Listen to this article (10:30 min)

This article first appeared in the Christian Research Journal, volume 40, number 06 (2017). For further information or to subscribe to the Christian Research Journal please click here.

Scholars who hold a low view of the literal accuracy of the New Testament often imply that the authors of the Gospels deliberately included material that they had no reason to believe was true on the ground level of reporting, even fabricating incidents and altering details. Why? Because ancient people did not consider literal truth to be as important as we do today.1

We are told that it is anachronistic to think that John would have had any qualms about knowingly stating that Jesus cleansed the Temple three years earlier than He actually did, or that Matthew would have hesitated to include a fictional story about the Magi,2 since they would have regarded such fabrications as serving a higher truth.3

As a matter of historical inquiry, it is a dubious method to assume that the author of a supposedly historical work put in material that he himself did not believe to be true. A simpler assumption, often sufficient to explain the data, is that an author at least believed what he said.

TRUE WITNESSES

The presumption against deliberate invention and alteration of facts is especially strong in the case of the Gospels, since the subject matter was vitally important to the authors as well as to their audience in the early church. On the face of it, toying with the facts about the life of Jesus, the Son of God, would be a serious offense, as Paul says it would be if the apostles were false witnesses (1 Cor. 15:15). John emphasizes repeatedly that he is testifying truthfully (John 19:35, 1 John 1:1–3). Peter stresses the importance of bearing true witness about Jesus, both when choosing a successor to Judas (Acts 1:22) and when asserting that the apostles and their converts had not followed “cleverly devised myths” (2 Pet. 1:16).

It is a better historical method to assume, at least as a working hypothesis, that the authors of the Gospels were attempting to write truthfully, in a normal sense of that word. If they were either apostles themselves or close associates of the apostles, as strong patristic evidence asserts, then they were close up to the facts about the life of Jesus. And even if there is some literary dependence among the Gospels (especially Matthew, Mark, and Luke), the authors could be expected to have some independent knowledge of the events.

PERFECT PUZZLE PIECES

This working hypothesis can then be tested. What would we expect from four different truthful reporters with information close-up to the facts? If these reporters are even partly independent, we would expect to find that they would tell different parts of the same stories and that their stories would fit together to create a vivid, accurate picture. We might even find them filling in details and answering questions raised by each other, as often happens in witness testimony today.4

This is exactly what we do find, as I argue in Hidden in Plain View: Undesigned Coincidences in the Gospels and Acts.5 The feeding of the five thousand provides a good case study. Luke locates the event in a deserted area near Bethsaida (Luke 9:10–13). This is indirectly confirmed in John, when Jesus asks Philip where the disciples can buy bread to feed the people (John 6:5–6). Jesus did not seriously mean to suggest that they should buy bread for the crowd but asked the question to set up His intended miracle. Why does He ask Philip specifically? In completely different contexts in John (1:44, 12:21), we learn that Philip was from Bethsaida, so Jesus may well have been alluding to this fact in asking him where one could buy a large amount of food nearby. But nowhere does John say that the miracle took place near that town, nor does Luke mention the question to Philip.

This type of argument is cumulative, made up of many small indications. Here is another, related to the same incident: only John’s Gospel mentions that the feeding of the five thousand took place shortly before Passover (John 6:4), while only Mark emphasizes that the grass on which the people sat down was green (Mark 6:39). We know independently that the grass in that part of the world is green only at limited times of the year, one of them being around the time of Passover. So both the place and the time of the feeding are supported by minute coincidences of detail among the Gospels, casually mentioned. These are marks of truth, and they are all the more noteworthy because this story concerns a miracle.

