Listen to this article (13:06 min)

Cultural Apologetics Column

This article was published exclusively online in the Christian Research Journal, Volume 47, number 01 (2024).

When you support the Journal, you join the team and help provide the resources at equip.org that minister to people worldwide. These resources include our ever-growing database of more than 2,000 articles, as well as our free Postmodern Realities podcast.

Another way you can support our online articles is by leaving us a tip. A tip is just a small amount, like $3, $5, or $10, which is the cost of a latte, lunch out, or coffee drink. To leave a tip, click here.

[Editor’s Note: This review contains spoilers for Dune: Part Two.]

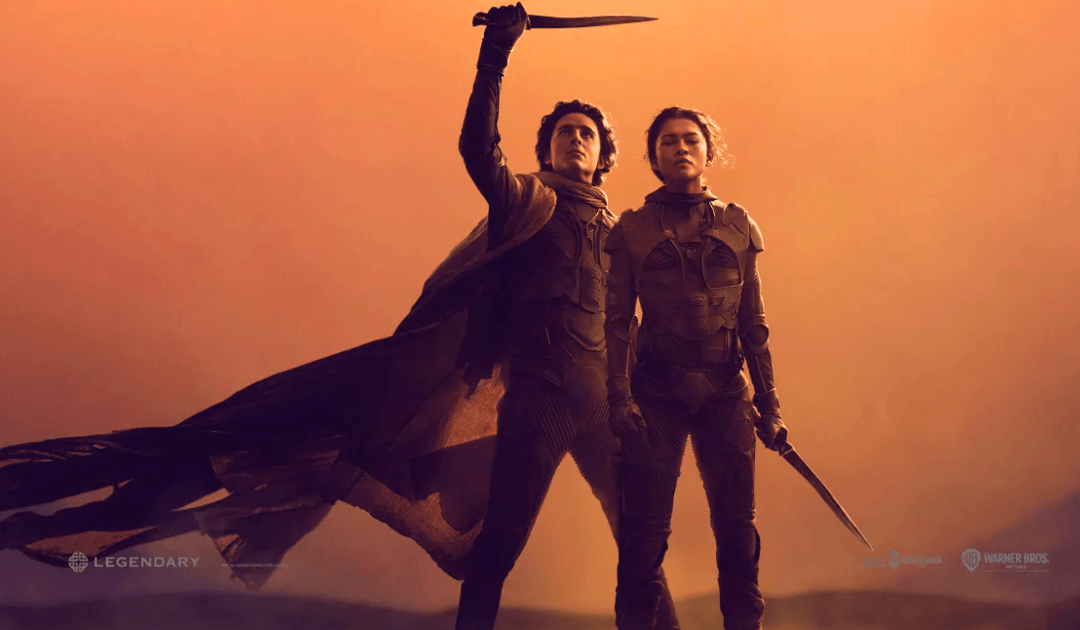

Dune: Part Two

Written and Directed by Denis Villeneuve

Produced by Mary Parent, Cale Boyter, Patrick McCormick, Tanya Lapointe, and Denis Villeneuve

Starring Timothée Chalamet, Zendaya, Rebecca Ferguson, Josh Brolin, Austin Butler, Florence Pugh, Dave Bautista,

Christopher Walken, Léa Seydoux, Souheila Yacoub, Stellan Skarsgård, Charlotte Rampling, and Javier Bardem

Feature Film

(Warner Bros. Pictures, 2024)

Rated PG–13

I grew up in the kind of religious fundamentalism that could redefine most people’s definition of “religious fundamentalism.” I don’t mean I grew up in a cult — no, that would have been too easy. Hippies in search of a drug-induced “trip” that would bring them closer to God while standing outside in empty fields looking for UFOs might have set off some bells in the heads of other, saner folks. No, I grew up surrounded by seemingly normal people with strong work ethics and family values. They had steady jobs (well, most of them); I attended (at first) regular old public school; and we took vacations like everyone else. But that normalcy was a quaint little veneer behind which hid breakfast table conversations that contained matter-of-fact statements like, “The Antichrist will be Catholic, because that good ol’ King James Bible says that he will be ‘cat-like,’ and what are the first three letters of the word ‘Catholic?’ Can’t beat that with a stick”; or “The rule is: unless ‘whitey’ shows the black man how to play the piano, the tuba, the trombone, the banjo, the saxophone, the clarinet, and the trumpet, he stays squatted in front of a hollow log.”1

Paradoxes abounded. Televisions seemed to play without ceasing, but statements like, “The devil lives in that box,” often accompanied anything that wasn’t a pre-1970 western or didn’t star Clint Eastwood.2 Double-standards were the standard, constantly fluctuating to accommodate the next ludicrous religious idea that took the household by storm — like how, practically overnight, all music (but especially country music) became “of the devil,” with the exception of The Beatles.

