This article first appeared in the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL, volume 31, number 02 (2008). The full text of this article in PDF format can be obtained by clicking here. For further information about the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL, click here.

SYNOPSIS

It has become virtually impossible to escape encounters with yoga in one form or another in the course of daily American life. For the conscientious Christian the question becomes inescapable: “Is yoga, or can it be, compatible with the Christian faith?” To answer this question we must first understand yoga in its original Hindu context.

Yoga was developed by Patanjali, a philosophical dualist, to free the souls of human beings from what he believed was their false identification with matter. Yoga later was appropriated by Vedantists (pantheists) and became a method for achieving union with the impersonal God of Hinduism.

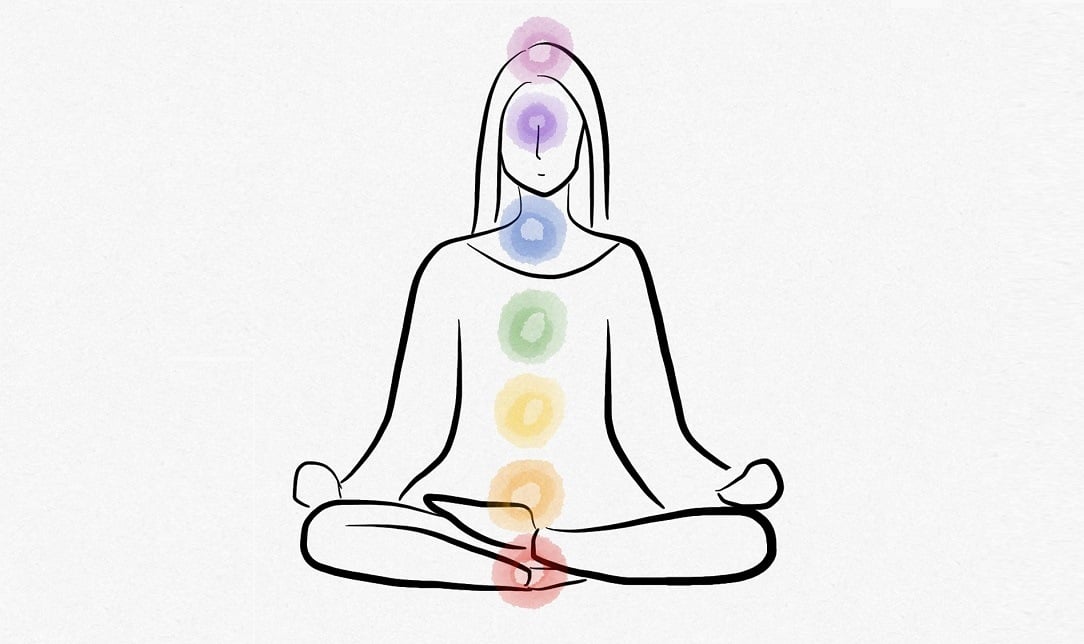

Classical yoga seeks to so discipline the mind that the practitioner no longer identifies his (or her) thoughts and sensory perceptions with his sense of self. It also seeks to release a life force called prana so that it may freely move through the human body via seven psychic centers called chakras. These objectives are accomplished by following Patanjali’s eight limbs of yoga, which include moral, physical, and mental disciplines.

There are four major approaches to yoga in India: bhakti yoga is devotion to a personal God; Jnana yoga involves intellectual discretion; karma yoga emphasizes good works; raja yoga is concerned with mind control and consists of the eight limbs of Patanjali. Within raja yoga exist numerous distinctive minor approaches, including kundalini yoga, which seeks enlightenment through raising the serpentine “kundalini energy”; tantra yoga, which seeks enlightenment through uniting polar energies, sometimes involving illicit behavior; and hatha yoga, which seeks enlightenment indirectly by preparing body and mind for meditation. Whether hatha yoga can be separated from its Hindu roots and practiced by Christians will be a major subject in parts two and three, which will examine yoga in its contemporary Western context.

Yoga is big. But then, I don’t need to tell you that. It is impossible to live in our Western culture these days without encountering yoga on a regular basis, from one’s own workplace or school to the local hospital or YMCA, from one’s own neighbors, friends, or family to the local newspaper, television, or church.

