This article first appeared in CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL, volume 34, number 06 (2011). The full text of this article in PDF format can be obtained by clicking here. For further information or to subscribe to the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL go to: http://www.equip.org/christian-research-journal/

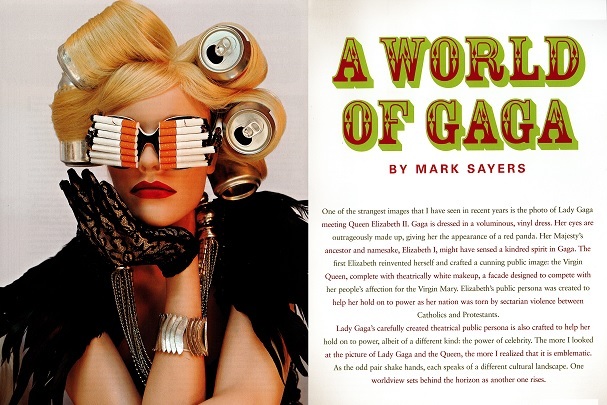

One of the strangest images that I have seen in recent years is the photo of Lady Gaga meeting Queen Elizabeth II. Gaga is dressed in a voluminous, vinyl dress. Her eyes are outrageously made up, giving her the appearance of a red panda. Her Majesty’s ancestor and namesake, Elizabeth I, might have sensed a kindred spirit in Gaga. The first Elizabeth reinvented herself and crafted a cunning public image: the Virgin Queen, complete with theatrically white makeup, a facade designed to compete with her people’s affection for the Virgin Mary. Elizabeth’s public persona was created to help her hold on to power as her nation was torn by sectarian violence between Catholics and Protestants.

Lady Gaga’s carefully created theatrical public persona is also crafted to help her hold on to power, albeit of a different kind: the power of celebrity. The more I looked at the picture of Lady Gaga and the Queen, the more I realized that it is emblematic. As the odd pair shake hands, each speaks of a different cultural landscape. One worldview sets behind the horizon as another one rises.

Surely I am overstating the case. How could a purveyor of puerile pop songs carry such cultural weight? Initially I agreed with this assessment. I would walk through the mall as her music was played, and screw up my face at the sticky sheen sprayed over her manufactured pop. She appeared as just another bad photocopy of Madonna spewing out vacuous Euro dance pop. Yet the juggernaut continued. Just when I thought she would disappear into the celebrity Sheol where one-hit wonders go to be forgotten, she only seemed to gain power.

To understand Gaga, we could explore her life before fame when she was simply known as Stefani Germanotta, raised in an Italian-American family on the Lower East Side. We could try to dig around in the life of the private-school girl, the NYU dropout, the pop culture vulture. We won’t find sufficient Freudian clues here that explain her drive to fame, though, because we would be looking in the wrong place.

To begin to appreciate the cultural phenomenon that is Gaga, we must understand the digital revolution that has sent shockwaves through the music industry and rewritten the rules of youth culture. The entire apparatus of the music industry was built around the building blocks of tangible albums and singles. Whether sold as vinyl or as CDs, they were able to be held in your hand. Then the Internet changed everything: music became digital and was easily passed from one person to another in seconds, and often for no money. Very quickly music lost its profitability. No longer did albums and singles make money.

After the initial shock, the music business began to understand that the money was in concerts, merchandising, and commercial tie-ins. Kids were no longer sitting around bored, listening to records; they were online and overstimulated, sharing and inhabiting the social networking platforms. Everyone understood that a revolution had occurred, yet no one could figure out how to make money out of the new environment. Enter stage left Gaga.

In a time when most are struggling to keep up with emergent technologies and the barely born phenomenon of social networking, Gaga has achieved mastery of this new media landscape. Lady Gaga is the most followed person on Twitter. As I write this, she has almost eleven and a half million followers on Twitter. The blogging platform Tumblr crashed when she launched her own blog there; when her album was released on Amazon, she crashed that site. U.S. sales of her Born This Way album the first week of release were above the million mark, and most of those purchases were digital. In a time when the music industry is struggling to make money, Gaga is printing the stuff for fun. At this moment Lady Gaga is one of the most powerful women in the world, and the most powerful in music. In only a handful of years, she has generated the kind of loyal fan base that other artists take decades to form.

