This article first appeared in the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL, volume 13, number 03 (1991). The full text of this article in PDF format can be obtained by clicking here. For further information or to subscribe to the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL go to: http://www.equip.org/christian-research-journal/

In the first installment of this two-part series, I outlined the stark contrasts between the gnostic Jesus and “the Word become flesh.” These respective views of Jesus are lodged within mutually exclusive world views concerning claims about God, the universe, humanity, and salvation. But our next line of inquiry is to be historical. Do we have a clue as to what Jesus, the Man from Nazareth, actually did and said as a player in space-time history? Should such gnostic documents as the Gospel of Thomas capture our attention as a reliable report of the mind of Jesus, or does the Son of Man of the biblical Gospels speak with the authentic voice? Or must we remain in utter agnosticism about the historical Jesus?

Unless we are content to chronicle a cacophony of conflicting views of Jesus based on pure speculation or passionate whimsy, historical investigation is non-negotiable. Christianity has always been a historical religion and any serious challenge to its legitimacy must attend to that fact. Its central claims are rooted in events, not just ideas; in people, not just principles; in revelation, not speculation; in incarnation, not abstraction. Renowned historian Herbert Butterfield speaks of Christianity as a religion in which “certain historical events are held to be part of the religion itself” and are “considered to…represent the divine breaking into history.”1

Historical accuracy was certainly no incidental item to Luke in the writing of his Gospel: “Many have undertaken to draw up an account of the things that have been fulfilled among us, just as they were handed down to us by those who from the first were eyewitnesses and servants of the word. Therefore, since I myself have carefully investigated everything from the beginning, it seemed good also to me to write an orderly account for you, most excellent Theophilus, so that you may know the certainty of the things you have been taught” (Luke 1:1-4, NIV). The text affirms that Luke was after nothing less than historical certainty, presented in orderly fashion and based on firsthand testimony.

If Christianity centers on Jesus, the Christ, the promised Messiah who inaugurates the kingdom of God with power, the objective facticity of this Jesus is preeminent. Likewise, if purportedly historical documents, like the gospels of Nag Hammadi, challenge the biblical understanding of Jesus, they too must be brought before historical scrutiny. Part Two of this series will therefore inspect the historical standing of the Gnostic writings in terms of their historical integrity, authenticity, and veracity.

LOST BOOKS OF THE BIBLE?

Although much excitement has been generated by the Nag Hammadi discoveries, not a little misunderstanding has been mixed with the enthusiasm. The overriding assumption of many is that the treatises unearthed in upper Egypt contained “lost books of the Bible” — of historical stature equal to or greater than the New Testament books. Much of this has been fueled by the titles of some of the documents themselves, particularly the so-called “Gnostic gospels”: the Gospel of Thomas, Gospel of Philip, Gospel of Mary, Gospel of the Egyptians, and the Gospel of Truth. The connotation of a “gospel” is that it presents the life of Jesus as a teacher, preacher, and healer — similar in style, if not content, to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John.

Yet, a reading of these “gospels” reveals an entirely different genre of material. For example, the introduction to the Gospel of Truth in The Nag Hammadi Library reads, “Despite its title, this work is not the sort found in the New Testament, since it does not offer a continuous narration of the deeds, teachings, passion, and resurrection of Jesus.”2 The introduction to the Gospel of Philip in the same volume says that although it has some similarities to a New Testament Gospel, it “is not a gospel like one of the New Testament gospels. . . . [The] few sayings and stories about Jesus…are not set in any kind of narrative framework like one of the New Testament gospels.”3 Biblical scholar Joseph A. Fitzmyer criticized the title of Pagels’s The Gnostic Gospels because it insinuates that the heart of the book concerns lost gospels that have come to light when in fact the majority of Pagels’s references are from early church fathers’ sources or nongospel material.4

In terms of scholarly and popular attention, the “superstar” of the Nag Hammadi collection is the Gospel of Thomas. Yet, Thomas also falls outside the genre of the New Testament Gospels despite the fact that many of its 114 sayings are directly or indirectly related to Matthew, Mark, and Luke. Thomas has almost no narration and its structure consists of discrete sayings. Unlike the canonical Gospels, which provide a social context and narrative for Jesus’ words, Thomas is more like various beads almost haphazardly strung on a necklace. This in itself makes proper interpretation difficult. F. F. Bruce observes that “the sayings of Jesus are best to be understood in the light of the historical circumstances in which they were spoken. Only when we have understood them thus can we safely endeavor to recognize the permanent truth which they convey. When they are detached from their original historical setting and arranged in an anthology, their interpretation is more precarious.”5

