When you to subscribe to the Journal, you join the team of print subscribers whose paid subscriptions help provide the resources at equip.org that minister to people worldwide. These resources include our ever growing database of over 1,500 articles, as well as our free Postmodern Realities podcast.

Another way you can support our online articles is by leaving us a tip. A tip is just a small amount, like $3, $5, or $10 which is the cost for some of a latte, lunch out, or coffee drink. To leave a tip, click here

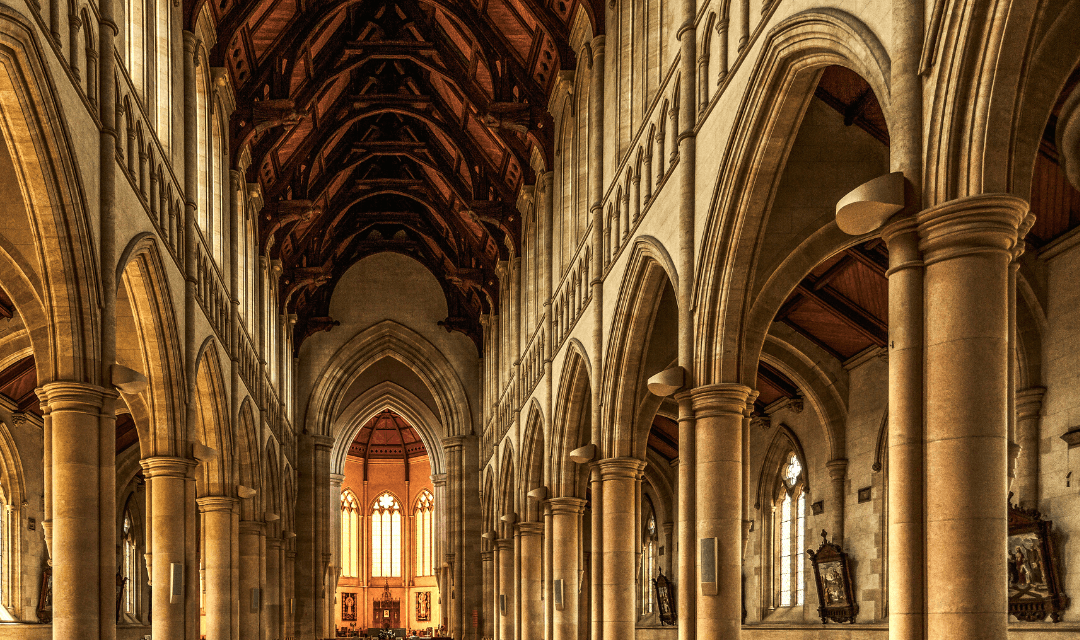

“Would you like one?” I asked, holding out the unprepossessing liturgical calendar my church gives away in January. My prey leaned in close to whisper, “It’s the wrong funeral home.” Confused, I peered at the cover. Besides the plain photo of our nave, all I could see was a block of tiny lettering — church name, year, address, and then, yes, our calendar does have the name of a local funeral home there on the front. The person upon whom I was trying to foist this “gift” runs a similar establishment two towns over. “I’m so sorry,” I whispered back, “you’re right.”

Whichever funeral home, it is fitting that the calendar by which my local church judges time should come from a place that deals with the intimacies of death. “So teach us to number our days,” prayed the great prophet Moses in Psalm 90, “that we may get a heart of wisdom” (Psalm 90:12).1 The request lies at the center of his meditation on the impermanence of the creature compared with the everlasting power of God. Our days end “like a sigh” (Psalm 90:9), they are “soon gone and we fly away” (Psalm 90:10). For modern people striving to separate themselves from any sign of death, it might seem morbid to ask God to show you how short your life will be.

Worse, for many people — the young mother cooking yet another meal, those suffering chronic health conditions, the increasing number of people enduring mental and emotional anguish — the effort of “numbering” days might feel cruel. I get up and do the same set of tasks over and over — bathing, eating, working — only to do it all again tomorrow. I kick against these cyclically monotonous goads. I should be going somewhere, accomplishing something, or — that most elusive hope — flourishing.

