This article first appeared in the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL, volume 38, number 06 (2015). The full text of this article in PDF format can be obtained by clicking here. For further information or to subscribe to the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL go to: http://www.equip.org/christian-research-journal/

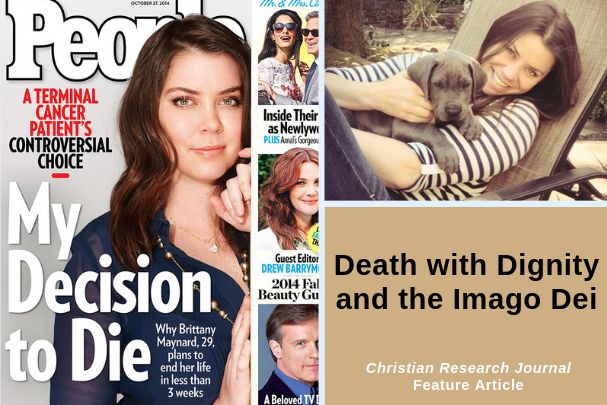

Brittany Maynard, at the age of twenty-nine, was diagnosed with terminal brain cancer. Unable to receive lethal prescriptions in her home state of California, she moved to Oregon for her final days because it is one of a few states that currently allow physician assisted suicide (PAS).1 She shared her story via a recording advocating for the organization Compassion and Choices and an expansion of laws permitting PAS. It is hard to imagine anyone not being moved by her desire to avoid suffering and die peacefully in the presence of her loved ones. Lawmakers in almost half the states prepared to pursue PAS laws in the wake of this emotional outpouring for Maynard and people like her, and Governor Jerry Brown signed California’s PAS bill into law on September 11, 2015. She ingested her lethal prescription on November 1, 2014, in the presence of her family, and, consistent with Oregon law, her official cause of death is listed as a brain tumor.

Maynard’s story breaks our hearts, but the nature of the claims being made regarding human rights can’t be ignored because we are rightfully moved. She advocated for laws grounded in a claimed right to control her death with medical assistance. California State Senator Bill Monning, while proposing California Senate Bill 128, or the End of Life Option Act, didn’t simply express his wish that no individual have to endure a painful death—a position that all reasonable people hold. He claimed that PAS is a fundamental human right.2 These are moral statements about the nature of our lives, our community, and our duties to the terminally ill. Arguments from misery are powerful, but the understandable emotions of the moment cannot dictate the ethics of our future.

Human beings are the image bearers of God, the imago Dei, and our duties and obligations to one another and our community are best evaluated through that lens. Reflections on how the imago Dei establishes intrinsic human value and determining exactly what people are arguing for in a proposed “right to die” are vital. Particular rights claims need to be distinguished and identified in order to evaluate their merits properly. A right to refuse medical treatment is different from a right to die, and the acceptance of the former in no way obligates codifying the latter. There is an additional danger that embracing PAS and a right to die leads many emotionally and physically vulnerable members of our community to perceive a duty to die. It would be better to focus on serving the dying in our community with a renewed effort to protect their dignity by caring for them in a manner that honors their intrinsic value.

THE IMAGE OF GOD AND HUMAN VALUE

We intuitively understand that there are actions that are wrong when performed, and most acknowledge that these duties and obligations represent real objective moral values that we discover rather than create and that universally apply to human relationships. These intuitions about the nature of human relations are best explained through the recognition of human beings as the image bearers of God. God made us in His image, His likeness (Gen. 1:26–27), and endowed us, as J. P. Moreland says, with “reason, self-determination, moral action, personality, and relational formation.”3 This nature makes it wrong to shed innocent human blood (Gen. 9:6). Our personhood is grounded in a personal God that bestows worth on us that we can never acquire by virtue of our own merits.4

Our value is intrinsic, held by virtue of what we are, and we experience that through the recognition of universal injustices regardless of differing societies and cultures. This only makes sense if there is something about every human being that is universally shared irrespective of our race, ethnicity, or culture—a common nature. Thomas Jefferson articulated this idea in the Declaration of Independence, and the founding fathers of the United States of America justified their rebellion by an appeal to rights that exist prior to human government. Legitimate governments don’t invent these rights: they recognize them and exist to protect them. In the same way, claims of a fundamental right to die like those offered by Maynard and Senator Monning must appeal to something about our nature that anchors that right and renders all societal restrictions of that right as unjust.

