy of the Bible,7 the historicity of biblical figures like Jonah8 and Abraham,9 the existence of hell,10 and the nature of God as distinct from the cosmos.11

Appealing to Richard Rohr’s assertion that faith isn’t best explained by something like the Wesleyan Quadrilateral, or Richard Hooker’s three-legged stool (Enns adopts a popular but errant reading of Hooker), but rather a tricycle whose front wheel is experience, he explains that, “By placing experience at the front, Rohr is not minimizing the role of the sacred text in the life of faith. He is simply acknowledging how our varied human experiences are what make us human and shape how we see absolutely everything, including scripture”12 (emphasis in original). The Bible, in other words, is a lot more human than divine, and as such, does not beget any particular obligation toward belief or obedience.

Did God Actually Say?

I find the acknowledgement by Enns that experience is the driver of faith revealing for at least two reasons. First, Enns often admits that he doesn’t “know” what he is talking about. “I was sitting there reading,” he relates in a podcast about his journey towards deconstruction. “I didn’t even know what I was reading, but I just sort of stopped reading, and I looked out the window and I said to myself, ‘I don’t understand the cross at all. I don’t understand the sense of it especially the way it’s usually portrayed as a necessary payment.’”13 Across books and podcasts he explains that his study of science and his experience of the natural world has rendered God so wholly “other” in his mind that he can’t make sense of the God described in the pages of Scripture. In one TED Talk–style address, Enns authoritatively declares that, though he loves to think about the Bible and God, he knows very little of what he is speaking.14 Every time I experienced Enns talking about how little he knows — usually at length — I felt baffled. Why is this his job then? I continually wondered. After a while it dawned on me that Enns’s effort to privilege his subjective experience over biblical revelation resembles the belligerence of Simon Magus, that obscure biblical figure who wanted the power and experience of the Christian faith without submitting to the revelation of Christ as his Lord (Acts 8).

Second, it’s important to grapple with — and then reject — the idea that “experience” might drive Scripture and reason down the road of faith because that is how many modern people conceive of what they are doing. Whatever Enns might say about it, human experience is not wholly subjective. We often incline toward knowable, objective realities beyond ourselves. When I get in a car, I bend myself to the concrete realities of the road, the steering wheel, the cost of insurance, and the existence of people on the sidewalk. When I hold my phone in my hand, I accept the world of apps and scrolling as the condition for my participation with an online world.

Human experience is not so varied that it admits infinite expressions of knowledge of the divine. On the contrary, humanity is stuck to the ground in a vast universe of space and stars, and galaxies. Enns is trying to reverse this process, to make reality conform to him rather than him to reality. This is what he calls “experience,” the business of bringing God into a realm he finds respectable. The trouble is, he ends up making the frame much smaller than the one most Bible-accepting Christians generally do. Why is it, we may ask, that the deconstruction of the Christian Bible always ends up producing a God who lacks power, agency, communicative abilities, and who may or may not exist?

Though Enns does not seem able to wrap his intellect around it, a principal reason Christians, historically, have accorded the Bible authority over both human reason and, for Protestants, ecclesiastical tradition is the emotional immediacy of the communication coupled with the coherence with which God speaks across so many centuries and in so many human voices. The text, in other words, is living. As generations of Christians have opened themselves up to it, by the power of the Holy Spirit, they have experienced the life-altering conviction and salvation that God promises.

God Himself says it — by the pen of Isaiah — “For as the rain and the snow come down from heaven” (of course we know that heaven isn’t “up,” Dr. Enns) “and do not return there but water the earth, making it bring forth and sprout, giving seed to the sower and bread to the eater, so shall my word be that goes out from my mouth; it shall not return to me empty, but it shall accomplish that which I purpose, and shall succeed in the thing for which I sent it” (Isaiah 55:10–11). 15 The Word of God is different from all human words because it has power. It is the means by which God effects His will in His creation.

It is, of course, possible to throw up a cloud of exegetical smoke over this point by saying there were different “Isaiahs” at different points in Israel’s post-exilic history, and that because the Bible is authored by both God and man, the reader must leap through various socio-historical hoops to “really” understand what the writer is trying to say.16 It is possible because that is Enns’s peculiar task, and he does it relentlessly. The heavens are not literally “higher” than the earth (Isaiah 55:9). There are no heavens, in fact, only a lot of space. Therefore, you may feel in your very soul the joyous meaning of these words, but you must not be carried away by the poetry. Quantum science has debunked the “biblical view of the cosmos.” Thus, it is almost impossible to understand what God might be saying. If He has “thoughts” and “ways” (Isaiah 55:8), He hasn’t put them into coherent speech.

What Happened?

