Note: This is part of our ongoing Philosophers Series.

When you to subscribe to the Journal, you join the team of print subscribers whose paid subscriptions help provide the resources at equip.org that minister to people worldwide. These resources include our ever growing database of over 1,500 articles, as well as our free Postmodern Realities podcast.

Another way you can support our online articles is by leaving us a tip. A tip is just a small amount, like $3, $5, or $10 which is the cost for some of a latte, lunch out, or coffee drink. To leave a tip, click here

SYNOPSIS

Choices, mundane and consequential, are made by employing decision-theoretic reasoning. Odds, stakes, risk, cost, and benefit are weighed in concurrence to determine the most prudent course of action. Sometimes available evidence guides the decision. Other times the choice falls to guess work or personal preferences. Biblical Christianity offers two options: follow Jesus and gain life, or reject Him and lose your soul. When considering decisions of eternal magnitude, agnosticism is not a viable option. Action must be taken.

Blaise Pascal famously asked his audience to wager on God. He reasoned that if it turns out God does not exist, the worst that could happen to the wagerer is a few minor inconveniences in this life. To wager against God and possibly lose everything is a risk no rational person should be willing to take. I argue that centuries before Pascal made his wager, Jesus gave a similar but higher stakes wager when He asked His disciples to take up their cross and follow Him. Jesus raised the stakes by pointing to the inevitable suffering that would accompany discipleship. In asking His audience to forsake the world and follow Him, Jesus made the wager more tangible, pointing to Himself and the benefits of knowing Him as the ultimate reward. I offer that Pascal’s and Jesus’ wagers, when taken together, form a rational prudential incentive to accept the fundamental tenets of Christian belief.

Most people employ decision-theoretic reasoning on a near daily basis. Choices, both meaningful and mundane, are subjected to extemporaneous, if not mechanical, analysis. Probabilities, costs, risk, and benefits are filtered and weighed against wants, needs, fears and dreams. Consider an example: “If I leave for work now, I will not have time for breakfast, but I might avoid bad traffic. However, if I take time to eat, I might be late for work. Furthermore, if I forego breakfast, I will lack energy and perform poorly. Should I take time to eat?” Or another example: “Should I take an expensive cruise for my vacation? If I do, I may not have enough money to pay for the basement remodel I have wanted to do for years. But I really need a break. Which is more important? Which will garner greater long-term satisfaction? Can I do both?”

These examples represent trivial cases of decision-theoretic reasoning. Many quotidian and mundane decisions require at least a minimum of cost, benefit, and risk analysis. It is common to give pause to daily routine decisions as we weigh how choices affect finances, relationships, and time commitments. How much more, then, should we weigh the decisions of eternal consequence? In his wager argument, Blaise Pascal laid the magnitude of eternity in full view of his 17th century agnostic peers. Pascal reasoned that, when evidence for God is inconclusive to an individual, it is better for that person to wager on belief and the possibility of eternal life than to wager on disbelief and risk eternal damnation. In this way, eternity may hinge on the flip of a coin — a gamble on God.

Pascal’s wager is an attempt to convince the agnostic of the eternal advantages of belief. Unbeknownst to him (he died before his wager argument was published), Pascal made gambling on God a subject of discussion and controversy among philosophers and theologian for centuries to come. But long before Pascal extended his prudential offer to his skeptical peers, Jesus made a similar offer: Better to trust me, deny yourself, and gain life than to pursue the world and forfeit your soul (see Matt. 16:24–26).

In His wager, Jesus asks His listeners to weigh the value of His cross against the value of the world. Two ways are revealed: life and death. An invitation is given: forsake the transient and pursue the eternal. Jesus’s wager, as I shall call it, bears some important similarities to that of Pascal’s. With this in mind, I will argue two things: 1) that in applying decision-theoretic thinking about Christian truth claims, it is not irrational to trust in Jesus — that is, to make a reasoned wager on Jesus, and 2) that wagering on Jesus is more than a mere intellectual exercise or coin toss; it is a life-changing relationship rooted in the reality of who Jesus is and what He has done. To cast our lot with Jesus is to lean on a promise amplified by His resurrection and verified by the witness of Scripture.

Pascal’s Wager

A comparison of these two wagers is in order. Pascal’s application of decision-theoretic analysis in his wager argument is recognized as an important, if not notorious, contribution within the history of Christian apologetics. Pascal argued that in the absence of a convincing proof for theistic belief, the agnostic should risk belief in the Christian God and gain eternal life, rather than deny Him and risk eternal punishment. In short, Pascal’s wager is not an argument for the existence of God, but for the rationality of belief in the existence of God.

In the Pensées, where Pascal discusses his wager between theism and atheism, he states that “by reason you can neither adopt one or the other; by reason you can defend neither of the two” (418/233).1 In using the term reason, Pascal clearly has in mind situations in which the evidence is insufficient for justifying belief.

