Listen to this article (14:17 min)

Cultural Apologetics Column

The following article appeared as an online-exclusive in CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL, volume 48, number 02 (2025).

When you support the Journal, you join the team and help provide the resources at equip.org that minister to people worldwide. These resources include our ever-growing database of more than 2,500 articles and Bible Answers, as well as our free Postmodern Realities podcast.

Another way you can support our online articles is by leaving us a tip. A tip is just a small amount, like $3, $5, or $10, which is the cost of a latte, lunch out, or coffee drink. To leave a tip, click here.

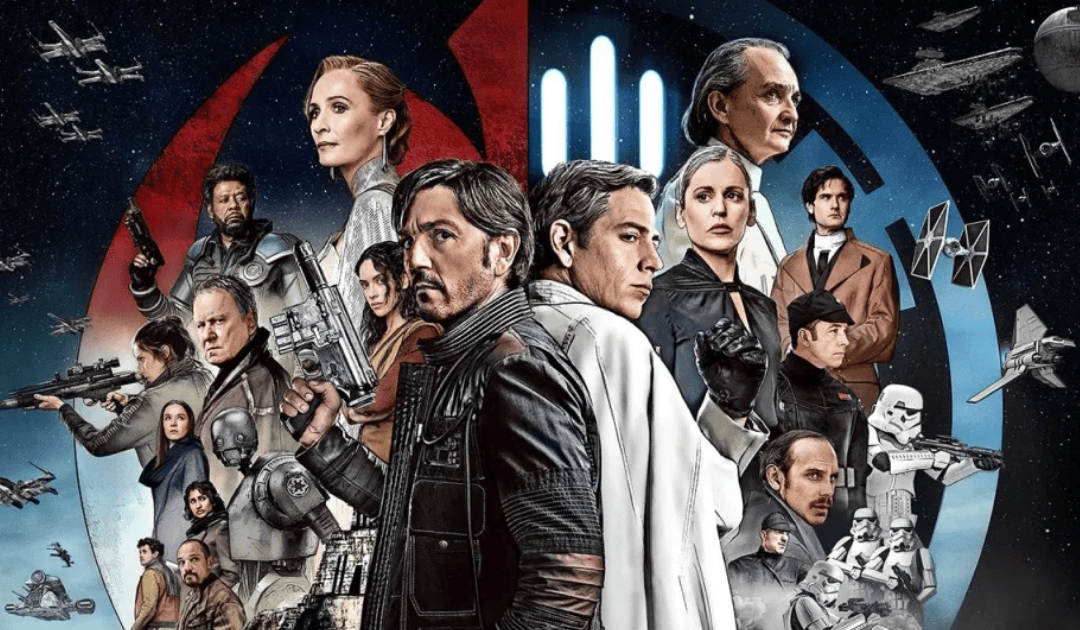

[Editor’s Note: This review contains spoilers for Star Wars: Andor.]

Star Wars: Andor

Created by Tony Gilroy

Executive Producers: Sanne Wohlenberg, Tony Gilroy, Kathleen Kennedy, Diego Luna, Toby Haynes, Michelle Rejwan, John Gilroy, and Luke Hull

Producers: Kate Hazell and David Meanti

Lucasfilm

2022–2025, TV–14

Streaming on Disney Plus

Reviewed by Cole Burgett

It goes without question that Star Wars: Andor (2022–2025) is some of the finest television produced in recent years. It’s the kind of show that lingers in the mind long after the credits roll — morally complex, brilliantly acted, and suffused with a quiet, creeping tension that rarely lets up.1 And yet, for all its quality, there’s something unmistakably off in the show’s second (and final) season. Not in the execution, but in the context. Because for all its strengths, Andor feels less like a new chapter in Star Wars and more like a foreign novel translated into its language.

This isn’t unique to the second season, but it becomes more prominent here and harder to ignore. That’s because this season begins to pull more aggressively toward the franchise spine: syncing up with Rogue One: A Star Wars Story (2016), which in turn presses up tightly against Star Wars: A New Hope (1977). The closer Andor moves toward the narrative center of Star Wars, the more glaring its thematic dissonance becomes.

This isn’t merely about tone. It’s not just that Andor is “darker” or “grittier” or more talkative than the films that came before it. Rather, it operates within an entirely different moral and mythological framework. Where Star Wars has always embraced its operatic roots — its chosen ones, its mysticism, its clean divisions between light and dark — Andor thrives in ambiguity. It sees heroism not as destiny but as compromise, and rebellion less as a moral crusade and more as a slow, grinding machinery of sacrifice.

In doing so, Andor becomes something extraordinary — but also something alien. It stretches that galaxy far, far away into a territory of space that it was never built to hold. And that stretch inadvertently reveals some of the central dilemmas of modern franchise storytelling: how far can intellectual property bend before it breaks? At what point does telling a better story mean telling a different one entirely?

