Listen to this article (15:07 min)

Cultural Apologetics Column

This article was published exclusively online in the Christian Research Journal, Volume 47, number 04 (2024).

When you support the Journal, you join the team and help provide the resources at equip.org that minister to people worldwide. These resources include our ever-growing database of more than 2,000 articles, as well as our free Postmodern Realities podcast.

Another way you can support our online articles is by leaving us a tip. A tip is just a small amount, like $3, $5, or $10, which is the cost of a latte, lunch out, or coffee drink. To leave a tip, click here.

Television Series Review

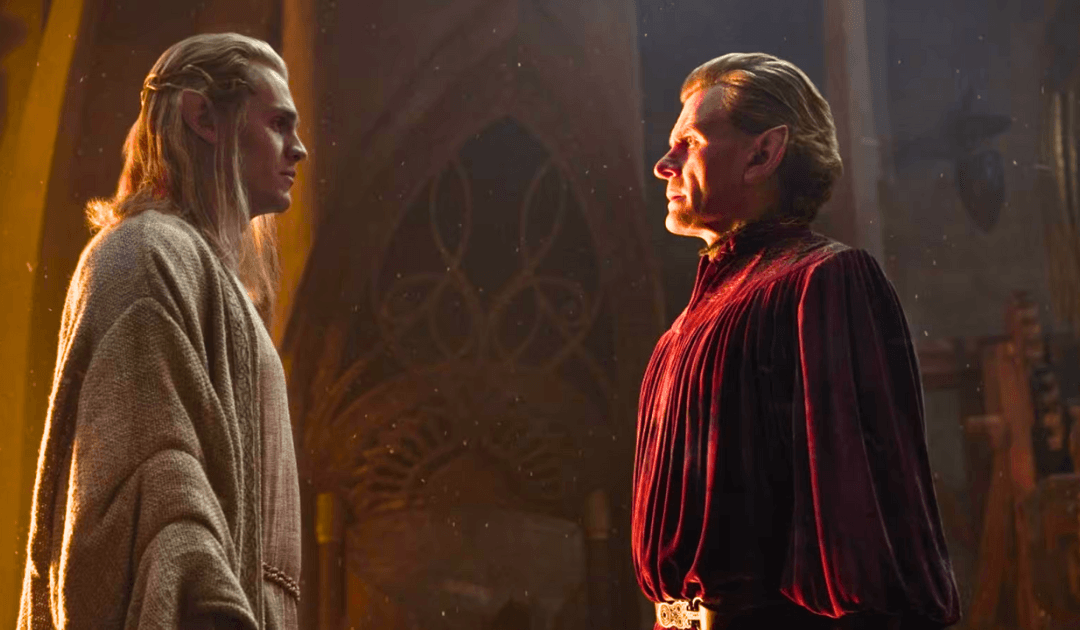

The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power (Season Two)

Developed by John D. Payne and Patrick McKay

Executive Producers: John D. Payne, Patrick McKay, Christina Morgan, Lindsey Weber, Callum Greene, Justin Doble, Gennifer Hutchison, Jason Cahill, J. A. Bayona, Belén Atienza, Eugene Kelly, Bruce Richmond, and Sharon Tal Yguado

Producers: Ron Ames, Chris Newman, Kate Hazell, and Helen Shang

Amazon MGM Studios & New Line Cinema

Streaming on Amazon Prime Video

(Rated TV–14, 2022–)

[Editor’s Note: This article contains spoilers for The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power.]

“Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.”1 This famous quote, attributed to Lord Acton, could just as easily serve as the thesis statement for the sophomore season of Amazon’s streaming hit, The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power (2022–). Further exploring the Second Age of Middle-earth, the allure and peril of unchecked power and untempered ambition become inevitable thematic focal points this season, as the series inches us closer to Tolkien’s legendary trilogy.