Enns objects to the Bible on the grounds that it is not “historical.” The events recorded in the various texts often didn’t happen the way the writers say they did. In fact, the writers themselves do not expect you to read the book as a factual record of events that definitely took place. Jonah is an allegorical person who was never swallowed by a large fish and did not preach to Nineveh — and certainly Ninevah never repented. The way the story is told is meant to communicate that it is not a real event in space and time. “It’s a parable to challenge its readers to reimagine a God bigger than the one they were familiar with”17 (emphasis in original). Likewise, Adam is not a historical person. He wasn’t created by God and placed in a literal garden. He didn’t fall into sin by being tempted by a talking snake. Talking animals are absurd. When you encounter them in the text, you are meant to think in terms of stories and myths and not history. Likewise, the flood did not cover the whole world. The other, extra-biblical ancient texts that mention a worldwide catastrophic water event somehow also verify that it did not cover the whole world.18 Manasseh, the worst king of Israel, was not taken away captive to Babylon, did not literally repent, and was not then restored to his throne. He is an allegory for what happened to Israel as a whole.19 But what about Jesus, you might wonder. Isn’t He one of the most well-documented figures in human history? Enns isn’t sure about the historicity of Jesus. 20

For Bible-accepting Christians, being able to trust those portions of Scripture that hold themselves out as historical is essential for the experience of faith. Where Enns, through a false choice, severs the mind from the heart and belief from reason, it is the historicity of these texts that for Christians, reconciles those two broken fragments.

It comes down to the question of Jesus. If Jesus did live in the time the biblical narrative says He did, if He did die on a cross, and if He did rise again — not allegorically or merely in the “hearts” of His followers, but in His body — then the way the Old Testament is read has to be reconsidered by materialists and secularists. If Jesus rose again, then His claim to be God is vindicated. If He is God, then what He says about the Scriptures must at least be considered plausible. And for Jesus, Adam (Matthew 19:4–6), Jonah (Matthew 12:38–41), Moses (John 5:45–47), and Abraham (John 8:31–58) were all real historical people.

Enns passes over the claims the Bible makes about itself, its internal coherence, its divine authorship, with a three-fold deconstruction. The text, he says, is “ancient, ambiguous, and diverse.”21 Its very age, explains Enns, “shows us the need to ponder God anew in our here and now,” a task which takes “creative imagination to bridge the ancient and modern horizons.”22 In fact, the creative imagination required is a process found within the Bible itself as each writer makes sense of other authors’ experiences. It’s ambiguity, he says, is that it “doesn’t actually lay out for anyone what to do or think.” It doesn’t “hand out answers.”23 And finally, its diversity rests in the fact that “it does not speak with one voice on most subjects,” but rather with “conflicting and contradictory voices.”24 The biblical writers “demonstrate to us with blinding clarity that they were human beings like us whose perceptions of God and their world were shaped by who they were and when they lived.”25 It’s a mystery, he declares, and then proceeds to throw over the mysteries replete throughout the text and the cosmos by insisting that death directed the entire project.

Devolving Faith

Enns doesn’t believe in a literal Adam who tended a Garden with the help of his wife. In fact, in the first few chapters of Genesis, God has taken pains to show the reader that it cannot be viewed through a historical lens at all. The creation of the world is imagined through metaphors of chaos and order. Rather than God bringing forth the cosmos by the power of His Almighty Word, allowing that creation to fall into sin, and then setting out to redeem and restore it, God is inviting each person to discover his or her own spiritual path.

For Enns, it was the realization that ancient people held a view of the world that we don’t share because of our scientific progress that opened the text for him. “For much of Jewish and Christian history,” he writes, “the cosmos was thought to be more or less stable and fixed, that which God created ‘in the beginning’ and forever shall be until the end of time. That universe was at least in principle a remotely graspable factor attesting to God’s power. But that stability and graspability have evaporated over the past hundred years or so. The size of the cosmos is one of the reasons why.”26

Enns is fascinated by the immense size of the cosmos. He spends several chapters of his memoir attempting to explain quantum physics and what it might mean for faith. Of one thing, however, he is certain: the Bible has described God and His relationship to His creatures, yet the advance of science renders that description less than useful. On the other hand, though the cosmos is so immense, yet we are subject to death, indeed, death drives the whole business of being human. “Suffering and death,” he explains, “rather than being alien to the world, were from an evolutionary point of view a necessary part of the process all along. Death actually propels evolution forward via random genetic mutations, natural selection, and the survival of the fittest. If it weren’t for this death-studded process, Christians, ironically, wouldn’t even be here to ponder whether evolution is true.”27

The trouble is, evolution only kills things, it doesn’t produce them. Both Enns and the biblical authors look at the sky in wonder in awe, but for the biblical authors, this wonder evokes praise for and faith in the God who made all things. For Enns, it sends him into a vortex of confused deconstruction that ends in praise-less unbelief. For the biblical authors, death, as the enemy, tears apart the holistic unity of body and spirit, life and creation, individual and community. For Enns, and all committed Darwinists, death is, bizarrely, the creator. It is strange that anyone would look to Enns for an understanding of God and the Scriptures since he so thoroughly repudiates both. The great irony, it seems to me, is that Enns is able to sit in the comfort of a well-appointed home and employ his soul — something evolution is not able to produce — towards debunking the glory of God.