The tension between form and foundation is not only a problem for Hollywood but also indicative of a wider cultural dilemma. Can any story once untethered from the originating worldview remain coherent? And here the conversation steps more broadly into the realm of cultural apologetics — because Andor and Lucas’s Star Wars tell stories built on different metaphysical and ethical assumptions.2 Star Wars is a myth with redemption as its focus. It believes in destiny, in the possibility of forgiveness, and that the “moral arc” of the universe (and, indeed, a cosmic “Force”) bends toward something that resembles goodness. It is a universe shaped, however loosely, around good and evil in an absolute sense.

Andor, by contrast, offers a world without transcendence. Its characters live in a closed system — one governed by Orwellian power, compromise, and incremental change. There is no Force guiding anything, only people clawing for meaning amid bureaucracy and moral erosion. That’s not a flaw in Andor — it’s the point.3 But it means viewers are watching two entirely different moral visions trying to occupy the same narrative space.

Cultural apologetics must reckon with the phenomenon of stories that borrow the aesthetics and language of a theistic worldview but are increasingly written from an entirely secular imagination. Andor is what happens when a story is told in the trappings of Star Wars but with the transcendent moral architecture that makes Star Wars what it is stripped out. It’s coherent, powerful, emotional — but it no longer points upward. It no longer has any reason to believe in destiny, only necessity.

This is where viewers must learn to read culture not just for quality but for direction. It is not enough to ask, Is this good art? The question must broaden. What kind of world does this story assume — and does it align with what is true? In the case of Andor, it may be good art with sharp acting and excellent writing, but it is also a story built entirely within the confines of a world that has forgotten transcendence. That does not make it unwatchable — but it does make it incoherent when plugged into a mythos originally crafted to echo some kind of cosmic redemption story.4

So Andor becomes a case study — not in what’s wrong with Star Wars but in what happens when a narrative shell is inherited without the worldview that originally gave it meaning. And that raises the urgently pertinent question of how one is to address a culture fluent in the language of transcendence yet lacking a firm grasp of its semantics and grammar.

Rebellion Without Revelation. Andor is Star Wars reinterpreted through the assumptions of modern secularism — a shift in the metaphysics of the thing. The show attempts to reimagine a fundamentally mythic universe using the tools of political realism. The result is something that is intellectually serious and emotionally rich but, ultimately, mythically hollow.

And it shows — most clearly when the show tries to retrofit itself into the machinery of Rogue One and, by extension, A New Hope. Because suddenly viewers are meant to believe that Luthen’s cold calculus, Bix’s suffering, and Kino Loy’s agonizing sacrifice all funnel neatly into Luke Skywalker’s zero-hesitation destruction of the Death Star — an act that Andor would portray as a necessary evil, while A New Hope (and its sequels) treats it as a clean victory. There is no reckoning, no soul-searching, no moral cost. Andor builds a world in which choice scars, whereas Star Wars has always suggested that simple belief can heal.5

That dissonance matters. Because Andor is reframing the rebellion that forms the backbone of the original trilogy. Hope, which is a topic of conversation in the second season of Andor (and Rogue One) is less a virtue than it is manufactured propaganda that just runs in a direction opposite that of the Empire. Even Cassian (Diego Luna) himself is somewhat reimagined here, not as the wide-eyed and conflicted agent of destiny we see in Rogue One but as a reluctant insurgent pressed into action by something close to moral exhaustion. The rebellion is meaningful here, but it is not mythic.

And that matters both for the story being told and the viewer’s response to it. Because if the response to Andor shows us anything, it’s the subset of audiences who prefer stories without transcendence, where meaning is constructed and not revealed. Andor doesn’t “accidentally” forget the Force — it deliberately excludes it, at least for a time. It is reintroduced more prominently in the second season via a healer (Josie Walker), though that character is hardly presented as anything resembling a Jedi, bearing more in common with a fortune teller than anything else.6

So, perhaps it is a misnomer to say that Andor completely abandons the transcendent — it does, however, recontextualize it. When belief surfaces, it does so cautiously, often from the mouths of secondary characters, holdouts whose convictions are tolerated but rarely shared by the protagonists. When the Force appears in this series, it’s stripped of its Jedi framing and treated more like a cultural artifact, a belief system surviving in the cracks, more folklore and superstition than faith.

This is not the language of Lucas’s Star Wars. This is something more anthropological — less a spiritual truth than a window into what desperate people need to believe in. And in this way, Andor becomes a kind of internal counter-argument, a reply. Where Lucas’s original vision for Star Wars remains unwavering, Gilroy’s Andor interrogates those assumptions. This is what makes Andor both so compelling and so disruptive. It is, even more so than Rian Johnson’s 2017 film, The Last Jedi, the first Star Wars story to talk back. And it shows us just how far Star Wars has drifted since 1977.

Because that original film is earnest to the point of being unfashionable. It believes in the underdog, in clear-cut evil, in heroes who can be trusted, in scoundrels who change because the right is, very simply, the right thing, and in a grander spiritual reality that ultimately guides the course of events. It is quite unconcerned with moral ambiguity. It never asks what the rebellion’s propaganda looks like. It doesn’t care about Mon Mothma’s bank accounts or the backroom deals that keep revolution afloat.

