This article first appeared in CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL, volume 33, number 01 (2010). The full text of this article in PDF format can be obtained by clicking here. For further information or to subscribe to the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL go to: http://www.equip.org/christian-research-journal/

SYNOPSIS

Much like the man he was named for, Martin Luther King, Jr., was a reformer and a revolutionary. A minister and civil rights leader whose legacy will reverberate through history long after we’re gone, King’s philosophy and theology were influenced by the black church’s “social gospel,” which sought to alleviate societal problems based on Christian ethics, white Protestant liberalism, and the philosophy of men such as Mahatma Gandhi. King undergirded the civil rights movement, at least in the beginning, with Christian principles of forgiveness, faith, love, and brotherhood. He resented racial segregation and the disrespectful treatment that resulted from it, but he tried to counter the treatment with hope for racial equality.

King is best known for his powerful speeches. His nonviolent approach to resisting oppression was commendable and worthy of emulation by Christians, but what he believed about the faith causes concern. Some of King’s private writings seem to indicate that he rejected biblical literalism. He may have remained privately skeptical until his death. Regardless, King’s life serves as a prominent example of someone who appealed to Christian brotherhood to bring about racial justice.

Refusing to return violence for violence, King sought to eradicate segregation through peaceful protests in the face of opposition. He challenged the church and the role it played in racial segregation and called on Christians to confront injustice. For that, King is worthy of esteem, but Christians should be aware of King’s beliefs, most importantly his doubts about the resurrection of Christ.

In 1934, the Rev. Michael King, Sr., changed his name to Martin Luther King in honor of Martin Luther, the German Protestant reformer. Luther took on the powerful Roman Catholic Church. He criticized the papacy and such practices as indulgences and the “good works” salvation plan, and translated the Bible to the common language so the masses could read and study God’s Word for themselves, rather than have it filtered through the church. Only by faith alone, through God’s grace alone, was the sinner saved. This message spread throughout western Europe and eventually the world.

Luther was a revolutionary who took on a powerful system, and his spiritual passion ushered in the Protestant Reformation, changing the course of western civilization.

Martin Luther King, Jr., was a reformer and revolutionary of a different sort. King stood at the forefront of the civil rights movement, a secular reformation with Christian underpinnings, and changed the course of American history.

Every January 15th, America pays homage to the man whose bold oratory and use of civil disobedience (nonviolent resistance) roused the country from its racial slumber and hastened the dismantling of government racial segregation. One of the most turbulent periods in our history, the Civil Rights era is most associated with King.

Four decades after his death, his legacy reverberates. The legacy isn’t without controversy, however. Given recent revelations about his personal life, plagiarism,1 and his beliefs about Christianity, some may conclude he’s no longer worthy of such reverence. Others believe that despite his moral failings and questionable theology, King has earned a place of respect for challenging a system that codified racial separation and branded black Americans as inferior. We should ask, therefore, “Are King’s ideas relevant to contemporary Christian apologetics?”

KING’S LIFE AND WORK

King was born into a middle-class family in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1929. This son, grandson, and great-grandson of ministers grew up in the church but began doubting his faith once he realized the cold reality of racial discrimination.2 King writes of his resentment toward the injustice of racial segregation and the harsh treatment that sprang from it. One can feel his bitterness as he recounts scenes from his formative years in which he, his family, and his friends were subjected to condescending and disrespectful treatment. He tried to reconcile his faith with this treatment, particularly after a white friend’s father told him not to play with King anymore. “My parents would always tell me that I should not hate the white man, but that it was my duty as a Christian to love him. The question arose in my mind: How could I love a race of people who hated me and who had been responsible for breaking me up with one of my best childhood friends? This was a great question in my mind for a number of years.”3

At fifteen, King entered Morehouse College. He first learned about nonviolent resistance after reading Henry David Thoreau’s “On Civil Disobedience,” in which the author wrote about his refusal to pay taxes to protest “a war that would spread slavery’s territory into Mexico.”4 King ruminated on the notion of rebelling against segregation rather than accepting it.

After graduating from Morehouse with a bachelor of arts in sociology, King entered Crozer Theological Seminary. He went on to receive a B.A. in divinity from Crozer and a Ph.D. from Boston University. At age twenty-five and newly married, King and his wife, the former Coretta Scott, headed south, and he became a minister at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama. In 1955, the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) selected King to oversee the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the unofficial start of the civil rights movement. The city’s black citizens protested Montgomery’s racial segregation policy on buses by avoiding the buses, sharing rides, taking taxis, and walking. Vigilantes bombed King’s and the Rev. Ralph Abernathy’s houses almost two months into the boycott.5 The MIA filed suit in federal court. Pressure mounted, and on June 4, 1956, the court ruled the city’s segregated bus policy unconstitutional. On November 13, 1956, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the court’s ruling.

