When you to subscribe to the Journal, you join the team of print subscribers whose paid subscriptions help provide the resources at equip.org that minister to people worldwide. These resources include our ever growing database of over 1,500 articles, as well as our free Postmodern Realities podcast.

Another way you can support our online articles is by leaving us a tip. A tip is just a small amount, like $3, $5, or $10 which is the cost for some of a latte, lunch out, or coffee drink. To leave a tip, click here

Christian theology regards human beings as creatures standing both within and beyond nature, the material world. Although exceptions as old as Lucretius abound, this belief is also found outside the Christian faith. So far as we can tell, humans are the only creatures who distinguish themselves in this way. Mary Oliver, best known for her Pulitzer-prize-winning poetry collection American Primitive (Atlantic/Little, 1983), believes animals rejoice at being alive in this world but knows they do not question their place in it. Given this difference between us and the rest of the cosmos, it is reasonable to wonder if nature can tell us anything significant about our spiritual selves or lead us to God.

Oliver’s poems — anchored by close, attentive descriptions of the natural world — reach beyond the physical to consider the nature of God and human beings, and the possibilities of life after death. Her works detail the beauty, fragility, cruelty, and kindness of the natural world. From it, she gleans hints about human life, attentiveness yielding wonders — both glorious and terrible — that would otherwise pass her by. Forming her to receive the world as a gift, attentiveness draws Oliver ever more deeply into the world’s always deepening depths. She is surprised by revelations, moved by beauty, solaced by a creature’s contentment with itself, instructed by its willing consent to be what it is given to be. Imagining a conversation with a fox, she reports him saying, “You fuss over life with your clever words, mulling and chewing on its meaning, while we [animals] just live it.”1 If nature can justify definite spiritual conclusions, Oliver’s work should offer guidance.2

Concentrated Attention

Central to her work is a paradox: her growing amazement at a world that she observes again and again. In Thirst, Oliver describes this paradox as “standing still and learning to be astonished” (emphasis added).3 Because she learns by standing still, Oliver demonstrates that astonishment is both natural and cultivated. Her sensibility, honed by repeated attention to the same old things, is a birth-right gift of temperament wedded to disciplined work. “Everyone,” she insists, “should be born into this world happy / and loving everything. / But in truth it rarely works that way. / For myself, I have spent my life clamoring toward it.”4 Her method of clamoring — concentrated attention — though it lingers upon the material world, penetrates to vistas of the spirit.

For example, Oliver meditates at length on roses whose practical consent to life and death — from first bud, to mature flower, to decline and death — reveals a virtue she would repeat herself. “[T]he last roses,” she notes, “have opened their factories of sweetness / and are giving it back to the world. / . . . I wouldn’t mind being a rose / in a field full of roses. / Fear has not yet occurred to them, nor ambition. / . . . Neither do they ask how long they must be roses, and then what.”5 To Oliver, roses are remarkable precisely because they consent to be exactly what they are. The possibilities of beauty lie in that consent. For the beauty of roses to enter this world, roses themselves must consent to the stream of material life. Toward a similar consent she clamors, remarking, “I wake with thirst / for the goodness I do not have.”6 Insisting that “all beautiful things, inherently, have this function — / to excite the viewers toward sublime thought,”7 Oliver ponders roses until their sublime fearlessness shines through.

Nature grasps Oliver so because her temperament coincided with her circumstances to form her soul. By temperament sensitive to nature’s beauty, Oliver developed deep affection for it during childhood, in part because the woods were a sanctuary from her abusive home.8 A quiet, reflective child, she grew to be an astute observer of nature, becoming more meditative by meditating upon it. She was also always reading. Speaking of her favorite authors, Oliver says, “With them I live my life, with them I enter the event, I mold the meditation….And I do not accomplish this alert and loving confrontation by myself and alone, but…with this innumerable, fortifying, company, bright as the stars in the heaven of my mind.”9 For Oliver, nature’s lessons are what they are because observation and reading combined to shape her inner life. Apparently, what the natural world can say about humanity or God depends as much upon the person listening as upon the world itself.

Transcendence

Thus, resisting avarice, Oliver receives the world as a gift. In House of Light, she recalls a moment when she cupped a tiny pipefish in the palms of her hands, admiring the light reflecting from its body. Noting its squirming efforts to reclaim its watery freedom, she writes, “I opened my hands — / like a promise / I would keep my whole life / and have — / and let it go.”10 Relinquishing control, she finds the world gives itself to her in profound experiences that would otherwise be impossible — an early-morning encounter with two deer so disarmed by her stillness that one of them touches her with its nose.11