Yoga has been present in the United States for well over a century,1 but since the 1990s it has rapidly mainstreamed, moving from cultural fad to cultural institution. An article in the Columbia Journalism Review in late 2006 gives a sense of the magnitude of the yoga boom:

Everybody loves yoga; sixteen and a half million Americans practice it regularly, and twenty-five million more say they will try it this year. If you’ve been awake and breathing air in the twenty-first century, you already know that this Hindu practice of health and spirituality has long ago moved on from the toe-ring set. Yoga is American; it has graced the cover of Time twice, acquired the approval of A-list celebrities like Madonna, Sting, and Jennifer Aniston, and is still the go-to trend story for editors and reporters, who produce an average of eight yoga stories a day in the English-speaking world.…

…Down the hall in marketing, this kind of press is the stuff of dreams. Yoga has now ascended to the category of “platform agnostic,” the highest praise marketers can conjure for any kind of content, trend, or person. Translation? Consumers drop $3 billion every year on yoga classes, books, videos, CDs, DVDs, mats, clothing, and other necessities.2

With yoga appearing at virtually every turn one takes in Western culture, including the church,3 a probing Christian analysis of yoga is urgently needed. This three-part series will provide that by answering the question, “What is yoga?” in part one, and then, in parts two and three, identifying and responding to the areas where it touches our lives today.

WHAT IS YOGA?

Yoga is derived from the Sanskrit word yug, which means “to yoke.” This is a term we’re familiar with from the Bible (Phil. 4:2; Matt. 11:9). A yoke is a crossbar that joins two draft animals at the neck so they can work together; the term, therefore, is applied metaphorically to people being joined together or united in a cause. In Hinduism, as in many religions, union is desired with nothing less than God or the Absolute, and yoga is the system that Hindus have developed to achieve that end.

The historic purpose behind yoga, therefore, is to achieve union with the Hindu concept of God. This is the purpose behind virtually all of the Eastern varieties of yoga, including those we encounter in the West. This does not mean it is the purpose of every practitioner of yoga, for many people clearly are not practicing it for spiritual reasons but merely to enhance their physical appearance, ability, or health. The thesis I will be arguing in this three-part series, however, is that when someone participates in a practice that was developed with a specific purpose in mind by someone else, it is possible and even probable that on subtle levels the participant who does not have the original purpose in mind nonetheless will be moved along in the direction of fulfilling that purpose.

Historical and Conceptual Foundations

The yoga system was reputedly developed by the grammarian and Hindu sage Patanjali most likely between the third and second century B.C. Archaeological finds suggest that yoga in some form has existed since around 3,000 B.C., but in his Yoga Sutras (i.e., yoga aphorisms) Patanjali presented the system that we’re familiar with today. The aphorisms are condensed, close to two-hundred in number, and divided into four chapters. Their main concern is the control of the mind.

It may come as a surprise to Westerners to learn that yoga was not originally based in a monistic (“all is one”) or pantheistic (“all is God”) philosophy. In India Hinduism is incredibly varied. About the only common elements in all forms of Hinduism are belief in karma (the law of cause and effect on a moral plane) and samsara (the cycle of rebirth), and practice of some form of yoga. At the time that Patanjali developed yoga, the dualistic philosophy of Samkhya (or Sankhya) was prominent in India. Samkhya held that there are two fundamental realities: (1) parushas, or individual, immaterial, eternal, and indestructible souls, and (2) prakriti, which forms the material world, and itself consists of three basic elements known as the three gunas: Sattva (goodness/truth), Raja (passion/activity), and Tamas (darkness/inertia).

According to Samkhya-Yoga philosophy, when these three primary elements are in equilibrium the world is unmanifest—all there is to prakriti is the three gunas existing in perfect harmony. There is something about the simultaneously and independently existing parushas, however, that at times mysteriously disturbs this equilibrium. When this happens the conflict between the gunas creates change and a variety of forms, with the world manifesting as a result. Throughout the history of the world one or the other of the gunas will be in the ascendant, causing goodness, passion, or darkness to dominate the epoch, until the gunas at long last reach equilibrium again and the world disappears.

The other important development in this drama is that the parushas become captive to prakriti. It is believed that out of a desire to understand the nature of prakriti they venture into it. As they come into contact with the material world, their pure consciousness generates mind and thought, which are believed to be part of prakriti and not proper attributes of parusha. The parushas’ sensations and perceptions create false egos in which they believe they are a part of the material world, and this belief entangles them in it. This bondage takes the form of transmigration of souls from one body to another and ultimately reincarnation, once the parushas reach the human level.

In their transmigrational journeys the parushas become entranced and captivated by the interplay of the gunas, which holds them in bondage to prakriti. Yoga therefore was developed by Patanjali as a method and means to facilitate the souls’ moksha or deliverance from its identification with prakriti.