Is there a way out of the drudgery? The simple answer is yes — by considering the day of your inevitable death. But how can you do that? By following the church year in the company of other believers. In other words, by going to church.

The Journey: What Sunday Is It?

“This day shall be for you a memorial day, and you shall keep it as a feast to the Lord; throughout your generations, as a statute forever, you shall keep it as a feast.” (Exodus 12:14)

The heart of the church year is the life, death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus. You wouldn’t get out of bed and drag yourself to a gothic cathedral or a school cafeteria church plant to be with other Christians if Jesus hadn’t been born and died and risen again. The work of celebrating His life — from the time you are born until the time you die — is the spiritual backdrop, the practical meditation on that difficult line from Moses’ psalm: “For a thousand years in your sight are but as yesterday when it is past” (Psalm 90:4). God isn’t inside of time, but He entered into it by becoming a man and taking on our infirmities and troubles.

Those troubles rose to a fever pitch thousands of years before He was born. Pharaoh, bitterly stubborn to the end, finally gave up and let the people of Israel go. His land in ruins, the elusive prize of enslaving Jacob’s descendants fell from his grasp. In one swelling movement of time and eternity, God restarted the calendar and oriented the life of His people toward the coming Promise who would rescue them not only from drudgery but from the bondage to sin and death: “The Lord said to Moses and Aaron in the land of Egypt, ‘This month shall be for you the beginning of months. It shall be the first month of the year for you’” (Exodus 12:1).

Centuries later, it didn’t take the early church long to understand that the Passover of the Lord was always pointing, year by year, feast by feast, to the fulfillment of God’s promise for salvation and rest. On that very feast, at the hour the memorial lambs were being slaughtered, Jesus gave Himself up to die for us. And then, when He rose from the dead, that Sunday became, by dint of straightforward biblical reasoning, “the Lord’s Day” (1 Corinthians 16:1–2; Revelation 1:10). Our Lord stepped out of His tomb in the first light of that dawn, and again, the world adjusted its calendars. That became — for us — the first year, the focal point of our redemption.

This is why in my Sunday school I take out a puzzle called the Liturgical Calendar and dump all the pieces on the floor. I sit there and prompt the children to put the little wedges into their grooves in the proper order. “What goes first?” I ask. They pick out four little pieces of painted wood. Then I stop and correct myself. “Oops,” I say, “we should have done the Feasts first.” There are three — Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost. We slot them in and add the four blue (or purple) for Advent, the six purple for Lent, the seven white Sundays of Easter, and then all the green ones for Ordinary time. Each of the 52 weeks takes its place in a strange union between the circle of the seasons and the progression of time toward Christ’s return to judge the living and the dead.

The Destination: The Hope of Our Salvation

“By faith Abraham obeyed when he was called to go out to a place that he was to receive as an inheritance. And he went out, not knowing where he was going. By faith he went to live in the land of promise, as in a foreign land, living in tents with Isaac and Jacob, heirs with him of the same promise. For he was looking forward to the city that has foundations, whose designer and builder is God.” (Hebrews 11:8–10)

In the same way that the church quickly discovered that the Passover was the foreshadowing of the cross, Abraham’s exile from his home country to sojourn in the land of promise — a type recapitulated through the Old Testament — finds its true fulfillment in Jesus’ earthly life. He leaves His Father’s side and comes to a strange people in a strange land. He comes to claim an inheritance — a Bride for Himself. But then, as you repeatedly step across the threshold of your local church and go forward for communion, after hearing (hopefully) a clear explication of this very story, you discover that He is your inheritance. That journey — from unknown to known, from stranger to friend — is shaped by the cyclical study of Scripture throughout the year.

