This article was published exclusively online in the Christian Research Journal, Volume 46, number 03 (2023).

When you support the Journal, you join the team and help provide the resources at equip.org that minister to people worldwide. These resources include our ever-growing database of over 2,000 articles, as well as our free Postmodern Realities podcast.

Another way you can support our online articles is by leaving us a tip. A tip is just a small amount, like $3, $5, or $10, which is the cost of a latte, lunch out, or coffee drink. To leave a tip, click here

Summary Critique Book Review

Amy Peeler

Women and the Gender of God

Eerdmans, 2022

“I present this book as an apologia of the unwavering conviction that drives my life,” writes Amy Peeler in her thoughtful and creative work, Women and the Gender of God. The conviction that

the Christian God loves women, a conviction most keenly felt, I should say, not in the library, where I feel God’s pleasure in discovery, not even in the classroom, which I love more than I can articulate, but chiefly when I stand at the altar each week, where I cross the cross emblazoned over my chest as one has been granted the supremely undeserved grace to come in the name of the Lord. Throughout the years in which I have struggled through texts and conversations that whispered that God’s love was less for me because I am female, the Lord I met at the table each week would never allow me to believe the lie.1

Arriving thus, at the end of her argument, I found my own suspicions confirmed, formed in reading the first few lines of her introduction. This writer, I said to myself, has experienced the life-changing truth that God knows and loves her intimately, un-shadowed by the veil of gendered misunderstanding.

This experience is essential for every believer in a time when one’s sex is the defining characteristic of self-knowledge. I know many women, including myself, who discovered the character and shape of God’s knowledge as a staggering revelation. God knows me, a woman, not as a man knows a woman, but as me. There is no lack, for Him, which means He cannot be thought of as a man, but, as the catechism says, having “not a body like men.”

Why the long delay in discovering this essential truth? I was in my early twenties. Rev. Dr. Amy Peeler is a lauded professor of New Testament at Wheaton College, a notable Christian university. Shouldn’t this be the sort of thing a child discovers as part of growing up? Peeler casts it up to the patriarchy, which, she insists, has so damaged women that to proclaim that they are “valued” by God is to say something astonishing.2

The patriarchy, I believe, is a diversion, a tired, limping boogie man. It is the easiest villain, shielding both men and women from experiencing the true life-changing knowledge that their created design is good, and that the order God, as Father, establishes for His Kingdom is not oppressive. Recovering this forgotten and gracious gift would, indeed, benefit both men and women.