The whole goal behind yoga, then, was for the yogi (yoga practitioner) to escape the goodness, passions, and darkness of the gunas and to reestablish the original pure state of consciousness of the parushas. He (or she) was to accomplish this by disengaging from his thoughts, feelings, imagination, and all the different tricks of his mind that hold him in bondage to the material world. It is a program to free him systematically from identification with his supposedly ephemeral ego so that he can identify once again with his true self, the parusha. In the Yoga Sutras, Patanjali teaches a method of mind control that involves counteracting painful thoughts with thoughts that are not painful, then learning to quiet the “not painful” thoughts as well.

This entire process of prakriti manifesting as the world and then returning to its unmanifest state was believed to recur on an eternal, cyclical basis, and it later, within a pantheistic philosophical system, became known as “the Days and Nights of Brahman.” Indeed, all of these concepts and terms were retained when absolute monism became prominent in Hinduism.

Hinduism was originally polytheistic (believing in many gods), and in some significant ways still is. Beginning, however, with the Upanishads (scriptures appended to the original Hindu scriptures, the Vedas, beginning around the eighth century B.C.), progressing through sacred texts such as the Bhagavad Gita (Hinduism’s most beloved scripture, penned perhaps in the second century B.C), and culminating in the eighth-century A.D. philosophy of Advaita Vedanta that the philosopher Shankara developed, monism and pantheism became important belief systems within Hinduism. For this reason, many Hindus now understand parushas, prakriti, the three gunas, and moksha to exist against the backdrop of a fundamental Oneness of Being that is the impersonal Ultimate Reality known as Brahman. In other words, instead of ultimate reality being parushas and prakriti, it is the impersonal Brahman, within which, in a relative sense, exist parushas and prakriti. As yoga was transferred into this philosophical system, the pure consciousness that the yogi sought to identify with was now not merely his own soul (now more often called atman than parusha) but that of God (for it is believed that atman is identical to Brahman).

Liberation of the soul from its bondage to the material world is a central goal of all orthodox schools of Hindu philosophy, and for each school, some system of yoga is the means for achieving this end. Yoga also has been appropriated in the same manner by many Buddhist sects, Sikhism, Jainism, Taoism, and various occult/metaphysical traditions in the West (e.g., Theosophy and the Unity School of Christianity).

The Eight Limbs of Yoga

Classical yoga practitioners are not interested in making their minds permanently blank, but rather to so discipline their minds that they no longer identify thoughts and sensory perceptions with their sense of self. This is accomplished by following Patanjali’s eight limbs of yoga.

The eight limbs of yoga involve strict moral, physical, and mental disciplines. They are (1) moral restraint, (2) religious observance, (3) postures (asanas), (4) breath control (pranayama), (5) sense withdrawal, (6) concentration, (7) meditative absorption, and (8) enlightenment (samadhi). A consideration of the limbs quickly reveals that yoga is a demanding autosoteric (salvation based on self-effort) system, similar to original Theravada Buddhism with its eightfold path, which historically preceded Patanjali’s yoga system and probably influenced it.

Limbs 1 and 2 pertain to the exercise of the will. It is important for the yogi to restrain himself from violence, lying, immorality, theft, and greed. It is also necessary for him to observe or practice purity, contentment, religious fervor, study of self, and surrender to God. He is to replace thoughts that are contrary to these virtues with their opposites.

Asanas and pranayama are the two limbs of yoga that exercise the body. They were not originally intended to be isolated from the other limbs of yoga, but that is what has happened to a great extent in the West through the promotion of hatha yoga, which is predominantly comprised of these two limbs (although meditation is often included or encouraged at the end of the session). It should be noted that in the Yoga Sutras one does not find the emphasis on stretching the body into unusual poses that is now associated with yoga, mainly through the influence of hatha yoga. Patanjali’s expressed concern was for the practitioner to assume “steady and easy” postures that would be conducive to meditation.

Sense withdrawal, concentration, and meditative absorption are the mental exercises of yoga. To develop the desired pure state of consciousness it is necessary to withdraw from the input of one’s senses and to develop one’s powers of concentration. To achieve this one might practice concentrating on a sound (e.g., one’s own chanting of a mantra, such as the name of a Hindu god or the sacred syllable om, which Patanjali says is the voice of God [1:27]), on an image (e.g., the tip of one’s nose or a symbolic religious image known as a mandala), or on one’s own breathing. The purpose, however, is to so focus on an object that the object itself disappears and a state of pure (i.e., thoughtless) consciousness is attained. Through these mental exercises and techniques, meditative absorption is achieved, where the practitioner begins to lose the distinction between subject and object (i.e., self and not-self), to experience the cosmic consciousness (i.e., the sense that one’s own mind is merging into a larger, Universal Mind), and to feel one with the Universe or God.

