This article first appeared in the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL, volume 37, number 06 (2014). The full text of this article in PDF format can be obtained by clicking here. For further information or to subscribe to the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL go to: http://www.equip.org/christian-research-journal/

SYNOPSIS

“Originally a niche medium, anime (Japanese animation) has experienced a massive explosion in popularity in recent decades. Its cultural influence is widespread, from massive conventions full of truly devoted fans to Hollywood’s biggest blockbusters and family films. However, anime can be daunting to explore and understand due to both cultural differences as well as its willingness to feature more mature themes and subject matter than are usually found in American animation (including sex and violence). While this is cause for concern, anime’s willingness to wrestle with serious themes also means that it contains numerous titles that parallel Christian theology in surprising ways, and are worth the discerning believer’s consideration. Studio Ghibli has become the most celebrated studio in anime history thanks to its beautifully rendered tales full of moral complexity and ambiguity. Ghost in the Shell offers a cyberpunk look at technology’s challenges to our definition of what it means to be human. One man’s never-ending search for atonement and forgiveness is at the heart of Rurouni Kenshin’s samurai tale. Haibane Renmei’s depiction of the wages of sin and self-righteousness could easily have been lifted from 1 John’s opening chapter. And finally, Attack on Titan is a violent and harrowing look at what it means to live in an apparently materialistic and godless universe. Titles like these not only offer Christians some fascinating explorations of important themes but also provide a way for believers to engage with one of pop culture’s most dynamic influences.”

When Katsuhiro Ôtomo’s Akira was released in the United States in 1988, it was a ground-breaking event. Anime (Japanese animation) had been released in America before Akira (e.g., Speed Racer, Star Blazers, Robotech), but in heavily edited forms aimed at younger audiences. This wasn’t the case with Akira, which had more in common with Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner. It was violent and dystopic in tone and revealed that Japanese animators weren’t afraid to deal with serious themes (e.g., human and political corruption, science run amok, social upheaval) that were decidedly not for children.

Since Akira’s release, anime has experienced booming popularity. Series including Bleach, Naruto, and Fullmetal Alchemist—to name but a few—reach massive audiences via Cartoon Network’s Adult Swim and streaming services such as Netflix, Hulu, and Crunchyroll. Fans attend massive conferences and the truly devoted (often called “otaku”) engage in “cosplay” wherein they dress up as and impersonate their favorite characters, often elaborately so.

Anime has also moved far beyond otaku circles. Its influence can be found in Disney and Pixar movies; big budget Hollywood blockbusters like the Matrix trilogy, Avatar, and Pacific Rim; and popular American animation series including Avatar: The Last Airbender and The Clone Wars. Even The Simpsons, that bastion of American animation, featured an anime-inspired segment in a 2014 episode titled “Married to the Blob.”

But this growing cultural impact has a darker side: anime often contains disturbing, graphically violent, and sexually explicit content. Even so, Christians should think twice before condemning, or worse, simply dismissing anime. Because of its willingness to address serious, mature topics not usually associated with cartoons (as Akira did in 1988), anime is also full of rich stories bursting with imagination and thematic richness that can provide a thought-provoking experience for discerning Christians.

Anime can be daunting to explore. There are, of course, many cultural differences inherent in anime. Being a Japanese cultural product, anime is created for Japanese audiences, first and foremost. As such, it comes with cultural “baggage” (e.g., social and cultural mores, worldviews, and spiritual concepts) that doesn’t always translate easily to a Western context and thus takes time for non-Japanese viewers to unpack. (A book like Patrick Drazen’s Anime Explosion! [Stone Bridge Press, 2002] can be very helpful in this task.)

Unpacking anime’s cultural baggage can be difficult, but it can be an enjoyable and educational experience. Unfortunately, there’s another reason why anime can be daunting to explore, especially for Christians. Even the most cursory of Google searches will reveal numerous anime titles of a fairly prurient and/or violent nature. (This is true even after considering cultural differences concerning sexuality, nudity, language, and violence.) Spend time researching anime, and you’ll inevitably discover terms like “ecchi” and “hentai” (i.e., types of sexually graphic anime). Spend time watching anime, even seemingly innocuous titles, and you’ll inevitably encounter “fan service” (i.e., gratuitous content and scenes that exist mainly to titillate).

Any discussion of anime, at least from a Christian perspective, must acknowledge this problematic aspect. Sifting through titles to find worthwhile content can be challenging for even the most discerning and experienced viewers. This is doubly true when choosing anime for children; as pointed out earlier, the Japanese don’t consider animation to be primarily a children’s medium.