Without undue appeal to the subjective, it can be safely said that the Gnostic material on Jesus has a decidedly different “feel” than the biblical Gospels. There, Jesus’ teaching emerges naturally from the overall contour of His life. In the Gnostic materials Jesus seems, in many cases, more of a lecturer on metaphysics than a Jewish prophet. In the Letter of Peter to Philip, the apostles ask the resurrected Jesus, “Lord, we would like to know the deficiency of the aeons and of their pleroma.”6 Such philosophical abstractions were never on the lips of the disciples — the fishermen, tax collectors, and zealots — of the biblical accounts. Jesus then discourses on the precosmic fall of “the mother” who acted in opposition to “the Father” and so produced ailing aeons.7

Whatever is made of the historical “feel” of these documents, their actual status as historical records should be brought into closer scrutiny to assess their factual reliability.

THE RELIABILITY OF THE GNOSTIC DOCUMENTS

Historicity is related to trustworthiness. If a document is historically reliable, it is trustworthy as objectively true; there is good reason to believe that what it affirms essentially fits what is the case. It is faithful to fact. Historical reliability can be divided into three basic categories: integrity, authenticity, and veracity.

Integrity concerns the preservation of the writing through history. Do we have reason to believe the text as it now reads is essentially the same as when it was first written? Or has substantial corruption taken place through distortion, additions, or subtractions? The New Testament has been preserved in thousands of diverse and ancient manuscripts which enable us to reconstruct the original documents with a high degree of certainty. But what of Nag Hammadi?

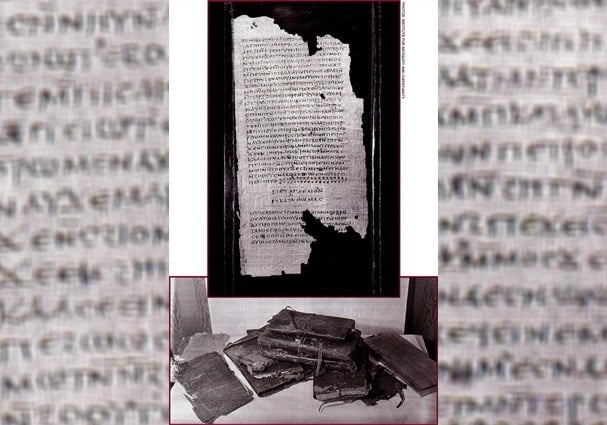

Before the discovery at Nag Hammadi, Gnostic documents not inferred from references in the church fathers were few and far between. Since 1945, however, there are many primary documents. Scholars date the extant manuscripts from A.D. 350-400. The original writing of the various documents, of course, took place sometime before A.D. 350-400, but not, according to most scholars, before the second century.

The actual condition of the Nag Hammadi manuscripts varies considerably. James Robinson, editor of The Nag Hammadi Library, notes that “there is the physical deterioration of the books themselves, which began no doubt before they were buried around 400 C.E. [then] advanced steadily while they remained buried, and unfortunately was not completely halted in the period between their discovery in 1945 and their final conservation thirty years later.”8

Reading through The Nag Hammadi Library, one often finds notations such as ellipses, parentheses, and brackets, indicating spotty marks in the texts. Often the translator has to venture tentative reconstructions of the writings because of textual damage. The situation may be likened to putting together a jigsaw puzzle with numerous pieces missing; one is forced to recreate the pieces by using whatever context is available. Robinson adds that “when only a few letters are missing, they can be often filled in adequately, but larger holes must simply remain a blank.”9

Concerning translation, Robinson relates that “the texts were translated one by one from Greek to Coptic, and not always by translators capable of grasping the profundity or sublimity of what they sought to translate.”10 Robinson notes, however, that most of the texts are adequately translated, and that when there is more than one version of a particular text, the better translation is clearly discernible. Nevertheless, he is “led to wonder about the bulk of the texts that exist only in a single version,”11 because these texts cannot be compared with other translations for accuracy.