In the first season, the groundwork was laid as characters such as Galadriel (Morfydd Clark), Elrond (Robert Aramayo), and the enigmatic, shape-shifting Sauron (Charlie Vickers) grappled with their own ambitions and motivations. That season concluded with the creation of the first rings of power under the watchful eye of the Elven smith, Celebrimbor (Charles Edwards).2 The desire to forge something eternal that could perhaps defy time and mortality as the Elven races began to fade from the annals of history was at the heart of Celebrimbor’s endeavor in Eregion. Yet, as Acton’s words suggest, even the noblest intentions can quickly become tainted by the corruption that power brings.

One of the most compelling aspects of the recent season is its focus on the power of suggestion and manipulation. Sauron is a master of deceit, poised to play perhaps the most important role in shaping the fate of Middle-earth. His ability to influence the hearts and minds of even the wisest and most powerful among the Elves, such as Galadriel, was showcased in the first season. The second season explores this dynamic in even greater detail, alongside Sauron’s ability to shapeshift. This is seen most obviously in his manipulation of Celebrimbor under the guise of Annatar, Sauron’s “fair form,” in which he presents himself as a messenger of the Valar — the Powers of the World in Tolkien’s legendarium, who govern the world in subordination to Eru Ilúvatar.3 Through whispers and half-truths (and no small amount of what the kids today call “gaslighting”),4 Sauron compels Celebrimbor to carry out the smithing of rings for the free peoples of Middle-earth: Elves, Dwarves, and Men.

The season also explores the ambition of Númenor, the mighty island kingdom of Men, where Queen Regent Míriel (Cynthia Addai-Robinson) and Pharazôn (Trystan Gravelle) vie for control of the throne. The downfall of Númenor, foreshadowed in the first season, is perhaps Tolkien’s most tragic tale — one in which a nation’s lust for power leads to its utter destruction. Similarly, in Khazad-dûm, the Dwarves’ pursuit of Mithril sees what begins as a desire to strengthen their realm and secure its future unravel as King Durin III (Peter Mullan) begins a slow descent into madness, having come to possess one of the titular rings.

Absolute Power. Tolkien’s work is often read as a cautionary tale about the dangers of power, pride, and unchecked ambition.5 Central to his narrative ethos is the idea that power, when divorced from wisdom and, most importantly, humility, becomes a corrupting force. Though The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power is an adaptation, it faithfully carries forward the essence of this idea, portraying ambition as a double-edged sword, and demonstrating how well-meaning but thoughtless actions can pave the way to ruin.6

This is most evident in the story of the rings themselves, where Sauron — in his role as Annatar, the “Lord of Gifts” — uses persuasion and half-truths to prey upon the desires of others, bending them to his purpose, rather than imposing his will outright. The tragedy of it all is that the ambitions he preys upon — whether it’s Celebrimbor’s desire to preserve the Elven legacy, Durin’s wish to secure Khazad-dûm’s prosperity, or even the Númenóreans’ yearning for immortality — are, on the surface, understandable, relatable, even noble. And the genius of Tolkien’s original work lies in showing the ease with which noble intent can become something much darker and far more sinister when humility and wisdom are tossed aside in the name of progress.

Within this framework, The Rings of Power takes special care to highlight a particular motif recurrent in Tolkien’s work: evil rarely forces — it invites, it tempts, it corrupts. The bitter realization that one’s own choices have led to a destruction, that none of it ever had to be, but for a precious few, seemingly innocuous compromises of moral character which cumulatively constitute the great knife that evil — indeed, that sin — wields. It chips away at, breaks down, one’s fortitude, ensuring that one reaches the conclusion that the “bad ending” is the inevitable one; and Sauron — like Satan — waits until one has nothing left and reaches such a conclusion before offering them the world (for a picture of this, see the way Satan tempts the Christ in Matthew 4). And the solution Sauron offers to Celebrimbor’s fears of decay and decline is tantalizingly practical: save the Elven races, save the mortal men “doomed to die,” all it takes is one more transgression, one more ring-forging. If only Celebrimbor had overcome his pride to surpass Fëanor, forger of the Silmarils, as the greatest of all Elven smiths, he might have rebuffed Sauron, as there was never any direct coercion; at least, not at first. Indeed, Sauron never overtook the great Elf’s will — nothing Celebrimbor did was something he did not actively choose or desire to do. Even in the end, Celebrimbor admitted to Galadriel that he had always sensed that something was wrong with Annatar — had always known better.