But I want to suggest that the challenge of exploring anime is well worth it. There are several anime titles and franchises, some of which I’ve highlighted below, that are not only aesthetically and artistically praiseworthy but also imaginative and thought provoking. These stories can dovetail with Christian theology in some surprising ways. Watching them can provide much food for thought for Christians, and even lay the foundation for important conversations.

STUDIO GHIBLI: UNNERVING AND PROFOUND MORAL AMBIGUITY

I begin with arguably the most revered name in anime today: Studio Ghibli, which was founded in 1985 by directors Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata. For nearly three decades, Studio Ghibli has created some of the most beloved, acclaimed, and beautiful titles in anime’s history.

Studio Ghibli’s filmography is quite diverse. It includes whimsical fantasies (My Neighbor Totoro, Kiki’s Delivery Service), harrowing war titles (Grave of the Fireflies, Princess Mononoke), and charming melodramas (Only Yesterday, From Up on Poppy Hill). Regardless of genre, though, certain themes and qualities undergird the studio’s output.

First, their films are typified by an idyllic and gently nostalgic atmosphere that prefers the rural and natural to the urban and technological. Examples include Only Yesterday’s pastoral scenery and celebration of rural living as well as From Up on Poppy Hill’s plot about students fighting to save their old clubhouse from the rapid modernization of post- World War II Japan.

Second, their films often feature a pacifist outlook that doesn’t shy away from depicting war, but also never glorifies it. Conflict and violence may be unavoidable and even necessary in a film like Princess Mononoke, but they are always lamented.

Third, while anime (like much American entertainment) often seems like little more than young male wish fulfillment, films like Kiki’s Delivery Service, Whisper of the Heart, and The Secret World of Arrietty feature strong, complicated female protagonists, which can be a breath of a fresh air. (This is especially true for those seeking good pop culture role models for their daughters.)

The quality, though, that may be of most interest to Christian viewers—and the quality bound to spark the most interesting conversations—is their films’ often ambiguous morality. This may seem an odd and problematic statement at first, but Studio Ghibli’s reluctance to draw clear lines between “heroes” and “villains” makes for films that ring deeply true concerning the complexity of the fallen human nature.

Sometimes, as with Spirited Away—which won the 2003 “Best Animated Feature” Oscar—the ambiguity is gentle, even comical. Spirited Away’s heroine is a young girl named Chihiro who becomes lost in the spirit world after her family discovers a seemingly abandoned amusement park. To survive, she gets a job at what’s essentially a spa for spirits. Nobody there is quite what they seem, not even Chihiro, who starts off the film as a petulant ten-year-old but grows in maturity, thanks to discipline and friendship. And that which is most monstrous and fearsome in the menagerie of Chihiro’s coworkers and customers may turn out to be a friend in need, a wise patron, or a misguided soul in need of some grace and kindness.

But sometimes the ambiguity is more disturbing—and more profound. Princess Mononoke, one of Studio Ghibli’s darkest films, follows the journeys of a young prince named Ashitaka who is cursed after saving his village from a monster. The monster turns out to be a nature spirit that was driven insane after being wounded by a bullet. Leaving his village to find a cure, Ashitaka eventually finds the bullet’s source: a bustling town named Iron Town run by the ruthless and ambitious Lady Eboshi.

Initially, Princess Mononoke seems like a simplistic “nature good, humanity bad” environmental tale. But then we learn Iron Town’s secret: it is populated by lepers, prostitutes, and other outcasts who’ve been drawn to Lady Eboshi because she alone offers them a productive, dignified life. (In one poignant scene, a leper tells Ashitaka that Lady Eboshi was the only person willing to care for him and clean his wounds.) Meanwhile, the nature spirits (e.g., boars, wolves, apes) are far from the innocent forest creatures we expect. Rather, they are just as selfish, vain, and violent as humans. Suddenly, what seemed like an obvious black-and-white tale is colored in shades of gray and becomes more complicated, morally, and more interesting and affecting.

GHOST IN THE SHELL: WHERE DOES THE FLESH END AND THE SOUL BEGIN?

Several years ago, I attended a Christian conference where the topic was how advances in artificial intelligence, genetic engineering, and neuroscience were challenging traditional notions of what it means to be “human.” Looking back, I can’t help but think that Mamoru Oshii’s Ghost in the Shell should have been screened during the conference. Few titles, anime or otherwise, have explored this topic with as much thought or style.