Look, I have a bit of an ax to grind here, but I should say up front that I am a happy fundamentalist. I maintain strong convictions about the most fundamental components of the Christian faith, as I believe the apostles did and encouraged the members of the church to do (see 2 Thessalonians 2:15). Yet I have come to recognize that specific facets of my upbringing, though largely normal “on the outside,” are curious oddities at best, and tragic lapses of judgment (and common sense) at worst. Which is why watching Dune: Part Two (2024), as the seconds ticked into minutes, and the minutes dissolved into hours, and there were long, panoramic sweeping shots of desert vistas accompanied by shrieking choral arrangements courtesy of Hans Zimmer, I found myself more and more…let’s say perturbed, because anything else would be too strong a word.

Not So Subtle. Dune: Part Two is, ultimately, a film about religious fundamentalism. And subtlety, thy name is not Denis Villeneuve. Most religious critics will pick up on this rather quickly.3 Brett McCracken over at The Gospel Coalition compared Paul Atreides’s story to that of other popular messianic figures to conclude that “Dune Two [sic.] feels like an artifact of a post-Christian age,”4 which should come as a surprise to absolutely no one who has actually read Frank Herbert’s original books.

Herbert himself said, “I had this theory that superheroes were disastrous for humans, that even if you postulated an infallible hero, the things this hero set in motion fell into the hands of fallible mortals.”5 Villeneuve, who directed both Dune: Part Two and its predecessor, said of the story, “It’s not a celebration of a savior. It’s a criticism of the idea of a savior, of someone that will come and tell another population how to be, what to believe. It’s not a condemnation, but a criticism.”6 So, considering that both Dune (2021) and now the sequel are faithful to Herbert’s distinct vision, these films are not so much artifacts of a “post-Christian age” than they are close adaptations of a particularly secular flavor of religious skepticism from around the mid-to-late twentieth century — one that paints with the most basic of colors containing shockingly few hues.

In short, Dune: Part Two sees anything that even remotely resembles religious devotion as being either the manifestation of a chronically oppressed and desperate (that is, “brainwashed”) population, or a mask worn by the puppeteers who pull the strings manipulating said population’s convictions to bring about their own ends. Is Paul Atreides (Timothée Chalamet) a legitimate and long-prophesied messiah figure called Lisan al Gaib? Well, it doesn’t really matter, in the end. The Fremen and, in particular, Stilgar (Javier Bardem), believe that he is, providing Lady Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson) and the other members of the Bene Gesserit order with a religious conviction to amplify, expand, and manipulate toward their own ends.

Religious devotion is here portrayed as fundamentalism — just count the number of times someone refers to the “fundamentalist groups” in the film. It’s like the film would have us believe that said fundamentalists are an extreme element of the Fremen, splinter groups united by their militant devotion to a prophesied messianic figure. This would make more sense. Yet viewers are never really afforded the opportunity to meet just a regular old follower of the Zensunni belief system (the “official” name for the Fremen religion, based on a blending of the beliefs of the Sunni Islamic branch and Zen Buddhist ideas). And, of course, by film’s end, the different Fremen tribes have united under Paul’s banner (literally) to exact revenge against House Harkonnen and the Padishah Emperor, Shaddam IV (Christopher Walken).

In other words, if one were to meet Christians in the way that Paul Atreides meets Fremen in Dune and Dune: Part Two, then every Christian would have a touch of Ruckmanism7 to them — borderline militant in their religious devotion, isolationist, and, yes, a little brainwashed to believe things about their faith without necessarily having a strong faith in and of itself. It is the kind of thing I myself had to be rescued from — but stand today as a testament to the fact that one can, in fact, be rescued from it. Not everyone who adheres to a religious idea automatically becomes radicalized in their beliefs, and “fundamentalist” is not necessarily a “bad word.” Yet Dune: Part Two seems to disagree with that assertion.

Now, maybe it seems like I’m reaching a little too far here. But the whole point of this story, according to the man who made both films, is “a criticism of the idea of a savior.” If that is the case, then the least the film could do is present some balance to the equation. And no, I don’t mean through Chani (Zendaya), who sleeps with Paul and flirts with the messianic ideas but is never quite taken in by the Fremen’s religious fervor. If anything, she seems more “atheistic” in her outlook on religion than anything else.

The Call to Endure. Once again, this film is nowhere near as subtle as it thinks it is. The religious adherents are all fundamentalists (of the worst kind), and the only one who manages to see through the delusion is the one who throws the baby out with the bathwater and walks away from it all. What the film sorely misses is nuance — a Fremen or faction of Fremen who see Paul for who he is, who see the strings being pulled by the Bene Gesserit, who do not feel the need to go to war against the Harkonnen because they understand that there will always be someone in power and that someone will be flawed, who somehow manage to hold their religious convictions firmly in fist without feeling a need to swing it with enough force to injure. In short, Fremen who simply endure the suffering — you know, like Paul pleads with Timothy to do (2 Timothy 4:5), as Peter encourages the Jewish Christians in Diaspora to do (1 Peter 2:20), as Jesus Himself tells His disciples to do, even as He does it Himself (John 16:33).