Diligent and persistent observance of the first seven limbs of yoga ultimately will yield samadhi, the eighth limb, which is defined as direct knowledge, free from the distortions of the imagination. When samadhi is achieved the yogi is finally free from the influence of the three gunas, which, as we’ve seen, has been the goal of yoga practice all along. Unlike everything else in creation, the yogi who achieves samadhi no longer is bounced around between the pulls and pushes of purity, passion, and darkness, but becomes sublimely indifferent to everything in the material world.4

On achieving samadhi, the yogi is believed to accumulate karma no longer. The only remaining karma for him to work out is that which was accumulated before attaining enlightenment. Once that remaining karmic debt is balanced the yogi will have achieved moksha or deliverance/salvation and his long and wearisome transmigrational journey finally will be over.

Prana and the Seven Chakras

Also important in the philosophy and practice of yoga are the concepts of prana and the seven chakras. Prana is the Hindu concept of a life force that pervades the universe. Prana is believed to flow through the human body by way of energy pathways called nadis through seven chakras (from the Sanskrit word meaning wheel or disc), which are psychic energy centers located at critical points up and down the human nervous system.

The first chakra, called muladhara, is believed to be located at the base of the spine and is associated with the guna tamas, and therefore with darkness, dullness, and animal instincts. It represents physical survival and it is associated with the most primitive state of human consciousness possible. The kundalini energy (see “Kundalini Yoga” below) sleeps within this chakra, waiting to be aroused, and its eventual rise to each ascending chakra is also an assent to a relatively higher state of consciousness.

The second chakra, swadhistana, is located in the region of the genitals. This chakra is associated with the guna Raja, and people who are under its influence are, of course, obsessed with sex.

The third chakra, manipura, is believed to exist in the area of the navel and is called the power chakra. It too is associated with the guna Raja, and people who are living at the level of this chakra are driven by ambition and the desire for power or success.

The fourth chakra, known as anahata, is the heart chakra. It and all subsequently ascending chakras are associated with the guna Sattva, until one reaches the final, crown chakra, which transcends the gunas. The heart chakra is associated with selfless emotion.

The fifth chakra, visuddha, is located in the region of the larynx. It is associated with asceticism, spiritual discipline, and the beginnings of mystical experience.

The sixth chakra, ajna, is located above and between the eyes (hence the concept of the “third eye”). It represents the vision of God and is considered a very high spiritual level from which to live.

The seventh chakra, “sahasrara or ‘Thousand Petalled-Lotus,’ located at the very top of the head, is technically speaking not a chakra at all, but the summation of all the chakras.”5 It represents samadhi, and so someone living at this level would be regarded as enlightened. In the entire universe, nothing escapes the influence of the gunas except those who have attained samadhi. Whereas the sixth chakra is “conditioned rapture,” the seventh is “unconditioned rapture.”

APPROACHES TO YOGA

There are so many varieties of yoga that a person trying to keep up with them can easily become lost. Part of the confusion comes from the fact that the term yoga is used for entire life approaches to union with God that may not even involve sitting in yogic postures, controlling one’s breath, and concentrating on a mantra or mandala. Three of these major approaches—bhakti, Janna, and karma—are also known as margas or paths to moksha. The fourth major approach to yoga or union with God—raja yoga—is essentially the eight limbs of Patanjali that includes everything we normally associate with yoga. For this reason it is also known as ashtanga (eight-limbed) yoga. Then, within the larger category of raja yoga are many subcategories or minor approaches that also have distinctive names, adding to the confusion. Some of these involve only aspects of raja yoga (e.g., hatha yoga and Transcendental Mediation6); others are distinctive approaches to raja yoga that involve all eight limbs but have their own distinguishing emphases (e.g., kundalini yoga and tantra yoga). There is also much overlap among the various yoga approaches so that elements of one approach are often employed by people who identify themselves as practitioners of another approach. I will do my best to sort it all out for you.

