Cultural Apologetics Column

The following article appeared as an online-exclusive in CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL, volume 48, number 03 (2025).

When you support the Journal, you join the team and help provide the resources at equip.org that minister to people worldwide. These resources include our ever-growing database of more than 2,500 articles and Bible Answers, as well as our free Postmodern Realities podcast.

Another way you can support our online articles is by leaving us a tip. A tip is just a small amount, like $3, $5, or $10, which is the cost of a latte, lunch out, or coffee drink. To leave a tip, click here.

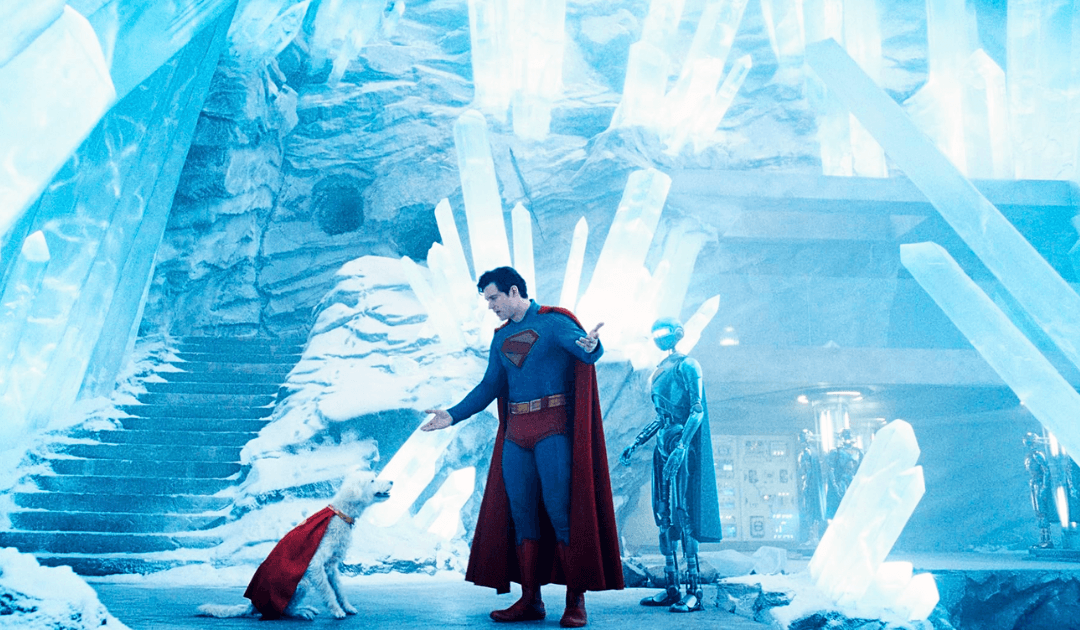

[Editor’s Note: This review contains spoilers for Superman (2025).]

Superman

Directed by James Gunn

Written by James Gunn

Produced by Peter Safran and James Gunn

Starring David Corenswet, Rachel Brosnahan, Nicholas Hoult, Edi Gathegi, Anthony Carrigan, Nathion Fillion, and Isabela Merced

Feature Film (PG–13)

(Warner Bros. Pictures, 2025)

Superman shouldn’t be controversial. And yet the Man of Steel once again finds himself at the center of public debate — not because of some bold new direction for the character, but simply for showing up in the first place. The release of James Gunn’s Superman (2025) has reignited cultural conversations about what this character represents, why he endures, and whether there’s still a place in the modern world for a hero defined by virtue and, most importantly, restraint.

Created in 1938 by two sons of Jewish immigrants, Superman was born out of the anxieties of a world on the brink of war.1 He was a kind of immigrant himself — rocketed from a dying planet and raised in the heartland of America, a messianic figure in colorful red and blue who defended the weak and reminded readers of a heroic ideal worth aspiring to. For generations, he stood as the moral center of the superhero genre: powerful, yes, but also principled, self-sacrificial, and above all, good.

But in recent years, Superman has become oddly polarizing.2 Some view him as outdated, a relic of a simpler time whose unwavering code of ethics feels naïve against the “moral gray” of the modern world.3 Others bristle at how he’s portrayed on screen, whether too brooding or too bright, too distant or too human.4 With this new Superman film — which also has the gargantuan task of launching DC Studios’ new Marvel-esque “shared universe,” the DC Universe (DCU) — Gunn seeks to introduce the character not with the usual irony that is so characteristic of modern films, or with the deconstructive approach favored by Zack Snyder that was a hallmark of early twenty-first century filmmaking, but with sincerity.