The boycott, which lasted 381 days, thrust King into the national spotlight. Emboldened by this victory, King helped found the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in 1957 and served as its president until his death in 1968. Through the SCLC King and Abernathy began to harness the power of the black church as the political center for social action. On May 15, 1957, King gave the first of his famous Washington speeches titled, “Give Us the Ballot.”

Later that year, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1957, the first legislation of its kind since Reconstruction. In 1958, King’s first book, Stride toward Freedom, was published. Ironically, King was stabbed by a black woman at a book signing. After almost dying, King viewed this experience as a sort of case study. “I became convinced that if the movement held to the spirit of nonviolence, our struggle and example would challenge and help redeem not only America but the world.”6

Influenced by Mahatma Gandhi’s civil disobedience campaign that ended British rule in India, King applied the techniques to his protest campaign. He encouraged participants to assemble peacefully and demand their constitutional rights through appeals to justice and brotherhood, even in the face of violence.

King traveled to India in 1959 to study Gandhi’s philosophy. He recalled that he and his traveling companions were treated as brothers, and he felt bonded to the Indians “by the common cause of minority and colonial peoples… struggling to throw off racism and imperialism.”7 As his own words attest, King was influenced by his faith and Gandhi’s techniques, writing that “Christ furnished the spirit and motivation while Gandhi furnished the method.”8

The civil rights movement continued in earnest as “sit-in” demonstrations began in 1960. In 1961, whites and blacks from the North traveled south in “freedom rides”; in 1962, King met with President John F. Kennedy; in 1963, King delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech; and in 1964, King became the youngest person to ever win the Nobel Peace Prize. Over the course of the campaign, King was arrested thirty times.9

In late March of 1968, King went to Memphis, Tennessee, to lead a march of sanitation workers protesting low wages and poor working conditions. He was fatally shot April 4 on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel.

Shortly after King’s death, supporters began a campaign to commemorate his birth with a federal holiday. Congress man John Conyers introduced a bill in 1968; opposing lawmakers stalled it. In 1983, President Ronald Reagan signed the holiday into law. Twenty-seven states and Washington, D.C., observed the holiday, and in 2000, all fifty states observed it.10

INFLUENCES AND APPLICATION

King graduated from Crozer Theological Seminary, a school that had an “unorthodox reputation and liberal theological leanings.”11 His philosophical and theological beliefs were a combination of the black church tradition (in which “black theology” reigned) and white Protestant liberalism. His sermons and speeches reflect these influences.

Liberal theology is linked to the cultural shift toward Progressivism in politics and religion in the late nineteenth century,12 a movement focused on so-called social justice. Generally, liberal theology holds that the Bible’s truth claims aren’t absolute. They must be based on reason and experience rather than an appeal to an external authority. In other words, Scripture is authoritative concerning religious matters, but it’s not authoritative concerning claims about facts. Conservative theology, on the other hand, holds that the Bible is the inspired, inerrant, and infallible word of God, and its authority extends to all areas of life.

Black theology, which emerged from liberal theology, takes into account the black subcultural experience and attempts to apply Christian principles to social problems that affect blacks. Some Christians object to the idea of a black theology and believe it shouldn’t exist, though Reformed black authors such as Anthony J. Carter and Thabiti M. Anyabwile would take exception. Carter says the majority culture believes its theological approach is culture-free, but it isn’t. “Theology in a cultural context…has become normative.” Carter gives examples of theology distinguished by culture (German Lutheran, Scottish Reformed, etc.).13

Western Christianity, dominated by white males, “has had scant if any direct answers to the evils of racism and the detrimental effects of institutionalized discrimination.”14 Consequently, liberal theology, which tended to address black oppression in a way conservative churches didn’t, heavily influenced the black church. For better or for worse, “we need a sound, biblical black theological perspective because an unsound, unbiblical black theological perspective is the alternative.”15

The black church wasn’t always associated with liberal theology. Anyabwile, who traced the development of black theology through slave narratives, slave songs, and popular writings past and present, concluded that before emancipation, black Christians tended to be more orthodox in their beliefs than they are today.16 Early black Christians were concerned about justice and freedom, but their mission was to spread the gospel as well as practice social justice activism. The black church veered from the path: “Over time, especially following emancipation from slavery through the Civil Rights era, the theological basis for the church’s activist character was gradually lost and replaced with a secular foundation.”17