Tolkien’s own skepticism of power can be traced to his experiences. A veteran of the First World War and a witness to the rise of fascism throughout Europe, his experiences were fairly standard for those in similar positions in his generation. Much ink has been spilled over the way Tolkien’s wartime experiences influenced his writing, and there’s something to be said for keeping the author grounded in his historical context.7 However, Tolkien’s deep mistrust of any force that sought to dominate rather than nurture cannot be separated from his Christian faith — and Tolkien himself believed the fact that he was a Christian could actually be deduced from the stories he wrote.8

The Devil and Old Tom. For Tolkien, the rejection of power is as crucial as its use — which brings us to a character who was notoriously absent fro1 m Peter Jackson’s film trilogy (2001–2003): Tom Bombadil. In Tolkien’s world, Tom Bombadil is a bit of a question mark. One of the few characters in the novels to be completely untouched by the power of the One Ring, he is a singular figure seemingly immune to the ring’s corrupting influence, capable of handling it without fear or desire.

In The Fellowship of the Ring (1954), when Frodo Baggins offers Tom the ring, Bombadil examines it with casual disinterest, even making it disappear for a moment in a bit of a parlor trick. He then returns it, laughing, completely unperturbed by it. This is such a significant moment that stands out — shockingly so — because of how it starkly contrasts with every other character’s reaction to the ring, from Bilbo to Boromir to Gandalf, each of whom is gripped by either a primal fear or desire when faced with the ring’s presence.

Bombadil’s seeming immunity to temptation underscores a key point in Tolkien’s theology: that power is not about domination, possession, or control; rather, it is about contentment, and that there are good things in the world which lie beyond evil’s reach. But those good things are not found in the halls of kings or in the magic of wizards or in the might of heroes — all of whom are bent to the will of the ring. No, those good things are found in the “meat and potatoes” of life, the small, simple things that tend to be taken for granted: a cozy home, uncomplicated work with one’s hands, an easy meal with friends. When Frodo asks if Bombadil could keep the ring safe, Gandalf’s response is telling: Bombadil would forget about it, or simply not care. He is utterly detached from the ring’s influence because he does not covet — his life is one marked by simplicity and humility, and his very existence refutes Sauron’s core belief: that all things can be bought, controlled, or broken.

The recent season of The Rings of Power finally gives Tom Bombadil his due. Wonderfully portrayed by Rory Kinnear, Tom appears as a wandering hermit with a sing-song voice and an inscrutable smile who stands apart from the growing darkness and intrigue. Because the nature of adaptation demands some narrative agency, his character here is tied into Gandalf’s storyline, though one gets the sense that his inclusion is more than a nod to Tolkien purists. He functions as a “bright spot” in a dark story, and one hopes that the showrunners continue to utilize Kinnear’s fantastic take on Bombadil as the ultimate rejection of evil by being beyond its reach altogether.

An Apologetic Trove. If one can look past the compressed timeline and slight alterations to Tolkien’s established mythology for the sake of adaptation, the cultural apologist can find in this recent season of The Rings of Power a valuable tool for engaging in meaningful conversations about faith. One of the most effective “on ramps” for these conversations is Sauron’s corrupting influence. His methods mirror the biblical description of Satan as the father of lies (John 8:44), the deceiver who twists the truth. Time and again we see in Scripture the subtle nature of evil, how it presents itself as a reasonable solution or a path to temporal greatness, only to ensnare those who seek it — consider King Saul, proud of heart (1 Samual 13–15), or the wisdom of Solomon when he writes, “When arrogance comes, then comes disgrace, But with the meek is wisdom” (Proverbs 11:2 LSB).

The inclusion of Tom Bombadil also opens up some distinct avenues for theological reflection. His carefree joy and immunity to the darkness represents a radical alternative to typical responses to evil. Tolkien’s insistence that humility is the antidote to corruption is personified in Bombadil’s contentment with his small realm and simple life, untouched by the need for dominion or control. This can raise some interesting questions about what true “strength” looks like — and the apostle Paul (while sitting in prison, mind you) provided some interesting (if antithetical) commentary on that in Philippians 2–4.