Consider the argument as envisaged by Pascal:

God is, or he is not; to which side will we lean? Reason can determine nothing….You must wager. There is no choice, you have already begun. Which will you choose? Let us see, since we must make a choice. Let us see which one interests us the least. You have two things to lose: the true and the good, and two things to gain: your reason and your will, your knowledge and your happiness. Your nature has two things to avoid: error and wretchedness….Let us weigh the gain and loss of calling heads that God exists. Let us appraise the two options: if you win, you win everything, and if you lose, you lose nothing. Wager then that he exists without hesitation (418/233).

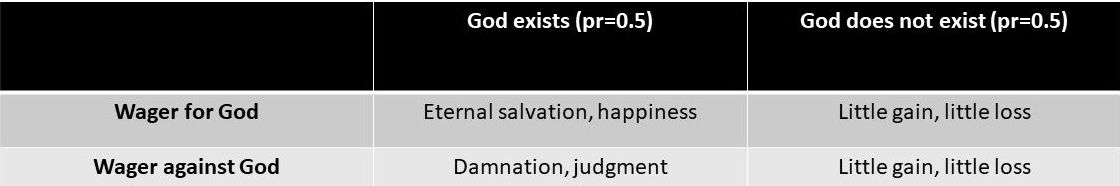

Note that the wager argument is constructed as a decision-theoretic gamble on God’s existence. To bet on God’s existence is to adopt the cognitive attitude that He exists, and to believe that if He does, momentous reward will be gained. To erroneously bet on God’s existence is to lose little or nothing. In contrast, a misplaced bet in favour of atheism may yield momentous loss if it turns out that God does indeed exist. For Pascal, the prudential response is clearly that of the safest bet: God exists. In Table 1, the existence of God has a 50 percent probability (pr=0.5). The stakes are high since eternity is on the line.

Table 1 — Pascal’s decision matrix

It is possible to read Pascal’s wager as an argument that develops in several steps. First, Pascal asks the wagerer to choose the dominant strategy. The wagerer is asked to perform the act that dominates between various acts in a set without consideration of probabilities. The dominating act is that which yields the best possible outcome (or utility) in a lottery scenario. According to Ian Hacking, the wager first considers which of two acts dominates the other, independent of probability assignments.2 The argument from dominance is concerned with the idea that if God exists, eternal salvation or infinite happiness ensues. Dominance alone should incline us toward a wager for God.

Second, Pascal examines expected utility. He offers a probabilistically calculated risk.3 Setting the probability of God’s existence at 0.5, Pascal likens his gamble to a coin toss. He is assuming indifference toward evidence in his probability assignment, rather than pointing to antecedent evidence that the coin is unbiased. It is worth noting that while an assignment of 0.5 probability seems arbitrary, evidential elements are not considered in this stage of Pascal’s apologetic. Letting the wager stand on its own merit, he says that he “ties his hands” and asks us to imagine that evidential considerations are moot in assigning probability to God’s existence.4

Third, it can be reasoned that if probability assignment and expected utility converge to dominate other acts in a state of affairs, dominating expectations should be taken into account.5 Dominating expectations considers the overall probability assignment for God’s existence. By Pascal’s reasoning, and as noted above, the probability of God’s existence has an arbitrary assignment of 0.5. Such clean odds are hardly realistic, but the beauty of Pascal’s Wager is that by assigning infinite reward to a successful wager on God’s existence, and setting the stakes low, the wagerer on God is in a position to win big. The argument from dominating expectations states that even a terribly low non-zero probability of God’s existence is not enough to dissuade a wager for God if the expected utility remains high or tends toward infinity.6 As long as the reward is momentous, and the cost to the wagerer low, a pro-theistic wager on a non-zero probability of God’s existence seems most prudent.

It is debatable whether Pascal intended three separate arguments, or whether his reasoning serves to demonstrate the careful progression of his argument by way of intermittent steps.7 Either way, the wager is susceptible to several noteworthy objections. The popular many-gods objection asks why we should be inclined to wager on the God of the Bible when myriad other gods might be considered. To this, it suffices to remind the objector that Pascal’s wager was offered to 17th century Frenchmen in an almost exclusively Roman Catholic context.8 The point of the wager is to address epistemic options that are most tenable to the agnostic in question. Though Pascal briefly addresses Islam in his apologetic writings, Judeo-Christian theism seems to be his primary concern.

The moral objection questions the intellectual virtue of gambling with something so sacred as human beliefs, particularly the belief in a putative creator and lord of the universe. This concern, however, may be abated if we take the position that Pascal offers a wager only when no other apologetic for the Christian faith has achieved its goal. The Pensées — a fragmented, yet thorough treatment of the cogency of the Christian worldview — examines human nature and suggests the biblical account of creation, fall, and redemption as the best explanation of anthropology and theology. With this view in mind, it is not unreasonable to take the wager as a last recourse — a final persuasive plea, rather than a careless intellectual lunge away from reality.