Advocating for social justice isn’t unbiblical; it becomes so when the advocacy is man-centered instead of Christ-centered. King acknowledged this danger in his writings. While at Crozer, he read social philosopher Walter Rauschenbusch’s book, Christianity and the Social Crisis, which gave his own social justice ideas a “theological basis,” but he diverged from Rauschenbusch’s “superficial optimism concerning man’s nature.”18 King believed Rauschenbusch had become “perilously close to identifying the Kingdom of God with a particular social and economic system—a tendency which should never befall the Church.”19

King was raised in a “strict fundamentalist tradition” and found that studying liberal theology roused him from his “dogmatic slumber.”20 A liberal view of the Bible gave him more “intellectual satisfaction”21 than the conservative view, but as he further examined these liberal ideas, he saw faults in them as well. He wrote, “Liberalism’s superficial optimism concerning human nature caused it to overlook the fact that reason is darkened by sin…Liberalism failed to see that reason by itself is little more than an instrument to justify man’s defensive ways of thinking.”22

King maintained his liberal theological beliefs while at Boston University, but he “became much more sympathetic towards the neo-orthodox position,” which he saw as “a necessary corrective for a liberalism that had become all too shallow and that too easily capitulated to modern culture.”23 He adopted the philosophy of personalism, “the clue to the meaning of ultimate reality is found in personality.”24 From a Christian perspective, it’s the idea that God, and not society or even ourselves, establishes our worth.25 At the time of the writing of his autobiography, King held to this philosophical position.26

With a confluence of ideas from thinkers such as Plato, Aristotle, John Locke, Karl Marx, Nietzsche, Gandhi, Reinhold Niebuhr, and theologically liberal professors, King emerged from Boston University with what he called a “positive social philosophy.”27

King had no qualms about preaching politics from the pulpit. After the Montgomery Bus Boycott, he preached on an “imaginary” letter from the apostle Paul to American Christians.28 While Paul’s letters to the churches reflected spiritual matters, King’s sermon-letter was a mixture of the spiritual and the political, noting that capitalism is a system in which America has “been able to do wonders,” but we faced the danger of misusing capitalism, which can lead to “tragic exploitation.”29 King criticized the class system and implored Christians to work “within the framework of democracy to bring about a better distribution of wealth.”30

King criticized communism and Roman Catholicism, praised the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision, which ruled the doctrine “separate but equal” unconstitutional, and urged congregants not to allow the struggle for justice to turn them bitter or seek payback for injustices. “Let him know that the festering sore of segregation debilitates the white man as well as the Negro. With this attitude you will be able to keep your struggle on high Christian standards.”31

King continued to incorporate biblical themes into his public speeches. In one of his early speeches, he hoped to prompt the federal government to begin integrating schools in the aftermath of Brown. In the 1957 speech “Give Us the Ballot,” delivered at the Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom rally on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., King said: “I realize that it will cause restless nights sometimes. It might cause losing a job; it will cause suffering and sacrifice. It might even cause physical death for some. But if physical death is the price that some must pay to free their children from a permanent life of psychological death, then nothing can be more Christian.”32

King was arrested on April 12, 1963, in Birmingham for defying a court order against mass demonstrations. King’s long and eloquent “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” a reply to a brief rebuke, was perhaps his most memorable piece of writing. Responding to white clergy decrying “outsiders” protesting in the streets of their city and contending that social injustices should be fought in courts, King compared himself to biblical prophets. He said he carried the “gospel of freedom” to all men, and it required “direct action” as opposed to waiting. “We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.”33

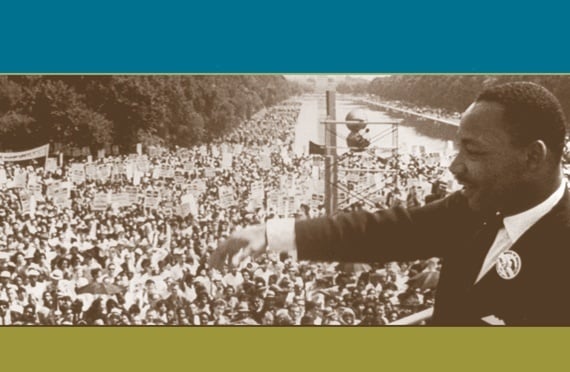

As the civil rights movement progressed, King realized total victory would not come quickly. In his famous speech, “I Have a Dream,” delivered on August 28, 1963, at the Lincoln Memorial, King invoked the Founders’ promise. A century after emancipation, “the Negro is still not free…still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination.”34 Without overtly appealing to white Christians, King said it was time to extend justice to all God’s children and warned there would be no peace until justice was done.