What was different about Gaga? Every band and artist was online and utilizing Twitter and Facebook. Their music could be purchased on Amazon or iTunes. What Gaga—and the marketing teams behind her—managed to achieve was to create a kind of movement. Media commentators Clay Shirky and Seth Godin have both awakened us to the way in which social networking has enabled a new kind of social gathering, one in which followers can connect, share information, and create quick social traction, which in turn can lead to social momentum. We have seen such dynamics occur in places like Iran, and during “The Arab Spring.” These movements were not just simply fueled by social media; rather, it was the confluence of emergent technologies with a narrative that spoke of freedom from repression and totalitarian rule. The same principle applies with the popularity of Gaga, who also attaches a narrative to her music, publicity, and performance.

Gaga’s narrative also speaks of freedom from repression, but for Gaga repression is the constraints that society puts on individuals, and freedom is being yourself, becoming a star, and expressing yourself. Gaga recasts the struggle for freedom from the social and political realms to the individualist and the therapeutic. Gaga’s world is one where freedom is not the opportunity to vote, live, and work in peace, free from oppression. Rather freedom is the opportunity to sleep with whom you want, to take drugs, or to be interviewed by Anderson Cooper in your underwear with a prop saw in your hand. For Gaga, this transgressive approach to art and life is a way of conquering past hurts; rummaging through the history of popular culture is therapeutically salvific. Gaga comments, “I find freedom in my ability to transform and liberate myself (and others) with art and style—because those are the things that freed me from my sadness, from the social scars.”

What is the fount of Gaga’s sadness? What created her social scars? Gaga points to a painful breakup with a past boyfriend, the death of her grandfather, and the bullying she experienced in high school. While we don’t want to denigrate any of these experiences, they are hardly earth-shattering tragedies. Such social scars are made even more ironic once one considers that Gaga stands as the current queen of American popular music, an art form whose roots are born out of the pain of the African American experience. Gaga is no Billie Holiday. She is, instead, a young woman from an upper-middle-class Manhattan family, who attended the same private school as Nikki and Paris Hilton. Gaga’s high school classmates have disputed her claims of isolation and bullying, noting she was popular and successful. Billie Holiday’s rendition of “Strange Fruit” fused African American social exclusion with her own personal pain to create a sublime moment where American popular music became both high art and social protest. Gaga, in a far more calculated move, also attempts to do the same: to move into the world of high art and to articulate her audience’s pain. Gaga’s sadnesses, however, are typical upper-middle-class woes, but that is the point—they are accessible to those who buy her music and her message.

Gaga’s therapeutic message seems at odds with the visuals of her art. On one hand you have the Gaga persona of a polite young woman on Good Morning America encouraging young people who are being bullied to believe in themselves and pursue their dreams. On the other hand, we have the Gaga persona appearing on stage and in music videos blending images of sex, death, and violence. Cultural critic Camille Paglia speculates that Gaga represents the death of sex, noting, “Despite showing acres of pallid flesh in the fetish-bondage garb of urban prostitution, Gaga isn’t sexy at all—she’s like a gangly marionette or plasticised android. How could a figure so calculated and artificial, so clinical and strangely antiseptic, so stripped of genuine eroticism have become the icon of her generation? Can it be that Gaga represents the exhausted end of the sexual revolution?”

I am not sure that Gaga represents the death of sex. Rather I think that her art resonates with a generation whose worldview is shaped by a torrent of media in which sex and violence are inextricably linked. Gaga’s music and art is designed for a generation for whom sexual abuse is the norm and hardcore pornography is part of the wallpaper of everyday life. These teens and young adults inhabit a world in which sex is no longer just about overexcited teenage hormones, but rather is an avenue toward social power. Gaga resonates with those navigating gender confusion, sexual dysfunction, the reality of absent parents, and who face the specter of self-harm. The illogical disconnect between Gaga’s feel-good therapeutic message on daytime TV and the Dionysian themes of her performance art makes perfect sense to a conflicted generation who some days want to reach for the stars and other days just want to lie in the gutter, wasted.

Mark Sayers is the senior leader of Red Church in Melbourne, Australia, as well as being the creative director of Uber Ministries. He is the author of The Trouble with Paris: Following Jesus in a World of Plastic Promises (Thomas Nelson, 2008), The Vertical Self: How Biblical Faith Can Help Us Discover Who We Are in an Age of Self Obsession (Thomas Nelson, 2010), and, most recently, The Road Trip That Changed the World: The Unlikely Theory That Will Change How You View Culture, The Church, and Most Importantly Yourself (Moody, 2011).

NOTES

- http://www.vmagazine.com/2011/05/from-the-desk-of-lady-gaga/?page=2.

- http://www.thesundaytimes.co.uk/sto/public/magazine/article389697.ece.