Based on Masamune Shirow’s cyberpunk manga, the Ghost in the Shell franchise includes several movies and television series set in a futuristic Tokyo. They all chronicle the exploits of Public Security Section 9, a covert government agency that confronts espionage, terrorism, and cybercrime. Section 9’s top agent is Motoko Kusanagi, a cyborg whose entire body is artificial. This gives her enhanced speed and strength as well as the ability to interface directly with the world’s ubiquitous computer networks—but at what cost?

One of Ghost in the Shell’s primary concepts is that humans possess a “ghost,” or consciousness, that differentiates them from artificial intelligences. Though materialistic in origins (i.e., your ghost is not the same as your soul), there is nevertheless great concern over what happens to your ghost as you artificially enhance your body. Kusanagi often reflects on her ghost’s state, and while she indulges in sensual pleasures and bucks social norms with her dress and conduct, she nevertheless remains aloof—more machine, it seems, than human.

As Christians, we do not subscribe to the Gnostic concept that we are souls wrapped in evil flesh. Rather, we are both souls and bodies intricately woven together (which is why we believe that both our souls and bodies will be renewed at the end of all things). Ghost in the Shell poses an interesting question about the nature of that relationship, one that may become more pressing as cybernetics and genetic engineering become more common. Specifically, as we alter our bodies and transcend the limits of what is traditionally considered “human,” to what extent are we affecting our nonphysical facets—our souls, consciences, and so on? Not in the sense of affecting our salvation, but rather concerning our capacity for empathy and concept of shared humanity.

There’s another theme at work in Ghost in the Shell, too. Its world is populated by machines and software all possessing varying levels of intelligence. In the first Ghost in the Shell movie, a government computer program gains sentience and seeks political asylum. Meanwhile, in the Stand Alone Complex TV series, some of Section 9’s robots become self-aware and find themselves pondering ethical and philosophical issues.

Here, the franchise raises questions about our relationship to the things we create. God created us in His image, and similarly, we create things in our own image that “think” and act like us to varying degrees. What happens when such technology becomes so advanced that it becomes “aware” for all intents and purposes, and its behavior becomes virtually indistinguishable from that of humans? (Given modern developments in computing power and software development, this may not be as far-fetched as it seems.) What are our obligations to our creations, and does the emergence of “aware” technology threaten our humanity?

Ghost in the Shell’s prevailing stance seems to be uneasy coexistence. Technology is so ubiquitous that people cannot resist its incorporation into their lives. We may not have police cyborgs and self-aware computer programs right now, but Ghost in the Shell confronts us with scenarios for the future that are at least worth pondering.

RUROUNI KENSHIN: A SAMURAI ASSASSIN’S REDEMPTION

The samurai is an enduring symbol of Japanese culture, and possibly the most famous one, thanks to classic samurai films such as Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai, Yojimbo, and Ran. Not surprisingly, many anime titles have featured samurai exploits. Few, though, have featured a samurai quite like Rurouni Kenshin’s.

Based on Nobuhiro Watsuki’s long-running manga series, itself heavily inspired by Japanese history, Rurouni Kenshin tells the story of a former assassin named Himura Kenshin. In the past, Kenshin killed countless people to overthrow a corrupt government. He now wanders Japan, seeking to atone for his bloody deeds, and has vowed never to kill again. He takes this vow so seriously that he now wields a reverse-blade sword that endangers his life in any confrontation, since its sharpened edge is always pointing at him.

Kenshin’s atonement, though, is made difficult as former enemies and others seek after him, hoping to avenge their comrades and/or test their skills against the legendary assassin. These opponents are not above endangering Kenshin’s newfound friends, which include a budding love interest and a young pupil, to get to him.

It’s easy to dismiss Rurouni Kenshin since it starts off in a rather silly, uneven fashion. But look past the goofy animation, over-the-top melodrama, and broad comedy, and you’ll find a surprisingly thoughtful tale of atonement, redemption, and the search for grace. This shouldn’t surprise Christians; even the most hardened thirst for grace, but few have the dedication to change their lifestyle dramatically—such as a former samurai assassin who literally turns his own sword on himself—to atone for their sins.

Bookending the events of Rurouni Kenshin are the Samurai X movies. Done in a darker, more realistic and violent style, these movies reveal Kenshin’s history, including his assassin training, his first love, and the tragic origins of his famous cross-shaped scar—as well as the eventual end of his search for redemption. They also explore the effects that his actions, both peaceful and violent, have had on friends, lovers, enemies, and even the nation of Japan as a whole.