That study begins every year with one of the three synoptic Gospels woven together with the Old Testament prophecies of Christ’s birth, a whole month before January.2 By Christmas, though the year is yet young, I am already worn out by the Christmas Pageant, a raucous affair of kid shepherds with sticks and wandering toddler sheep.3 If I survive the Pageant, I have eight (and twelve) whole days of feasting. Some theologians believe the Octave of Christmas — originally incorporating the feast days of St. Stephen, St. John and St. James, St. Paul and St. Peter — was adapted from the Maccabean memorial of Chanukah.4 Technically, you shouldn’t even begin to think of fasting until after February 2, the feast of Jesus’ dedication. That long season of rejoicing, however, is only a shadow of the holiest three days of the year, Maundy Thursday through Easter Sunday. Through the stripping of the Lord’s Table to its festal adornment with lilies and candles, you could tell the story of salvation in the past tense. It did happen. But the point is that it is shaping — in the present tense — every part of how you live in time. In the way the “Hall of Faith” in Hebrews 11 surprises new Christians toiling their way through the Old Testament — all these people seemed like doubting sinners, they complain — the crushing darkness of Good Friday always perplexes me. How could God submit Himself to the degradation of the grave? The answer is given every single Sunday in the halting, anxious joy of the resurrection.

The Friends You Make Along the Way: Learning to Be Homesick

“How lovely is your dwelling place,

O Lord of hosts!

My soul longs, yes, faints

for the courts of the Lord;

my heart and flesh sing for joy

to the living God.

Even the sparrow finds a home,

and the swallow a nest for herself,

where she may lay her young,

at your altars, O Lord of hosts,

my King and my God.”

Psalm 84:1–3

On the night before He died, Jesus gathered His twelve disciples in the Upper Room and instituted the Eucharist — the Lord’s Supper. In some fifty days, they would emerge from that same room as giants of faith, apostles equipped to establish the church. That evening, though, it felt like their friend was abandoning them. Jesus comforted them with these words: “Do not let your hearts be troubled. You believe in God; believe also in me. My Father’s house has many rooms; if that were not so, would I have told you that I am going there to prepare a place for you? And if I go and prepare a place for you, I will come back and take you to be with me that you also may be where I am” (John 14:1–4).

All around the Temple, so familiar to the beleaguered twelve, were useful rooms for the work associated with worship. Probably the High Priest in the time of Josiah found the Bible moldering in one such room (2 Kings 22:8–10). It could be those kinds of rooms that Jesus had in mind when He said, “My Father’s house has many rooms.” Others believe He was referring to the practical arrangements of marriage in the first century. A man would “build a room” in his father’s house. No guest room for a stranger, nor a closet to store junk, but a comfortable place to live with the people you love best — your wife and your parents. This might not seem very appealing to Christians today, but it serves as a useful paradigm for how to think about the church.

A spiritual community of people toiling through the church year is going to do a lot of worshiping and working together. They are going to eat meals in a room echoing with the shouts of children running in spite of repeatedly being told to walk. They are going to have to dust and vacuum their sanctuary. They are going to want technology of some kind to keep up with each other during their times of separation (the work week). They are going to want to be reverent, but also “at home” in the space they weekly gather.

The whole church together is the Bride that Christ purchases for Himself on the cross. There is, therefore, enough room for the whole mystical body of his faithful people — toddlers, tweeners, snowbirds, able, infirm, functional, dysfunctional, confused. If they, together, begin to think about their lives as a sojourn in the wilderness on the way to the Promised Land, rather than a time to work through their bucket lists, they will gradually shift their expectations of churchgoing. Rather than one activity among many as time allows, going to church is like living in a little room appended to the temple, or a house in the family compound, or a tent sloping away from the Tabernacle in the shadow of Sinai. The rhythm of their lives is determined by the inclinations and habits of the worshiping community. That community won’t be people they pick for themselves among their favorite TikTok followers. Rather, they will be people God places as burdens on their weary minds, as part of their heavenly inheritance.