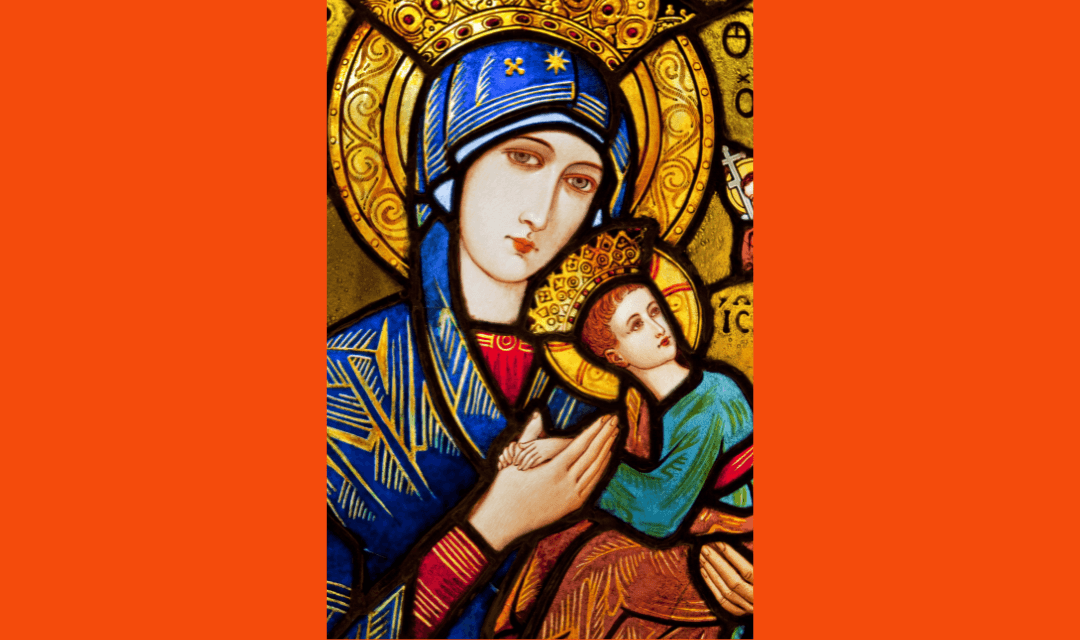

Rather than recovering it, however, Peeler sets out to rescue God from an idea that no one, especially in mainstream evangelicalism today, falls prey to. God, she explains, in case it had not occurred to you, is not male. Moreover, His advent into the world as a man through His mother, Mary, incorporates women into salvific history, elevating them to serve at the Lord’s Table and to preach in the sacred assembly. While God is certainly triune — Peeler affirms naming the relationships in the Godhead of the Father, the Son, and the Spirit3 — the most important thing about Jesus, according to Peeler, is that He was uniquely shaped by the prophetic parenting of His mother. While affirming key biblical typologies like the Bridegroom and the Bride, she insists that there is nothing really masculine about Jesus, nor the Father, and that it might be okay to think of God as divine Parent, or even Mother.4

All these claims, and many others, flow from Peeler’s personal discovery that God values her. Like so many other experientially driven works of this decade, while one is grateful that she affirms the basic tenets of orthodox Christian doctrine, the reader will discover that her biases cause her to miss key logical pieces in her own argument. She is arguing against a case that almost no one makes, and few believe, which makes her conclusions all the more curious, if not absolutely wrong.

The Patriarchy. Peeler contends that many within Christian history have blasphemously5 believed and taught that God is male. The necessary consequence of this wrong belief is that women up to the present day have been grossly mistreated. These “failures,” she writes, “against women proceeded unabated, sometimes malicious and predatory, sometimes subconscious and unintended, practiced by both men and women, on each other and on themselves.” It is for this reason that the “claim that God values women sounds audacious given Christianity’s checkered history and, infuriatingly, its tabloid-worthy present.”6 Peeler makes the ahistorical assertion that Christianity itself “was birthed and cultivated in patriarchal soil, and therefore, it simply got women wrong.”7 This declaration, made so early in the book, makes it difficult to fairly consider her argument. What does Peeler mean by “Christianity” in this instance? Does she mean the writings of the New Testament? Or the era of the church fathers? And what did they, whoever they are, get wrong?

Vagueness and ambiguity plague the work. Imprecision allows Peeler to assemble uncontested doctrines and then draw conclusions unwarranted by the data she presents. For example, in discussing the roles of women in the church, she insists that “If women are not allowed to represent Christ, those Christian communities are utilizing a flattened view of His maleness, one that forgets the mode of His incarnation. This weakened Christology becomes a pathway to the false and damaging male-making of God the Father. The male Savior whose flesh came from the body of a woman provides a radically inclusive embrace of all humanity, a humanity made in the image of God.”8 Thus she sweeps away those communities closest to the view of Mary she espouses — Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox. In neither of those traditions are women “allowed to represent Christ” in the way she means, at the Eucharistic Table. And yet I think it unfair to say that they “utilize a flattened view” of Christ’s “maleness.” These kinds of judgments are imprecise, at best, and slanderous at worst. What does she mean by “maleness”? If Jesus was a man — and Peeler agrees that in virtue of His earthly body He was a man and continues to be so in eternity — then the incarnate Son of God is male (and the very standard of maleness and masculinity).

Lacking for time and space to address every outré conclusion Peeler draws, ceding to other excellent reviewers the larger issues in her work — such as her misunderstanding of Chalcedon,9 her failure to define the terms “masculine” and “feminine,”10 her appeal to Judith Butler11 — I would like to address just two ways her assumption about the inherent sexism of the patriarchy leads her into strange places.12 The first is the idea of consent-based morality, and the second is what I will call a genderless, representational Jesus, one who is devoid of any masculine (or feminine) characteristics that might be recognizable to members of the human race.