Harvard scholar Mary Ann Glendon wrote that Americans mistakenly tend to express personal desires in the language of personal rights.5 But once any one member of society claims a fundamental right to die, rather than a desire to die, then the rest of society has obligations and duties to secure that right. Doctors must prescribe medicine to facilitate death, the legislative process must craft laws to protect that right, our judicial and criminal justice system must act to enforce such laws, and so on. Rights claims, unlike desire claims, unavoidably draw obligations from the surrounding community.

THE RIGHT TO REFUSE TREATMENT

A principle of autonomy, a freedom to determine what happens to me as an individual, explains a perceived right to refuse medical treatments. As life-support technology advances, it is reasonable to affirm a right as individuals to say enough is enough and cease exhaustive medical efforts to keep us alive. Those who hold to a restrictive view on the practice of PAS and euthanasia are sometimes mistakenly understood to advocate some form of vitalism, the idea that we are morally obligated to preserve all life in all cases. On the contrary, a mentally competent adult should be allowed to refuse invasive medical procedures that offer little hope of impacting the outcome. When our best medical efforts fruitlessly rage against the natural dying process, we should not demand that our loved ones live every possible second that medical science can force on them.

Autonomy is reasonably limited, though. Selling ourselves into chattel slavery is immoral. It is normally understood as wrong for doctors to mutilate healthy bodies on the request of a patient no matter how much he or she may desire for the doctor to do so. Cassandra, a seventeen-year-old minor in Connecticut, was recently forced to continue chemotherapy for Hodgkins Lymphoma against her will after she refused treatment with her mother’s consent to explore alternative holistic treatment plans. The state assumed the role of responsible guardian abdicated by Cassandra’s mother when she allowed her daughter to reject a treatment plan that, when begun early, promises a 90–95 percent survival rate in favor of a course of action that would only allow the lymphoma time to advance. Autonomy is important, but obviously not all choices in regard to our bodies are morally appropriate.

FROM RIGHT TO REFUSE TO RIGHT TO DIE

A right to refuse treatment doesn’t obligate us to embrace a right to die. The former recognizes a personal freedom to end treatment while the latter intentionally brings about death. Proponents believe that PAS is the most compassionate option to those facing terminal illnesses with extreme suffering. Barbara Coombs Lee, the president of Compassion and Choices and the architect of the Oregon PAS law, argues that the law in Oregon and other states is intended to prevent the abuses by people and organizations with broader conceptions of euthanasia rights such as Jack Kevorkian and the Hemlock Society. Lethal prescriptions are strictly limited to terminal cases where death is imminent, a great deal of suffering is highly likely, and the patient is free from any underlying psychiatric conditions. Proponents of such laws reject the characterization of these cases as suicide since terminally ill patients don’t desire death per se but rather to choose the time and conditions of their death. They desire some “dominion” over their body as disease and illness conspire to leave them powerless. Just like the right to refuse medicine, they argue, this is the reasonable exercise of autonomy.6

John Keown of Cambridge points out that this is not solely an argument from autonomy but also from beneficence; the doctor acts to the benefit of the patient by ending suffering.7 This distinction is critical in evaluating right-to-die claims. The desire to be free to make an autonomous choice to avoid suffering is understandable, but personal choice is not the deciding factor when laws are crafted in the United States. Two doctors must determine that your medical case meets the extremely narrow parameters they consider necessary for it to be in your best interest to terminate life and thus avoid a life not worth living. Is it the proper role of a physician to make such judgments? How do they determine when there has been enough suffering, or death is sufficiently imminent, to justify prescribing death as the best course of action? As G. K. Chesterton once wrote, a doctor has “the right to administer the queerest and most recondite pill which he may think is a cure for all the menaces of death. He has not the right to administer death as the cure for all human ills.”8

Arthur Caplan, head of the Division of Medical Ethics at NYU, supports the U.S. laws, though he admits to being troubled that the Netherlands and Belgium moved down a slippery slope to nonvoluntary euthanasia and euthanizing children. He believes that Oregon and Washington appear untouched by similar abuses,9 a point the Canadian Supreme Court used as a justification for approving the legality of physician-assisted suicide in Canada. Critics respond that the only reason that we know of the abuses in the Netherlands and Belgium is because of multiple in-depth studies in those nations focusing on determining what doctors are doing and their intentions in doing so. No such studies have been done regarding Oregon and Washington.10 Caplan’s evidence for success in those states is that the electorate seems happy with the laws, but without additional data to support it, this reasoning amounts to ethics by polling.

