Cultural Apologetics Column

The following article was an Online-exclusive.

When you to subscribe to the Journal, you join the team of print subscribers whose paid subscriptions help provide the resources at equip.org that minister to people worldwide. These resources include our ever growing database of over 1,500 articles, as well as our free Postmodern Realities podcast.

Another way you can support our online articles is by leaving us a tip. A tip is just a small amount, like $3, $5, or $10 which is the cost for some of a latte, lunch out, or coffee drink. To leave a tip, click here

Television Series Review

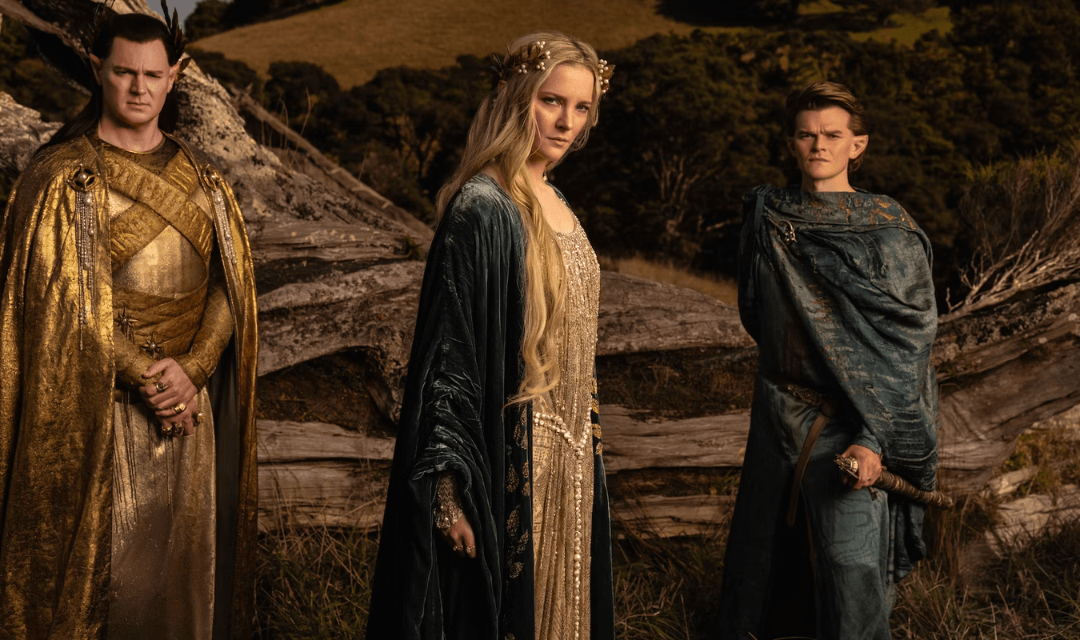

The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power

Developed by J. D. Payne and Patrick McKay

Executive Producers: J. D. Payne, Patrick McKay, Christina Morgan, Lindsey Weber, Callum Greene, Justin Doble,

Gennifer Hutchison, Jason Cahill, J. A. Bayona, Belén Atienza, Eugene Kelly, Bruce Richmond, and Sharon Tal Yguado

Producers: Ron Ames and Chris Newman

Streaming on Amazon Prime Video

(Rated TV-14, 2022—)

**Editor’s Note: This article contains spoilers for The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power.**

For many years, J. R. R. Tolkien’s legendarium was considered “unfilmable.”1 Then along came film director Peter Jackson with producing partners Fran Walsh and Barrie M. Osborne, and together they crafted a film trilogy adaptation of Tolkien’s most popular work. The Lord of the Rings trilogy grossed nearly three billion dollars worldwide and won seventeen Academy Awards — with the third film of the trilogy nabbing Best Picture in 2003. With a nearly $300 million budget, this series remains one of the most expensive and ambitious film productions.