Consent-Based Morality. Joining the ranks of current scholars who view the past with suspicion and even contempt, Peeler writes that there is a “deeper, often hidden, and therefore more insidious cause of Christianity’s failure to value women.” It isn’t just that Christians don’t understand or value women, in fact, “Christianity often gets God wrong” (emphasis added). In spite of what you may hear pastors and theologians say to the contrary, “the assumptions and actions of interpreters from the past to the present disclose an underlying belief that God is male.”13 To counter these assumptions, and to lay the groundwork for all people, both men and women, to “image” God, Peeler turns to the Bible, which she affirms is the source and ground of what we know about God. Immediately, however, she runs into a problem. Many decades of deconstructionism have eroded trust in the biblical witness. Peeler feels called upon to defend the narrative from corrosive feminist assumptions, in this case, what we today would call consent-based morality.

In this way of thinking, any claim a man places on a woman, especially in the realm of sexuality, existentially threatens her unless she is first able to render “consent.” In the aftermath of the Sexual Revolution, as women have tried to recover the power they had before the advent of the birth control pill, the last bulwark against the bad behavior of men is consent. As long as both people consent, neither one can complain, however uncomfortable either felt. In the post-Me-Too world, many women have discovered consent to be inadequate, to put it mildly, as a currency for affairs of the heart.14

When modern people approach the Bible, having been shaped by the idea of consent, the moment when the Angel Gabriel comes to Mary to announce the Incarnation, the question they first ask is, “Did Mary consent?” Did God take advantage of her? Was she able to say yes in a meaningful way? Peeler devotes a whole chapter to what the church, through the ages, has called Mary’s “Fiat” or “Let it be.” Two elements are important for Peeler, though they lead her to sketch a Mary Sue version of Mary.15 In the first place, Mary comes into the encounter with Gabriel from a position of strength rather than weakness; and in the second place, she draws attention to herself rather than God.

“The powerful God,” writes Peeler, “approaches Mary with honor and blessing and waits for her response. She, the young circumspect female, with grit and self-respect, accepts. The exchange then is not between one strong and one weak, one forceful male and one forced female, but between one God and one human woman, who both act for her honor from the place of strength.”16 She explains that Gabriel’s announcement that she “will” conceive, bear a son, and name him Jesus constitutes a “danger” but that Luke moves through that treacherous territory to create “space for her willing agency.”17 The moment of safety comes in the form of Gabriel’s explanation. “Coercion,” she writes, “need not explain itself, but Gabriel does. Gabriel does so by showing that God has been at work already in Mary’s family.”18 Mary’s yes, then, comes in the form of the Magnificat, in which, Peeler asserts, Mary “calls attention to herself. From the beginning, the account has involved her: her story, her family, her body, and so she identifies herself as the focal point. Look at me” (emphasis in original).19

Apologetically noting that Mary’s use of the word “slave” (Luke 1:38, 48) has a “problematic nature,” Peeler nevertheless faithfully draws the obvious parallels between this text and Philippians 2:7, the “central assertion of Pauline Christology,”20 illustrated most fully in John when Jesus “washes the feet of his disciples (John 13).”21 Finally, she insists that the Lukan narrative has Mary “permit” the “impact” of an “action initiated by God.”22 “In both her statements,” Peeler writes, “’Behold the handmaid of the Lord!’ and ‘Let it be unto me according to your word,’ Luke presents the delicate balance of both self-respect and humility. Look at me! I am a slave of the Lord. Let the good and hard word happen to me. Luke has portrayed Mary as a complex character offering a self-involved response” (emphasis in original).23 Before addressing this peculiar sketch of Mary, let’s consider the Son she brings forth into the world.

A Genderless Jesus. Having rescued Mary from divine rape, Peeler turns to rehabilitate the questionable character of God who would dare to offend modern sensibilities by incarnating Himself as an actual man. She does this by centering the humanity of Jesus in the femininity of Mary — though she never defines the terms masculine or feminine:

Mary is not simply the place for the God-man, the vessel through which he passes, a thing. If the Son of God has flesh, and Christianity has banked its entire system on the affirmation that he does, that flesh is drawn from her. In the Christian imaginary, as centered on the incarnation, that is no small thing. The human body is granted even greater value through this doctrine. God has not only created but entered into human flesh. The distinction between divine and human, spirit and flesh, is breached and forever transformed. Consequently, the female contribution of flesh, cultivated by the spirit of God, is not the unimportant part but the very contribution where God chose to reveal, and ultimately revealed, the divine identity.24

Throughout Peeler’s narration, one cannot help but notice that Mary, rather than God the Father, or even the Son, is the most important character in the story of salvation. Her body, her flesh, her will, her mothering of Jesus are what the biblical writers mean for us to notice.