American Mythology. Superman is not just any old superhero — he is the superhero, the archetype from which all others are drawn. Yes, there were many proto-superheroes that inspired the likes of Superman, but Big Blue was the character that came along and codified in the popular imagination the tropes that go into making a comic book superhero a superhero.5 In him, Depression-era America found both an escape and a kind of secular savior — an incorruptible being of immense power with not-so-subtle messianic undertones, who chose not to rule, but to serve. He was faster than a speeding bullet, yes, but also gentler than most men. And it’s in that restraint, that commitment to use his power to benefit others, that he became a kind of symbol, one that embodied virtue and authority without the weight of the cynicism that was creeping into a culture increasingly skeptical of such things. Even if Siegel and Shuster did not set out to overtly write a Christ figure, in drawing deeply from the well of Western culture’s moral imagination (and probably some Jewish messianic expectations), they gave us one anyway.6

In this light, Gunn’s Superman is uniquely positioned within a cultural moment in which a younger generation — shaped more by irony than by ideals, per se — might rediscover the longing for a hero who doesn’t so much reflect our fractured world as gently, and powerfully, transcend it. This take on Superman has been described as something of a Saturday morning cartoon, and that is a fairly accurate assessment.7 The film introduces us to a world that is like our own but is not quite our own. It assumes that viewers come into the world of the film understanding that superheroes exist. It’s not a strange thing for Superman (David Corenswet) to interact with the Green Lantern (Nathan Fillion), for example, and Green Lantern needs no explanation or backstory. He, like other “metahumans,” is simply there, and everyone knows who he is. And all of this is very intentional. In an interview with Entertainment Weekly, Gunn himself stated, “I grew up reading DC and Marvel comics and having worlds and universes of superheroes who were interacting. I grew up watching Super Friends on Saturday mornings.”8

What emerges, then, is arguably Gunn’s most sincere film to date. Though his fingerprints are all over this piece — the characteristic humor, the offbeat supporting cast, and the lived-in weirdness that has become his hallmark — Superman marks a clear departure from the biting cynicism and gleeful irreverence of The Suicide Squad (2021) or Peacemaker (2022–present). Toned down is the impulse to deflate every emotional beat with a wink to the audience. Instead, Gunn leans into a tone that feels unabashedly heartfelt, embracing the idea that Superman can still be noble without being boring, that kindness is not weakness, and that goodness can, in fact, be dramatically compelling.

This tonal shift feels deliberate, not just stylistically, but thematically. Gunn, who built his career telling stories about misfits, losers, antiheroes, the down-and-outs, is now telling a story about the opposite: a man who is almost too good, too powerful, too decent. And rather than try to drag that character down into the dirt to “make him relatable,” Gunn seems more interested in showing us why that ideal still matters — why, in an age that distrusts power and deconstructs every institution, the image of a man who could do anything but chooses to do what’s right remains both necessary and inspiring.

There is a quiet sort of challenge baked into this version of Superman. Not to believe in a perfect hero, but to believe that goodness — flawed, human — is still possible. That it still has a place in the modern imagination. And in that way, Gunn’s Superman is less so much a course correction for a cinematic universe, and much more of a “cultural reset” that seeks to remind audiences increasingly jaded toward the obligatory superhero blockbuster that true heroism begins not with power, but with character.

Refreshingly, Gunn’s approach isn’t interested in rehashing the internet’s favorite schoolyard debate: “Who would win in a fight, Superman or X?” That conversation, while perhaps fun for forums and fanboys, has long distracted from the deeper appeal of the character. Superman establishes from its very first moments that Superman is, unequivocally, the most powerful metahuman on Earth. There’s no mystery to it. There’s no need to “scale” his strength. He can fly, he can lift, he can burn through steel with a glance. But Gunn isn’t concerned with power levels — he’s concerned with character. It’s never been Superman’s power that makes him compelling. It’s the fact that he chooses not to use that power selfishly, destructively, or opportunistically. It’s the fact that he can be hurt, not just physically (though it’s tough to do), but emotionally. That he feels deeply. That he wrestles with questions of identity, with the tension of belonging everywhere and nowhere all at once. And yet he still shows up. In this film, Superman’s strength is a given. His goodness is the story.

What’s There to Talk About? It’s interesting that Gunn played a big role in helping to overstuff the current cinematic landscape with quippy superheroes. Because with Superman, he offers up something different and a bit unexpected: a serious moral imagination clothed in primary colors. It’s not a Christian film, of course. It doesn’t gesture toward religious systems. In fact, Gunn seems to avoid playing up the Superman-as-Jesus imagery that Zack Snyder mined for his take on the character.9 Nevertheless, it does what good mythology has always done — awaken the moral senses. It invites the viewer to imagine a world in which power is not wielded for self-gain but for the good of others, which is why Nicholas Hoult’s morally bankrupt Lex Luthor is the perfect antagonist here. It stirs longing for a kind of goodness that is both effective and right. And that, for the Christian apologist, is fertile ground.