Despite its success, the film series has not been without its detractors. Among its most notable critics was Tolkien’s own son, Christopher, who claimed that Jackson eviscerated the source material to make an action film.2 Christopher’s words seemed to echo his father’s own concerns regarding the adaptability of the world he had created.3

In November of 2017, Amazon secured the rights for The Lord of the Rings from the Tolkien estate, promising to resurrect the dormant series and adhere even more faithfully to Tolkien’s source material, even bringing in Tolkien’s grandson, Simon, during the development process. The culmination of Amazon’s acquisition of the prestigious property arrived in September 2022, as the first episodes of a proposed five season television series titled The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power, a prequel to Tolkien’s trilogy and Jackson’s subsequent film adaptations, though the series stands alone and separate from the continuity of Jackson’s films.

Despite some criticism, The Rings of Power has received scores of positive reviews aimed at its cinematography and visual effects — as well it should, considering that it is the most expensive television series ever produced, with nearly $500 million being thrown at the first season alone.4 But the question of whether the series honors Tolkien’s legacy and his vision for the fantasy world he created prompts a discussion of another kind.

The Second Age. From an objective standpoint, the decision to focus The Rings of Power on a time separate from the one covered during the events of The Lord of the Rings makes a certain amount of sense. Jackson’s film series is such a well-known, successful, and recent adaptation, that to try to replicate that story would be tantamount to trying to remake the original Star Wars trilogy — it simply would not work, as the material is too beloved by too many people still living. Thus, the decision was made to locate the narrative of the series in the Second Age of Tolkien’s fictional “Middle-Earth,” a time before the Third Age depicted in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings.

Yet the decision is also a curious one, considering that Amazon acquired the rights only to The Lord of the Rings. The rights to Tolkien’s primary text depicting events occurring in the Second Age, a dense but stunningly original work titled The Silmarillion, remain with his estate. Thus, the showrunners are forced to adapt material depicted in The Silmarillion but taken from the appendices of Tolkien’s popular trilogy. Though this might seem like a technicality, this nuance is an important one for understanding the development process; The Rings of Power is an adaptation of one, but not the other. The series carries the title of The Lord of the Rings, not The Silmarillion.

The story of The Rings of Power concerns itself with a multitude of disparate but overlapping story threads — the Harfoots (a kind of hobbit in Middle-Earth) and their encounter with a mysterious entity wielding considerable magical powers, the series-exclusive characters Arondir (Ismael Cruz Córdova) and Bronwyn (Nazanin Boniadi) and their forbidden love affair, Galadriel (Morfydd Clark) and her search for one of Morgoth’s lieutenants named Sauron, and Elrond (Robert Aramayo) and his working relationship with master smith Celebrimbor (Charles Edwards), as well as his friendship with Prince Durin (Owain Arthur). The narrative culminates with the creation of the first three titular rings at the hands of Celebrimbor under the subtle influence of a deceptive Sauron.

The series follows Tolkien’s template in broad strokes, though certain key events that in the legendarium are separated by hundreds of years, are here condensed into a much tighter timeframe. In the grand scheme of things, playing with Tolkien’s timeline in such a way is hardly a grievous offense; in fact, despite the condensed timelines, one of the biggest complaints about the series has been its pacing, which many have deemed as moving too slowly.5 One hesitates even to classify these kinds of adjustments as “changes” in the true sense of the word, as nothing in them outright contradicts Tolkien’s established lore. These are minor alterations for the sake of adaptation, and the creatives have repeatedly made clear that their decisions are measured and calculated, the result of a careful reading of the texts to which they have adaptation rights.6

The Heart of the Story. While there is certainly no accounting for individual tastes, some of the criticisms directed at The Rings of Power seem remarkably shortsighted. In fact, several of the narrative threads would indicate that the showrunners have a better understanding of what Tolkien himself considered the core ideas of The Lord of the Rings than many critics.