Furthermore, we may observe that Peeler rejects Jesus’ masculinity in favor of His empowered mother. Although the Son of God is a divine person who has taken upon Himself a fully human nature — He is truly divine and truly human — His humanity, per se, according to Peeler is not sufficient to bring about the salvation of both men and women:

If Jesus were not birthed as a male, he would not include male bodies in his recapitulation. If he were not birthed and conceived from a woman alone, he would not include female bodies in his recapitulation. I seek not to erode but to emphasize his maleness, the way it came about, to show its unique particularity specifically as it regards male and female. No woman can be excluded from imagining God because his male body came only from a woman.”25

Articulating the mode of the Incarnation in this way strikes me as theologically tortured. It privileges the question of representation — whether or not you can find yourself represented in the content you are consuming — over the biblical narrative. God, being God, has the power to save. To illustrate His character and nature, He did it by involving human creatures — Mary particularly as the counterpoint of Eve. The Son was incarnated as a man, the second Adam, as the fulfillment of the type God traces through the history of Israel as the bridegroom who rescues a bride. To dismiss Jesus’ “maleness” is to reject the gendered texture of that very typology. God presents Himself as the bridegroom of Israel, and Jesus the husband of the church.

Finally, in leaning on the terms “male” and “maleness” without fleshing out what they mean, Peeler claims that Jesus was “unlike every other male, for his embodied maleness broadens to include the female body from which he came. The particular Savior’s body came from a particular Jewish woman.”26 Peeler doesn’t have any Scriptural support for this assertion, which, in fact, contradicts texts that point out that Jesus was like “his brothers” in every way (Hebrews 2:17). Being a literal man, His masculinity had to be like that of every man, except for sin. Peeler then insists that “this Jesus as the bridegroom grants no support for God the Father as the exclusively male-imaged husband.”27 On what basis does God then call Himself the husband of Israel? Only because of His relationship to the Son. “If God is the bridegroom of the people of God,” she explains, “it is not because God is more similar to men than women. It is because God the Father is one with the Son. The bridegroom image is defined by the Son. Christ’s bridegroom and maleness and therefore Yahweh’s role as a husband is determined by the Son’s particular incarnation as a male” (emphasis in original).28 The word “similar” carries the weight of her contention, and yet it is so imprecise a term. In the way that Mary carries the burden of Jesus’ humanity, Jesus now carries the burden of God’s typological character as bridegroom and husband. Which is to say a true thing. And yet, at the same time, Peeler’s emphasis is on the wrong syllable. God uses the metaphor of Bride and Bridegroom precisely because they are so closely and intimately bound to the gendered human experience. They are instantly recognizable at a gut and heart level before the mind has had time to explain them away.

Saving God from Himself. In his short, seminal work, Gender, Ivan Illich makes the case that, in the aftermath of the Industrial Revolution (though the cracks were showing long before), something essential about human nature was lost.29 He calls it “Vernacular Gender.” It was the assumption in every place through history about what it “meant” to be either a man or a woman. Though the particulars varied, the differentiation between male and female was woven through the whole. I grew up in a culture still fastened together by vernacular gender. To be a woman meant to be embedded in a complicated network of relationships bound by material and spiritual obligations. On the surface, one might say that a woman is the person who collects the firewood to heat the bath water for the man, but that was only the outward sign of the deeper, hidden threads that tie men and women together in their common humanity.

Illich says that vernacular gender was replaced by “Economic Sex.” Economic sex represents the commodification of everything and every relationship. It spelled, for women particularly, the loss of purpose and meaning — technology untethered spiritual and metaphysical meaning from biology.