Until the end of his life, he continued to connect social justice and biblical themes in speeches and sermons, and to challenge the church to live up to biblical ideals.

WERE KING’S BELIEFS BIBLICAL?

The black church’s influence on King’s message is evident from his writings and in the substance and delivery of his speeches. He also was influenced by liberal theologians at Crozer and Boston. King’s orthopraxy—correct behavior in religious matters—at least in public, left a legacy all Christians may emulate. What about his orthodoxy, his actual beliefs? Are they compatible with biblical Christianity?

Black pastor Jerry L. Buckner wrote that orthodoxy in the black church in general isn’t strong for several reasons. The most relevant reason in this context is that pastors in black churches “lack a formal orthodox theological education,” and many who are formally educated attended schools that espouse liberal theology.35 Buckner does note that theologically conservative seminaries didn’t admit black applicants whereas liberal seminaries “aggressively recruited” blacks.

Biblical Christianity, in its simplest terms, is belief in doctrines of the faith as revealed in the Bible. For instance, the Bible is the divinely inspired word of God, and it teaches, among other things, that sin is an offense against God, man is fallen, having inherited sin from Adam, sin is rebellion against God, and victory over sin is found in Jesus Christ. I will focus on the central tenet—the bodily resurrection of Christ.

King was a precocious child to the point of verbalizing his doubts about the bodily resurrection of Christ at age thirteen.36 Recently discovered papers King wrote while at Crozer reveal that he still questioned the authenticity of such doctrines as the resurrection.37

In 1985, Coretta Scott King asked Stanford professor Clayborne Carson to become the head of The King Papers Project, tasked to publish fourteen volumes of King’s papers to preserve his work.38 The papers’ dates range from 1948 to 1963. Around 1996, Mrs. King gave Carson a box with papers that affirmed King’s doubts about whether the Bible was literally true: “King didn’t believe the story of Jonah being swallowed by a whale was true, for example, or that John the Baptist actually met Jesus, according to texts detailed in the King papers book. King once referred to the Bible as ‘mythological’ and also doubted whether Jesus was born to a virgin, Carson said.”39

While at Crozer, King argued that the Apostles’ Creed probably was influenced by Greek thought, and “in the minds of many sincere Christians this creed has planted a seed of confusion which has grown to an oak of doubt. They see this creed as incompatible with all scientific knowledge, and so they have proceeded to reject its content.”40

In “What Experiences of Christians Living in the Early Christian Century Led to the Christian Doctrines of the Divine Sonship of Jesus, the Virgin Birth, and the Bodily Resurrection,” written in 1949 when King was twenty, he wrote that external evidence for the authenticity of the Resurrection is “found wanting.” He implied that the bodily resurrection was a mythological story early Christians spread to explain “the faith that he could never die” and to symbolize their experiences with Christ.41

Without the bodily resurrection of Christ there is no hope of salvation, and we’re still in our sins (1 Cor. 15:17). Based on these early papers, one could make the case King did not believe in basic tenets of the faith. One might also argue that his papers merely were theoretical exercises in which he stated and supported a thesis. Should we take into account King’s relative youth at the time? If these were his beliefs, did he ever repudiate them? Perhaps examining the entirety of his work will lead Christians to a definitive answer.

KING’S LEGACY AND OUR APOLOGETICS

Is King’s legacy still relevant to Christians today? Absolutely. Whether or not King’s beliefs later in life adhered to biblical Christianity, he infused the civil rights movement with Christian principles. The era brought about great and much-needed change.

When interacting with King’s legacy, the apologist must separate the wheat from the chaff. For example, King argued in favor of civil disobedience under the just/unjust law theory in “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” a topic that Christians on both sides of the issue have debated for centuries and will continue to debate. King wrote that “one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws,”42 and contended that a just law is a man-made law in harmony with the moral law, or God’s law. An unjust law is not. One of King’s examples of an unjust law is one in which the majority compels the minority to obey, but the majority doesn’t bind itself to obey.

Apologists attempting to make the case for or against disobeying unjust laws and/or arguing whether a law is unjust may look to King as an example of a man who did both.