For people living in a modern technoscape, this should feel like stepping into another world. When the local church gathers for prayer, worship, study, and meals, you’re going to want to try to figure out how to be there. Sometimes you won’t be able to, in which case you might feel a vague sense of bereavement, if not actual fear of missing out. When you do make it, your children — go ahead and think of all the children in the building, whomever they belong to, not as annoyances, but as interesting Christian people — will spread out to find their friends, with barely a backward glance. When you leave you will not often feel lifted up into some spiritual ecstasy. You will feel just as tired and downcast as when you went in. That is because the mystery of Christ’s body is revealed in the difficulties of each other’s lives, the desperate prayer for people you don’t feel like you know well enough.

Take the Free Calendar

“Satisfy us in the morning with your steadfast love,

that we may rejoice and be glad all our days.

Make us glad for as many days as you have afflicted us,

and for as many years as we have seen evil.

Let your work be shown to your servants,

and your glorious power to their children.”

(Psalm 90:14–16)

Everyone has to follow some kind of calendar. If you’re not following along with the life and death of Jesus, you might find that the commemoration of Valentine’s Day and the summer movie blockbuster season are the depth and breadth of your relationship with Jesus. If you don’t follow the appointed lectionary readings that go along with the liturgical calendar, the Scripture readings of your church might be chosen at random according to the inclinations of the pastor or elder board. You might arrive on Easter Sunday morning to hear a sermon on a text taken from Leviticus, rather than John 20. Many faithful churches fall into this category. But without a calendar for the church year, over time the congregation might lose track of the expectations Jesus sets out for His followers — to conform their lives to His. Ordinary Christians lose the practical ability to “number their days” when they rush from the last secular festival to the latest Christian fad. They aren’t anchored spiritually in the very reason for which Jesus joins individual people together in the church — to make his Bride comfortable in the home He is preparing for her.

It is almost impossible to accomplish this anchoring rhythm on your own without the help of an actual in-real-life group of people who are also trying to bend themselves to the strange pleasures of that other home. I have noticed a deep dissatisfaction grow in those who try to follow the church year in isolation away from a church body. Can you do it? Of course. But you might not want to try because it will set the most basic elements of your life in opposition to the local body.

Fundamentally, when you walk into a room filled with other Christians, however sad or anxious you are, you gradually want to feel the deep gladness of God’s favor in the peculiar communion of those particular people. Only God has the power to confer that gift. He accomplishes it when you submit yourself to the work and worship of a distinct, local body. If the Scriptures are the bedrock of that body, the cornerstone, the sure foundation, whatever their special days, their feasts and fasts, the Christian’s obedient gladness in that community will lighten the way and make the long journey seem much, much less than a thousand years.

Anne Kennedy, MDiv, is the author of Nailed It: 365 Readings for Angry or Worn-Out People, rev. ed. (Square Halo Books, 2020). She blogs about current events and theological trends at Standfirminfaith.org.

NOTES

- All Scripture quotations are from the English Standard Version. A little searching reveals that most articles on the subject of the church year begin with Psalm 90:12. My favorite is one by J. Brandon Meeks in The North American Anglican called “A Cruciform Calendar,” November 18, 2019, https://northamanglican.com/a-cruciform-calendar/.

- Arguments over the date of the birth of Christ continue apace. Brandon LeTourneau points to evidence that early Christians took the date of Jesus’ birth from a prophecy in Haggai 2:18–19. His December 18, 2022 piece in the The North American Anglican, “The Feast of Dedication: Christians and Chanukah,” is a fascinating work of liturgical archeology, https://northamanglican.com/the-feast-of-dedication-christians-and-chanukah/.

- The Christmas Crèche first appeared in Christian history in the time of St. Francis. St. Bonaventure, writing about the life of Francis describes the rather fantastical scene. “Francis and the Crèche,” Franciscan Friars Conventual, https://www.franciscans.org/single-post/2017/12/20/Francis-and-the-Cr%C3%A8che.

- LeTourneau, “The Feast of Dedication: Christians and Chanukah.”