Bhakti Yoga

Bhakti yoga seeks salvation through the path of devotion to a personal representation of God. During the centuries that preceded Patanjali, India had been dominated by the atheistic or nontheistic philosophies of original Buddhism, Samkhya, Jainism, and the impersonal God of the Upanishads. The impulse to worship and serve a personal God (which a Christian would consider God-given) therefore had long been frustrated. Patanjali himself made a place for this, even though it was not a necessary part of his philosophical system. In chapter 1, verses 23–26 of the Yoga Sutras, he included the concept of Ishwara (or Ishvara), the personal God. Ishwara was not considered to be the creator God but was rather the supreme parusha, untouched by prakriti and the law of karma, who assists all parushas who are devoted to him in attaining moksha.

Like other concepts in Patanjali’s belief system, Ishwara survived the assimilation of yoga into the monistic Vedanta belief system, and he was now believed to be the personal manifestation of the impersonal Brahman. The dominance of Shankara’s unqualified monism created an acute longing in the hearts of many Hindus for a personal relationship with the divine, since God was believed to be impersonal and not separate from one’s true self. Ishwara helped fill that need, as did devotion to the various gods and goddesses of Hinduism and also to gurus, who were often believed to be divine; yet none of these gods were satisfying to those who wanted a personal relationship with Ultimate Reality Itself.

This need ultimately would be addressed by Ramanuja, one of the great philosophers of Hinduism who lived during the eleventh and twelfth centuries A.D. Ramanuja turned the tables on Brahman and argued that the impersonal nature of God was secondary to the personal, and Ishwara (whom he identified with the second god in the Hindu trinity, Vishnu, the god of preservation) is Ultimate Reality. There is thus a theistic school within Hinduism, although this version of theism is panentheist (known as Vishishtadvaita or qualified monism), meaning that everything exists within God, but everything is not God. In other words, the world and souls are real but they are also part of God’s being, not separate from Him, as in Christianity.

In the sixteenth century, a bhakti yogi named Chaitanya (or Caitanya) went a step further and argued that Krishna, who was believed to be an avatar (incarnation or manifestation) of Vishnu, actually is just another name for Vishnu and that Krishna is thus the supreme personality of the Godhead. The Hare Krishna cult (the International Society of Krishna Consciousness, or ISKCON), fully within Chaitanya’s movement, provides a good example of bhakti yoga in the West, with its devotional dancing, chanting, and singing of the names of Krishna, as well as its worship and ritualized care of its “deities” (idols).

Jnana Yoga

Jnana yoga could be described as “yoga for intellectuals” or “yoga for philosophers.” It seeks salvation through intellectual knowledge and discrimination. Hindu philosophers Shankara and Ramanuja are the ultimate examples of Jnana yogis, but any yogi who trains his mind to distinguish truth from falsehood would be on this yogic path.

Discrimination is not sufficient in Jnana yoga but must be accompanied by three other means of salvation: detachment from temporal concerns (but not necessarily withdrawal from them), virtue, and longing for liberation.7 Some form of meditation is also essential as a means of intuitively and experientially taking possession of the truth that has been logically discerned.

Karma Yoga

Karma yoga is yoga for idealists, humanitarians, activists, and ordinary people who want to pursue salvation but are unable to pursue monastic life. It seeks salvation through good works. These works can be social service or simply doing one’s job well. There is a catch, however: the karma yogi will gain nothing spiritually from his actions unless he performs them with no desire for the consequences of the actions, with no attachment to the action itself, and without viewing himself as its author, but rather, viewing God as the author of the action.

Prominent Los Angeles yoga teacher Bikram Choudhury clearly explains the role of karma yoga in attaining salvation:

Generally, a work brings as its effect or fruit either pleasure or pain. Each work adds a link to our bondage of Samsara and brings repeated births. This is the inexorable Law of Karma. But, through the practice of Karma Yoga, the effects of Karmas can be wiped out. Karma becomes barren. The same work, when done with the right mental attitude…does not add a link to our bondage. On the contrary, it purifies our heart and helps us to attain salvation through the descent of divine light or dawn of wisdom.8

Raja Yoga

Raja or “royal” yoga is the method of seeking salvation through mind control. It is believed that the mind is a fine part of the body, or the body a gross part of the mind (such that the two words are often conjoined in yoga literature as bodymind), and so if the yogi can learn to control his body he can also control his mind. This belief in the interrelationship between body and mind is the basis for yoga’s emphasis on physical disciplines and postures, since it is believed that they will help the yogi achieve the pure state of consciousness that is the goal of classical yoga.