Other objections challenge the probability that Pascal assigns the existence of God, and the mathematical absurdity of infinity in the context of a wager. The swamping objection states that since the offer of an infinite reward creates a mathematically absurd calculation (infinity times any probability assignment is still infinity), the merits of a wager on God cannot be realistically calculated. For example, most rational people would hold that a $1 stake on a 25 percent chance of winning $1000 is a better gamble than a $1 stake on a 75 percent chance of winning $2. Odds and winnings are weighed together. But how are we possibly to calculate infinity in relation to any odds? The immeasurable reward of infinity for belief in God, even when calculated in terms of an infinitesimally small probability of God’s existence, still comes out as infinity and swamps any calculation against God no matter how high the probability against Him. One one-millionth of a percent multiplied by infinity equals infinity, meaning that mathematically we should take the bet despite terrible odds.

To answer the swamping objection one must simply modify the value assignment of the reward. Infinity can easily be replaced with a momentous yet finite number, thus making the math work out. Instead of infinite reward, the wagerer might gain, say, one million units of happiness or some other large but arbitrary measurement of recompense. A modification to the reward for belief in God would allow a reasonable probability calculation to be made and measured against the alternatives.

This sampling of objections demonstrates that Pascal’s wager is not without its problems.9 But let us not forget the purpose of the wager. Pascal’s intent was to ask his peers what the wisest course of action might be when confronted with the possibility of the existence of a holy, eternal creator God. Pascal’s aim was not to invite belief despite evidence to the contrary. His objective was to make the agnostic squirm in his complacency when faced with the most important matters in life. The wager was an invitation to step out of the gloom of unproductive doubts and into the light of Christian belief.

Jesus’ Wager

Centuries before Pascal’s wager stirred debate among philosophers and theologians, Jesus made a similar case for belief. He asked His disciples to choose whom they would serve. Matthew 16:24–26 recounts the words of Jesus:

If anyone would come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross and follow me. For whoever would save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for my sake will find it. For what will it profit a man if he gains the whole world and forfeits his soul? Or what shall a man give in return for his soul?10

Like Pascal, Jesus invites a decision. Unlike Pascal, Jesus raises the stakes by promising difficulties and trials to anyone who casts his lot with Him. The decision is not straight-forward. No matter where the bet is placed, there is something to be gained and something to be lost. In this way, eternal life may not necessarily seem appealing when the wagerer is faced with the immediacy of self-denial, abandonment of earthy pleasures, and the physical suffering represented by a Roman cross. Conversely, self-affirmation and earthy pleasure may appear exceedingly attractive when the eternal state of the soul after death can seem to be a distant and abstract concern.

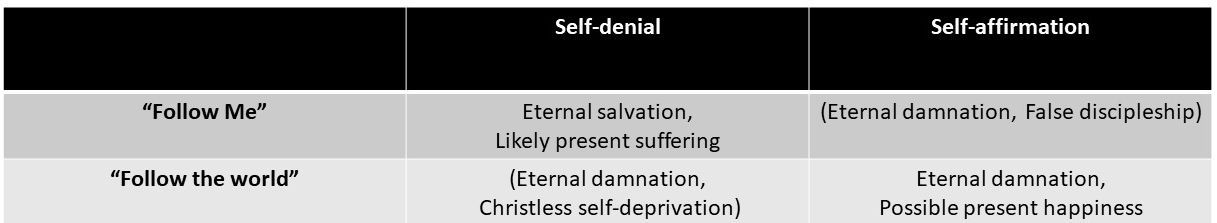

The decision-theoretic reasoning invited by Jesus’ wager is slightly less complex than that of Pascal. Only two real options are explicit in the text. In Table 2, the first option is “follow me” + self-denial = eternal salvation and likely present suffering. The second option is “follow the world” + self-affirmation = eternal damnation and possible present happiness. The decision matrix represented in Table 2 was constructed to also include two other possible outcomes implicit in Jesus’ teaching throughout the gospel accounts. These involve false discipleship and self-worship. We will not discuss them at present. The point to be considered here is that Jesus does not mince words. There is only one choice that can end well: follow Jesus at all costs and with an unwavering devotion.

Table 2 — Jesus’ decision matrix

Jesus’ wager is a prudential offer in that it asks us to give up something of value for the promise of something of even greater value. But is Jesus’ wager a true wager in the decision-theoretic sense elaborated by Pascal? There are some notable differences between the two. Where Pascal asks the wagerer to gamble belief on God, in a general kind of Christian theism, Jesus asks His disciples to wager a close relational bond with himself — God in the flesh, the promised Messiah. For Jesus, neither the object of belief nor the reward for believing are presented as distance abstract realities. For the disciples, the reward was standing right there in front of them. Jesus Himself would return in glory. Jesus Himself would repay each person according to what he had done.