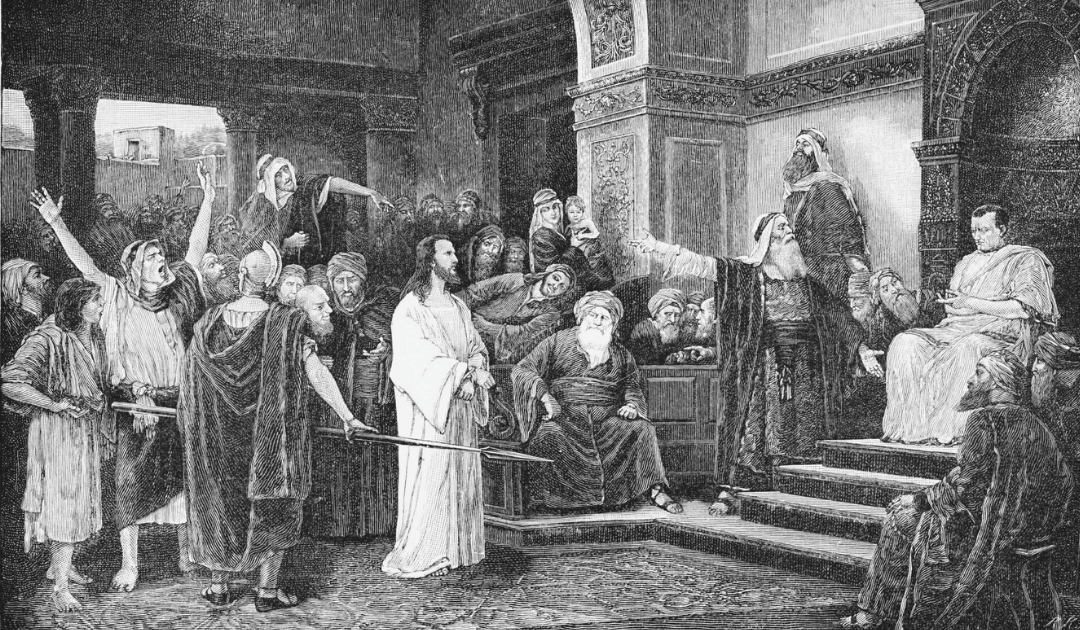

Jesus’ dialogue with Pilate is confirmed by similar coincidences between John and Luke, despite the fact that one might think that neither author would have known the specifics of what Jesus and Pilate said to each other. The view suggested at the outset would lead us to think that John might consider himself licensed to use literary artistry to make up dialogue where he had no actual knowledge. But on the contrary, we find details of the dialogue multiply supported. Jesus tells Pilate that His kingdom is not of this world and that if it were of this world, His servants would fight (John 18:36). The first part of this dovetails beautifully with Luke 23:3–4, which mentions that Pilate tells the crowd that he finds no fault in Jesus, despite Jesus’ apparently affirmative answer to his question, “Are you the king of the Jews?” Why would Pilate say a thing like that, since Jesus does not deny and even appears to accept the charge? Declaring oneself to be the king of the Jews would have been a very serious matter from Pilate’s perspective. In John, we find the rest of the story. Jesus said that He was a king, but not an earthly one.

Jesus’ assertion that His servants would fight if He were an earthly king raises a question. Why would Jesus say this, since Peter did try to fight in the Garden of Gethsemane, as mentioned in both John 18:10 and Luke 22:49–50? He cut off the ear of a servant of the high priest. In this case, Luke has the answer: Jesus, says Luke’s Gospel, healed the servant’s ear. Jesus could tell Pilate that His kingship was not of the revolutionary sort; if this claim were challenged, His enemies would be embarrassed when they were unable to produce the tangible evidence of Peter’s violence and instead had to admit Jesus’ generous healing miracle.

HISTORICAL DETAILS

These sorts of undesigned coincidences, as they are called, crisscross the Gospels in all directions, from the earlier books to the later, from the more similar three Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke) to John and back, from the mundane to the miraculous.

Another coincidence can be found in Matthew. We are told that Herod was superstitiously musing to his servants that Jesus might be John the Baptist risen from the dead (Matt. 14:2). How would Matthew know what Herod was saying to his servants? Perhaps Matthew just invented that detail to make a more interesting narrative. But no. Luke 8:1–3 says, in an entirely different context, that among the women who followed Jesus from Galilee and contributed to His ministry was Joanna, the wife of Chuza, Herod’s steward. Through this connection between the followers of Christ and Herod’s household, Matthew could well have known about Herod’s musings to his servants.