Swami Vivekananda, perhaps yoga’s most respected missionary to the West and virtually the first, wrote: “According to the Raja-Yogi, the external world is but the gross form of the internal, or subtle.…The man who has discovered and learned how to manipulate the internal forces will get the whole of nature under his control. The Yogi proposes to himself no less a task than to master the whole universe, to control the whole of nature.”9

Vivekananda stressed that yoga was the perfect religion for the scientific Western culture that was losing faith in its theistic roots: “Each one of the steps to attain Samadhi has been reasoned out, properly adjusted, scientifically organised, and, when faithfully practised, will surely lead us to the desired end.”10 How can a religious discipline be considered scientific? The answer is that within a monistic system there can be no division of the supernatural from the natural. All is one; thus all spiritual phenomena have their explanation in natural laws. When a yogi masters the “whole of nature” he has conquered and can now manipulate God Itself.

Raja yoga is distinct from any other approach to yoga in that it can include or provide a larger context for all of the other approaches, including the minor approaches listed below. In this sense, almost this entire two-part article is about raja or ashtanga yoga, in one aspect or another.

Kundalini Yoga

Kundalini yoga deliberately attempts to arouse and raise the kundalini, believed to be Shakti or creative divine energy, which sleeps at the base of the spine like a serpent, coiled in three and one-half circles. Toward this end, kundalini yogis place a special emphasis on pranayama or breathing exercises in order to gain control of the respiratory system, which they believe will lead to control of other systems and ultimately of the entire body, including the kundalini. Visualization of the kundalini rising is also a common approach, based on the assumption that visualization of itself has the power to effect that which it visualizes. Kundalini yogis also use asanas, mudras (hand positions), chanting mantras, and meditation to raise the kundalini. A classic object of meditation is the seven-petaled lotus flower, which represents the seven charkas.

The one-thousand-petaled lotus, often seen in visionary experiences, represents the crown chakra. Raising the kundalini often results in powerful mystical experiences and visions, as a devotee of the late kundalini yoga teacher Swami Muktananda explains:

When this sleeping Kundalini is awakened it raises its [serpentine] hood. The door of the Sushumna [a nadi or energy conduit] is opened and the Kundalini ascends upwards along the Sushumna piercing through the six chakras (centres) situated in it. When it reaches the highest centre, called Sahasrara, in the crown of the head, it unites with the Lord Shiva [the god of destruction, third in the Hindu trinity, whose consort, Shakti, is identified with the kundalini]. This union brings ineffable joy of Blissful Beatitude. …it gives various mysterious experiences to the sadhaka [i.e., yogi], who himself is struck with wonder by them.…The experiences in the gross body are such as tremors, heat, electric shocks, perspiration, tears, thrill of joy, palpitation, involuntary suspension of breath or deep breathing, revolving of eye-balls.…The experiences in the subtle body are such as visions of deities and divine beings, receiving instructions from them; hearing sounds like those of conch, bell, flute, drum, thunder.…Under the guidance of the Guru, the sadhaka should proceed with the spirit of surrender allowing the Shakti to manifest itself unobstructed while himself remaining as a witness to its working. He should not try to avert an experience through fear. The Shakti is intelligent. It is aware of its own activity. Hence nothing ever goes wrong. Besides, the Guru is always there to control its flow.11

Yogis believe kundalini phenomena are the true explanation for visionary experiences in all religions. According to their interpretive grid, anyone who has a spiritual experience has to some degree aroused the kundalini, but if he is not properly trained by a guru he will misinterpret his experiences (e.g., when Muhammad heard the voice of the angel Gabriel) and likely develop unhelpful or even harmful beliefs.12

In a manner somewhat comparable to LSD, raising the kundalini is considered risky, with temporary madness, lasting mental instability or illness, and occult oppression being possible consequences.13 Many yogis thus warn against the practice for most people and condemn yogis who indiscriminately teach it to the public.

Tantra Yoga

Tantra is an esoteric (occult) religious tradition that originated in Hinduism but also exists in Buddhism and other Asian religions. Many orthodox Hindus regard it with suspicion or outright disdain because of its disregard for, or outright rejection of, the primary Hindu scriptures, the Vedas. It nonetheless does hold to many of the core Hindu doctrines, but with its own twists.