Another difference between the two wagers is seen in how dominance, utility, and expectation are measured in Jesus’ invitation. Jesus’ wager lacks a probability assignment. He assigns no odds. Rather, He offers a guarantee — a promise that the outcome will be a certain way. Where Pascal gives 0.5 odds on a momentous reward, we might say that Jesus gives 1.0 odds on a mixed bag of momentous reward and significant momentary trials. At first blush, it seems that Jesus’ wager is less akin to a risky crapshoot, and more akin to a carnival game where everyone who gambles in favor of Jesus is a winner, though they might not like aspects of the prize.

The decision-theoretic reasoning one must employ in responding to Jesus’ offer hinges on how much of the present is to be risked in exchange for a glorious future. To some, the dominating strategy is clear: eternal bliss is worth a life of hardship. To others, no eternal promise is enough to entice forsaking an easy quiet life of simple pleasures and epicurean indulgences. Jesus asks His disciples, and every subsequent generation, to consider the value of their soul and whether they are willing to entrust it to Him.

The decision is not as easy as it may seem. How do I know I have an eternal soul? Who is Jesus that I should trust Him with my life? By what authority does Jesus claim He will reward His followers? How many other “messiahs” have come making empty promises of reward in exchange for loyalty? These are not trivial questions. Although answering them in depth is beyond the scope of this article,11 the historic eyewitness account of Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection in the Gospels corroborates His promise. If Jesus is who He says He is (John 14:6), who the Father says He is (Matt. 3:17), and who the prophets say He is (Isa. 53), then it is not irrational to wager on Him. If His death and resurrection are historic realities backed up by eyewitness testimony, then it is not irrational to wager on Jesus. If the Gospel accounts have accurately related how Jesus fulfills centuries of divine revelation, then trusting Jesus is more than a mere gamble; it is a conviction rooted in truth and capable of sustaining the believer through trials and hardships.

Wager or Promise

Pascal’s wager asks the gambler to take a step toward God. It is designed to invite a cognitive attitude of acceptance of the proposition that God exists. Pascal asks the gambler to give God a try — to accept the Christian God and see where it leads. Moreover, Pascal warns of the danger of rejecting God. Oddly enough, Jesus warns of the very opposite — the danger of accepting God. To walk with Jesus is to face the onslaught of the world, the flesh, and the devil (Eph. 2:1–3). Jesus asks His followers to count the cost and trust the promise. Intellectual acceptance of a cognitive attitude is not enough. Jesus wants heart, soul, mind, and strength (Mark 12:30). He wants us to know the risk of making Him our Lord, while receiving the benefits of the transformation and healing He offers (Rom. 12:1–2).

Notwithstanding the differences in their arguments, both Pascal and Jesus remind us that a gamble on God is a winning bet. The follower of Christ Jesus does not leave His destiny to the role of the dice or the fatalistic outcomes of a blind unthinking universe. The stars in their various alignments care nothing for humans. But the sovereign Creator of the stars does, as He orchestrates His plan of salvation in love, both in this life and in the life to come (Eph. 1:1–14). Whatever the risk, the cost, the odds, or the benefits, following Jesus is more than a gamble; it is a lifechanging relationship that begins here and now, and extends into all eternity.

Jonah Haddad (MA in Philosophy of Religion, Denver Seminary) is a researcher in epistemology through the University of Aberdeen, UK. He serves as an associate pastor in Colorado.

NOTES

- All citations from the Pensées are my translation, from the standard Louis Lafuma text Œuvres Complètes (1963).

- Ian Hacking, “The Logic of the Wager,” American Philosophical Quarterly 9.2 (1972): 187.

- See Nicholas Rescher, Pascal’s Wager: A Study in Practical Reasoning in Philosophical Theology (Notre Dame, IN: Notre Dame University Press, 1985), 33.

- Pascal, Pensées (418/233).

- See Hacking, Logic of Wager, 188.

- James Franklin suggests the notion of infinity be replaced by something momentous yet finite. See James Franklin, “Pascal’s Wager and the Origins of Decision Theory: Decision-Making by Real Decision-Makers,” Pascal’s Wager, ed. Paul Bartha and Lawrence Pasternack (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 27–44.

- Hacking thinks there are three arguments contained within Pascal’s text.

- Following the Protestant Reformation only a small percentage of Calvinists remained in France at the time of Pascal.

- Another objection asks whether it is possible to coerce belief. Some philosophers think it is better to use a weaker term, such as acceptance, rather than a weightier epistemic term like belief.

- Scripture quotations from the ESV.

- For a clear treatment of these questions, see Douglas Groothuis, Christian Apologetics: A Comprehensive Case for Biblical Faith, 2nd ed. (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 2022).