Everyone agrees that our medical system is woefully deficient in its efforts to deal with death compassionately. The disagreement centers on how we move toward a solution. Ira Byock, a leading physician in the hospice movement, argues that we have not seen additional moves toward a more compassionate approach where these laws have been enacted. PAS is offered as the solution and not a step toward some- thing better. Recognizing the terminally ill as intrinsically valuable requires that we attend to their needs in a compassionate manner through expansions of hospice care and awareness of advances in palliative care. It does not require us to participate actively in requests to die, and a right to die unavoidably makes that decision a societal act.

CREATING A DUTY TO DIE

Finally, rights and responsibilities always go together, and embracing a right to die leads to an implied or tacitly understood duty to die. Terminally ill patients often fear the impact their last days will have on their families as much or more than they fear physical suffering. Affirming that end of life challenges are a legitimate reason for hastening death can confirm a terminal patient’s worst fears of being a burden.

In his book Dying Well, Byock shares the story of how he begged his dying father to allow him to care for him in those last days. He assured his father that it would be his honor to attend to those needs his dad saw as personal indignities.11 This is our shared challenge. We must foster a culture that assures every member that they are fully human, valued, and cherished even at their most vulnerable moments. Otherwise, we risk cultivating a community that reinforces that it would be better to die quickly because our last days are every bit as horrible as we imagine. Is there any wonder why advocates for the disabled fear setting a standard that those who do not live up to certain ideals will be determined to be living lives not worth living?12 Marilyn Golden of the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund said, “Assisted suicide automatically becomes the cheapest (treatment) option….They (patients) are being steered toward hastening their deaths.”13

Building a culture that honors the intrinsic value of all life and protects the most vulnerable among us might be more difficult than simply accommodating the heartbreaking cries for relief, but we must be careful not to allow misplaced empathy to cloud our judgment. The terminally ill are still the image bearers of God. As the medical power to extend life increases, so should our obligations to craft a humane, merciful, and charitable society toward our sick and dying.

Jay Watts is vice president of Life Training Institute (LT). He speaks at universities, high schools, and churches across the United States and participates in numerous radio and television interviews on the subject of the value of human life.

NOTES

- Malak Monir, “Half the States Look at Right-to-Die Legislation,” USA Today, April 16, 2015, http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2015/04/15/death-with-laws-25-states/25735597/.

- Ibid.

- J. P. Moreland, The Recalcitrant Imago Dei: Human Persons and the Failure of Naturalism (London: SCM Press, 2009), 4.

- Nicholas Wolterstorff, Justice (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008), 352.

- Mary Ann Glendon, Rights Talk: The Impoverishment of Political Discourse (New York: The Free Press, 1991).

- “The Latest Debate over ‘Aid in Dying,’” The Diane Rehm Show, February 17, 2015, http://thedianerehmshow.org/shows/2015-02-17/the_latest_in_the_debate_over_aid_in_dying.

- John Keown, “A Right to Euthanasia?” Public Discourse, October 16, 2014, http://www.thepublicdiscourse.com/2014/10/13936/.

- G. K. Chesterton, Eugenics and Other Evils (New York: Cassell and Company, 1922), 42.

- “The Latest Debate over ‘Aid in Dying.’”

- John Keown, “A Right to Voluntary Euthanasia? Confusion in Canada in Carter,” Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics, and Public Policy 28, 1 (May 1, 2014): 29–31.

- Ira Byock, Dying Well (New York: Riverhead Books, 1997), 22.

- Monir, “Half the States Look at Right-to-Die Legislation.”

- Ibid.