That King was influenced by Gandhi’s philosophy and other non-Christian ideas should give us pause. It is important that Christians avoid becoming entangled in interfaith dialogue to the point where we fail to address theological distinctives on which we cannot compromise. In the same matter, it should give us pause that King doubted the resurrection of Christ, the very foundation of the Christian faith, and other tenets of the faith.

As the church grapples with racial issues today, King’s life may serve as an example of someone who challenged the church to live up to biblical ideals and invoked Christ in the name of racial justice. We must keep in mind the context in which King developed his views.

At times King doubted his faith, which many Christians do, and his personal shortcomings confirmed he indeed was a fallen man in need of a Savior, as we all are. King’s legacy continues to influence secular and religious arenas, and his method of protesting racial segregation garnered both praise and condemnation. His legacy endures, and the apologist should be prepared to interact with it.

La Shawn Barber is a freelance writer whose work has appeared in such publications as Christianity Today, Today’s Christian Woman, the Washington Post, and the Washington Examiner. Visit her blog at lashawnbarber.com.

NOTES

- Clayborne Carson, “Editing Martin Luther King, Jr.: Political and Scholarly Issues,” in Palimpsest: Editorial Theory in the Humanities, ed. George Bornstein and Ralph G. Williams (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1993), 305–16; available at http:// mlk kpp01.stanford.edu/index.php/home/pages?page=http://mlk-kpp01.stanford.edu/ kingweb/additional_resources/articles/palimp.htm.

- Martin Luther King, Jr., The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr., ed. Clayborne Carson (New York: Warner Books, 1998), 7.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 14.

- Ken Hare, “The Story of the Montgomery Bus Boycott”; available at http://www.montgomeryboycott.com/article_overview.htm.

- King, 119.

- Ibid., 128.

- Ibid., 67.

- The King Center, “Biography”; available at http://www.thekingcenter.org/DrMLKingJr/.

- Francis Romero, “A Brief History of Martin Luther King Jr. Day,” Time, January 19, 2009; available at http://www.time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,1872501,00.html.

- The Martin Luther King, Jr., Encyclopedia; available at http://mlk-kpp01.stanford.edu/ index.php/encyclopedia/encyclopedia/enc_crozer_theological_seminary/.

- Gary J. Dorrien, The Making of American Liberal Theology: Idealism, Realism, and Modernity (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2003), 1.

- Anthony J. Carter, On Being Black and Reformed: A New Perspective on the African-American Experience (Phillipsburg, NJ: P and R Publishing, 2003), 5–6.

- Ibid., 6.

- Ibid., 3.

- Thabiti Anyabwile, The Decline of African American Theology: From Biblical Faith to Cultural Captivity (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2007).

- Ibid., 17–18.

- King, 18.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 24.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 25.

- Ibid., 31.

- Ibid.

- Carl Anderson, A Civilization of Love: What Every Catholic Can Do to Transform the World (New York: Harper One, 2008), 39.

- King, 31–32.

- Ibid., 32.

- Clayborne Carson and Peter Holloran, eds., A Knock at Midnight: Inspiration from the Great Sermons of Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. (New York: Warner Books, 1998); citing from http://mlk-kpp01.stanford.edu/index.php/encyclopedia/documentsentry/ doc_pauls_letter_to_american_christians.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Carson and Holloran; citing from http://www.stanford.edu/group/King/papers/vol4/570517.004-Give_Us_the_Ballot.htm.

- King, 188–204.

- Ibid; available at http://mlk-kpp01.stanford.edu/kingweb/publications/speeches/ address_at_march_on_washington.pdf (July 17, 2001).

- Jerry L. Buckner, “Is Orthodoxy Strong in the Black Church?” Christian Research Journal 27, 4 (2004); available at http://www.equip.org/articles/is-orthodoxy-strong-in-the-black-church-.

- King, 6.

- The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr.; available at http://mlk-kpp01.stanford.edu/index.php/ kingpapers/article/volume_i_13_september_to_23_november_19491/.

- The King Papers Project; available at http://mlk-kpp01.stanford.edu/index.php/kingpapers/ article/what_is_the_king_papers_project/.

- Matthai Chakko Kuruvila, “Writings Show King as Liberal Christian, Rejecting Literalism,” San Francisco Chronicle; available at http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?file=/c/a/2007/ 01/15/MNGHJNIR631.DTL.

- The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr., vol. 1; available at http://mlk-kpp01.stanford.edu/ index.php/kingpapers/article/volume_i_13_september_to_23_november_19491/.

- Ibid.

- King, 188–204.