The author of Luke also wrote the book of Acts, and his literal accuracy finds further support in numerous coincidences between Acts and Paul’s epistles. Remarkably, although Acts never mentions that Paul wrote letters to the churches, it is possible to place several of Paul’s letters meticulously at specific points in Acts by using these clues. Acts 19:21–22 says that Paul sent Timothy and Erastus ahead into Macedonia while he remained in Ephesus for a time. These verses give Paul’s planned itinerary after leaving Ephesus: he intended to pass through Macedonia and Achaia and then go to Jerusalem, followed by a trip to Rome. If we compare these verses with Paul’s plans given in 1 Corinthians 16:1–10, we find that he was at that very time in Ephesus and was planning his future travel in exactly the way described in Acts 19. Paul also says in 1 Corinthians 16 that he has already sent Timothy on ahead and that Timothy may arrive in Corinth before he does, which fits perfectly with the statements about Timothy’s whereabouts in Acts. Paul would have been able to send his letter to Corinth from Ephesus, across the Aegean Sea, so that it would arrive before Timothy could, since Acts tells us that Timothy traveled by a longer route through Macedonia. All of these details (and more) support the conclusion that 1 Corinthians was written at precisely this place in the narrative of Acts, but they do so quite indirectly. It appears that the author of Acts knew, independently, Paul’s movements and even his plans.

Sometimes Paul tells the recipients of his letter that they already know about something, and this “as you know” creates a fascinating connection with Acts. In 1 Thessalonians 2:1–2, Paul is recalling his ministry to the Thessalonians. He says that he had suffered and been shamefully treated in Philippi, as the Thessalonians know, but that he nonetheless was bold to preach the gospel to them. What mistreatment is he talking about, and why would the Thessalonians in particular know about it? Paul doesn’t go into detail, since his audience would have known the circumstances. Acts tells the rest of the story in chapter 16, where Paul and Silas are beaten and imprisoned after exorcising a slave girl. Paul was quite indignant about this illegal treatment of Roman citizens, and after the famous “singing in the jail” episode, followed by an earthquake, he extracted an apology the next morning from the city magistrates (Acts 16:39). Now we come to the connection to the Thessalonians. Philippi and Thessalonica were both located in the province of Macedonia, and in Acts 17:1, Paul continues his travels through Macedonia and comes to Thessalonica, apparently not long after he and Silas were beaten in Philippi. Paul would have been smarting, figuratively and possibly literally, from that experience, and 1 Thessalonians leads us to believe that he told the Thessalonians about it. Thus we get a complete and satisfying picture by putting the letter and the historical book together.

This indicates that the author of Acts reported accurately both the events in Philippi and Paul’s order of travel and ministry immediately afterward. But Acts shows no signs of being dependent on 1 Thessalonians. As I discuss in Hidden in Plain View, Paul’s ministry in Thessalonica appears (from the epistle) to have been longer than one would guess from a cursory reading of Acts 17. This shows that Acts was not based on the letter. As with the Gospels, these are just a few examples of the many connections between Acts and Paul’s writings.

As the evidence mounts up, the most reasonable conclusion to draw from these coincidences is that the authors of the Gospels and Acts were trying to get it right in a perfectly ordinary sense and, moreover, that they succeeded. They seem to have been remarkably well informed and truthful even on many matters of mundane detail, rather than inventing these or taking them from unreliable sources. It is not merely some minimal “core” of the events that we should take to be intended as literal, historical reportage. The more we study the books of the New Testament, the more we find our confidence in them justified as highly reliable witnesses to the life of Jesus and the beginning of the church.

Lydia McGrew, PhD, is a homeschooling mother and a widely published analytic philosopher with specialties in classical and formal theory of knowledge, probability, and philosophy of religion. She has recently published Hidden in Plain View: Undesigned Coincidences in the Gospels and Acts (DeWard Publishing, 2017).

NOTES

- Richard Burridge, Four Gospels, One Jesus? A Symbolic Reading (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2005), 169–70.

- Michael Licona suggests that Luke and Matthew may have invented the nonoverlapping portions of the infancy stories to “create a more interesting narrative of Jesus’ birth.” He erroneously calls such wholesale invention “midrash”; https://thebestschools.org/special/ehrman-licona-dialogue-reliability-new-testament/licona-detailed-response/.

- Michael Licona, Why Are There Differences in the Gospels? What We Can Learn from Ancient Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 115.

- Warner Wallace, Cold-Case Christianity: A Homicide Detective Investigates the Claims of the Gospels (Colorado Springs: David C. Cook, 2013), 187.

- Lydia McGrew, Hidden in Plain View: Undesigned Coincidences in the Gospels and Acts (Chillicothe, OH: DeWard Publishing, 2017).