This article first appeared in the Effective Evangelism column of the Christian Research Journal, volume29, number4 (2006). For further information or to subscribe to the Christian Research Journal go to: http://www.equip.org

Witnessing to Latter-day Saints (Mormons) can be challenging, since they often use the same words or phrases that Christians use, but pour very different meanings into them. It is helpful to employ creative ways to overcome this “language barrier” so as to present the true meaning of the gospel of Jesus Christ.

One useful approach that I discovered a few years ago is to ask, “Who died for the Book of Mormon?” The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints calls its Book of Mormon “Another Testament of Jesus Christ.” Hebrews9:16–17, however, states, “For where a testament is, there must also of necessity be the death of the testator” (KJV). Mormon authority Bruce McConkie concurs: “In a legal usage, a testator is one who leaves a valid will or testament at his death.”1 If the Book of Mormon is really “Another Testament” in the same sense that divides the Bible into Old and New Testaments, then Latter-day Saints must produce a body to validate it. Again, where there is a testament, the testator must have died; so it is appropriate to ask, “Who died?”2

Why Ask Questions? Asking questions sometimes helps to avoid the typical arguments that Christians and Mormons engage in over certain doctrinal issues. Asking a Mormon questions that lead to the topic, “Who died?” for instance, can create a discussion about biblical covenants and salvation. Such a dialogue provides an opportunity to clarify the gospel message and to raise doubts in the Mormon’s mind about the Book of Mormon. To be successful, however, you must ask the questions as invitations to study Scripture and not as accusations.

Imagine, for example, that a couple of neatly dressed Mormon missionaries arrive at your door one evening and ask if they can come in and talk about God’s plan. Once inside, everyone exchanges introductions and takes a seat around the kitchen table. The missionaries ask, “Have you heard about the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or the Book of Mormon?”

You respond, “Yes, actually, I am intrigued by your book’s subtitle, ‘Another Testament of Jesus Christ.’ I recently read an article about testaments, like the Old and New Testaments of the Bible, and discovered that I had misunderstood what those titles implied. Do you know what a testament is, or what kind of testament the Book of Mormon is? The article said that whenever a testament was mentioned, I especially should ask, ‘Who died?’ It really is interesting. Just take a look at Hebrews9:16–17.” You’re now on your way to a dialogue.

What is a “Testament”? Many Christians and Mormons alike think the titles “Old Testament” and “New Testament” use the word testament in the sense of a testimony someone would give, such as in a court of law. Those titles, however, are derived from the covenants that dominate each portion of the Bible respectively. In fact, as far as the Bible is concerned, a testament is always a covenant. The King James Version, for instance, which Latter-day Saints use exclusively, renders the Hebrew word berit and the Greek word diatheke, both of which mean “covenant,” as “testament.” The New International Version generally translates berit and diatheke as “covenant” or “will,” but never as testimony.3

The notion that testament means “testimony,” therefore, is a misunderstanding. One way to drive this point home is to read Hebrews9:16–17 again, this time using the words testimony and witness rather than testament and testator. The result, “For where a testimony is, there must also of necessity be the death of the witness,” is not what the writer of Hebrews had in mind. Likewise, the titles “Old Testament” and “New Testament” are not referring to testimonies, but rather to the Bible’s two major covenants.4

This is the first point to establish when using the “Who died?” approach: the titles “Old Testament” and “New Testament” refer to covenants.

Vassals or Heirs? Your Mormon visitors respond by saying, “I never really thought about the Old and New Testaments like that before.”

You reply, “Well, I hadn’t either until just recently. What was more surprising for me was that there could be more than one kind of biblical covenant.”