The Cultural Trajectory. Nearly fifty years since that original film, the current state of the Star Wars franchise reflects the world it inhabits. Though the series began in the late-twentieth century, it very intentionally channeled older types of storytelling.7 Now, however, the moral binaries that once guided the narrative have blurred into gray fields of strategic necessity. Even Luke Skywalker, the franchise’s moral compass, has been reimagined in recent films as broken and jaded. And so Andor is not just an outlier — but the logical end of a long arc. It is the product of a cultural moment that no longer knows what to do with myth, except to deconstruct it.

It’s no accident that Andor speaks so powerfully to the modern viewer when we have spent decades sanding the edges off the stories we once believed in — recontextualizing them, reframing them, retelling them until they say something different. Andor does not outright mock the Star Wars of old, but it does subtly imply that the old beliefs were a little naïve. This is the pattern of our age: secular culture does not so much discard myth and wonder as appropriate them — dressing them up in irony and realism, preserving their silhouette while draining them of rich epistemological and metaphysical substance. We dare not trust a story that asks us to believe in anything we cannot touch.

In such a world, Andor feels true. Its moral weariness speaks to us and tells us what we already suspect: that all institutions are compromised, that all revolutions are paid in blood, and that all belief is really about power.

The sort of storytelling Lucas relied on to create Star Wars is increasingly rare. Not because it’s unsophisticated, but because our culture has taught us to conflate sincerity with simplicity. The modern person is haunted by the suspicion that reality is something one must not be caught believing in. Because to believe in something grander than oneself (i.e., an invisible God) is to risk looking foolish. And in the economy of modern prestige television, foolishness is a sin not easily forgiven.

So, yes, Andor may give fuel to the fire of the cynic. It may confirm the suspicion that hope without caveat is sentimentality, that the Force is folklore, and that every rebellion is the result of compromise. But the Christian must resist the urge to nod along too easily. Not because those things aren’t partially true — but because they are not the whole truth. Realism is not reality — it is a certain point of view.

What Andor offers is a galaxy starved for grace. And that is where the Christian imagination has something better to say — not in opposition to Andor but beyond it. We can affirm its excellence, acknowledging its critique, and still say there is more to the story.

—Cole Burgett

Cole Burgett is a graduate of Dallas Theological Seminary and the Moody Bible Institute. He teaches classes in systematic theology and Bible exposition and writes extensively about theology and popular culture.

NOTES

- For additional context, see my review of the first season: Cole Burgett, “An Occasion for Just War: A Review of Andor,” Christian Research Journal 45, no. 03/04, 2022, https://www.equip.org/articles/an-occasion-for-just-war-a-review-of-andor/.

- As early as 1977, Lucas is quoted as saying that Star Wars was born out of a concern that “a whole generation was growing up without fairytales,” and was the result of his desire “to make a children’s movie.” This helps us to understand the reason for the relatively simplistic “moral structure” of the original films — it was, in fact, intentional. See Stephen Zito, “George Lucas Goes Far Out,” American Film (April 1977): 8–13. Archive scans of this article may be viewed via Berkeley’s Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive here: https://cinefiles.bampfa.berkeley.edu/catalog/29121.

- Several critics have highlighted this in reviews of Andor. One of them is Derek Pharr, “Hope Without the Force: How Andor Rewrites Rebellion,” Nerdist, April 28, 2025, https://nerdist.com/article/star-wars-andor-powerful-revolution-rebellion-without-jedi/.

- Series creator Tony Gilroy has spoken at length about both the upshot and the difficulties of trying to marry the storytelling of Andor to the existing Star Wars canon — which goes beyond the films to include the animated television shows, as well. One of those discussions can be read here: Tony Gilroy, quoted in Kathryn VanArendonk, “‘Before Anyone Else Defines It, I’m Going to Define It’: Andor Creator Tony Gilroy Reflects on Five Years Inside the Star Wars Universe,” Vulture, May 16, 2025, https://www.vulture.com/article/tony-gilroy-andor-star-wars-rogue-one-interview.html.

- “That’s been our attitude all the way through: not to be cynical, and to take it more seriously than anybody ever took it.” This is how Gilroy characterizes his team’s approach to the Star Wars material, which also highlights how vastly different his approach is from Lucas’s. Tony Gilroy, quoted in James Whitbrook, “Tony Gilroy Looks Back on Taking S— Seriously in Andor,” Gizmodo, March 10, 2025, https://gizmodo.com/star-wars-tony-gilroy-andor-interview-season-2-2000573377 [title modified to avoid explicit language].

- Gilroy comments on the inclusion of this character and the theme of destiny, likening her to a “flim-flam psychic” character played by Whoopi Goldberg in Ghost (1990), in Chris Taylor, “‘Andor’ Showrunner Tony Gilroy Explains How the Force Just Awakened,” Mashable, May 7, 2025, https://mashable.com/article/andor-force-tony-gilroy-interview.

- See this classic interview between George Lucas and Bill Moyers to understand the long tradition of mythic storytelling that Lucas intentionally channeled when creating Star Wars: Bill Moyers, “The Mythology of ‘Star Wars’ with George Lucas,” Bill Moyers, June 18, 1999, https://billmoyers.com/content/mythology-of-star-wars-george-lucas/.