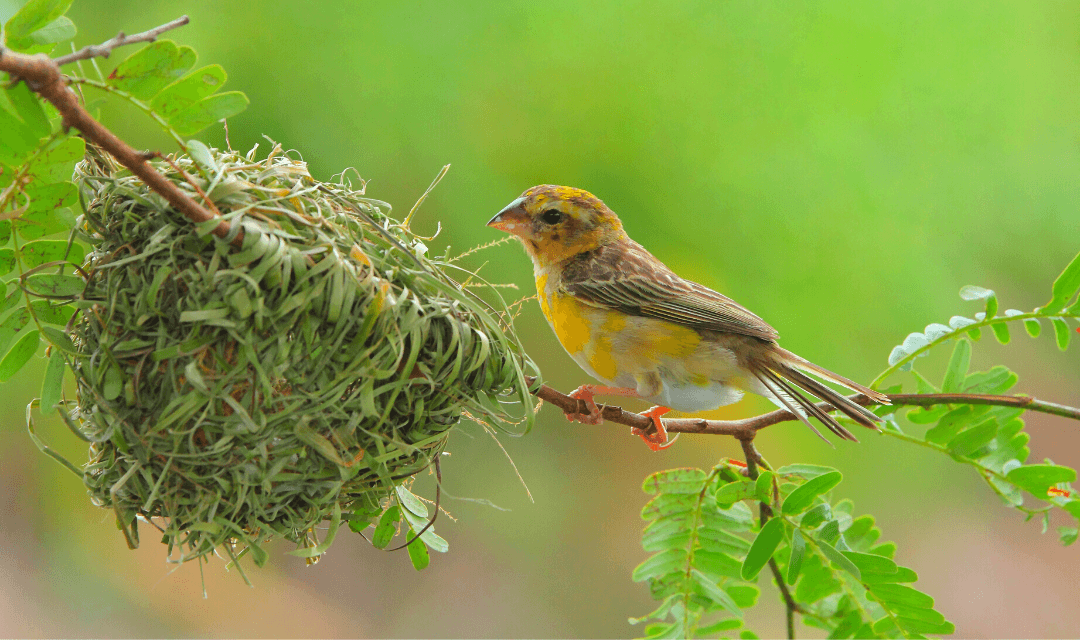

Even the skeletons of dead fish offer hints of transcendence, an intricate beauty that suggests design. “I don’t,” she insists, “think / it was just a floundering / in the darkness, / no matter how much time there was.”12 Chance, perhaps, is at work; but not mere chance. The sheer spectacle of what exists suggests a robustly fecund mind: a great artist, intoxicated by the possibilities of life, with joyful abandon spews beings forth.13 Often she is stunned by creatures who persist in the face of difficulty, birds surviving brutal winters,14 turtles exhausting themselves to lay and secure their eggs,15 “the determination of the grass to grow despite the unending obstacles.”16 This great push to keep the stream of life flowing exceeds the particular life of the individual creature.17 Thus do these creatures give evidence that something transcends nature, drawing it along in a stream-of-being.

Inexorable Death

Despite her reverent, open-hearted wonder, Oliver sees how utterly life depends upon death. Owls kill rabbits, cranes eat fish, and dogs sometimes savage seagulls. A part of this pattern herself, she lives from the fish and other creatures that occupy the ponds and the ocean around Provincetown, Massachusetts. That life for one creature demands death for another opens a mystery about the divine nature. Recalling Teilhard de Chardin, Oliver says, “man’s most agonizing spiritual dilemma is his necessity for food, with its unavoidable attachments to suffering.”18 Relying solely upon observation alone, one might easily conclude that death, even violet death, never troubles the divine mind. Nevertheless, to any thoughtful human, this state of the world is troubling. Besides, however stoically we come to accept the deaths of animals, we find it far more difficult to accept the passing of the people we love.

Even the non-human things we love — trees for instance — have a value that makes their loss unsavory. In one poem, Oliver reflects on the death of an oak tree that had, over the years, become especially precious to her. As she recalls the usual comforts, she stumbles upon the problem of particularity. Not oak trees per se, but this oak tree — fallen now, uprooted, its heart rotted and dead — is the thing she loved. Pondering the loss of this specific tree whose form and presence, unrepeatable, are gone for good, she recalls the myth of Osiris who leaves his home and returns but so changed as to be unrecognizable. She notes her dissatisfaction: however good is the Osiris who returns, the Osiris who left is permanently lost. This loss cannot be restored by the return of a different Osiris nor the loss of a tree by another of the same kind. Oliver cherished one specific tree. But it is gone.19 So what are we to do about that?

Which conundrum leads to some insight about nature’s ability to lead us to God. In an interview with Krista Tippet, Oliver admits life-long uncertainty about the Christian doctrine of the resurrection, a doctrine which has no analogue in nature.20 Though the cycle of the seasons returns roses to the rosebush, it returns new ones. Each spring’s crop is altogether new, not the previous spring’s flowers reborn. Closer to the point, the animal that dies, though its dissolution provides the molecular materials for another creature, never itself returns. Exactly to the point, the person who dies disappears altogether. Thus, Oliver asks her reader, “Do you think there is any / personal heaven / for any of us? / Do you think anyone, / the other side of that darkness, / will call to us, meaning us?”21 Her question is genuine. Though she believes in God, because she relies so heavily upon nature as teacher, she really cannot tell if or how an individual person might persist after death.