The second point you go on to explain is that biblical covenants come in two basic varieties: Suzerain-Vassal (conditional) or Royal Grant (unconditional). In the biblical world a Suzerain-Vassal covenant regulated “the relationship between a great king [a suzerain] and one of his subject kings [a vassal]. The great king claimed absolute right of sovereignty, demanded total loyalty and service (the vassal must ‘love’ his suzerain) and pledged protection of the subject’s realm and dynasty” based on the condition that the vassal performed whatever service the suzerain demanded.5 A Royal Grant, in contrast, offered benefits unconditionally to a servant or heir.6

The central theme of the Old Testament is God’s covenant with Israel at Mount Sinai, where, after rescuing the Israelites from slavery in Egypt, God promises to protect and bless the people of Israel if and only if they perfectly obey His laws. This covenant, called the Mosaic or Sinaitic Covenant, is what the Old Testament is named after and is a Suzerain-Vassal agreement.7 Note its language: “Now if you obey me fully and keep my covenant, then out of all nations you will be my treasured possession” (Exod.19:5, emphasis added).8

The New Testament gets its name from the covenant that Jesus secured for all humanity, wherein God promises to forgive humanity’s sins (e.g., Jeremiah31:31–37 [although this is an Old Testament passage it describes the new covenant which is manifest in Christ]; 2Cor.3:4–6; Heb.7–8). The language of this covenant is different: “‘The time is coming,’ declares the Lord, ‘when I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel and with the house of Judah. It will not be like the covenant I made with their forefathers….For I will forgive their wickedness and will remember their sins no more’” (Jer.31:31,34). In this Royal Grant agreement God unconditionally agrees to forgive the sins of His subjects or heirs and write His laws on their hearts. They need to do nothing to reap these benefits except believe.

After you have explained that biblical testaments or covenants can be either conditional or unconditional, you ask another question of your Mormon visitors: “If the Book of Mormon is indeed ‘Another Testament’ between God and humanity after the same fashion as the Bible’s Old and New Testaments, then it must be one or the other. So, which kind of covenant is it: does it consider us vassals or heirs?” The determining factor, of course, is whether people need to do anything to earn the benefits offered in the covenant. (You might remind your guests here of the LDS doctrine that requires “obedience to the laws and ordinances of the Gospel” for salvation.9)

Who or What Shed Blood? Most biblical covenants, no matter how great or how small, required blood or death for validation. For example, God’s covenant with Noah in Genesis9 was in response to the “pleasing aroma” of the animal sacrifice in 8:20. In Genesis15:9–15, God has Abram cut up a heifer, a goat, and a ram as a sign of His covenant promise to provide a homeland for Abram’s offspring. Circumcision provided blood for the covenant of Genesis17. Blood was also central in the Mosaic Covenant: “When Moses had proclaimed every commandment of the law to all the people, he took the blood of calves…and sprinkled…both the tabernacle and everything used in its ceremonies. In fact, the law requires that nearly everything be cleansed with blood, and without the shedding of blood there is no forgiveness” (Heb.9:19–22, emphasis added).