In a 1957 letter to Herbert Schiro, Tolkien wrote: “I should say, if asked, the tale is not really about Power and Dominion: that only sets the wheels going; it is about Death and the desire for deathlessness.”7 A year later, in a separate letter, he would note that the series “is mainly concerned with Death, and Immortality; and the ‘escapes’: serial longevity, and hoarding memory.”8 These core ideas, which the author himself attributes to the series, are reflected quite profoundly in The Rings of Power. The Elves fear the death of their kind, prompting Elrond to turn to the Dwarves for help. Galadriel is haunted by and driven to avenge the death of her brother, Finrod (Will Fletcher). Fear of the unknown and the potential death it brings cripples and emotionally stunts the Harfoots, so that they, as a group, would turn their backs on a stranger in need were it not for the bold and fearless Nori (Markella Kavenagh), and a critical component of their culture revolves around “remembering” those Harfoots who were left behind during the migrations of their caravans.

While The Rings of Power takes certain liberties with Tolkien’s timeline, the themes at play throughout the series — from the conflict between good and evil, to the attempts made to maintain the longevity of life — would seem to walk in lockstep with Tolkien’s analysis of his own work.

The Dark Lord. Of all the adjustments made, there is only one that can be safely claimed as a true change from the source material, and that would be how The Rings of Power handles the great villain of the series, Sauron. The series kicks off in the Second Age, after Morgoth’s defeat, during the time in which Sauron lingers in Middle-Earth, biding his time until his return to power. According to Tolkien’s lore, Sauron eventually comes to befriend Celebrimbor under the persona of an elf named Annatar, who puts Celebrimbor on the path to forging the titular rings of power. However, the twist at the conclusion of the first season of The Rings of Power reveals that Sauron is disguised in Middle-Earth as a slippery human named Halbrand (Charlie Vickers), who first encounters and comes to know Galadriel, and it is through Halband and his relationship to Galadriel that he seemingly allies himself with Celebrimbor.

Now, it is entirely possible that Sauron, who is last seen entering the land of Mordor under the guise of Halbrand, will return as Annatar to continue his deception of the Elven smiths in later seasons. But as it stands, the details here play fast and loose with this aspect of Tolkien’s canon, though the concept of Sauron disguising himself to deceive Celebrimbor long enough to inform his crafting of the legendary rings remains in place.

Sauron as Halbrand takes from Celebrimbor’s story in Tolkien’s legendarium but adds to Galadriel’s arc in the series. Positioning Sauron under her nose, slowly gaining her trust, when her journey revolves around hunting down the junta still loyal to Morgoth, is an ironic twist that provides a fascinating commentary on her temptation when she encounters the One Ring in The Lord of the Rings — a truly terrifying scene that plays out in Jackson’s adaptation of The Fellowship of the Ring (2001).

Evil and Faith. In The Rings of Power, several of its characters, including Halbrand, visit Númenor, the fabled island kingdom of men. Not only does Sauron, the cunning deceiver, exert his influence over Celebrimbor in Tolkien’s legendarium, but his temptation of the Númenoreans regarding eternal life leads to the eventual destruction of their city and their people — a vision that is glimpsed by both Galadriel and Tar-Míriel (Cynthia Addai-Robinson) in The Rings of Power, certainly foreshadowing the drama to come in future seasons. In Tolkien’s work, the destruction of Númenor leads to the founding of Gondor and the alliance of Elves and men that battles Sauron at the end of the Second Age (the prologue depicted in Jackson’s film series), which is almost certainly the event that will conclude The Rings of Power.

Paul D. Miller, writing for Christianity Today, points to the story of Númenor’s downfall as a kind of cautionary tale that still bears significance for us today, as political divisions threaten to tear America asunder and fragment the church along with it.9 But it would be unwise to judge The Rings of Power on a story that it has only hinted at and yet to actually tell; there is as much room for the series to fail this story as there is for it to fully realize Tolkien’s legacy. That being said, thus far The Rings of Power seems content relishing the quieter moments, such as the meals shared between Elrond and Durin and Durin’s wife, Disa (Sophia Nomvete), as much as it doubles down on the scenes containing big action spectacles, such as the forming of Mount Doom.