But that would not gel with the way high and holy Herbert views messianic figures or those who follow them. It simply would not do to represent the average person who relies on their religious convictions to get them through each day, who isn’t some Bible-thumping stick-in-the-mud who believes that Donald Trump is the fourth person of the Trinity (I know, Trump and Herbert are separated by time and space, but the ideas at play can be cross-pollinated).

Watching Dune: Part Two felt a bit like listening to that one “enlightened” friend talk about why they know better than you and everyone else about religion, or reading a Reddit post from an overly-zealous keyboard warrior who has a couple of degrees in some chi-chi sounding field (let’s go with “social-cultural anthropology”), explaining to all the other peons why religion is ultimately detrimental to society as a whole in an argument that basically boils down to, “If you believe in God, you’re stupid and make other people stupid.” But to say it that way sounds — God forbid — offensive to the people they’re offending, so they just say it in a more convoluted and pedantic way using fifteen-dollar words that even someone with a bachelor’s degree has to sound out.

“Now wait,” I hear you say, “is it really that bad?” Yes. It is. Thematically and philosophically. As a film, though? It’s pretty good. Big, bombastic action scenes and jaw-dropping special effects, a rollicking soundtrack by the always-great Hans Zimmer (minus the ever-present screeching choir), and reliable performances from some of the best actors working in Hollywood today. It’s thrilling and emotional in the way epics are emotionally resonant — but it understands exactly what kind of story Herbert set out to tell.8 And, to Villenueve’s credit, he has a huge amount of respect and an intricate understanding of the source material such that he adapts it with an almost religious reverence for what Herbert wrote (ironic, isn’t it?).

Yet I cannot imagine this will be a film that I watch again anytime soon. Dune: Part Two is a bit like someone who never drinks diet soda taking a drink of diet soda — it’s the aftertaste that gets you. And it seems to have that Avatar (2009) quality to it: the kind of film that makes a splash right when it comes out and demands to be seen on the biggest screen possible because it genuinely is breathtaking cinema, but then fades from everyday conversation until advertisements for the next sequel begin to drop because people go back to their normal lives and realize the film is nowhere near as transgressive as it tries to be.

That, however, is through no fault of Villeneuve or the production team. All they are doing is adapting what is on the page in front of them. The problems begin with the source material.

Cole Burgett is a graduate of Dallas Theological Seminary and the Moody Bible Institute. He teaches classes in systematic theology and Bible exposition and writes extensively about theology and popular culture.

NOTES

- The first quote is from a family member. It sounded as stupefyingly ignorant to my thirteen-year-old self as it sounds now. The second quote is from Peter S. Ruckman, Discrimination: The Key to Sanity (Pensacola, FL: Bible Believers Press, 1994), 20. For reference, Ruckman (1921–2016) had what might be called “celebrity status” in at least one of the households of my childhood. He was a kind of twisted genius Independent Fundamental Baptist (IFB), who believed that the King James Version was “advanced revelation.” That is, he believed it to be more inspired than the original autographs. In keeping with my decades-long attempt to separate myself from his inane teachings, I refrain from linking any of his work or teachings here. You can look him up if you so choose. Or you could not and just thank me later.

- To be clear, this is not me taking a shot at westerns — I actually adore the genre more than anyone I’ve ever met and devoured dozens of Louis L’Amour novels in my high school years. I’ve seen every episode of Gunsmoke (1955–1975) and can quote practically every line of Sergio Leone’s Dollars trilogy in my sleep. The western is one of the few good things I was exposed to in my youth.

- A quick Google search of “Dune: Part Two Religious Fundamentalism” brought up articles from U. S. Catholic, The Gospel Coalition, and Christianity Today as the top three results — go figure.

- Brett McCracken, “‘Dune: Part Two’: Cinematic Spectacle, Faith Skeptical,” The Gospel Coalition, March 1, 2024, https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/article/dune-two-spectacle-skeptical/.

- Frank Herbert, Dune: The Banquet Scene Read by the Author Frank Herbert, directed by Ward Botsford (New York: Caedmon, 1977), audio recording.

- Denis Villeneuve, quoted in Eric Eisenberg, “Dune: Denis Villeneuve Responds to Criticisms That the Sci-Fi Epic Is a White Savior Story,” Cinemablend, September 6, 2021, https://www.cinemablend.com/news/2573106/dune-denis-villeneuve-responds-criticisms-sci-fi-epic-white-savior-story.

- “Ruckmanism” is the term used to denote the impassioned beliefs fueled by the teachings of Peter Ruckman. “Ruckmanites” is thus used to describe those who follow his teachings. While they would not classify themselves as a cult — they all claim to follow Jesus and the King James Bible, after all — it is Jesus as Ruckman presents him, and the King James Bible as Ruckman presents it.

- See my review of the first film, Dune (2021), for a brief discussion of the “science fiction epic” as a genre: Cole Burgett, “Dune and the Future of the Science Fiction Epic,” Christian Research Journal, November 10, 2021, https://www.equip.org/articles/dune-and-the-future-of-the-science-fiction-epic/.