For example, while it agrees with Advaita Vedanta that Brahman is essentially Being, Awareness, and Bliss (called Sat-Chit-Ananda in Sanskrit), that Brahman is all there is, and that the world is maya or illusion, it defines maya differently, not merely as illusion but as a real operation within the nature of Brahman. The true essence of the world and souls is Sat-Chit-Ananda, but they are nonetheless real. Maya therefore consists of Brahman’s evolution from undifferentiated oneness into the multiple forms of the world (prakriti) and also of Brahman’s involution from the world back into undifferentiated oneness. Swami Nikhilananda, founder of the Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center of New York, expounds on this important aspect of Tantric belief:

Evolution or the “outgoing current” is only one half of the functioning of Maya. Involution, or the “return current”, takes the jiva [i.e., soul] back towards the source or root of Reality, revealing the infinite. Tantra is understood to teach the method of changing the “outgoing current” into the “return current”, transforming the fetters created by Maya into that which “releases” or “liberates”. This view underscores two maxims of Tantra: “One must rise by that by which one falls” and “the very poison that kills becomes the elixir of life when used by the wise.”14

Tantra yogis have many ritual practices that seek to embrace the dualities of prakriti (as best represented by the god Shiva and his consort Shakti) and unite them, thus transmuting the energy of evolution into the energy of involution, which they believe will result in their own enlightenment. This approach calls for participating in activities that are normally renounced by Hindus seeking enlightenment, such as eating meat, consuming alcohol, and having sexual relations. Tantrists believe that if they can maintain a transcendent state of consciousness throughout such activities they will unite polar energies and so transcend maya and prakriti.

In the Hindu religion tantra yoga consists of two major approaches: the Dakshinachara Path (known as right-handed Tantra) and the Vamachara Path (known as left-handed Tantra). Right-handed tantra typically would only symbolically, and not actually, engage in the deeds of the flesh associated with its ritual. Left-handed tantra, on the other hand, not only involves actual sex, alcohol, and drugs, but also has been known to involve black magic and all kinds of debauchery and criminal acts, including child sacrifice.15

Hatha Yoga

Hatha yoga is physical yoga, and it is the variety of yoga that we most commonly encounter in the West. Indeed, many Westerners think of little else when they hear the word yoga. It is often promoted as a superior method of physical development with no religious ties necessarily attached, and on this basis it is the approach to yoga that has had the greatest success in penetrating both secular culture and the evangelical church.

Its classical textbook is the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, written in the fifteenth century A.D. by Svatmarama, a little-known Indian yogi. Its first three verses declare that the ignorant masses are not yet ready for the lofty raja yoga and so hatha yoga has been developed as a “staircase” to lead them to it.16

How does this “staircase” work? First, it is common for literature on hatha yoga originating from Hindu sources17 to emphasize that the purpose of the postures and breathing exercises is to “free the more subtle spiritual elements of the mind.” In other words, the physical exercises of yoga are intended to facilitate altered states of consciousness. They further are intended to foster “the development of will power, concentration, and self-withdrawal,” all necessary to “help you put your mind in a focused state to prepare for Meditation and, eventually, the search for enlightenment.” Finally, they are designed to “open the energy channels, which in turn allows spiritual energy to flow freely.”

Yogi Bhajan, a Sikh yoga teacher who was a major exponent of kundalini yoga in the United States until his death in 2004, affirmed that “the purpose of Hatha Yoga is to raise the awareness. It is a technology to bring the apana and prana, the moon and sun powers together to raise the consciousness. In other words, its stated aim is to raise the Kundalini. That is the purpose of Hatha Yoga. The difference from Kundalini Yoga is only a matter of time and rate of progress. The purpose of the two approaches is the same.”18

In chapters seven and eight of his coauthored book, The Spiritual Laws of Yoga, medical doctor and bestselling New Age Hindu author Deepak Chopra explains the wide-ranging spiritual purposes behind a variety of common hatha yoga poses. These include “energy-opening poses” such as the “spinal twist,” the “kneeling wheel,” the “diamond pose,” the “fish pose,” and the “child’s pose,” all of which are designed to open the chakras so that “vital energy is able to flow freely. The vital energy rising up through the spine is known as the awakening of the kundalini.”19

The question of whether yoga in general, and hatha yoga in particular, can be separated from their Hindu roots is where the rubber meets the road most directly for Christians. In parts two and three we will examine this issue in depth and we will also look at the leading yoga teachers and their distinctive brands of yoga, specific areas of Western culture where yoga has penetrated, and how Christians can and should respond to this major cultural development.

—Elliot Miller

NOTES

- For a thorough treatment of yoga’s history in the United States, see Elizabeth De Michelis, A History of Modern Yoga: Patanjali and Western Esotericism (London, New York: Continuum, 2004).