As a Tolkien reader, I will forego most of my personal gripes with The Rings of Power here to say that the show’s sophomore season works much like the first — as an accessible means for the cultural apologist to introduce and explore the Christian faith in everyday conversation. But, on the off chance that one of the executive producers or showrunners or somebody with a dog in the fight putters along and reads this and wants to know what I think, suffice to say these three things: 1) whoever told Nori to take a hike in favor of Kinnear’s Tom Bombadil should get a raise; 2) have a conversation with your writers’ room (or your editor, whichever is appropriate) about Arondir’s miraculous healing abilities — he was really stabbed, and then he was really okay, and it made no sense whatsoever; and 3) take this as a lesson that your “original” characters were unnecessary in the first place, because now it just looks like nobody in the writing room knows what to do with them, so they keep getting juggled around and shunted awkwardly into Tolkien’s already fine story — the compression of which I do not mind because it is actually hard to write a good adaptation.

In other words: give us more Old Tom (preferably singing) — Kinnear is great, and with Bear McCreary helping him, it’s magic. Let. Them. Cook.

Cole Burgett is a graduate of Dallas Theological Seminary and the Moody Bible Institute. He teaches classes in systematic theology and Bible exposition and writes extensively about theology and popular culture.

NOTES

- John Dalberg-Acton, “Acton-Creighton Correspondence” (1887), Online Library of Liberty, accessed October 14, 2024, https://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/acton-acton-creighton-correspondence#.

- For coverage of the first season, see Cole Burgett, “Tolkien Reimagined: A Series Review of The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power,” Christian Research Journal, November 15, 2022, https://www.equip.org/articles/tolkien-reimagined-a-series-review-of-the-lord-of-the-rings-the-rings-of-power/.

- For a decent primer on the Valar, see Michael John Petty, “Who Are the Valar in ‘The Rings of Power’ Season 2,” Collider, August 30, 2024, https://collider.com/rings-of-power-season-2-valar-explained/.

- “Gaslighting” has been defined as “an insidious form of manipulation and psychological control [in which] victims…are deliberately and systematically fed false information that leads them to question what they know to be true, often about themselves.” The term comes from the iconic 1944 film, Gaslight, and the tremendous 1938 play on which it was based — though it seems that many who throw the term around today are unaware of its origins. For more details, see “Gaslighting” Psychology Today, accessed October 14, 2024, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/basics/gaslighting. See also Anne Kennedy, “For Our Lamps Are Going Out: Gaslighting in the Age of Social Media,” Christian Research Journal, September 29, 2021, https://www.equip.org/articles/for-our-lamps-are-going-out-gaslighting-in-the-age-of-social-media/.

- This interpretation of Tolkien’s work was literally the subject of a recent episode of the podcast Cautionary Tales with Tim Harford. See “Cautionary Tales — Tim’s Tolkien Obsession and Amazon Prime’s ‘The Rings of Power,’” Tim Harford, August 30, 2024, https://timharford.com/2024/08/cautionary-tales-tims-tolkien-obsession-and-amazon-primes-the-rings-of-power/.

- Brett McCracken at The Gospel Coalition helpfully characterizes the rings as “stand-in” for “the corruptions of power, the temptations of pragmatism, and the perils of bypassing the ‘right way’ in favor of ‘the fast way,’” suggesting that the rings function “like Eden’s forbidden fruit” in that “they also bring death.” Brett McCracken, “‘Rings of Power’ Season 2: Getting Better, Still Flawed,” The Gospel Coalition, August 29, 2024, https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/article/rings-power-season-2-review/.

- See Rachel Kambury, “War Without Allegory: WWI, Tolkien, and The Lord of the Rings,” U.S. World War One Centennial Commission, accessed October 14, 2024, https://www.worldwar1centennial.org/index.php/articles-posts/5502-war-not-allegory-wwi-tolkien-and-the-lord-of-the-rings.html.

- For an excellent and thorough book on the subject, see Holly Ordway, Tolkien’s Faith: A Spiritual Biography (Elk Grove Village, IL: Word on Fire Academic, 2023).