Robinson comments further on the integrity of the texts: “There is the same kind of hazard in the transmission of the texts by a series of scribes who copied them, generation after generation, from increasingly corrupt copies, first in Greek and then in Coptic. The number of unintentional errors is hard to estimate, since such a thing as a clean control copy does not exist; nor does one have, as in the case of the Bible, a quantity of manuscripts of the same text that tend to correct each other when compared (emphasis added).”12

Authenticity concerns the authorship of a given writing. Do we know who the author was? Or must we deal with an anonymous one? A writing is considered authentic if it can be shown to have been written by its stated or implied author. There is solid evidence that the New Testament Gospels were written by their namesakes: Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. But what of Nag Hammadi?

The Letter of Peter to Philip is dated at the end of the second century or even into the third. This rules out a literal letter from the apostle to Philip. The genre of this text is known as pseudepigrapha — writings falsely ascribed to noteworthy individuals to lend credibility to the material. Although interesting in explaining the development of Gnostic thought and its relationship to biblical writings, this letter shouldn’t be overtaxed as delivering reliable history of the events it purports to record.

There are few if any cases of known authorship with the Nag Hammadi and other Gnostic texts. Scholars speculate as to authorship, but do not take pseudepigraphic literature as authentically apostolic. Even the Gospel of Thomas, probably the document closest in time to the New Testament events, is virtually never considered to be written by the apostle Thomas himself.13 The marks of authenticity in this material are, then, spotty at best.

Veracity concerns the truthfulness of the author of the text. Was the author adequately in a position to relate what is reported, in terms of both chronological closeness to the events and observational savvy? Did he or she have sufficient credentials to relay historical truth?

Some, in their enthusiasm over Nag Hammadi, have lassoed texts into the historical corral that date several hundred years after the life of Jesus. For instance, in a review of the movie The Last Temptation of Christ, Michael Grosso speaks of hints of Jesus’ sexual life “right at the start of the Christian tradition.” He then quotes from the Gospel of Philip to the effect that Jesus often kissed Mary Magdalene on the mouth.14 The problem is that the text is quite far from “the start of the Christian tradition,” being written, according to one scholar, “perhaps as late as the second half of the third century.”15

Craig Blomberg states that “most of the Nag Hammadi documents, predominantly Gnostic in nature, make no pretense of overlapping with the gospel traditions of Jesus’ earthly life.”16 He observes that “a number claim to record conversations of the resurrected Jesus with various disciples, but this setting is usually little more than an artificial framework for imparting Gnostic doctrine.”17

What, then, of the veracity of the documents? We do not know who wrote most of them and their historical veracity concerning Jesus seems slim. Yet some scholars advance a few candidates as providing historically reliable facts concerning Jesus.

In the case of the Gospel of Truth, some scholars see Valentinus as the author, or at least as authoring an earlier version.18 Yet Valentinus dates into the second century (d. A.D. 175) and was thus not a contemporary of Jesus. Attridge and MacRae date the document between A.D. 140 and 180.19 Layton recognizes that “the work is a sermon and has nothing to do with the Christian genre properly called ‘gospel.'”20

The text differs from many in Nag Hammadi because of its recurring references to New Testament passages. Beatley Layton notes that “it paraphrases, and so interprets, some thirty to sixty scriptural passages almost all from the New Testament books.”21 He goes on to note that Valentinus shaped these allusions to fit his own Gnostic theology.22 In discussing the use of the synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke) in the Gospel of Truth, C. M. Tuckett concludes that “there is no evidence for the use of sources other than the canonical gospels for synoptic material.”23 This would mean that the Gospel of Truth gives no independent historical insight about Jesus, but rather reinterprets previous material.

The Gospel of Philip is thick with Gnostic theology and contains several references to Jesus. However, it does not claim to be a revelation from Jesus: it is more of a Gnostic manual of theology.24 According to Tuckett’s analysis, all the references to Gospel material seem to stem from Matthew and not from any other canonical Gospel or other source independent of Matthew. Andrew Hembold has also pointed out that both the Gospel of Truth and the Gospel of Philip show signs of “mimicking” the New Testament; they both “know and recognize the greater part of the New Testament as authoritative.”25 This would make them derivative, not original, documents.