Kenshin’s story ends on a deeply bittersweet note. In doing so, it encourages us to reflect on the myriad effects that our own actions, righteous or sinful, can have without us ever knowing. Like a former samurai assassin, this should drive us to seek atonement and yearn for forgiveness and grace, all of which, we are blessed to know, are found freely in Christ alone.

HAIBANE RENMEI: BREAKING THE CIRCLE OF SIN

Chances are that while watching Haibane Renmei, you’ll often feel like you have no idea what’s going on. It’s a strangely disquieting feeling, and yet it’s one of the series’ great strengths. You are constantly made to reassess the series’ storyline and characters with nearly every episode as it moves inexorably toward a stunning, deeply moving conclusion.

Haibane Renmei is set in a pastoral, vaguely European village named Glie surrounded by a giant wall. Citizens can’t pass beyond the wall; even touching it is forbidden. Only the Toga, a group of robed and masked individuals who communicate via sign language, travel to the unknown lands beyond the wall.

Born into this world—via cocoon, no less—are haibane: angel-like beings complete with wings and halos. Unlike angels, haibane don’t seem to be supernatural creatures. Instead, they seem to exist only to serve Glie’s citizenry. Each haibane is required to find a patron or job and contribute to society while living an ascetic lifestyle.

Rakka is the newest haibane, and the series’ early episodes focus on her efforts to befriend her fellow haibane and find her place in Glie’s tranquil society. Rakka is inquisitive for a haibane, though, and she grows increasingly curious concerning both her existence and the nature of Glie and the wall—questions that come to a head when another haibane disappears one night beyond the wall.

Haibane Renmei is a gently contemplative series reminiscent of Studio Ghibli’s works, and it’s easy to become lulled by its lovely artwork and slow pace. But as Rakka comes closer to learning the true nature of the haibane as well as the wall’s purpose, the second half takes a darker turn.

One of the series’ central concepts is the “circle of sin,” which binds haibane and prevents them from moving beyond the wall to another existence. In a crucial scene, Rakka engages in semi-theological debate with the Communicator, the mysterious figure who oversees the haibane. Their dialogue could have been lifted from 1 John’s first chapter.1

Communicator: To recognize one’s own sin is to have no sin. So, are you a sinner?

Rakka: But if I think I have no sin, then I become a sinner!

Communicator: Perhaps this is what it means to be bound by sin. To spin in the same circle, looking for where the sin lies, and at some point losing sight of the way out.

Haibane that are unable to break the “circle of sin” become “sin-bound” and can’t move beyond the wall. Instead, their wings blacken and they become isolated. In its second half, Haibane Renmei focuses on one particular “sin-bound” haibane. Rather than accept grace and kindness from those around her, she works hard to hide her sin-bound nature while proving her worth and value under the guise of caring for Rakka and others. Ultimately, though, her works drive her to isolation and despair, and in the final episodes, much of the series’ drama comes from whether she’ll ask for mercy or remain on her doomed path.

As far as I know, Haibane Renmei creator Yoshitoshi Abe is not a Christian. (For example, his choice of the haibane’s angelic look was driven by aesthetics, not religious beliefs.2) Nevertheless, Haibane Renmei does a remarkable job of displaying the effects of sin and self-righteousness in ways that resonate with Christian theology and provide much food for thought and reflection.