Peeler’s work illustrates rather beautifully how devastating it has been for women to lose themselves in the post-industrial age. The poetry and music of God’s exchanging Adam and Eve’s ruin for their salvation, reversing the curse through Jesus and Mary, bringing humanity once more into communion with Himself are not sufficient unless they answer the corrosive doctrines of this moment. In the sublime weakness of a creature being the vessel of the Creator, Mary cannot simply offer herself in humility and wonder, foreshadowing the complete emptying of the self that her Son would do at the cross. She must become a girl boss. Jesus, the second Adam, cannot come in power and, by the poignant and perfect sacrifice of Himself for the one He loves, slay His greatest enemy. He must, rather, live in the shadow of His mighty mother and His helpless Father.

And all this so that Peeler and other women can ascend the steps to the Lord’s Table as His ministers. “The proof,” writes Peeler, “of an appropriate incarnational view of God appears, it seems to me, in the strictures for church leadership. Just as men are encouraged to imagine themselves as members of the bride, women should be freely encouraged to imagine themselves as members of Christ the bridegroom. As men can represent the church, so women can represent Christ. Thomas Hopko argues that for some feminist interpreters ‘the maleness of Jesus Christ has nothing to do with the ordained Christian ministry.’”30 In one sense, of course, she is right. Christ, our brother and friend makes even women into His own image through the mighty work of the Spirit. And, as Lewis says, even men should contemplate their strange participation as members of the Bride. And yet, God made us men and women in order that we might know Him as we are, and He know us according to His good pleasure. It is only in recovering these lost blessings that happy communion may be found. Rewriting the script to accommodate the paltry ruin of consent and representation doesn’t end up making God any more palatable than before. Perhaps it is best to take Him as He is, and let Him speak for Himself. —Anne Kennedy

Anne Kennedy, MDiv, is the author of Nailed It: 365 Readings for Angry or Worn-Out People, rev. ed. (Square Halo Books, 2020). She blogs about current events and theological trends at Standfirminfaith.com and on her Substack, Demotivations with Anne.

NOTES

- Amy Peeler, Women and the Gender of God (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2022), 190.

- Peeler, Women and the Gender of God, 1.

- Peeler, Women and the Gender of God, 17.

- Peeler, Women and the Gender of God, 17.

- Peeler, Women and the Gender of God, 106.

- Peeler, Women and the Gender of God, 1.

- Peeler, Women and the Gender of God, 1.

- Peeler, Women and the Gender of God, 147.

- Marcus Johnson, “Women and the Gender of God,” Themelios, Vol. 48, Issue I, https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/themelios/review/women-and-the-gender-of-god/.

- Denny Burk, “Should We Call God Mother?” The Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood, January 17, 2023, https://cbmw.org/2023/01/17/should-we-call-god-mother/.

- John C. Clark, “Getting God Right?” Touchstone, https://www.touchstonemag.com/archives/article.php?id=36-03-040-b.

- For a helpful look at how the church has understood God as Father, see Michael Bauman, “The Fatherhood of God: Christian Feminists versus Christ and the Creed,” Christian Research Journal, 23, 2 (2000): 28–33, https://www.equip.org/articles/god-as-father/.

- Peeler, Women and the Gender of God, 2.

- I recommend the work of Louise Perry and Mary Harrington for those who wish to think more deeply about this subject.

- For a brief definition and etymology of the term, see “Mary Sue,” Fictional Characters Dictionary, https://www.dictionary.com/e/fictional-characters/mary-sue/.

- Peeler, Women and the Gender of God, 66.

- Peeler, Women and the Gender of God, 66.

- Peeler, Women and the Gender of God, 75.

- Peeler, Women and the Gender of God, 77.

- Peeler, Women and the Gender of God, 79.

- Peeler, Women and the Gender of God, 79.

- Peeler, Women and the Gender of God, 83.

- Peeler, Women and the Gender of God, 83.

- Peeler, Women and the Gender of God, 149.

- Peeler, Women and the Gender of God, 145.

- Peeler, Women and the Gender of God, 144.

- Peeler, Women and the Gender of God, 144.

- Peeler, Women and the Gender of God, 144.

- Ivan Illich, Gender (London: Marion Boyars, 1983).

- Peeler, Women and the Gender of God, 144–45.