Tuckett has also argued that the Gospel of Mary and the Book of Thomas the Contender are dependent on synoptic materials, and that “there is virtually no evidence for the use of pre-synoptic sources by these writers. These texts are all ‘post-synoptic,’ not only with regard to their dates, but also with regard to the form of the synoptic tradition they presuppose.”26 In other words, these writings are simply drawing on preexistent Gospel material and rearranging it to conform to their Gnostic world view. They do not contribute historically authentic, new material.

The Apocryphon of James claims to be a secret revelation of the risen Jesus to James His brother. It is less obviously Gnostic than some Nag Hammadi texts and contains some more orthodox-sounding phrases such as, “Verily I say unto you none will be saved unless they believe in my cross.”27 It also affirms the unorthodox, such as when Jesus says, “Become better than I; make yourselves like the son of the Holy Spirit.”28 While one scholar dates this text sometime before A.D. 150,29 Blomberg believes it gives indications of being “at least in part later than and dependent upon the canonical gospels.”30 Its esotericism certainly puts it at odds with the canonical Gospels, which are better attested historically.

THOMAS ON TRIAL

The Nag Hammadi text that has provoked the most historical scrutiny is the Gospel of Thomas. Because of its reputation as the lost “fifth Gospel” and its frequently esoteric and mystical cast, it is frequently quoted in New Age circles. A recent book by Robert Winterhalter is entitled, The Fifth Gospel: A Verse-by-Verse New Age Commentary on the Gospel of Thomas. He claims Thomas knows “the Christ both as the Self, and the foundation of individual life.”31 Some sayings in Thomas do seem to teach this. But is this what the historical Jesus taught?

The scholarly literature on Thomas is vast and controversial. Nevertheless, a few important considerations arise in assessing its veracity as history.

Because it is more of an anthology of mostly unrelated sayings than an ongoing story about Jesus’ words and deeds, Thomas is outside the genre of “Gospel” in the New Testament. Yet, some of the 114 sayings closely parallel or roughly resemble statements in the Synoptics, either by adding to them, deleting from them, combining several references into one, or by changing the sense of a saying entirely.

This explanation uses the Synoptics as a reference point for comparison. But is it likely that Thomas is independent of these sources and gives authentic although “unorthodox” material about Jesus? To answer this, we must consider a diverse range of factors.

There certainly are sayings that harmonize with biblical material, and direct or indirect relationships can be found to all four canonical Gospels. In this sense, Thomas contains both orthodox and unorthodox material, if we use orthodox to mean the material in the extant New Testament. For instance, the Trinity and unforgivable sin are referred to in the context of blasphemy: “Jesus said, ‘Whoever blasphemes against the father will be forgiven, and whoever blasphemes against the son will be forgiven, but whoever blasphemes against the holy spirit will not be forgiven either on earth or in heaven.'”32

In another saying Jesus speaks of the “evil man” who “brings forth evil things from his evil storehouse, which is in his heart, and says evil things33 (see Luke 6:43-46). This can be read to harmonize with the New Testament Gospels’ emphasis on human sin, not just ignorance of the divine spark within.

Although it is not directly related to a canonical Gospel text, the following statement seems to state the biblical theme of the urgency of finding Jesus while one can: “Jesus said, ‘Take heed of the living one while you are alive, lest you die and seek to see him and be unable to do so'” (compare John 7:34; 13:33).34

At the same time we find texts of a clearly Gnostic slant, as noted earlier. How can we account for this?