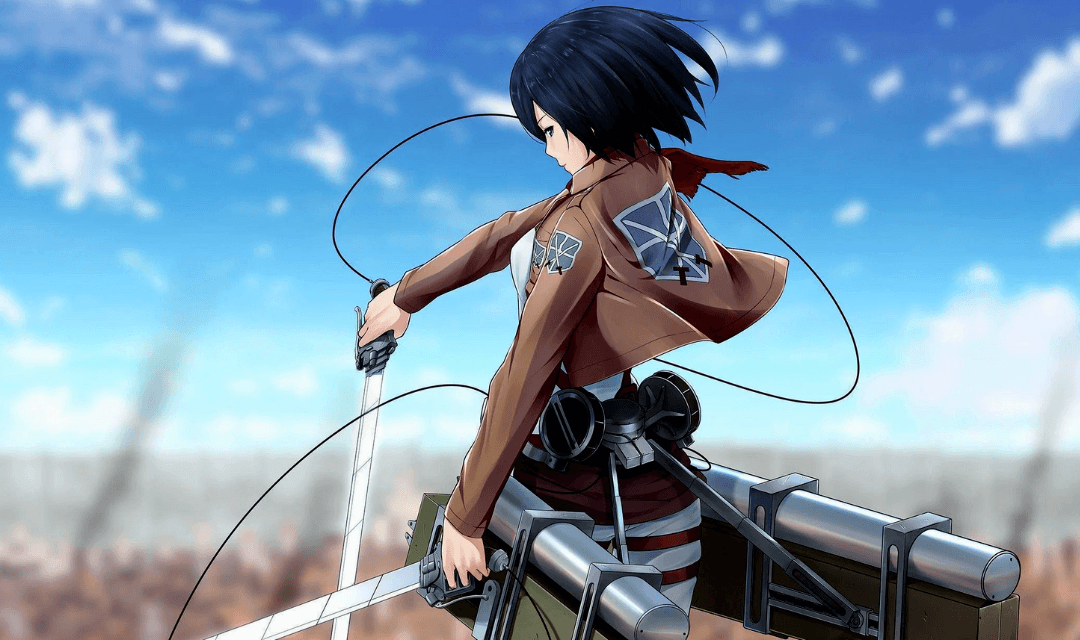

ATTACK ON TITAN: HOW DO WE LIVE ON IN A WORLD OF HORROR?

Arguably 2013’s biggest anime hit, Attack on Titan is bracing, constantly intriguing, and packed with exhilarating action. It’s also very difficult to watch, not just because of its violence and gore, but also because of the desperation filling its episodes.

A century before the series’ events, humanity was nearly annihilated by the “titans,” massive humanoids whose only purpose seemed to be devouring humans. Humanity’s surviving remnants now live a quasi-feudal existence behind a series of massive walls. After a century, though, humans have grown complacent. This complacency is shattered, however, when the titans suddenly reappear, breach the outermost wall, and begin consuming the populace.

One of the survivors is Eren Yeager, a headstrong lad who has always dreamed of journeying beyond the walls. After a titan devours his mother before his eyes, his thoughts turn to revenge, and he joins the military in hopes of destroying them. This is easier said than done: titans are nigh-invulnerable and the sight of one can produce sheer terror and hopelessness in even the most hardened soldiers.

Attack on Titan is thrilling to watch. The scenes of Eren and his comrades battling the titans are some of the best action sequences I’ve seen in a long time, animated or otherwise. However, it’s also incredibly brutal. Nobody is safe from the titans; anyone can become a titan snack in the blink of an eye.

Aside from a cult that worships the walls, religion is largely absent in Attack on Titan. As such, there is virtually no hope in the series. Indeed, the series’ prevailing atmosphere might best be described as Bertrand Russell’s “slow, sure doom.” People either go mad at the sight of the titans or buck themselves up with grim resolve to go down swinging. The noblest exercise in Attack on Titan is, indeed, “a long march through the night…tortured by weariness and pain.”3

With its portrayal of a nigh-hopeless situation for humanity, Attack on Titan could be a fascinating exercise in anti-apologetics. That is, what does it look like to live in a world where mankind really is nothing but something to be literally chewed up and spit out? Qualities such as friendship, loyalty, and honor still exist amongst Eren and his comrades, but how? And more importantly, why? To be fair, Attack on Titan isn’t finished yet. A second season is being produced and the original manga isn’t finished either, so it remains to be seen how these themes will play out. In the meantime, Attack on Titan remains one of the more unique and action-packed anime titles in recent years, provided you have a strong stomach.

The titles I’ve discussed here represent the tip of the iceberg: we could also consider the works of Satoshi Kon, Mamoru Hosoda, Shinichir Watanabe, and Makoto Shinkai, to name a few more acclaimed anime filmmakers. But it should hopefully be apparent now that anime is more than mere children’s fare, and much more than the disturbing content that so often gets the spotlight. Since anime’s cultural influence shows no signs of abating (consider Disney’s recent Big Hero 6), Christians would do well to pay closer attention to the medium. With a critical and discerning eye, they might just be surprised by the beauty and insights discovered therein.

Jason Morehead is a blogger and web designer living in Lincoln, Nebraska. He has written extensively about anime and Japanese pop culture for various websites including opus.fm, christandpopculture.com, theotherjournal.com/ filmwell, and twitchfilm.com.

NOTES

- Haibane Renmei, episode 9, directed by Tomokazu Tokoro and written by Yoshitoshi Abe, first broadcast on December 4, 2002 (Fuji Television and Animax).

- “Sekai no Hajimari: A Haibane Renmei fan page,” http://cff.ssw.net/main/faq.htm#4.1.2, accessed September 3, 2014.

- Bertrand Russell, A Free Man’s Worship (essay, 1903).