In this way, the showrunners at least demonstrate an appreciation for the power of simple, ordinary goodness that is the beating heart of Tolkien’s world, even if they do not fully understand it. Tolkien himself described The Lord of the Rings as a “fundamentally religious” story, and there is no denying that Tolkien’s faith is part and parcel of his legendarium.10 What sets Tolkien’s fantasy apart from so many others today is its clear sense of right and wrong, of good and evil firmly rooted in a well-developed Christian imagination that was capable of wrestling with difficult subjects, such as death, without compromise. It takes a mature faith to recognize that Frodo, due to the great darkness he experienced bearing the weight of the One Ring, could not remain in Middle-Earth and find contentment, just as it takes a mature faith to recognize that the answer to great and terrible evil is not a great and powerful goodness, but ordinary goodness, the kind that disarms evil and strips it of its power rather than seeking to destroy it — a lesson that Galadriel herself seems to be learning in The Rings of Power.

It is too soon to say whether The Rings of Power is worthy of the title it carries. But if the question is whether the Christian should tune into House of the Dragon (HBOMax, 2022–) or The Rings of Power, well, that is a no-brainer. If nothing else, there is something to be said for the fact that a series written by a Christian is now the biggest television series produced to date. That the showrunners are not moving to excise the author’s faith or convictions from the screen but desire to lean into the source material to craft their adaptation is a testament to the power of Tolkien’s story and the power of a Christian imagination.

Who knows where Amazon will take The Rings of Power over the next four seasons? But it would be a shame — even immature — for people of faith to jump ship now over a few adjustments to Tolkien’s timeline. —Cole Burgett

Cole Burgett is a graduate of Dallas Theological Seminary and the Moody Bible Institute. He teaches classes in systematic theology and Bible exposition and writes extensively about theology and popular culture.

NOTES

- Jim Vorel, “Peter Jackson’s LOTR Was an Improbable Miracle, and We’re Lucky to Have It,” Paste Magazine, December 17, 2021, https://www.pastemagazine.com/articles/2020/03/peter-jacksons-lotr-was-an-improbable-miracle-and.html.

- Christopher Tolkin, quoted in Raphaēlle Rérolle, “Tolkien, l’anneau de la discorde,” Le Monde, July 5, 2012, https://www.lemonde.fr/culture/article/2012/07/05/tolkien-l-anneau-de-la-discorde_1729858_3246.html.

- Humphrey Carpenter (Tolkien’s official biographer), quoted in Patrick Lyon, “How Accurate Is ‘The Rings of Power’ from a Tolkien Book Fan Perspective?” Collider, September 14, 2022, https://collider.com/rings-of-power-book-reader-analysis-criticism/.

- Travis Clark, “‘The Rings of Power’ Isn’t Just a TV Show for Amazon — It’s Another Way for the Company to Dominate Every Aspect of Your Life,” Business Insider, September 7, 2022, https://www.businessinsider.com/rings-of-power-more-than-a-tv-show-for-amazon-2022-9.

- Nick Bythrow, “The Rings of Power Showrunner Address Pacing Criticisms,” Screenrant, October 8, 2022, https://screenrant.com/rings-power-pacing-criticisms-showrunner-response/.

- Jackson McHenry, “Close-Reading Lord of the Rings with the Creatives Behind The Rings of Power,” Vulture, August 30, 2022, https://www.vulture.com/article/lord-of-the-rings-the-rings-of-power-plot-explained.html.

- J. R. R. Tolkien, quoted in Humphrey Carpenter, “#203 to Herbert Schiro, 17 November 1957,” in The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1981).

- J. R. R. Tolkien, quoted in Humphrey Carpter, “#211 to Rhona Beare, 14 October 1958,” in The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1981).

- Paul D. Miller, “A Moral Primer on Amazon’s ‘Rings of Power,’” Christianity Today, September 1, 2022, https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2022/august-web-only/rings-of-power-lord-of-rings-jrr-tolkien-primer.html.

- J. R. R. Tolkien, quoted in Humphrey Carpter, “#142 to Robert Murray, S. J., 2 December 1953,” in The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1981).