The original writing of Thomas has been dated variously between A.D. 50 and 150 or even later, with most scholars opting for a second century date.35 Of course, an earlier date would lend more credibility to it, although its lack of narrative framework still makes it more difficult to understand than the canonical Gospels. While some argue that Thomas uses historical sources independent of those used by the New Testament, this is not a uniformly held view, and arguments are easily found which marshall evidence for Thomas’s dependence (either partial or total) on the canonical Gospels.36

Blomberg claims that “where Thomas parallels the four gospels it is unlikely that any of the distinctive elements in Thomas predate the canonical versions.”37 When Thomas gives a parable found in the four Gospels and adds details not found there, “they can almost always be explained as conscious, Gnostic redaction [editorial adaptation].”38

James Dunn elaborates on this theme by comparing Thomas with what is believed to be an earlier and partial version of the document found in Oxyrhynchus, Egypt, near the turn of the century.39 He notes that the Oxyrhynchus “papyri date from the end of the second or the first half of the third century, while the Gospel of Thomas…was probably written no earlier than the fourth century.”40

Dunn then compares similar statements from Matthew, the Oxyrhynchus papyri, and the Nag Hammadi text version of Thomas:

Matthew 7:7-8 and 11:28 — “…Seek and you will find;…he who seeks finds…Come to me…and I will give you rest.” Pap. Ox. 654.5-9 — (Jesus says:) ‘Let him who see(ks) not cease (seeking until) he finds; and when he find (he will) be astonished, and having (astoun)ded, he will reign; an(d reigning), he will (re)st’ (Clement of Alexandria also knows the saying in this form.)

Gospel of Thomas 2 — ‘Jesus said: He who seeks should not stop seeking until he finds; and when he finds, he will be bewildered (beside himself); and when he is bewildered he will marvel, and will reign over the All.’41

Dunn notes that the term “the All” (which the Gospel of Thomas adds to the earlier document) is “a regular Gnostic concept,” and that “as the above comparisons suggest, the most obvious explanation is that it was one of the last elements to be added to the saying.”42 Dunn further comments that the Nag Hammadi version of Thomas shows a definite “gnostic colouring” and gives no evidence of “the thesis of a form of Gnostic Christianity already existing in the first century.” He continues: “Rather it confirms the counter thesis that the Gnostic element in Gnostic Christianity is a second century syncretistic outgrowth on the stock of the earlier Christianity. What we can see clearly in the case of this one saying is probably representative of the lengthy process of development and elaboration which resulted in the form of the Gospel of Thomas found at Nag Hammadi.”43

Other authorities substantiate the notion that whatever authentic material Thomas may convey concerning Jesus, the text shows signs of Gnostic tampering. Marvin W. Meyer judges that Thomas “shows the hand of a gnosticizing editor.”44 Winterhalter, who reveres Thomas enough to write a devotional guide on it, nevertheless says of it that “some sayings are spurious or greatly altered, but this is the work of a later Egyptian editor.”45 He thinks, though, that the wheat can be successfully separated from the chaff. Robert M. Grant has noted that “the religious realities which the Church proclaimed were ultimately perverted by the Gospel of Thomas. For this reason Thomas, along with other documents which purported to contain secret sayings of Jesus, was rejected by the Church.”46

Here we find ourselves agreeing with the early Christian defenders of the faith who maintained that Gnosticism in the church was a corruption of original truth and not an independently legitimate source of information on Jesus or the rest of reality. Fitzmyer drives this home in criticizing Pagels’s view that the Gnostics have an equal claim on Christian authenticity: “Throughout the book [Pagels] gives the unwary reader the impression that the difference between ‘orthodox Christians’ and ‘gnostic Christians’ was one related to the ‘origins of Christianity’. Time and time again, she is blind to the fact that she is ignoring a good century of Christian existence in which those ‘gnostic Christians’ were simply not around.”47

In this connection it is also telling that outside of the Gospel of Thomas, which doesn’t overtly mention the Resurrection, other Gnostic documents claiming to impart new information about Jesus do so through spiritual, post-resurrection dialogues — often in the form of visions — which are not subject to the same historical rigor as claims made about the earthly life of Jesus. This leads Dunn to comment that “Christian Gnosticism usually attributed its secret [and unorthodox] teaching of Jesus to discourses delivered by him, so they maintained, in a lengthy ministry after his resurrection (as in Thomas the Contender and Pistis Sophia). The Gospel of Thomas is unusual therefore in attempting to use the Jesus-tradition as the vehicle for its teaching. . . . Perhaps Gnosticism abandoned the Gospel of Thomas format because it was to some extent subject to check and rebuttal from Jesus-tradition preserved elsewhere.”48

Dunn thinks that the more thoroughly the Gnostics challenged the already established orthodox accounts of Jesus’ earthly life, the less credible they became; but with post-resurrection accounts, no checks were forthcoming. They were claiming additional information vouchsafed only to the elite. He concludes that Gnosticism “was able to present its message in a sustained way as the teaching of Jesus only by separating the risen Christ from the earthly Jesus and by abandoning the attempts to show a continuity between the Jesus of the Jesus-tradition and the heavenly Christ of their faith.”49

What is seen by some as a Gnostic challenge to historic, orthodox views of the life, teaching, and work of Jesus was actually in many cases a retreat from historical considerations entirely. Only so could the Gnostic documents attempt to establish their credibility.