In cultural apologetics, we often go looking for desires. We look for those moments when art or story exposes the cracks in the secular imagination — where audiences, sometimes despite themselves, find their hearts moved by ideals they’ve been conditioned to distrust. Superman does exactly this. It’s a film that believes in virtue without irony. It takes seriously the idea that power can serve rather than corrupt and dares to suggest that restraint is more impressive than domination.

This makes Superman an accessible on-ramp to more important questions. Why do we resonate with stories of sacrifice and moral clarity? Why are we drawn to a character like Superman, who could destroy but chooses to protect? Why does his compassion move us more than his strength? These are not just aesthetic questions, and they open the door to a gospel conversation not by mimicking the gospel directly, but by creating space for its categories to make sense. Superman doesn’t need to be a Christ figure in the explicit sense to point beyond himself. His story, especially as told here, dignifies the giving of oneself for the sake of others. It insists, however quietly, that there is something in us that still longs for goodness not as a punchline, but as a genuine possibility.

Cole Burgett is a graduate of Dallas Theological Seminary and the Moody Bible Institute. He teaches classes in systematic theology and Bible exposition and writes extensively about theology and popular culture.

NOTES

- For those interested in the history of pop culture’s most iconic superhero, I highly recommend Edward Gross and Robert Greenberger, Superman: The Definitive History (Insight Editions, 2024). This massive 400+ page deep dive into the Man of Steel’s century-long legacy features interviews with writers and artists (and makes a great coffee table piece).

- James Gunn — perhaps unwisely — brought his own film under even closer public scrutiny when stating that “Superman is an immigrant,” which really shouldn’t be a bizarre thing to assert, considering the Man of Steel’s well-known origin story. But given the current political climate in America, this comment was sure to take on layers of different meanings for different folks — and that’s exactly what has occurred. See James Gunn, quoted in Jack Dunn and Marc Malkin, “James Gunn, Nathan Fillion, and More on MAGA Outrage Over Director Saying Superman Is an Immigrant: ‘I Don’t Have Anything to Say to Anybody’ Spreading Hate,” Variety, July 7, 2025, https://variety.com/2025/film/news/james-gunn-superman-immigrant-backlash-response-1236449068/.

- See Christopher Dibsdall, “Superman: Too Perfect for the Modern World?,” The Artifice, June 21, 2013, https://the-artifice.com/superman-too-perfect-for-the-modern-world/.

- For a good analysis of the cultural conversation surrounding the best-known portrayal of Superman from the last decade, see J. C. Macek III, “Reboot to the Head: A Comicbook-Based Analysis of Zack Snyder’s Man of Steel,” PopMatters, July 10, 2013, https://www.popmatters.com/173387-reboot-to-the-head-a-comicbook-based-analysis-of-snyders-man-of-stee-2495741238.html.

- There are a few different threads one can run down when debating the “origins” of superheroes. In a sense, these kinds of characters have always been with us, codified in myths and legends throughout history (think Gilgamesh, Heracles, Robin Hood, etc.). However, the comic book superhero is a distinctly American-flavored take on the heroic figure archetype that emerged in the early twentieth century in the funny pages and radio serials (think colorful costumes, secret identities, etc.). Some of the direct precursors to Superman are some of my favorite characters ever created — though many are largely forgotten today: Buck Rogers (created by Philip Francis Nowlan), The Shadow (created by Walter B. Gibson), Doc Savage (created by Kenneth Robeson), Flash Gordon (created by Alex Raymond), and The Phantom (created by Lee Falk).

- Much ink has been (and will undoubtedly continue to be) spilled when discussing the development of Superman’s messianic identity. See Deepa Bharath and Bob Smietana, “Is He Christ? Is He Moses? Superman’s Religious and Ethical Undertones Add to His Mystique,” The Land, April 19, 2025, https://thelandcle.org/stories/is-he-christ-is-he-moses-supermans-religious-and-ethical-undertones-add-to-his-mystique/.

- See Jared Rasic, “New ‘Superman’ Flick Bodes Well for James Gunn’s DC Universe,” Detroit Metro News, July 14, 2025, https://www.metrotimes.com/arts/new-superman-flick-bodes-well-for-james-gunns-dc-universe-39942330.

- James Gunn, quoted in Nick Romano, “Superman Lights the Way: How Hollywood’s New Man of Steel Shepherds the DC Universe of Tomorrow (Exclusive),” Entertainment Weekly, June 10, 2025, https://ew.com/superman-new-man-of-steel-leads-dcu-of-tomorrow-cover-story-11751060.

- See Snyder’s comments on the messianic imagery in his Man of Steel (2013) in Jennifer Vineyard, “‘Man of Steel’ Director Zack Snyder on Superman’s Christ-like Parallels,” CNN, June 16, 2013, https://www.cnn.com/2013/06/14/showbiz/zack-snyder-man-of-steel.