- Robert Love, “Fear of Yoga,” Columbia Journalism Review, November/December 2006, CJR, http://cjrarchives.org/issues/2006/6/Love.asp.

- In part two of this series we will examine specific examples of this.

- In the Yoga Sutras (2:40) Patanjali states that one of the effects of attaining purity is a disgust with the physical body and a disinclination to have sexual intercourse. This underscores a basic rejection in yoga of any inherent goodness in the physical world, despite the acclaimed physical benefits of yoga, and stands in sharp contrast to the biblical affirmation that creation (apart from the affects of sin on it) is “very good” (Gen. 1:31).

- M. Alan Kazlev, “The Shakta Theory of Chakras,” Kheper, http://www.kheper.net/topics/chakras/chakras-Shakta.htm.

- Transcendental Meditation is a form of yoga. It will not be discussed here, however, since it is not what people normally think of as yoga and since it was the subject of a two-part feature article in the Journal just a few years ago. See John Weldon, “Transcendental Meditation in the New Millennium (Part One: Is TM a Religion?),” Christian Research Journal 27, 5 (2004): 12–21 (http://wwequip.org/JAT262-1), and John Weldon, “Transcendental Meditation in the New Millennium (Part Two: Does TM Really Work?),” Christian Research Journal 27, 6 (2004): 24–33 (http://www.equip.org/JAT262-2).

- For more on this see Sri Swami Sivananda, “Jnana Yoga,” The Divine Life Society, http://www.dlshq.org/teachings/jnanayoga.htm.

- “The Four Paths of Hindu Yoga,” Bikram Yoga Products, http://www.bikramyogaproducts.com/information.php?info_id=7&osCsid=ba34fa78a7b57b541c94e9279dc3ef.

- Swami Vivekananda, The Complete Works of Swami Vivekanandaa, vol. 1, Raja-Yoga, “Introductory,” http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Complete_Works_of_Swami_Vivekananda/Volume_1/Raja-Yoga/Introductory.

- Ibid., “Dhyana and Samadhi,” http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Complete_Works_of_ Swami_Vivekananda/Volume_1/Raja-Yoga.

- Amma, “Dhyan-Yoga and Kundalini Yoga,” quoted in Charles S. J. White, “Swami Muktananda and the Enlightenment through Sakti-pat,” History of Religions 13, 4 (May, 1974): 318.

- Swami Vivekananda, “The Psychic Prana,” http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Complete_Works_of_Swami_Vivekananda/Volume_1/Raja-Yoga/The_Psychic_Prana. See also his comments about Muhammad in the section “Dhyana and Samadhi.”

- Gopi Krishna, an advocate of raising the kundalini, nonetheless vividly described how doing so unleashed for him seven years of severe psychological and spiritual disorders. (Pandit Gopi Krishna, Kundalini: Path to Higher Consciousness [New Delhi: Orient Paperbacks, 1992].) “He conceived of this energy as an intelligent force over which he had little control once it was ” (“Gopi Krishna: Sage of the Kundalini Energy,” Om-Guru, http://www.om-guru.com/html/saints/gopi.html.)

- Swami Nikhilananda, Hinduism: Its Meaning for the Liberation of the Spirit, 2nd ed., Sri Ramakrishna Math, 1982, as quoted in Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tantra#_ref-nikhilananda_2.

- See, e.g., John Lancaster, “India’sMystical Murders,” Washington Post, Nov. 25, 2003, A22, http://www.washingtonpost.com/ac2/wp-dyn/A11810-2003Nov24?language =printer.

- Svatmarama, The Hatha Yoga Pradipika, The Sacred Books of the Hindus, e Major Basu, I.M.S. (retired) (Bahadurganj, Allahabad: Sudhindranatah Vasu, 1915), http://www.geocities.com/kriyadc/hatha_yoga_pradipika_chapter1.html.

- See, e.g., “Hatha Yoga: The Yoga of Postures,” ABC of Yoga.com, http://www.abc-of-yoga.com/styles-of-yoga/hatha-yoga.asp, from which all of the quotes in this paragraph are drawn.

- Kundalini Yoga as Taught by Yogi Bhajan, comp. Datta Singh, http://www.goldenbridgeyoga.com/uploads/pdf/Beginners_Guide.pdf.

- Deepak Chopra and David Simon, The Seven Spiritual Laws of Yoga: A Practical Guide to Healing Body, Mind, and Spirit (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, 2004), 176.