GNOSTIC UNDERDOGS?

Although Pagels and others have provoked sympathy, if not enthusiasm, for the Gnostics as the underdogs who just happened to lose out to orthodoxy, the Gnostics’ historical credentials concerning Jesus are less than compelling. It may be romantic to “root for the underdog,” but the Gnostic underdogs show every sign of being heretical hangers-on who tried to harness Christian language for conceptions antithetical to early Christian teaching.

Many sympathetic with Gnosticism make much of the notion that the Gnostic writings were suppressed by the early Christian church. But this assertion does not, in itself, provide support one way or the other for the truth or falsity of Gnostic doctrine. If truth is not a matter of majority vote, neither is it a matter of minority dissent. It may be true, as Pagels says, that “the winners write history,” but that doesn’t necessarily make them bad or dishonest historians. If so, we should hunt down Nazi historians to give us the real picture of Hitler’s Germany and relegate all opposing views to that of dogmatic apologists who just happened to be on the winning side.

In Against Heresies, Irenaeus went to great lengths to present the theologies of the various Gnostic schools in order to refute them biblically and logically. If suppression had been his concern, the book never would have been written as it was. Further, to argue cogently against the Gnostics, Irenaeus and the other anti-Gnostic apologists would presumably have had to be diligent to correctly represent their foes in order to avoid ridicule for misunderstanding them. Patrick Henry highlights this in reference to Nag Hammadi: “While the Nag Hammadi materials have made some corrections to the portrayal of Gnosticism in the anti-Gnostic writings of the church fathers, it is increasingly evident that the fathers did not fabricate their opponents’ views; what distortion there is comes from selection, not from invention. It is still legitimate to use materials from the writings of the fathers to characterize Gnosticism.”50

It is highly improbable that all of the Gnostic materials could have been systematically confiscated or destroyed by the early church. Dunn finds it unlikely that the reason we have no unambiguously first century documents from Christian Gnostics is because the early church eradicated them. He believes it more likely that we have none because there were none.51 But by archaeological virtue of Nag Hammadi, we now do have many primary source Gnostic documents available for detailed inspection. Yet they do not receive superior marks as historical documents about Jesus. In a review of The Gnostic Gospels, noted biblical scholar Raymond Brown affirmed that from the Nag Hammadi “works we learn not a single verifiable new fact about the historical Jesus’ ministry, and only a few new sayings that might possibly have been his.”52

Another factor foreign to the interests of Gnostic apologists is the proposition that Gnosticism expired largely because it lacked life from the beginning. F. F. Bruce notes that “Gnosticism was too much bound up with a popular but passing phase of thought to have the survival power of apostolic Christianity.”53

Exactly why did apostolic Christianity survive and thrive? Robert Speer pulls no theological punches when he proclaims that “Christianity lived because it was true to the truth. Through all the centuries it has never been able to live otherwise. It can not live otherwise today.”54

NOTES

1 Herbert Butterfield, Christianity and History (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1950), 119.

2 Harold W. Attridge and George W. MacRae, “Introduction: The Gospel of Truth,” in James M. Robinson, ed., The Nag Hammadi Library (San Francisco: Harper and Row, 1988), 38.

3 Wesley W. Isenberg, “Introduction: The Gospel of Philip,” Ibid., 139.

4 Joseph Fitzmyer, “The Gnostic Gospels According to Pagels,” America, 16 Feb. 1980, 123.

5 F. F. Bruce, Jesus and Christian Origins Outside the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1974), 154.

6 Robinson, 434.

7 Ibid., 435.

8 Robinson, “Introduction,” 2.

9 Ibid., 3.

10 Ibid., 2.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 See Ray Summers, The Secret Sayings of the Living Jesus (Waco, TX: Word Books, 1968), 14.