There Is an Answer

“When we come to the Bible expecting it to be an instructional manual intended by God to give us unwavering, cement-hard certainty about our faith,” explains Enns, “we are actually creating problems for ourselves because — as I’ve come to see — the Bible wasn’t designed to meet that expectation”28 (emphasis in original). You can’t just crack it open and have all your questions answered. If you really have questions, you can follow Enns on TikTok and Patreon, or pay for some of his classes through The Bible for Normal People website.

Except that, for the deepest question of the soul, the existential one, the one about why you exist and what will happen when you die, there is very much an answer — Jesus. Jesus is always the answer. From the first stroke of the pen on the first page of Genesis until the final dot at the end of Revelation, all the words are about the Word who became flesh and dwelt among us (John 1:14), in whom we behold the Father (John 14:11). He is the Way to the Father. He is the Truth about everything. He is the Life — the kind that swallows up death forever (John 14:6).

To miss this about the Bible is to be the person with a nail jutting out of your head, insisting that everyone listen to your heartbreak and sorrow and never being willing to hear that you don’t have to go on that way, that there is a solution to all your problems, at least the ones that have consequences forever. Of course, everyone will be kind and listen to you, but you will be trading the wisdom of God for your own, and you will miss the most astonishing story of love the world has ever beheld.

Anne Kennedy, MDiv, is the author of Nailed It: 365 Readings for Angry or Worn-Out People, rev. ed. (Square Halo Books, 2020). She blogs about current events and theological trends on her Substack, Demotivations with Anne.

NOTES

- Jason Headley, “It’s Not About the Nail,” written and directed by Jason Headley, YouTube video, 1:41, May 22, 2013, https://youtu.be/-4EDhdAHrOg?si=bM-A0uL1E3e5Zmp9, emphasis in original.

- Peter Enns, PhD, Eastern University, accessed May 21, 2025, https://www.eastern.edu/peter-enns.

- Peter Enns, Curveball: When Your Faith Takes Turns You Never Saw Coming (or, How I stumbled and Tripped My Way to Finding a Bigger God) (Harper One, 2023), 126.

- Enns, Curveball, 126.

- Enns, Curveball, 127.

- Peter Enns, How the Bible Actually Works: In Which I Explain How an Ancient, Ambiguous, and Diverse Book Leads Us to Wisdom Rather Than Answers — and Why That’s Great News (Harper One, 2019), 186–89.

- Enns, Curveball, 28–30.

- Enns, How the Bible Actually Works, 105.

- Enns, Curveball, 19.

- Enns, Curveball, 158.

- Enns, Curveball, 76, 151.

- Enns, Curveball, 127.

- David Moses Perez, Peter Enns, “Is It Necessary to Deconstruct the Bible,” Iconoclast Podcast, YouTube video, February 5, 2024, 15:55–16:20, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eLViTS83dwg.

- Dr. Pete Enns, “Reimagining an Ancient God,” TheoEd Talks, YouTube video, 20:36, April 2, 2019, https://youtu.be/YDirRZLtifE?si=yk0TniULAancrekT.

- Bible quotations are from the ESV.

- For a good examination on who wrote the book of Isaiah, see Gleason Archer, A Survey of Old Testament Introduction, revised and expanded (Moody, 1996); Geoffrey W. Grogan, “Isaiah,” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Isaiah, Jeremiah, Lamentations, Ezekiel, ed. Frank E. Gaebelein, vol. 6 (Zondervan Publishing House, 1986), 6–11; Seth Erlandsson, The Scroll of Isaiah: Its Unity, Structure, and Message (Northwestern Publishing House, 2020); Edward Andrews, “How Many ‘Isaiahs’? A Question of Prophetic Authorship and Unity in the Book of Isaiah,” Christian Publishing House, November 7, 2024, https://www.christianpublishers.org/post/how-many-isaiahs-a-question-of-prophetic-authorship-and-unity-in-the-book-of-isaiah?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Enns, How the Bible Actually Works, 105.

- Peter Enns, Inspiration and Incarnation: Evangelicals and the Problem of the Old Testament, 2nd ed. (2005; Baker Academic, 2015), 40–55.

- Enns, How the Bible Actually Works, 109–112.

- Enns, How the Bible Actually Works, 206–207.

- Enns, How the Bible Actually Works, 5.

- Enns, How the Bible Actually Works, 8.

- Enns, How the Bible Actually Works, 8.

- Enns, How the Bible Actually Works, 8.

- Enns, How the Bible Actually Works, 9.

- Enns, Curveball, 70.

- Enns, Curveball, 102.

- Enns, How the Bible Actually Works, 4.