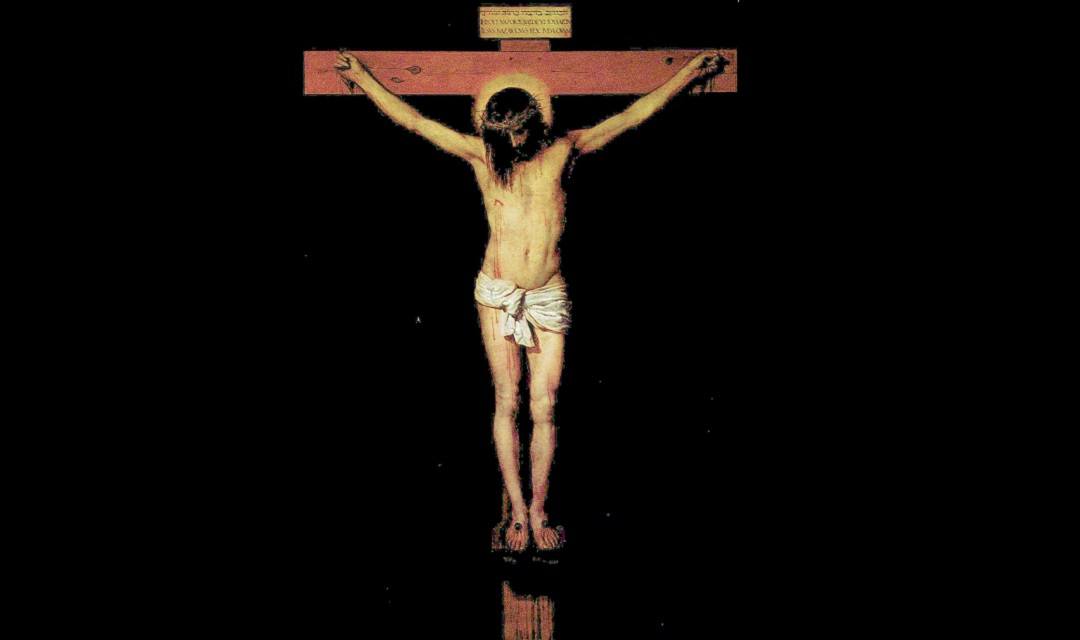

The New Testament or covenant also required blood. According to Hebrews9:1–17 and elsewhere, Jesus Christ’s own blood, not the blood of goats and bulls, was offered so that humanity can have lasting forgiveness. This new covenant is a special kind of Royal Grant. It is a will, which unconditionally provides not only the forgiveness of sins, but the inheritance of eternal life.

This is the third important point to communicate to your Mormon visitors. The Old Testament was validated with the death and blood of animals and the New Testament was validated with the death and blood of Christ; therefore, the Book of Mormon “Testament” also requires validation through the death and blood of someone or something.

You might say to them, “I hope you can see why I was curious about the Book of Mormon’s subtitle, ‘Another Testament of Jesus Christ.’ Who or what died and bled to validate it? If the Mormon testament really is different from the New Testament, does that mean Christ’s death and blood validated two covenants? If so, what does the Mormon testament gain the believer, since forgiveness and eternal life came with the New Testament?”

These questions serve as launching points for further discussion about salvation under the biblical covenants. In the Old Testament, animal blood provided a temporary covering for human sins, but the blood offered year after year could not make the people clean or perfect; in fact, “it is impossible for the blood of bulls and goats to take away sins” (Heb.10:1–4). In the New Testament, Christ offers Himself on our behalf and God promises to put His laws in believers’ hearts and minds and forgive their sins (Heb.10:16–17).

Remember, the ultimate goal of the “Who died?” approach is not to stump Mormons, or even merely to raise doubts in their minds about the Book of Mormon. It is to proclaim the gospel of Christ to them, with love and gentleness.

— Armando Emanuel Roggio, Sr.

NOTES

1. Bruce McConkie, Mormon Doctrine, 2nd ed. (Salt Lake City: BookCraft, 1977), 784–85, s.v. “Testator.”

2. Roger Manwiller (a medical chaplain in Idaho Falls, Idaho) and his mother, Joanna Manwiller, developed the “Who died?” approach sometime after the LDS Church added the subtitle in October 1982. For information about this addition, see “Report of the 152nd Semiannual General Conference of the Church of Jesus Christ: Sermons and Proceedings of October 2–3, 1982, from the Tabernacle on Temple Square,” Ensign, November 1982,1.

3. Edward W. Goodrick and John R. Kohlenberger III, Zondervan NIV Exhaustive Concordance, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1999), s.v. “berit” (p.1382), “diatheke” (p.1540).

4. If a Mormon points out that the LDS general authorities intended “Another Testament” to mean “witness,” not “will,” which probably is true, he or she must then admit that those authorities misunderstood the biblical concept of testament. Refer them to Bruce McConkie’s statement, “The will or testament is the written document wherein the testator provides for the disposition of his property. As used in the general sense, a testament is a covenant.” Mormon Doctrine,784–85.

5. Kenneth Barker, ed., The NIV Study Bible (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1995), 19. Such arrangements existed from ancient times, although the phrase Suzerain-Vassal covenant did not exist until the fifteenth century.

6. Ibid.

7. Stephen L. Harris, Understanding the Bible, 3rd ed. (Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Publishing Company, 1992),13–16.

8. All Bible quotations are from the New International Version unless otherwise noted.

9. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, “The Articles of Faith,” no.3, http://www.lds.org/library/ display/0,4945,106-1-2-1,00.html.