14 Michael Grosso, “Testing the Images of God,” Gnosis, Winter 1989, 43.

15 Wesley W. Isenberg, “Introduction: The Gospel of Philip,” in Robinson, 141.

16 Craig Blomberg, The Historical Reliability of the Gospels (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 1987), 208.

17 Ibid.

18 See Stephan Hoeller, “Valentinus: A Gnostic for All Seasons,” Gnosis, Fall/Winter 1985, 25.

19 Ibid., 38.

20 Bentley Layton, The Gnostic Scriptures (Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Co., 1987), 251.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid.

23 C. M. Tuckett, “Synoptic Tradition in the Gospel of Truth and the Testimony of Truth,” Journal of Theological Studies 35 (1984):145.

24 Blomberg, 213-14.

25 Andrew K. Hembold, The Nag Hammadi Texts and the Bible (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1967), 88-89.

26 Christopher Tuckett, “Synoptic Tradition in Some Nag Hammadi and Related Texts,” Vigiliae Christiane 36 (July 1982):184.

27 Robinson, 32.

28 Ibid.

29 Francis E. Williams, “Introduction: The Apocryphon of James,” in Robinson, 30.

30 Blomberg, 213.

31 Robert Winterhalter, The Fifth Gospel (San Francisco: Harper and Row, 1988), 13.

32 Robinson, 131; See Bruce, Jesus and Christian Origins, 130-31.

33 Robinson, 131.

34 Ibid., 132.

35 Layton, 377.

36 See Craig L. Blomberg, “Tradition and Redaction in the Parables of the Gospel of Thomas,” Gospel Perspectives 5: 177-205.

37 Blomberg, Historical Reliability, 211.

38 Ibid., 212.

39 See Joseph A. Fitzmyer, “The Oxyrhynchus Logoie of Jesus and the Coptic Gospel According to Thomas,” in Joseph Fitzmyer, Essays on the Semitic Background of the New Testament (Missoula, MT: Scholars Press, 1974), 355-433.

40 James D. G. Dunn, The Evidence for Jesus (Philadelphia, PA: Westminster Press, 1985), 101.

41 Ibid.

42 Ibid., 102.

43 Ibid.

44 Marvin W. Meyer, “Jesus in the Nag Hammadi Library,” Reformed Journal (June 1979):15.

45 Winterhalter, 4.

46 Robert M. Grant with David Noel Freedman, The Secret Sayings of Jesus (Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, Inc., 1960), 115.

47 Fitzmyer, “The Gnostic Gospels According to Pagels,” 123.

48 James Dunn, Unity and Diversity in the New Testament (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1977), 287-88.

49 Ibid., 288; see also Blomberg, Historical Reliability, 219.

50 Patrick Henry, New Directions (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1977), 282.

51 Dunn, The Evidence, 97-98.

52 Raymond E. Brown, “The Gnostic Gospels,” The New York Times Book Review, 20 Jan. 1980, 3.

53 F. F. Bruce, The Canon of Scripture (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 1988), 278.

54 Robert E. Speer, The Finality of Jesus Christ (Westwood, NJ: Fleming H. Revell Company, 1933), 108.

| GLOSSARY |

| aeons: Emanations of Being from the unknowable, ultimate metaphysical principle or pleroma (see pleroma). |

| Nag Hammadi collection: A group of ancient documents dating from approximately A.D. 350, predominantly Gnostic in character, which were discovered near Nag Hammadi, Egypt in 1945. |

| pleroma: The Greek word for “fulness” used by the Gnostics to mean the highest principle of Being where dwells the unknown and unknowable God. Used in the New Testament to refer to “fullness in Christ” (Col. 2:10) who is the known revelation of God in the flesh. |

| pseudepigrapha: Ancient documents which falsely claim authorship by noteworthy individuals for the sake of credibility; for instance, the Gospel of Thomas. |

| syncretism: The teaching that various religious truth-claims can be synthesized into one basic, underlying unity. |

| Valentinus: Influential early Gnostic of the Second Century A.D. who may have authorized the Nag Hammadi document, the Gospel of Truth. |