In the same interview, she expresses admiration for Lucretius and his theory of atomic dissolution and re-organization. She draws comfort from the thought that the atoms which compose her, once dissolved, will re-organize in the bodies of other creatures. This, she says, is a compelling form of life after death. Yet Oliver’s claim of comfort mystifies me because Lucretian philosophy, though it sees life itself as perpetual, sees no particular living thing as such. It posits no continuation of the particular consciousness that Oliver is, without which she cannot be said to live. However long the atoms that compose her persist, if they do not do so in a form that supports her consciousness, then she exists no longer, lost to the world and to God. For Oliver to live after she dies, her soul must return to her own body. Only the Christian doctrine of resurrection offers this hope.

A Definitive Hope

Of course, the question is not whether the Christian doctrine of resurrection or the Lucretian doctrine of atomic reorganization provides greater comfort, but whether Christ or Lucretius offer a true account of human existence and eternal life. Which question brings us to the limits of nature, revealing its insufficiency as a pattern for the human heart. “Attention,” writes Oliver, “is the beginning of devotion,”22 and with such devotion she both begins and ends. Admirably attentive to the divine gift of the material world, to its spiritual whisperings, she is ripely poised to receive such wisdom as nature offers, her gentle, truthful spirit marked by humility, gratitude, and wonder. Without this wisdom, without her poetry as an invitation to this wisdom, our world would be a lesser place. My own spiritual life would lack the light that her keen spirituality provides. But there remains a point beyond which nature cannot take us; for nothing in nature guarantees the persistence of any particular life after death; nothing speaks unambiguously of the love of God. Nature offers glimpses, hints of a divine nature and enough truth and beauty to inspire profound wonder. Such hints may prepare the soul for revelation by encouraging stillness, gratitude, reverence, and love.

If, however, nature were enough, Christ would be superfluous. St. Bonaventure claims, “we are so created that the material universe itself is a ladder by which we may ascend to God.”23 But he also insists, “we cannot rise above ourselves unless a superior power raise us,” a power he identifies as Christ in whom we have definitive hope for life in the face of death.24 Because He is truth both incarnate and transcendent, Christ overrules the norms of nature. He had no precedent. Thus were His disciples, men intimate with the natural world, stunned by His resurrection. Nature offered no anticipation of this event. Thus was Paul deemed mad by many to whom he witnessed. The men and women of the ancient world knew, as well as we do today, that the dead do not rise. To do that requires a power greater than nature can muster. No cycle of water, no wheel of the seasons, no pattern of growth and decay can solve the predicament of human mortality. It is Christ, or it is Lucretius. For they offer different things.

Stephen Mitchell writes and teaches English in North Carolina. He holds a PhD in humanities.

NOTES

- Mary Oliver, “Good-bye Fox,” A Thousand Mornings (New York: Penguin Books, 2012), 14.

- Editors’ note: The late poet Mary Oliver, whose work was “deeply resonant with contemporary lesbian consciousness,” professed no formal relation to the historic Christian faith. Tina Gianoulis, “Oliver, Mary (b. 1935),” GLBTQ, c. 2005, http://www.glbtqarchive.com/literature/oliver_m_L.pdf; Mary Oliver, “I Got Saved by the Beauty of the World,” On Being with Krista Tippett, February 5, 2015, https://onbeing.org/programs/mary-oliver-i-got-saved-by-the-beauty-of-the-world/; Ruth Franklyn, “What Mary Oliver’s Critics Don’t Understand: For America’s Most Beloved Poet, Paying Attention to Nature Is a Springboard to the Sacred,” New Yorker, November 20, 2017, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/11/27/what-mary-olivers-critics-dont-understand.

- Mary Oliver, “Messenger,” Thirst (Boston: Beacon Press, 2006), 1.

- Mary Oliver, “Halleluiah,” Evidence (Boston: Beacon Press, 2009), 19.

- Mary Oliver, “Roses, Late Summer,” House of Light (Boston: Beacon Press, 1990), 66–67.

- Oliver, “Thirst,” Thirst, 69.

- Oliver, “Evidence,” Evidence, 43.

- Oliver, “I Got Saved by the Beauty of the World.”

- Mary Oliver, “Sister Turtle,” Upstream: Selected Essays (New York: Penguin Books, 2016), 57–58.

- Mary Oliver, “Pipefish,” House of Light (Boston: Beacon Press, 1990), 38.

- Oliver, “The Place I Want to Get Back To,” Thirst, 35–36.

- Oliver, “Fish Bones,” House of Light, 50.

- Oliver, “Fish Bones,” House of Light, 50–51.

- Oliver, “Herons in Winter in the Frozen Marsh,” House of Light, 68–69.

- Oliver, “Sister Turtle,” 51–56.

- Oliver, “Evidence,” 44.

- Oliver, “To Begin With, the Sweet Grass,” Evidence, 37.

- Oliver, “Sister Turtle,” 56.

- Oliver, “The Oak Tree at the Entrance to Blackwater Pond,” House of Light, 52–53.

- Oliver, “I Got Saved by the Beauty of the World.”

- Oliver, “Roses, Late Summer,” 66.

- Oliver, “Upstream,” Upstream, 8.

- St. Bonaventure, The Journey of the Mind to God, trans. Philotheus Boehner, O.F.M. (Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing, 1956), 5.

- St. Bonaventure, The Journey of the Mind to God., 5–7.